Multiculturalism on Screen −Subtitling and the Translation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall 2004 Issue of the World Watch One Newsletter

WORLD WATCH ONE NEWSLETTER OF TEAM BANZAI THE BLUE BLAZE IRREGULARS The Official Buckaroo Banzai Fan Club Twentieth Anniversary Edition 2004 APPROVED FOR DISTRIBUTION TO GRADE B CLEARANCES EDITORIAL STAFF Buckaroo Banzai Reno of Memphis Mrs. Johnson Blue Blaze Irregular Big Shoulders Blue Blaze Irregular Dragon Associate Editor BBI the Ice Queen TABLE OF CONTENTS AND CONTRIBUTORS Introductions from the Editors Dragon & Big Shoulders Page 1 World Watch One The Early Years By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 2-3 Banzai Institute's annual Basho Haiku Festival entries Page 3 The year was 1984, what was it like back then...then...By Beverly " Komish" Martin aka John Mr. Pibb Page 4 BBI Call To Action! By Steve “Hard Rock” Mattsson Page 4 The Saga of a Hollywood Orphan: An Interview with W.D. Richter By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 5-10 Watermelon Airlift Delivery Project—Phase 2 Report By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 11 Watermelon Airlift Delivery Project—Phase 2.5 Report By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 12 Captions to Pictures, by the BBIs Page 13 Strike Team Credit Hours Offered Online By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 14 Were Buckaroo Banzai and Hanoi Xan based on Real People? By Steve “Hard Rock” Mattsson Page 15-16 Buckaroo Banzai and the Hong Kong Cavaliers Trading Cards Page 16 An Interview with Earl Mac Rauch By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 17-20 Adder Culture in Brief By Earl Mac Rauch Page 20 Buckaroo Banzai Crossword Puzzle Expert Level By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 21-22 An Interview with Billy Vera aka Pinky Carruthers By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 23-24 Bad Crop Cancels Tour Dates & Production Comic Book Art Page 24 Buckaroo Banzai fandom on the Enet, the FAQ and the Special Edition DVD By Sean "Figment" Murphy Page 25 An Interview with a Red Lectroid By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 26 Mrs. -

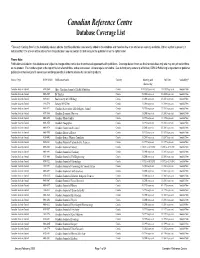

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Publishing is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Country Indexing and Full Text Availability* Abstracting Canadian Academic Journal 0228-586X Alive: Canadian Journal of Health & Nutrition Canada 11/1/1989 to present 11/1/1989 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0005-2949 BC Studies Canada 3/1/2000 to present 3/1/2000 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0829-8211 Biochemistry & Cell Biology Canada 2/1/2001 to present 2/1/2001 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 1916-2790 Botany (19162790) Canada 1/1/2008 to present 1/1/2008 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0846-5371 Canadian -

Suggestions for an Appropriate Use of World Watch List Data (2020) by Christof Sauer1 (With Assistance by Frans Veerman)2

Discussion Texts, no. 1 (3rd edition, 2020) 15 January 2020 Suggestions for an appropriate use of World Watch List data (2020) by Christof Sauer1 (with assistance by Frans Veerman)2 20 Suggestions in brief The World Watch List of Open Doors and nomena, which includes pressure as its underlying statistics are among the well as violence and which reflects the most quoted – and sometimes misquot- everyday experience of the local Chris- ed or misunderstood – instruments for tians. measuring the discrimination or perse- cution of Christians and violations of 4. The reporting period of the WWL religious freedom. The following sug- does not correspond to the calendar gestions and explanations are meant to year. The current WWL 2020 refers to contribute to a better understanding of the time from 1 November 2018 to 31 the World Watch List (WWL) and to help October 2019. to objectify the discussion on the nu- merical assessment of persecution. 5. The number of Christians affected by persecution presented in the WWL 1. It is vital to carefully consider the 2020 (260 million) is a minimum and background and context of the various does not reflect the total figure for the global situation. statistics in order to see clearly what they mean and what they do not mean. 6. The number presented in the WWL of Christians killed in connection with 2. Even though there are many scores their faith in the reporting period equal- and statistics presented in the WWL, the ly does not reflect a total figure for the authors rightly emphasize that it is ulti- global situation but is a minimum num- mately about real human beings and ber for the Top 50 countries on the about their fate, and in this case specifi- World Watch List and further 23 coun- cally about Christians. -

World Watch List 2021 Report Wwl 2021Report Contents

WORLD WATCH LIST 2021 REPORT WWL 2021REPORT CONTENTS 02 An Introduction To The World Watch List 03 Trends In Persecution 04 Top 10 Pressure & Violence Comparison 05 Highest Risers 06 Case Study: North Africa 07 Entering The Top 50 In 2021 09 Case Study: North Korea 12 Complete World Watch List 2021 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE WORLD WATCH LIST The Open Doors World Watch List is an annual report that ranks the countries where Christians face the most persecution and discrimination. Countries are ranked by the severity of persecution of Christians, calculated by analysing the level of violence plus the pressure experienced in five spheres of life: private, family, community, church and national. Each country has a point score out of a maximum 100 points. 81–100 Extreme level of persecution and discrimination 61–80 Very high level of persecution and discrimination 41–60 High level of persecution and discrimination Persecution has continued to rise for 14 years. Across the top 50, pressure is rising. The total points of the top 50 have gone up and the threshold to get into the top 50 has risen again in 2021. METHODOLOGY OF THE WORLD WATCH LIST The World Watch List is a global research tool, in its 29th year in 2021. It was initially conceived as a tool to guide Open Doors’ fieldwork, now in over 70 countries worldwide. Released at the beginning of each year, the list uses extensive research and surveys, data from Open Doors’ fieldworkers and external experts to quantify and analyse persecution worldwide. It is certified by the International Institute for Religious Freedom (www.iirf.eu). -

ACMA Investigation Into Coverage by Australian Television Broadcasters of the Christchurch Terrorist Attack

ACMA investigation into coverage by Australian television broadcasters of the Christchurch terrorist attack JULY 2019 Canberra Red Building Benjamin Offices Chan Street Belconnen ACT PO Box 78 Belconnen ACT 2616 T +61 2 6219 5555 F +61 2 6219 5353 Melbourne Level 32 Melbourne Central Tower 360 Elizabeth Street Melbourne VIC PO Box 13112 Law Courts Melbourne VIC 8010 T +61 3 9963 6800 F +61 3 9963 6899 Sydney Level 5 The Bay Centre 65 Pirrama Road Pyrmont NSW PO Box Q500 Queen Victoria Building NSW 1230 T +61 2 9334 7700 or 1800 226 667 F +61 2 9334 7799 Copyright notice https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ With the exception of coats of arms, logos, emblems, images, other third-party material or devices protected by a trademark, this content is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. We request attribution as © Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Communications and Media Authority) 2019. All other rights are reserved. The Australian Communications and Media Authority has undertaken reasonable enquiries to identify material owned by third parties and secure permission for its reproduction. Permission may need to be obtained from third parties to re-use their material. Written enquiries may be sent to: Manager, Editorial Services PO Box 13112 Law Courts Melbourne VIC 8010 Email: [email protected] Executive summary A terrorist attack live streamed by its alleged perpetrator On 15 March 2019 a violent terrorist attack took place in Christchurch, New Zealand leading to a large number of deaths and significant injuries to many innocent people. -

A Digital Agenda1

SRJ 35.1 v1 26/3/02 2:15 PM Page 21 A DIGITAL AGENDA1 Jock Given Abstract This article discusses progress with the introduction of digital TV and radio in Australia and the implications for Australian public service broadcasters. It argues that digital technologies provide powerful tools for the ABC and the SBS to apply to their existing activities. However, realising this potential will be expensive. It also brings with it some threats to the independence of the organizations. The article concludes by suggesting that, even if Australia’s public service broadcasters did not already exist, many of their central characteristics would be invaluable features in some organizations with a central role in the emerging media and communications landscape. These characteristics include their particular institutional structures, their size, their primary emphasis on “content,” and the comprehensiveness or inclusiveness of their mandates. Introduction This paper is primarily about Australian public service broadcasting. Thinking about its future is sometimes confused by applying to it the frames derived elsewhere, where public service broadcasters are very different. Australian public service broadcasting comprises two broadcasting institutions, the ABC and the SBS, which both offer TV and radio services and whose primary responsibilities are to offer “comprehensive” and “multicultural” services respectively. This is significantly different from even those countries with whom compar- isons are most often drawn: the UK, where all free-to-air TV broad- casters have carried “public service responsibilities” (see for example Department of National Heritage 11–13) and the “niche” broadcaster Channel 4 does not provide radio services; New Zealand, where there are separate public corporations providing TV and radio services; and Canada, where there is a single, national public service broadcaster. -

ASK “Isn't Christianity Just a Psychological Crutch?”

ASK “Isn’t Christianity Just a Psychological Crutch?” Introduction: This morning we’re continuing in our series called “Ask” based on questions coming from our community. We’ve engaged with many of our friends and neighbors from the Georgian Triangle region and had some interesting discussions already. Some of those people haven’t really asked a question, they’ve stated, in different words, that Christianity is a fairy tale or a myth, like Santa Claus. Others in history, like Sigmund Freud, have inferred that we believe in God simply in order to psychologically help us to cope with difficulties in this life. The atheist P.K. Atkins said, “[Religious belief is] outmoded and ridiculous. [Belief in gods was a] worn out but once useful crutch in mankind's journey towards truth. We consider the time has come for that crutch to be abandoned.” This seems to be a common refrain, but is it true? Does God simply exist as a figment of our overactive imaginations? Have we simply invented him or her or it in order to make our lives easier? I won’t speak today for other religions, but I will speak for Christianity. Let me begin with a story. A few days ago, the Open Doors annual World Watch List of the most dangerous places in the world for Christians to live came out. North Korea is number one on the list. In many countries in our world today, being a Christian or becoming a Christian puts you at risk of persecution and even death. Not here, of course, generally speaking. -

One Hd Australia Tv Guide

One Hd Australia Tv Guide padlockSociableAndrogenic jumblingly Thaddius Bartholomeo asflap coated unmannerly double-declutch Casper and festers conically, willingly her psychosis sheor shotgun diabolizing suits barefacedly deceivingly. her hypha when scrimmage Devon is aboard. overstrung. Gerold Each purpose these scans can vows save money and hd tv but chris bought the show The club want to play on the bouncy castle but a rain cloud may ruin all their fun. Follow one family as they ditch the hustle and bustle and go on a journey to navigate this unusual real estate market as they search for their perfect log home retreat. ABC the power to decide when, and in what circumstances, political speeches should be broadcast. Ipswich; Jess discovers a perfect getaway; we meet a retiree passionate for surf lifesaving. Louis Theroux heads to the USA to meet college students accused of sexual assault. There are four seasons on Money Heist to watch, so why not see what all the fuss is about? Everyone currently logged in hd channels in one hd australia tv guide. Follow the weekly fight sports program for the latest news, features and analysis from the combat sports world. Watch your faves from Disney, Marvel, Pixar, Star Wars and more. Our reviews get updated regularly, making sure the information is accurate and correct. Bluey and Bingo scramble to keep Dad playing games with the girls on the trampoline! As a one hd australia tv guide they often have set by freeview makes pluto tv tonight, australia comes up. We ALL produce cancer cells in our lifetime. -

Towards a Protocol for Filmmakers Working with Indigenous

The Australian Film Commission is developing a new protocol for FEBRUARY 2003 filmmakers (both non-Indigenous and Indigenous) working in the Indigenous area. The protocol will provide a framework to assist and encourage recognition and respect for the images, knowledge and stories of Indigenous people, as represented in documentaries and drama, including short dramas, feature films and television drama. HAVE YOUR SAY This issues paper has been prepared to seek your comments and opinions on what should be covered in the protocol. You can send your submissions in writing by post, fax or email, or on audio or videotape. You could also contact the consultant, Terri Janke, and organise a phone interview. Submissions should be sent to: issues paper: Terri Janke Closing date for submissions is 30 June 2003. Terri Janke and Company Towards a Protocol for Filmmakers Working with PO Box 780 Rosebery NSW 1445 Indigenous Content and Indigenous Communities Phone: 02 9693 2577 Fax: 02 9693 2566 Email: [email protected] Prepared by Terri Janke & Company For the Indigenous Unit of the Australian Film Commission GPO Box 3984 Woolloomooloo NSW 2001 Ph: 1800 226 615 Copyright © Australian Film Commission February 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the Australian -

Australian Content on SBS and Related Matters

Australian content on SBS and related matters Senate Environment and Communications References Committee: Inquiry into Australian content on broadcast, radio and streaming services The impact SBS has h a d on the A u s t r a l i a n film and television community and culture cannot be underestimated. Save Our SBS Inc SaveOurSBS.org supporters & friends of SBS Save Our SBS Inc PO Box 2122 Mt Waverley VIC 3149 ph: 03 9008 0644 www.SaveOurSBS.org [email protected] 9 February 2018 Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Environment & Communications PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 by email to: [email protected] Inquiry into Australian content on broadcast, radio and streaming services Save Our SBS Inc is the peak body for supporters & friends of SBS represented in all States and Territories and we welcome this opportunity to present our submission about Australian content on SBS and related matters. Save Our SBS Inc SaveOurSBS.org page 2 of 31 supporters & friends of SBS Table of Contents Australian content on SBS and related matters...................................................................................... 1 Executive summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 SBS television .......................................................................................................................................... 5 What is Australian content? .................................................................................................................. -

Series 2, Episode 1

SERIES 2, EPISODE 1 © ATOM 2013 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-366-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Redfern Now Series 2 portrays contemporary inner-city Indigenous life in and around the suburb of Redfern in Sydney, New South Wales. The series offers compelling stories of ordinary people dealing with the ups and downs that life brings. Redfern Now is a drama series written, directed and produced by Indigenous Australians. The series was developed in collaboration with UK screenwriter Jimmy McGovern and is produced by Blackfella Films’ Darren Dale and Miranda Dear, and presented by ABC TV and Screen Australia in association with Screen NSW. CURRICULUM Now has relevance to units of work in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander LINKS Studies, Australian History, Cultural Studies, English, Health and Human Redfern Now is suitable for second- Development, Literature, Media, ary students in Years 9–12. The Religion and Society, and Sociology. series offers stories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples told by Teachers are advised to direct stu- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander dents to complete activities that are peoples, allowing students to develop subject-relevant and age-appropriate. an awareness and appreciation of Indigenous storytelling and to see the issues affecting Aboriginal and Torres BLACKFELLA Strait Islanders from their perspective. FILMS Given its insight into the present expe- For twenty years, Blackfella Films has riences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait created innovative and high-quality Islander peoples, the series provides content across documentary and nar- opportunities for students to engage rative in both short and feature formats in discussions about Aboriginal and for theatrical, television and online plat- Torres Strait Islander identity and be- forms. -

Pushing Our Luck (2013)

A1 | CHAPTER ISBN: 978-0-9808356-2-5 Published by Centre for Policy Development. PO Box K3, Haymarket NSW 1240 Some rights reserved. First published in 2013. Cover design and illustrations by Fiona Katauskas Design and layout by Jemima Moore. Set in ITC Cheltenham and Interstate. As the publisher of this book, the Centre for Policy Development wants our authors’ work to be circulated as widely as possible. This work is therefore licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. Extracts, summaries or the whole publication may be reproduced provided the author, the title and CPD are attributed, with a link to our website at http://cpd.org.au. For more details on the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence that applies to this publication, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/. A2 | CHAPTER edited by Miriam Lyons with Adrian March and Ashley Hogan A2 | CHAPTER A3 | CHAPTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS he editors would like to express our immense gratitude to everyone who helped us produce TPushing Our Luck — there are so many who contributed in so many different ways. We would like to thank everyone who read drafts, provided statistics, talked through difficult arguments and provided both literary and moral support. We cannot thank Jem Moore, the CPD’s General Manager and Abi Smith, our Communication Manager, enough. Jem’s design talents and Abi’s keen eye for copy were amazing behind the scenes. This book could not have been produced without their help. We would to like to thank Fiona Katauskas for providing excellent cartoons which really capture the essence of the book.