New Jersey State Rail Plan the New Jersey Railroad System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

Atlantic City Line Master File

Purchasing Tickets Ticket Prices know before you go Station location and parking information can be found at njtransit.com tickets your way how much depends on how frequently & how far Accessible Station Bus Route Community Shuttle Travel Information Before starting your trip, Ticket Vending Machines are available at all stations. visit njtransit.com for updated service information LINE Weekend, Holiday and access to DepartureVision which provides your train on-board trains track and status. You can also sign up for free My Transit Train personnel can accept cash avoid Atlantic City Philadelphia and Special Service alerts to receive up-to-the-moment delay information only (no bills over $20). All tickets the $5 on your cell phone or web-enabled mobile device, or purchased on-board trains (except one-way one-way weekly monthly one-way one-way weekly monthly those purchased by senior citizens surcharge STATIONS reduced reduced Philadelphia Information via email. To learn about other methods we use to International PHILADELPHIA communicate with you, visit njtransit.com/InTheKnow. and passengers with disabilities) are buy before Atlantic City … … … … $10.75 4.90 94.50 310.00 30TH STREET STATION subject to an additional $5 charge. Airport you board Absecon $1.50 $0.75 $13.50 $44.00 10.25 4.65 86.00 282.00 414, 417, 555 Please note the following: Personal Items Keep aisleways clear of Please buy your ticket(s) before tic City ANTIC CITY obstructions at all times. Store larger items in boarding the train to save $5. There is Egg Harbor City 3.50 1.60 30.00 97.00 10.25 4.65 86.00 282.00 L the overhead racks or under the seats. -

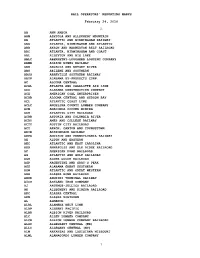

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

The Millennial Revolution in Electrical Transmission

I N S I D E T H E M I N D S Complying with Energy and Natural Resources Regulations Leading Lawyers on US Energy Markets and Regulators’ Attempts to Provide Oversight 2014 Thomson Reuters/Aspatore All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the U.S. Copyright Act, without prior written permission of the publisher. This book is printed on acid free paper. Material in this book is for educational purposes only. This book is sold with the understanding that neither any of the authors nor the publisher is engaged in rendering legal, accounting, investment, or any other professional service. Neither the publisher nor the authors assume any liability for any errors or omissions or for how this book or its contents are used or interpreted or for any consequences resulting directly or indirectly from the use of this book. For legal advice or any other, please consult your personal lawyer or the appropriate professional. The views expressed by the individuals in this book (or the individuals on the cover) do not necessarily reflect the views shared by the companies they are employed by (or the companies mentioned in this book). The employment status and affiliations of authors with the companies referenced are subject to change. For customer service inquiries, please e-mail [email protected]. If you are interested in purchasing the book this chapter was originally included in, please visit www.west.thomson.com. -

Rio Grande Station Cape May County, NJ Name of Property County and State 5

NPS Form 10-900 JOYf* 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) !EO 7 RECE!\ United States Department of the Interior National Park Service n m National Register of Historic Places Registration Form ii:-:r " HONAL PARK" -TIO.N OFFICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form I0-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property________________________________________________ historic name R'Q Grande Station____________________________________ other names/site number Historic Cold Spring Village Station______________________ 2. Location street & number 720 Route 9 D not for publication city or town Lower Township D vicinity state New Jersey_______ code NJ county Cape May_______ code 009 zip code J5§204 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Q nomination G request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets D doss not meet the National Register criteria. -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Building a Transit-Friendly Community

BUILDING A T R A N S I T - F R I E N D LY C O M M U N I T Y P L AC E AC C E SS D E V E LO P M E N T PA R K I N G PA R T N E R S H I P S I . W H AT IS A TRANSIT- F R I E N D LY COMMUNITY? TA B L E 0 8 II. O F H OW TO START DOW N KEY FINDINGS AND THE TRANSIT-FRIENDLY C O N T E N T S L E SSONS LEARNED T R AC K 0 3 1 1 34 P L AC E I I I . L E SSONS 1- 4 GETTING STA R T E D I N T R O D U CT I O N A P P E N D I X 0 7 1 7 34 36 AC C E SS THE PROGRAM L E SSONS 5-7 THE PROCESS COMMUNITIES SELECT E D 2 1 35 3 7 D E V E LOPMENT L E SSONS 8-13 MAKING IT HAPPEN S TATIONS SELECT E D 2 7 3 9 PA R K I N G L E SSONS 14-18 PROGRAM EVA LU ATO R 3 1 4 0 PA R T N E R S H I P L E SSONS 19-22 PROGRAM PA R T N E R S 0 3 I N T R O D U CT I O N A c ro ss the nation, A m e r i cans are re d i s covering the place s the auto m o b i le age left behind. -

Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options

Advocacy Sustainability Partnerships Fort Washington Office Park Transportation Demand Management Plan Geospatial Analysis: Commuters Access to Transportation Options Prepared by GVF GVF July 2017 Contents Executive Summary and Key Findings ........................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Sources ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 ArcMap Geocoding and Data Analysis .................................................................................................. 6 Travel Times Analysis ............................................................................................................................ 7 Data Collection .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Employee Commuter Survey Results ................................................................................................ 7 2. Office Park Companies Outreach Results ......................................................................................... 7 3. Office Park -

No Action Alternative Report

No Action Alternative Report April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 2. NEC FUTURE Background ............................................................................................................................ 2 3. Approach to No Action Alternative.............................................................................................................. 4 3.1 METHODOLOGY FOR SELECTING NO ACTION ALTERNATIVE PROJECTS .................................................................................... 4 3.2 DISINVESTMENT SCENARIO ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. No Action Alternative ................................................................................................................................... 6 4.1 TRAIN SERVICE ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 4.2 NO ACTION ALTERNATIVE RAIL PROJECTS ............................................................................................................................... 9 4.2.1 Funded Projects or Projects with Approved Funding Plans (Category 1) ............................................................. 9 4.2.2 Funded or Unfunded Mandates (Category 2) ....................................................................................................... -

BULLETIN - FEBRUARY, 2010 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - FEBRUARY, 2010 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 53, No. 2 February, 2010 The Bulletin NOR’EASTER HITS EASTERN SEABOARD Published by the New Although the “official” start of winter was not boarded a following train that got them to York Division, Electric until Monday, December 21, 2009, the first Ronkonkoma at 8:45 when they were sched- Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box major winter storm, a Nor’easter, traveled up uled to arrive at 4:14 AM. Thanks to member 3001, New York, New the eastern seaboard, arriving in the metro- Larry Kiss, who filled in some details. York 10008-3001. politan area Saturday afternoon, December Later that day, at 8:45 PM, service was sus- 19. It continued through Sunday, December pended between Ronkonkoma and Green- 20, dumping up to 26” of snow in eastern port and there were scattered delays on the For general inquiries, contact us at nydiv@ Long Island. Portions of New Jersey also Port Jefferson, Babylon and Montauk erausa.org or by phone received significant amounts. In New York Branches. Traffic reports in the following days at (212) 986-4482 (voice City, approximately 11 inches were recorded also told of minor delays. mail available). The in Central Park, 13.2 inches in Sheepshead Our Editor-in-Chief, Bernie Linder, saw on a Division’s website is www.erausa.org/ Bay, six inches in the Bronx, and only a trace news report on Channel 7 that the lead car of nydiv.html. in Poughkeepsie. Many areas received re- each LIRR MU train, and probably also the cord amounts of snow. -

Amtrak Station Development

REAL ESTATE TRANSACTION ADVISORY SERVICES • Improving Performance and Value of Amtrak-owned Assets AMTRAK STATION DEVELOPMENT New York Penn Station| Moynihan Train Hall| Philadelphia 30th Street Station Baltimore Penn Station| Washington Union Station | Chicago Union Station • Pre-Proposal WebEx | August 5, 2016 Rina Cutler –1 Sr. Director, Major Station Planning and Development AASHTO Conference| September 11, 2018 SUSTAINABLE FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE 1 AMTRAK MAJOR STATIONS Amtrak is actively improving & redeveloping five stations: Chicago Union Station, NY Penn Station, Baltimore Penn Station, Washington Union Station and 30th Street Station in Philadelphia. NEW YORK PENN STATION WASHINGTON UNION STATION #1 busiest Amtrak Station #2 busiest Amtrak Station NEW YORK PENN STATION ● 10.3 million passengers ● 5.1 million passengers PHILADELPHIA 30TH ● $1 billion ticket revenue ● $576 million ticket revenue CHICAGO BALTIMORE PENN STATION STREET STATION UNION STATION ● 1,055,000 SF of building area ● 1,268,000 SF of building area WASHINGTON UNION STATION ● 31.0 acres of land PHILADELPHIA 30TH STREET STATION CHICAGO UNION STATION BALTIMORE PENN STATION #3 busiest Amtrak Station #4 busiest Amtrak Station #8 busiest Amtrak Station ● 4.3 million passengers ● 3.4 million passengers ● 1.0 million passengers ● $306 million revenue ● $205 million ticket revenue ● $95 million ticket revenue ● 1,140,200 SF of building area ● 1,329,000 SF of building area ● 91,000 SF of building area FY 2017 Ridership and Ridership Revenue 2 MAJOR STATION PROJECT CHARACTERISTICS -

3.5: Freight Movement

3.5 Freight Movement 3.5 Freight Movement A. INTRODUCTION This section describes the characteristics of the existing rail freight services and railroad operators in the project area. Also addressed is the relationship between those services and Build Alternative long-term operations. The study area contains several rail freight lines and yards that play key roles in the movement of goods to and from the Port of New York and New Jersey, the largest port on the east coast, as well as in the movement of goods vital to businesses and residents in multiple states. However, no long-term freight movement impacts are anticipated with the Build Alternative, and no mitigation measures will be required. B. SERVICE TYPES The following freight rail services are offered in the project area: • Containerized or “inter-modal” consists primarily of containers or Example of Doublestack Train with Maritime truck trailers moved on rail cars. Containers Intermodal rail traffic is considered the fastest growing rail freight market, and is anticipated to grow in the region between 3.9 and 5.6 percent annually through 2030, based on the NJTPA Freight System Performance Study (see Table 3.5-1). • Carload traffic consists of products that are typically moved in boxcars, hopper cars, tank cars, and special lumber cars over a long distance by rail, and then either transported directly by rail or Example of Carload Rail Traffic shifted to truck for delivery to more local customers. The characteristics of these commodities (e.g., bulk, heavy or over- dimensional) make rail the preferred option for long-distance movement.