Spectrum Maanagement in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers Cento Veljanovski CASE ASSOCIATES Current Issues June 1999 Published by the Institute of Public Affairs ©1999 by Cento Veljanovski and Institute of Public Affairs Limited. All rights reserved. First published 1999 by Institute of Public Affairs Limited (Incorporated in the ACT)␣ A.C.N.␣ 008 627 727 Head Office: Level 2, 410 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Phone: (03) 9600 4744 Fax: (03) 9602 4989 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ipa.org.au Veljanovski, Cento G. Pay TV in Australia: markets and mergers Bibliography ISBN 0 909536␣ 64␣ 3 1.␣ Competition—Australia.␣ 2.␣ Subscription television— Government policy—Australia.␣ 3.␣ Consolidation and merger of corporations—Government policy—Australia.␣ 4.␣ Trade regulation—Australia.␣ I.␣ Title.␣ (Series: Current Issues (Institute of Public Affairs (Australia))). 384.5550994 Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute of Public Affairs. Printed by Impact Print, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056 Contents Preface v The Author vi Glossary vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Pay TV Picture 9 More Choice and Diversity 9 Packaging and Pricing 10 Delivery 12 The Operators 13 Chapter Three: A Brief History 15 The Beginning 15 Satellite TV 19 The Race to Cable 20 Programming 22 The Battle with FTA Television 23 Pay TV Finances 24 Chapter Four: A Model of Dynamic Competition 27 The Basics 27 Competition and Programme Costs 28 Programming Choice 30 Competitive Pay TV Systems 31 Facilities-based -

International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking

telecoms.qxd 9/03/99 10:06 AM Page 1 International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking March 1999 Commonwealth of Australia 1999 ISBN 0 646 33589 8 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Post Office Melbourne Vic 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 1999, International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications Services, Research Report, AusInfo, Melbourne, March. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission, an independent Commonwealth agency, is the Government’s principal review and advisory body on microeconomic policy and regulation. It conducts public inquiries and research into a broad range of economic and social issues affecting the welfare of Australians. The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the community as a whole. Information on the Productivity Commission, its publications and its current work program can be found on the World Wide Web at www.pc.gov.au or by contacting Media and Publications on (03) 9653 2244. -

APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership

EB-2015-0141 Ontario Energy Board IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c.15, (Schedule B); AND IN THE MATTER OF Decision EB-2013-0416/EB- 2014-0247 of the Ontario Energy Board (the “OEB”) issued March 12, 2015 approving distribution rates and charges for Hydro One Networks Inc. (“Hydro One”) for 2015 through 2017, including an increase to the Pole Access Charge; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision of the OEB issued April 17, 2015 setting the Pole Access Charge as interim rather than final; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision and Order issued June 30, 2015 by the OEB granting party status to Rogers Communications Partnership, Allstream Inc., Shaw Communications Inc., Cogeco Cable Inc., on behalf of itself and its affiliate, Cogeco Cable Canada LP, Quebecor Media, Bragg Communications, Packet-tel Corp., Niagara Regional Broadband Network, Tbaytel, Independent Telecommunications Providers Association (ITPA) and Canadian Cable Systems Alliance Inc. (CCSA) (collectively, the “Carriers”); AND IN THE MATTER OF Procedural Order No. 4 of the OEB issued October 26, 2015 setting dates for, inter alia, evidence of the Carriers. APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 EB-2015-0141 APPENDIX A to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 Michael E. Piaskoski SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS Eight years in Rogers Regulatory proceeded by 12 years as a telecom lawyer specializing in regulatory, competition and commercial matters. Bright, professional and ambitious performer who continually exceeds expectations. Expertise in drafting cogent, concise and easy-to-understand regulatory and legal filings and litigation materials. -

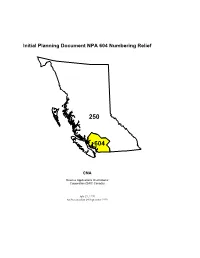

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief 250 604 CNA Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC Canada) July 27, 1999 As Presented on 24 September 1999 INITIAL PLANNING DOCUMENT NPA 604 NUMBERING RELIEF JULY 27, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3. CENTRAL OFFICE CODE EXHAUST .................................................................................................... 2 4. CODE RELIEF METHODS...................................................................................................................... 3 4.1. Geographic Split.............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4.1.2. General Attributes ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Distributed Overlay .......................................................................................................................... 4 4.2.1. Definition ..................................................................................................................................... -

PART a Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100

iTeraTEL Communications CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Title Page ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF This Tariff sets out the rates, terms and conditions applicable to the interconnection arrangements provisioned to providers of telecommunications services and facilities. Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 1 Explanation of Symbols The following symbols are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: A Increase in rate or charge C Change in wording D Discontinued rate or regulation F Reformatting of existing material with no change to rate or charge M Matter moved from its previous location N New wording, rate or charge R Reduction in rate or charge S Reissued matter Abbreviations of Companies Names The following companies names are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: Aliant Aliant Telecom Inc. Bell Bell Canada Bell Aliant Bell Aliant Regional Communications, Limited Partnership IslandTel Island Telecom Inc. MTS MTS Allstream Inc. MTT Maritime Tel & Tel Limited NBTel NBTel NewTel NewTel Communications NorthernTel NorthernTel, Limited Partnership SaskTel SaskTel TBayTel TBayTel TCBC TELUS Communications Company, operating in British Columbia TCC TELUS Communications Company TCI TELUS Communications Company, operating in Alberta TCQ TELUS Communications Company, operating in Quebec Télébec Télébec, société en commandite Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 2 Check Page Issue Date: December 2, 2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2020 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 3 Table of Contents Page Explanation of Symbols 1 Abbreviations of Companies Names 1 Check Page 2 Table of Contents 3 PART A Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100. -

Liberty Global's Australian Subsidiary AUSTAR Receives a Non-Binding

Liberty Global’s Australian Subsidiary AUSTAR Receives a Non-Binding and Conditional Acquisition Proposal from FOXTEL Englewood, Colorado – May 25, 2011: Liberty Global, Inc. (“Liberty Global”) (NASDAQ: LBTYA, LBTYB and LBTYK) announced today that its 54.2%-owned subsidiary, AUSTAR United Communications Limited (“AUSTAR”), has received an indicative, non-binding and conditional proposal (“Proposal”) from FOXTEL to acquire 100% of AUSTAR for a price of 1.52 Australian dollars (AUD) in cash per share. A copy of AUSTAR’s release to the Australian Securities Exchange is set forth below. The Proposal values AUSTAR at AUD 2.5 billion (including net debt of AUD 525 million at March 31, 2011), representing an enterprise value multiple of approximately 10 times AUSTAR’s consolidated operating cash flow (as customarily defined by Liberty Global) for the 12 months ended March 31, 2011. Assuming definitive agreements are reached on the indicative terms and the conditions to closing are satisfied, Liberty Global would realize gross proceeds of AUD 1.0 billion ($1.1 billion based on the exchange rate at May 24, 2011) for its 688.5 million AUSTAR shares. In light of the non-binding and conditional nature of the Proposal, no assurance can be given that the Proposal will lead to a definitive transaction. Further, to the extent a definitive transaction is entered into, no assurance can be given that the conditions to closing that definitive transaction will ultimately be satisfied. Liberty Global is being advised by Allen & Overy in connection with this Proposal. About Liberty Global, Inc. Liberty Global is the leading international cable operator offering advanced video, voice and broadband internet services to connect its customers to the world of entertainment, communications and information. -

Annual Report 2006-2007: Part 2 – Overview

24 international broadcasting then... The opening transmission of Radio Australia in December 1939, known then as “Australia Calling”. “Australia Calling… Australia Calling”, diminishing series of transmission “hops” announced the clipped voice of John Royal around the globe. For decades to come, through the crackle of shortwave radio. It was listeners would tune their receivers in the a few days before Christmas 1939. Overseas early morning and dusk and again at night broadcasting station VLQ 2—V-for-victory, to receive the clearest signals. Even then, L-for-liberty, Q-for-quality—had come alive signal strength lifted and fell repeatedly, to the impending terror of World War II. amid the atmospheric hash. The forerunner of Radio Australia broadcast Australia Calling/Radio Australia based itself in those European languages that were still in Melbourne well south of the wartime widely used throughout South-East Asia at “Brisbane Line” and safe from possible the end of in the colonial age—German, Dutch, Japanese invasion. Even today, one of Radio French, Spanish and English. Australia’s principal transmitter stations is located in the Victorian city of Shepparton. Transmission signals leapt to the ionosphere —a layer of electro-magnetic particles By 1955, ABC Chairman Sir Richard Boyer surrounding the planet—before reflecting summed up the Radio Australia achievement: down to earth and bouncing up again in a “We have sought to tell the story of this section 2 25 country with due pride in our achievements international broadcasting with Australia and way of life, but without ignoring the Television. Neither the ABC nor, later, differences and divisions which are inevitable commercial owners of the service could in and indeed the proof of a free country”. -

Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions

December 2019 Mapping the Information Environment in the Pacific Island Countries: Disruptors, Deficits, and Decisions Lauren Dickey, Erica Downs, Andrew Taffer, and Heidi Holz with Drew Thompson, S. Bilal Hyder, Ryan Loomis, and Anthony Miller Maps and graphics created by Sue N. Mercer, Sharay Bennett, and Michele Deisbeck Approved for Public Release: distribution unlimited. IRM-2019-U-019755-Final Abstract This report provides a general map of the information environment of the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). The focus of the report is on the information environment—that is, the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that shape public opinion through the dissemination of news and information—in the PICs. In this report, we provide a current understanding of how these countries and their respective populaces consume information. We map the general characteristics of the information environment in the region, highlighting trends that make the dissemination and consumption of information in the PICs particularly dynamic. We identify three factors that contribute to the dynamism of the regional information environment: disruptors, deficits, and domestic decisions. Collectively, these factors also create new opportunities for foreign actors to influence or shape the domestic information space in the PICs. This report concludes with recommendations for traditional partners and the PICs to support the positive evolution of the information environment. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor or client. Distribution Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. 12/10/2019 Cooperative Agreement/Grant Award Number: SGECPD18CA0027. This project has been supported by funding from the U.S. -

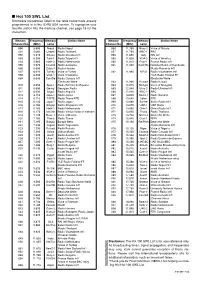

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

This Article Is Downloaded From

This article is downloaded from http://researchoutput.csu.edu.au It is the paper published as Author: D. Cameron Title: Sky News Active: Notes from a digital TV newsroom Conference Name: Media Literacy in the Pacific & Asia Conference Location: Fiji Publisher: JEA Year: 2004 Date: 5-9 December, 2004 Abstract: This paper describes the desktop technology employed in the Sky newsroom to provide eight mini-channels of digital TV news content to subscribers. It outlines the developing workflow that has emerged as Sky News pioneers this form of television news content production in Australia. Many of the staff employed specifically to work on the digital service are recent graduates from journalism courses, and this paper notes some of the entry-level skills required by such employees to produce the digital content. Author Address: [email protected] URL: http://www.usp.ac.fj/journ/jea/docs/JEA04Abstracts.htm http://www.usp.ac.fj/journ/jea/ http://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/R/-?func=dbin-jump- full&object_id=11274&local_base=GEN01-CSU01 CRO identification number: 11274 Sky News Active: Notes from a digital TV newsroom David Cameron Charles Sturt University [email protected] Introduction “Sky News Active – This is News – How you want it, when you want it, 24/7” (Foxtel Digital promotion 2004) Sky News Australia launched its digital interactive service on 5 January 2004, as one of the more than 120 channels and interactive services being offered as part of Foxtel’s $550 million rollout of digital subscriber services in Australia (Kruger 2004). This major initiative is a joint venture of the Seven Network Australia, Publishing and Broadcasting Limited (owner of the Nine television network), and the British Sky Broadcasting (BSkyB) network. -

International Broadcasting in the Pacific Islands

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 271 746 CS 209 768 AUTHOR P.ichstad, Jim TITLE International Broadcasting in the Pacific Islands. PUB DATE Aug 86 NOTE 28p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (69th, Norman, OK, August 36, 1986). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports - Research /Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Industry; Foreign Countries; Intercultural Communication; Mass Media; *Media Research; *News Reporting; *Programing (Broadcast); *Radio; Telecommunications IDENTIFIERS *International Broadcasting; News Sources; *Pacific Islands ABSTRACT A study examined the diversity of news and cultural programing sources available to the Pacific Islands news media from international broadcasting and from related activities of countries outside the region. Questionnaires dealing with the use of international broadcast programs in the Pacific Islands radio services, how managers view listener interest in news and other countries, translation, and monitoring were developed and sent to all Pacific Islands broadcasting services, as well as those international services indicating that their signal could reach the Pacific Islands. Among the conclusions suggested by the data are that (1) island broadcast services make heavy use of international broadcasting for world news, (2) Radio Australia is the leading international broadcaster in the Pacific, and (3) international broadcasting is clearly an important pa-'t of Island broadcasting. (DF) -

49807 Bell AIF Eng Clean

BELL CANADA ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2001 APRIL 15, 2002 2001 T ABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Information Form for the year ended December 31, 2001 April 15, 2002 Documents Incorporated by Reference . .1 Documents incorporated by reference Part of Annual Information Form in Trade-marks . .1 Document which incorporated by reference Item 1 • Corporate Structure of Bell Canada . .2 Portions of the 2001 Bell Canada Financial Information Item 5 Item 2 • General Development of Bell Canada . .2 Item 3 • Business of Bell Canada . .3 General . .3 Principal Service Area . .5 Subsidiaries and Associated Companies . .5 Regulation . .8 Competition . .12 Capital Expenditures . .15 Environment . .15 Employee Relations . .16 Legal Proceedings . .16 Trade-marks Certain Contracts . .17 Owner Trade-mark Forward-Looking Statements . .18 Bell Canada Rings & Head Design Risk Factors . .18 (Bell Canada corporate logo) Bell Item 4 • Selected Financial Information (Consolidated) . .20 Bell World Item 5 • Management’s Discussion and Analysis . .21 Espace Bell Sympatico Item 6 • Market for the Securities of Bell Canada . .21 Bell ActiMedia Inc. Yellow Pages Item 7 • Directors and Officers of Bell Canada . .21 Bell Mobility Inc. / Bell Mobilité inc. Mobile Browser Item 8 • Additional Information . .23 Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. First Rate Schedule – Directors’ and Officers’ Remuneration . .24 Stentor Resource Centre Inc. / Datapac Centre de ressources Stentor Inc. Megalink SmartTouch AT&T Corp. AT&T MCI Communications Corporation Hyperstream OnStar Corporation Onstar NOTES: (1) Unless the context indicates otherwise, “Bell Canada” refers to Bell Canada and its subsidiaries Yahoo! Inc. Yahoo! and associated companies. (2) All dollar figures are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise indicated.