A Digital Agenda1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers Cento Veljanovski CASE ASSOCIATES Current Issues June 1999 Published by the Institute of Public Affairs ©1999 by Cento Veljanovski and Institute of Public Affairs Limited. All rights reserved. First published 1999 by Institute of Public Affairs Limited (Incorporated in the ACT)␣ A.C.N.␣ 008 627 727 Head Office: Level 2, 410 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Phone: (03) 9600 4744 Fax: (03) 9602 4989 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ipa.org.au Veljanovski, Cento G. Pay TV in Australia: markets and mergers Bibliography ISBN 0 909536␣ 64␣ 3 1.␣ Competition—Australia.␣ 2.␣ Subscription television— Government policy—Australia.␣ 3.␣ Consolidation and merger of corporations—Government policy—Australia.␣ 4.␣ Trade regulation—Australia.␣ I.␣ Title.␣ (Series: Current Issues (Institute of Public Affairs (Australia))). 384.5550994 Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute of Public Affairs. Printed by Impact Print, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056 Contents Preface v The Author vi Glossary vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Pay TV Picture 9 More Choice and Diversity 9 Packaging and Pricing 10 Delivery 12 The Operators 13 Chapter Three: A Brief History 15 The Beginning 15 Satellite TV 19 The Race to Cable 20 Programming 22 The Battle with FTA Television 23 Pay TV Finances 24 Chapter Four: A Model of Dynamic Competition 27 The Basics 27 Competition and Programme Costs 28 Programming Choice 30 Competitive Pay TV Systems 31 Facilities-based -

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

Liberty Global's Australian Subsidiary AUSTAR Receives a Non-Binding

Liberty Global’s Australian Subsidiary AUSTAR Receives a Non-Binding and Conditional Acquisition Proposal from FOXTEL Englewood, Colorado – May 25, 2011: Liberty Global, Inc. (“Liberty Global”) (NASDAQ: LBTYA, LBTYB and LBTYK) announced today that its 54.2%-owned subsidiary, AUSTAR United Communications Limited (“AUSTAR”), has received an indicative, non-binding and conditional proposal (“Proposal”) from FOXTEL to acquire 100% of AUSTAR for a price of 1.52 Australian dollars (AUD) in cash per share. A copy of AUSTAR’s release to the Australian Securities Exchange is set forth below. The Proposal values AUSTAR at AUD 2.5 billion (including net debt of AUD 525 million at March 31, 2011), representing an enterprise value multiple of approximately 10 times AUSTAR’s consolidated operating cash flow (as customarily defined by Liberty Global) for the 12 months ended March 31, 2011. Assuming definitive agreements are reached on the indicative terms and the conditions to closing are satisfied, Liberty Global would realize gross proceeds of AUD 1.0 billion ($1.1 billion based on the exchange rate at May 24, 2011) for its 688.5 million AUSTAR shares. In light of the non-binding and conditional nature of the Proposal, no assurance can be given that the Proposal will lead to a definitive transaction. Further, to the extent a definitive transaction is entered into, no assurance can be given that the conditions to closing that definitive transaction will ultimately be satisfied. Liberty Global is being advised by Allen & Overy in connection with this Proposal. About Liberty Global, Inc. Liberty Global is the leading international cable operator offering advanced video, voice and broadband internet services to connect its customers to the world of entertainment, communications and information. -

Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories?

Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? Putting the spotlight on cultural and linguistic diversity in television news and current affairs The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? report was prepared on the basis of research and support from the following people: Professor James Arvanitakis (Western Sydney University) Carolyn Cage (Deakin University) Associate Professor Dimitria Groutsis (University of Sydney) Dr Annika Kaabel (University of Sydney) Christine Han (University of Sydney) Dr Ann Hine (Macquarie University) Nic Hopkins (Google News Lab) Antoinette Lattouf (Media Diversity Australia) Irene Jay Liu (Google News Lab) Isabel Lo (Media Diversity Australia) Professor Catharine Lumby (Macquarie University) Dr Usha Rodrigues (Deakin University) Professor Tim Soutphommasane (University of Sydney) Subodhanie Umesha Weerakkody (Deakin University) This report was researched, written and designed on Aboriginal land. Sovereignty over this land was never ceded. We wish to pay our respect to elders past, present and future, and acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities’ ongoing struggles for justice and self-determination. Who Gets to Tell Australian Stories? Executive summary The Who Gets To Tell Australian Stories? report is the first comprehensive picture of who tells, frames and produces stories in Australian television news and current affairs. It details the experience and the extent of inclusion and representation of culturally diverse news and current affairs presenters, commentators and reporters. It is also the first -

This Article Is Downloaded From

This article is downloaded from http://researchoutput.csu.edu.au It is the paper published as Author: D. Cameron Title: Sky News Active: Notes from a digital TV newsroom Conference Name: Media Literacy in the Pacific & Asia Conference Location: Fiji Publisher: JEA Year: 2004 Date: 5-9 December, 2004 Abstract: This paper describes the desktop technology employed in the Sky newsroom to provide eight mini-channels of digital TV news content to subscribers. It outlines the developing workflow that has emerged as Sky News pioneers this form of television news content production in Australia. Many of the staff employed specifically to work on the digital service are recent graduates from journalism courses, and this paper notes some of the entry-level skills required by such employees to produce the digital content. Author Address: [email protected] URL: http://www.usp.ac.fj/journ/jea/docs/JEA04Abstracts.htm http://www.usp.ac.fj/journ/jea/ http://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/R/-?func=dbin-jump- full&object_id=11274&local_base=GEN01-CSU01 CRO identification number: 11274 Sky News Active: Notes from a digital TV newsroom David Cameron Charles Sturt University [email protected] Introduction “Sky News Active – This is News – How you want it, when you want it, 24/7” (Foxtel Digital promotion 2004) Sky News Australia launched its digital interactive service on 5 January 2004, as one of the more than 120 channels and interactive services being offered as part of Foxtel’s $550 million rollout of digital subscriber services in Australia (Kruger 2004). This major initiative is a joint venture of the Seven Network Australia, Publishing and Broadcasting Limited (owner of the Nine television network), and the British Sky Broadcasting (BSkyB) network. -

Fall 2004 Issue of the World Watch One Newsletter

WORLD WATCH ONE NEWSLETTER OF TEAM BANZAI THE BLUE BLAZE IRREGULARS The Official Buckaroo Banzai Fan Club Twentieth Anniversary Edition 2004 APPROVED FOR DISTRIBUTION TO GRADE B CLEARANCES EDITORIAL STAFF Buckaroo Banzai Reno of Memphis Mrs. Johnson Blue Blaze Irregular Big Shoulders Blue Blaze Irregular Dragon Associate Editor BBI the Ice Queen TABLE OF CONTENTS AND CONTRIBUTORS Introductions from the Editors Dragon & Big Shoulders Page 1 World Watch One The Early Years By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 2-3 Banzai Institute's annual Basho Haiku Festival entries Page 3 The year was 1984, what was it like back then...then...By Beverly " Komish" Martin aka John Mr. Pibb Page 4 BBI Call To Action! By Steve “Hard Rock” Mattsson Page 4 The Saga of a Hollywood Orphan: An Interview with W.D. Richter By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 5-10 Watermelon Airlift Delivery Project—Phase 2 Report By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 11 Watermelon Airlift Delivery Project—Phase 2.5 Report By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 12 Captions to Pictures, by the BBIs Page 13 Strike Team Credit Hours Offered Online By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 14 Were Buckaroo Banzai and Hanoi Xan based on Real People? By Steve “Hard Rock” Mattsson Page 15-16 Buckaroo Banzai and the Hong Kong Cavaliers Trading Cards Page 16 An Interview with Earl Mac Rauch By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 17-20 Adder Culture in Brief By Earl Mac Rauch Page 20 Buckaroo Banzai Crossword Puzzle Expert Level By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 21-22 An Interview with Billy Vera aka Pinky Carruthers By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 23-24 Bad Crop Cancels Tour Dates & Production Comic Book Art Page 24 Buckaroo Banzai fandom on the Enet, the FAQ and the Special Edition DVD By Sean "Figment" Murphy Page 25 An Interview with a Red Lectroid By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 26 Mrs. -

Media Concentration: Australia

3/17/2010 Media Concentration: Australia Australia: Overview • Traditional media: highly concentrated - 1-3 dominant players • Newspapers (total daily & Sunday circulation) – News Ltd = 58% approx; Fairfax = 29% approx . • Magazines (circulation: PBL = 44%; Pacific = 27%) • Commercial TV (3 Networks – 77% ads) • Commercial Radio (4 groups - 55% ads) • Telecoms (Telstra 64% total/41% wireless) • Pay TV [Foxtel 63.1% (96): Austar, Optus resell ] – Owners: Telstra 50%, News Ltd 25%, PBL 25% • ISP: Bigpond/Telstra (44%) 1 3/17/2010 AUSTRALIA: Newspapers (1984-2008) 100% 5000 90% 4500 80% 4000 70% 3500 60% 3000 50% 2500 40% 2000 30% 1500 20% 1000 10% 500 0% 0 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 C4 HHI 2 3/17/2010 AUSTRALIA: Magazines (2000-2008) 100% 3000 90% 2500 80% 70% 2000 60% 50% 1500 40% 1000 30% 20% 500 10% 0% 0 1984 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2008 C4 HHI 3 3/17/2010 AUSTRALIA: BROADCAST TELEVISION (1988-2007) (All data relates to fiscal year ending 30 June) 1988 1992 1996 2000 2004 2007 Share of Total Revenue (%) COMMERCIAL TV Seven Network 17.0 21.2 22.8 26.2 22.1 24.9 Nine Network 23.6 24.4 25.7 27.9 25.8 21.5 Ten Network 17.6 11.5 15.4 13.6 17.9 18.2 Other Commercial TV 24.7 24.4 20.4 17.8 20.5 20.0 PUBLIC TV ABC 14.6 16.1 12.5 11.6 10.2 12.4 SBS 2.5 2.5 3.1 3.0 3.5 3.0 Total Revenue ($A million) 1,592.9 2,282.0 2,913.8 3,828.7 4316.7 4,689.9 C4 72.9 73.2 76.5 79.2 76.0 77.0 HHI 1372 1435 1579 1780 1578 1566 Noam Index 380 398 422 514 476 472 AUSTRALIA: BROADCAST TELEVISION (1988-2007) 100% 3000 90% 2500 80% 70% 2000 60% 50% 1500 40% -

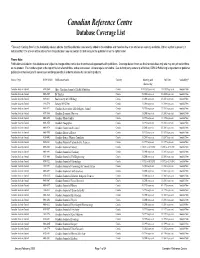

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Publishing is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Country Indexing and Full Text Availability* Abstracting Canadian Academic Journal 0228-586X Alive: Canadian Journal of Health & Nutrition Canada 11/1/1989 to present 11/1/1989 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0005-2949 BC Studies Canada 3/1/2000 to present 3/1/2000 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0829-8211 Biochemistry & Cell Biology Canada 2/1/2001 to present 2/1/2001 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 1916-2790 Botany (19162790) Canada 1/1/2008 to present 1/1/2008 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0846-5371 Canadian -

Draft Version of the Undertaking

ACCC NOT TO OPPOSE AUSTAR ACQUISITION AFTER UNDERTAKING RESOLVES CONCERNS The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission will not oppose the proposed acquisition of AUSTAR United Communications Limited by FOXTEL Management Pty Limited after accepting court-enforceable undertakings from FOXTEL. The undertakings will prevent FOXTEL from acquiring exclusive internet protocol television (IPTV) rights for a range of attractive television program and movie content, including: • Linear channels supplied by independent content suppliers, including more than 60 linear channels that are currently broadcast by FOXTEL and many more that are broadcast internationally • Subscription Video on Demand (SVOD) rights to current or past seasons of television programs that form part of a linear channel supplied by an independent content supplier • Movie linear channels (or movies for inclusion in a linear channel) from more than 50% of the eight major movie studios or more than 50% of the eight specified independent movie studios • SVOD rights to movies, except for an 18 month window in relation to the movie studios from which FOXTEL is not prohibited from acquiring exclusive linear rights. The undertaking further prohibits FOXTEL from exclusively acquiring any movie delivered on a Transactional Video on Demand (TVOD) basis. Importantly, the undertaking also prevents FOXTEL from acquiring exclusive mobile rights to the content referred to above where those rights are sought by competitors to combine with IPTV rights. This means that those competitors will have the opportunity to deliver a seamless and integrated package of programming across a number of devices. A full list of channels that are currently broadcast on the FOXTEL satellite or cable subscription television platform that are covered by the undertaking is at Attachment A. -

Austar Lifesciences Limited 奧星生命科技有限

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult your licensed securities dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional adviser. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Austar Lifesciences Limited (“Company”), you should at once hand this circular and the accompanying form of proxy to the purchaser, the transferee or to the bank, licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. Austar Lifesciences Limited 奧 星 生 命 科 技 有 限 公 司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 6118) PROPOSED GRANT OF GENERAL MANDATES TO ISSUE AND REPURCHASE SHARES; RE-ELECTION OF RETIRING DIRECTORS AND NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING A notice convening the annual general meeting of the Company to be held at 10:00 a.m. on Friday, 29 May 2020 at Conference Room, Rooms 2010-2013, 20th Floor, No. 1018, Changning Road, Changning District, Shanghai, the People’s Republic of China (“Annual General Meeting”) (or any adjournment thereof), is set out on pages AGM-1 to AGM-5 of this circular. -

Suggestions for an Appropriate Use of World Watch List Data (2020) by Christof Sauer1 (With Assistance by Frans Veerman)2

Discussion Texts, no. 1 (3rd edition, 2020) 15 January 2020 Suggestions for an appropriate use of World Watch List data (2020) by Christof Sauer1 (with assistance by Frans Veerman)2 20 Suggestions in brief The World Watch List of Open Doors and nomena, which includes pressure as its underlying statistics are among the well as violence and which reflects the most quoted – and sometimes misquot- everyday experience of the local Chris- ed or misunderstood – instruments for tians. measuring the discrimination or perse- cution of Christians and violations of 4. The reporting period of the WWL religious freedom. The following sug- does not correspond to the calendar gestions and explanations are meant to year. The current WWL 2020 refers to contribute to a better understanding of the time from 1 November 2018 to 31 the World Watch List (WWL) and to help October 2019. to objectify the discussion on the nu- merical assessment of persecution. 5. The number of Christians affected by persecution presented in the WWL 1. It is vital to carefully consider the 2020 (260 million) is a minimum and background and context of the various does not reflect the total figure for the global situation. statistics in order to see clearly what they mean and what they do not mean. 6. The number presented in the WWL of Christians killed in connection with 2. Even though there are many scores their faith in the reporting period equal- and statistics presented in the WWL, the ly does not reflect a total figure for the authors rightly emphasize that it is ulti- global situation but is a minimum num- mately about real human beings and ber for the Top 50 countries on the about their fate, and in this case specifi- World Watch List and further 23 coun- cally about Christians. -

In Gear Week 39 4 May 2020.Pub

Serving the Community since 1985 In Gear 2018—2019 ROTARY CLUB OF BEAUMARIS WEEKLY BULLETIN Number 39 4 May 2020 Presidents Message Next Meetings Well we soldier on in lock down and bleak winter weather which in some ways makes being confined to barracks a little THURSDAY 7 MAY 5:50 FOR 6:00 PM more normal. The Club keeps going on email and ZOOM. But, ROTARY MEETING VIA ZOOM - I have to say, not on the Club Blog which is disappointing. It SPEAKER ELLE GILES could be a lively place for an exchange of views, ideas and RED CROSS BLOOD BANK laughs if only a wider number of members had a go. We had two distinguished guest speakers at our last two THURSDAY 14 MAY 5:50 FOR 6:00 PM ZOOM meetings, Mark Brayshaw, CEO of the AFL Coaches ROTARY MEETING VIA ZOOM - Association, and Peter Hitchener from Channel 9 News (See STRATEGY MEETING reports within). I was inspired by Peter to watch The 9 News the other night and I found he was right when he said it gave THURSDAY 21 MAY us plenty of Melbourne news in contrast to the ABC which 5:50 FOR 6:00 PM ROTARY MEETING VIA ZOOM - seems to be very Sydney dominated. What a great program ROTARY FELLOWSHIP NIGHT - Gail Anderson is delivering to the Club! MUSICAL QUIZ/JACKET DONATION PE Adrian is hard at work setting up his team for the next Ro- tary Year and putting in place a Strategic Plan to guide us into the next 5 years.