Response from Talktalk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript of Hearing (Day 3)

1 Wednesday, 5 October 2016 2 (10.30 am) 3 THE CHAIRMAN: Good morning, Mr Beard. 4 MR BEARD: Mr Chairman, members of the tribunal, we are 5 moving on to factual evidence, and the first witness to 6 be called is Mr John Petter. 7 MR JOHN RICHARD MARTIN PETTER (sworn) 8 Examination-in-chief by MR BEARD 9 MR BEARD: Mr Petter, good morning. First of all, you 10 should have in front of you a set of bundles -- ah, they 11 are behind. That is a good start. 12 Those bundles, just for the tribunal's information, 13 should contain material that is confidential to BT. It 14 is obviously not material that is confidential to other 15 parties. So some of the redactions will be different 16 from the material you have before you. 17 Could you be passed bundle N1, or core 1, depending 18 on how it is labelled. If you could turn to tab B, 19 there is a document that, on the first page, is said to 20 be a witness statement of Mr John Richard Martin Petter. 21 If you turn to the back of that document, do you have 22 a signature page? 23 A. Yes, I do, page 79. 24 Q. Is this your witness statement? 25 A. That's right, it is, yes. 1 1 Q. Just for the tribunal's note, the versions you have 2 won't have a signature on the back page because, when 3 the confidentiality marking was done, it was done on an 4 electronic version? 5 THE CHAIRMAN: You will be pleased to know that I do have 6 a signature page. -

Talktalk Telecom Group Limited Annual Report 2021 1 STRATEGIC REPORT Our Business Model

TalkTalk Telecom Group Limited 2021 Annual Report 2021 Annual Limited Group Telecom TalkTalk 2021 ANNUAL REPORT TalkTalk Telecom Group Limited (formerly TalkTalk Telecom Group PLC) At a glance Contents Strategic report IFC At a glance 2 Our business model 4 Our strategy 6 Key performance indicators 8 Business and financial review 13 Principal risks and uncertainties HQ 18 Section 172 Salford, Greater 24 Regulatory environment Manchester 26 Corporate social responsibility Corporate governance 30 Corporate governance 35 Audit Committee report 38 Directors’ remuneration report 53 Directors’ report 55 Directors’ responsibility statement 47,300 Financial statements Over 3,000 high-speed unbundled 56 Independent auditor’s report Ethernet 66 Consolidated income statement exchanges 67 Consolidated balance sheet connections 68 Consolidated cash flow statement 69 Consolidated statement of changes in equity 70 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 108 Company balance sheet 109 Company cash flow statement 110 Company statement of changes in equity 111 Notes to the Company financial statements Other information UK’s 116 Five year record (unaudited) 96% largest 117 Alternative performance measures population wholesale 118 Glossary coverage broadband 120 Registered office 120 Advisers provider Over 957 million GB average 4 million customer broadband downloads per customers month Stay up to date at www.talktalkgroup.com 2,019 2.8 million employees FTTC and FTTP (as at 28 customers February 2021) WHO WE ARE TalkTalk is the UK’s leading value for money connectivity provider. We believe that simple, affordable, reliable and fair connectivity should be available to everyone. Since entering the market in the early 2000s, we have a proud history as an innovative challenger brand ensuring customers benefit from more choice, affordable prices and better services. -

Annex 2: Providers Required to Respond (Red Indicates Those Who Did Not Respond Within the Required Timeframe)

Video on demand access services report 2016 Annex 2: Providers required to respond (red indicates those who did not respond within the required timeframe) Provider Service(s) AETN UK A&E Networks UK Channel 4 Television Corp All4 Amazon Instant Video Amazon Instant Video AMC Networks Programme AMC Channel Services Ltd AMC Networks International AMC/MGM/Extreme Sports Channels Broadcasting Ltd AXN Northern Europe Ltd ANIMAX (Germany) Arsenal Broadband Ltd Arsenal Player Tinizine Ltd Azoomee Barcroft TV (Barcroft Media) Barcroft TV Bay TV Liverpool Ltd Bay TV Liverpool BBC Worldwide Ltd BBC Worldwide British Film Institute BFI Player Blinkbox Entertainment Ltd BlinkBox British Sign Language Broadcasting BSL Zone Player Trust BT PLC BT TV (BT Vision, BT Sport) Cambridge TV Productions Ltd Cambridge TV Turner Broadcasting System Cartoon Network, Boomerang, Cartoonito, CNN, Europe Ltd Adult Swim, TNT, Boing, TCM Cinema CBS AMC Networks EMEA CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership CBS Europe CBS AMC Networks UK CBS Reality, CBS Drama, CBS Action, Channels Partnership Horror Channel Estuary TV CIC Ltd Channel 7 Chelsea Football Club Chelsea TV Online LocalBuzz Media Networks chizwickbuzz.net Chrominance Television Chrominance Television Cirkus Ltd Cirkus Classical TV Ltd Classical TV Paramount UK Partnership Comedy Central Community Channel Community Channel Curzon Cinemas Ltd Curzon Home Cinema Channel 5 Broadcasting Ltd Demand5 Digitaltheatre.com Ltd www.digitaltheatre.com Discovery Corporate Services Discovery Services Play -

Analysys Mason Document

Sky launches a mobile service in the UK in anticipation of increased competition in convergence December 2016 Heenu Nihalani and Kerem Arsal Sky is the newest entrant to the UK mobile market, and the forthcoming launch of its ‘Sky Mobile’ service brings an alternative fixed–mobile proposition to a relatively nascent convergence market. As a mobile virtual network operator (MVNO), it will use O2’s network, and offer 12-month contracts in loose bundles to its fixed subscribers, as well as separately to non-subscribers at a higher price point. Sky reports that over 46 000 people have pre-registered for Sky Mobile, which will be launched in mid-December. This article examines Sky Mobile’s pricing and positioning in more detail, and discusses the effects that this service may have on the UK’s mobile and FMC markets. Sky is clearly targeting its mobile proposition at its current customer base Sky is entering the market with relatively cautious pricing, without aggressive discounting, and with continued focus on premium services. It is a convincing offer for its fixed broadband subscribers, but less so for non- subscribers. The service is positioned to compete in a marketplace increasingly dominated by converged offers following BT’s acquisition of EE in August 2016. Pricing for Sky’s fixed customers is competitive. Prices are tiered around data allowances: GBP10 per month for 1GB, GBP15 for 3GB, and GBP20 for 5GB; each comes with unlimited voice and SMS. The pricing closely matches similar plans from Virgin Media and Vodafone, while BT’s pricing is slightly lower for its FMC bundle subscribers. -

TV Viewing in the Internet Age Television As Its Content and Would Transform There Are Important Regional Variations Television Into an Art Form

TV viewing in the internet age television as its content and would transform There are important regional variations television into an art form. Some internet too. Put simply, the further away you live from BARB’s study of UK TV evangelists disagree and prefer to proclaim London, the less likely you are to timeshift viewing habits shows 87% the death of television – in particular, linear your viewing. Work–life balance issues have of all viewing is still live at television. This isn’t a new assertion by media to be at play: those low timeshift viewers in owners keen to attract television advertising Ulster, Wales, Scotland and the Borders are the point of broadcast, with budgets, although the voices sometimes seem probably enjoying all the benefits of living other uses for the TV screen louder than ever. away from the cities. The biggest timeshifters BARB is a joint industry currency that are Londoners and those in the South and representing on average is owned by the television and advertising South-East, many of whom spend long hours only 40 minutes per day. community in the UK. For 35 years we have at work sandwiched between soul-destroying been providing impartial evidence on how long commutes. Netflix and Amazon Video people watch television and are well are growing but are placed to investigate whether the complementary to linear TV alleged malaise is real or perhaps just FIGURE 1: TIMESHIFTING ANALYSIS wishful thinking. There are several Percentage timeshift viewing, 2015 and online viewing is still claims that are used to fan the flames. -

Your Youview User Guide

A brighter home for everyone Your YouView user guide 7 of the most popular Sky entertainment channels 7 day catch-up The best players on your TV Sky Sports and Sky Movies with a one month commitment Rent the latest blockbusters Dip in and out of What’s inside? Sky Sports and Sky Movies Main features 5-7 one month at a time YouView Guide 8-13 Browse and search programmes in the YouView Guide 8 Record 10 Extra channels 13 On Demand 14-19 Catch up on your TV 14 The TalkTalk Player 16 Renting films and adding Boosts 18 Your TalkTalk PIN 19 More information 21-27 Parental controls 21 5 channels for £30 a month 11 channels for £15 a month Now included with our Settings 22 Channels 501-505 Channels 530 -540 Sky Movies Boost FAQ’s 24 Troubleshooting 25 To add instantly go to the channel and press OK talktalk.co.uk/tvboost Quick connection 27 *You’ll need to have a minimum broadband speed of 5Mb to add TV Boosts. All information and prices in this guide are correct at time of going to print and subject to change. Get the most from your YouView box Enjoy all this: Main Features Access all your favourite Freeview channels Use your TalkTalk PIN to watch more -WTVTfV[#gcYeb`f[X You’ll need a working TV aerial to get your Freeview Sign up to our great value Boosts for a month at a YouView Guide channels. Your YouView box will automatically tune time – perfect for the school holidays or the sports -bYf[X`b fcbcg_Te^ in to the standard channels including some in HD. -

Talktalk Response

Review of the pay TV wholesale must-offer obligation TalkTalk initial submission Non-confidential version March 2015 1 Summary 1.1 This document is TalkTalk's response to Ofcom's consultation paper, dated 19 December 2014, on its ongoing review of the pay TV wholesale must offer ('WMO') obligation. 1.2 TalkTalk welcomes Ofcom's review of the WMO. This remedy was imposed on Sky in relation to Sky Sports 1 and 2 in 2010, and has been the subject of continual litigation and appeals since then; the appeal against the initial decision remains extant at the CAT. Nearly five years after the remedy was initially imposed, the pay TV market has changed considerably, both with the emergence of new pay TV platform operators (notably TalkTalk's TV platform) and changes in the line up of premium sports channel providers, particularly due to BT's acquisition of Premier League ('PL') and UEFA Champions League ('UCL') rights. It is vital that Ofcom reviews its WMO obligation regularly, to reflect changing circumstances and ensure that it remains effective in protecting consumers' interests. 1.3 Although we welcome the review, in its current proposals Ofcom has reached the incorrect conclusion that BT should not be subject to a WMO obligation. This incorrect conclusion has stemmed from several errors made by Ofcom in its consultation paper: • Ofcom has underweighted the importance of competitions other than the Premier League ('PL') relative to the PL itself. In reality, at least the Champions League ('UCL') has the same degree of importance to viewers. [✂]. • In determining whether to impose WMO obligations in future, Ofcom has only considered historic market shares rather than the more relevant forward looking shares. -

Plustv-Userguide-New.Pdf

Dip in and out of Sky Sports What’s inside? Main features 5-7 * and Sky Movies One month at YouView Guide 8-13 a time Browse and search programmes in the YouView Guide 8 Record 10 Extra channels 13 On Demand 14-19 Catch up on your TV 14 The TalkTalk Player 16 More information 21-27 Parental controls 21 Settings 22 FAQs 24 Over 1000 films on demand 6 channels for for £15 a month £30 a month Troubleshooting 25 Quick connection 27 Explore Boosts in the TalkTalk Player talktalk.co.uk/tvboost 2Front Cover: The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 2: © 2015 Lions Gate Films Inc. All Rights Reserved. Powerpuff Girls: ™ & © 2016 Cartoon Network. All Rights Reserved All information and prices in this guide are correct at time of going to print and subject to change. 3 Jurassic World: © 2015 Universal Studios and Amblin Entertainment, Inc. All Rights Reserved. *You’ll need to have a minimum broadband speed of 5Mb to add TV Boosts and receive Sky channels. A little box that does really big things More entertainment than you can shake a remote at Main Features 7 day catch-up from Watch all your favourite channels Give your TV a Boost the YouView Guide First of all, just check that your TV aerial is working properly. Your Our flexible TV Boosts let you dip in and out of Boosts for just a month YouView+ box will automatically tune in to your standard channels at a time. School holidays? Add the Kids’ Boost. Just want to watch 6 popular Sky (including some in HD). -

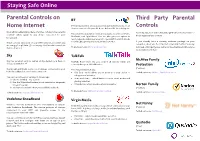

Third Party Parental Controls

Staying Safe Online Parental Controls on BT Third Party Parental BT Parental Control allows you to manage internet access on all Controls Home Internet devices connected to your BT Home Hub and BT Wi-Fi hotspots. Most UK Broadband providers offer free ‘whole-home parental This service is available for free and includes an option of Strict, You may decide to use a dedicated parental control solution to controls’ which apply to any device connected to your Moderate and Light filters. You are also given an option to block inappropriate content. broadband. restrict specific websites and set a Homework Time which blocks If you already have a security software package on your These controls only work on your Wi-Fi network, not when you social media, gaming and homework cheat sites. computer, check whether it includes Parental Control. You may are using 3G or 4G data. (See next page for Parental controls on mobile devices.) To find out more: BT Parental Controls not need a third party one. Some are free, but most will cost you an annual subscription. Sky TalkTalk McAfee Family Sky has parental controls turned on by default, you have to TalkTalk Home Safe lets you control all devices which are choose to switch it off. connected to your TalkTalk router. Protection (Paid for) Sky Broadband Shield works on all devices connected to your The free package includes; home broadband. It comes at no extra cost. Kids Safe - which allows you to block all or your choice of To find out more: McAfee Family Protection categories of websites. -

The Consequences of Privatising Channel 4

The Consequences of Privatising Channel 4 The Consequences of Privatising Channel 4 Patrick Barwise and Gillian Brooks 4 May 2016 A report commissioned and funded by Channel 4. Patrick Barwise is emeritus professor of management and marketing, London Business School and visiting senior fellow in media and communications, London School of Economics. Gillian Brooks is post-doctoral research fellow, Oxford University Centre for Corporate Reputation, Saïd Business School and tutorial fellow in management studies, St Hugh’s College, Oxford. 1 The Consequences of Privatising Channel 4 Contents Short Summary 3 Executive Summary 4 1. Aims, Issues and Scope 10 1.1 Aims and Key Issues 10 1.2 Report Structure 15 2. C4’s Remit, Culture, Role and Contribution 17 2.1 C4’s Remit, Culture and Role 17 2.2 Contribution to UK Content Investment and Independent Production 22 2.3 Broader Economic and Social Contributions 24 3. Base Case: No Privatisation 30 3.1 Base Case Assumptions 30 3.2 Revenue and Content Projections 2014-25 31 3.3 The Sustainability of the Remit 32 4. The Investment Case for a Potential Buyer 39 4.1 Who Might Buy C4? 39 4.2 Three Potential Strategies 40 4.3 Non-Programming Cost Savings 41 4.4 Revenue Synergies 44 4.5 ‘Soft’ Synergies 44 4.6 The Total Value of Non-programming Cost Savings and Synergies 45 4.7 Getting More ‘Bang for the Buck’ from C4’s Content Budget 45 4.8 CommsCorp as the Buyer 50 5. The Impact of Privatisation 54 5.1 Impact on UK Content Investment and Independent Production 54 5.2 How Would a Different Buyer Strategy Affect This? 56 5.3 Impact on the Wider UK Economy and Society 61 6. -

Changes to BBC Iplayer: Competition Assessment

CHANGES TO BBC IPLAYER Competition assessment April 2019 Clive Kenny [email protected] Frontier Economics Ltd is a member of the Frontier Economics network, which consists of two separate companies based in Europe (Frontier Economics Ltd) and Australia (Frontier Economics Pty Ltd). Both companies are independently owned, and legal commitments entered into by one company do not impose any obligations on the other company in the network. All views expressed in this document are the views of Frontier Economics Ltd. CHANGES TO BBC IPLAYER CONTENTS Executive Summary 5 1 Introduction 18 1.1 Structure of this report 18 2 Framework for assessing the impact of the BBC iPlayer changes on competition 20 2.1 Introduction 20 2.2 Regulatory framework to assess changes to the BBC’s services 20 2.3 Analytical framework for the assessment of crowding out 24 2.4 Analytical framework for the assessment of scope for harm to competition elsewhere in the supply chain 28 3 The competitive context for the proposed changes to BBC iPlayer 30 3.1 The audio-visual sector is characterised by constant innovation 30 3.2 VoD competes with linear broadcasters, as well as newer audio-visual suppliers 31 3.3 Technological advances have led to convergence between different forms of content 33 3.4 Entrant broadcasters have put pressure on broadcasters to compete and innovate 33 3.5 Conclusion on sector wide trends 35 4 Suppliers affected by the changes to BBC iPlayer 37 4.1 Introduction 37 4.2 The BBC iPlayer’s role in the TV value chain 37 4.3 Identifying -

Talktalk Telecom Group PLC Annual Report 2016 Strategic Report

Annual Report 2016 Group PLC Telecom TalkTalk TalkTalk Telecom Group PLC | Annual Report 2016 2016 TalkTalk is the UK’s leading value for money quad play provider. Our mission is to deliver affordable, reliable, simple, and fair telecoms services for everyone. Contents Strategic report Corporate governance Financial statements At a glance ..............................................................................03 Board of Directors Independent auditor’s report .................................... 60 Chairman’s statement ................................................... 04 and Executive Committee ................................. 28 Consolidated income statement .............................65 Operational and financial highlights ................. 04 Corporate governance .................................................. 30 Consolidated statement Chief Executive Officer’s review ...............................05 Audit Committee .............................................................. 34 of comprehensive income ...........................................66 Chief Financial Officer’s statement ....................... 08 Directors’ Remuneration Report .............................. 37 Consolidated balance sheet .......................................67 Business model and strategy .......................................12 Other statutory information .......................................56 Consolidated cash flow statement .........................68 Market opportunity ������������������������������������������������������������15