State of the World 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Facts and Produced Graphs, Tables, and Text Well As for the Information Many People Pro- Boxes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Farm Animals

Animal Welfare Issues 4. Farm Animals Introduction Intensive Farming Fur and skin farming Exotic/cruel foods Markets Live Transport Slaughter Genetic Engineering Mutilations Legislative Bans Alternatives Science Feeding the World Annex 1 - Scientific Quotations Further Resources Introduction In terms of numbers of animals affected, factory farming is the largest animal welfare concern in the world. FAO statistics show the global production of meat has risen from 136,219,000 tonnes for 1979-81 to 260,098,000 tonnes for 2004. The following statistics give an indication of the numbers of different species involved and the numbers exported. Farmed animal numbers (FAO 2003): Pigs 956 million Chickens 16,605 million Cattle 1,371 million Sheep 1,024 Numbers of farm animals exported alive (FAO 2002): Pigs 18 million Chickens 837 million Cattle 8 million Sheep 19 million Billions of farm animals throughout the world are reared behind the closed doors of the factory farm. Many farm animals suffer greatly in transport slaughter and in factory farms: where they are caged, crammed and confined, forced to grow super-fast, and pushed to their physical limits in the quest for ever-more meat, milk or eggs. However, animal protection activity often neglects farm animals, because their suffering is hidden. The rapid rise of factory farming systems in the USA and Europe took place in the latter half of the last century. Factory farming systems are characterised by large numbers of farm animals being caged or crated, and crammed into (typically) windowless sheds. 1 Animal Welfare Issues Three classic factory farm methods were clear examples of the suffering caused by such methods: veal crates for calves, stall and tether-cages for pregnant pigs, and battery cages for laying hens. -

Fall 2004 Issue of the World Watch One Newsletter

WORLD WATCH ONE NEWSLETTER OF TEAM BANZAI THE BLUE BLAZE IRREGULARS The Official Buckaroo Banzai Fan Club Twentieth Anniversary Edition 2004 APPROVED FOR DISTRIBUTION TO GRADE B CLEARANCES EDITORIAL STAFF Buckaroo Banzai Reno of Memphis Mrs. Johnson Blue Blaze Irregular Big Shoulders Blue Blaze Irregular Dragon Associate Editor BBI the Ice Queen TABLE OF CONTENTS AND CONTRIBUTORS Introductions from the Editors Dragon & Big Shoulders Page 1 World Watch One The Early Years By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 2-3 Banzai Institute's annual Basho Haiku Festival entries Page 3 The year was 1984, what was it like back then...then...By Beverly " Komish" Martin aka John Mr. Pibb Page 4 BBI Call To Action! By Steve “Hard Rock” Mattsson Page 4 The Saga of a Hollywood Orphan: An Interview with W.D. Richter By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 5-10 Watermelon Airlift Delivery Project—Phase 2 Report By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 11 Watermelon Airlift Delivery Project—Phase 2.5 Report By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 12 Captions to Pictures, by the BBIs Page 13 Strike Team Credit Hours Offered Online By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 14 Were Buckaroo Banzai and Hanoi Xan based on Real People? By Steve “Hard Rock” Mattsson Page 15-16 Buckaroo Banzai and the Hong Kong Cavaliers Trading Cards Page 16 An Interview with Earl Mac Rauch By Dan "Big Shoulders" Berger Page 17-20 Adder Culture in Brief By Earl Mac Rauch Page 20 Buckaroo Banzai Crossword Puzzle Expert Level By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 21-22 An Interview with Billy Vera aka Pinky Carruthers By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 23-24 Bad Crop Cancels Tour Dates & Production Comic Book Art Page 24 Buckaroo Banzai fandom on the Enet, the FAQ and the Special Edition DVD By Sean "Figment" Murphy Page 25 An Interview with a Red Lectroid By Alan "Dragon" Smith Page 26 Mrs. -

Centre for Animal Welfare News 2017

2017 News and Events from the University of Winchester’s Centre for Animal Welfare CAW Acting Director speaks out on Brexit, sentience and animal welfare 12 December 2017 Dr Steven McCulloch, Acting Director of CAW, has published two articles on Brexit, sentience and animal welfare. Sentience and animal welfare has received substantial media attention after Parliament voted against an amendment to the EU Withdrawal Bill tabled by Caroline Lucas MP. Dr McCulloch's first article, Brexit, Animal Sentience and Democracy, describes the moral atrocities committed against animals when their sentience has been denied. In the article he argues that the historical denial of sentience and its consequences in itself means that government should formally recognise it in law. The second article The Greatness Of A Nation Can Be Judged By How It Treats Its Animals is critical of the Conservative government policy to reject incorporating Article 13 in the EU Withdrawal Bill. How clever are the animals we keep? World's first Professor of Animal Welfare, gives lecture at CAW event 28 November 2017 Donald Broom, Emeritus Professor at the University of Cambridge (pictured above centre with Dr Steve McCulloch and Professor Joy Carter), gave a CAW evening lecture on How clever are the animals we keep? on 27 Nov 2017. Donald Broom was the first person to be appointed Professor of Animal Welfare in the world. Professor Joy Carter, Vice Chancellor at Winchester, introduced the CAW event, which was a great success. Over one hundred staff, students and members of the public attended. Watch the video of the Centre for Animal Welfare lecture How clever are the animals we keep? by Professor Donald Broom. -

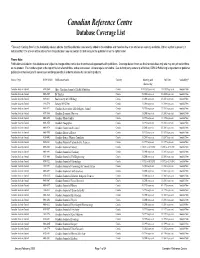

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List

Canadian Reference Centre Database Coverage List *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. The numbers given at the top of this list reflect all titles, active and ceased. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Publishing is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Source Type ISSN / ISBN Publication Name Country Indexing and Full Text Availability* Abstracting Canadian Academic Journal 0228-586X Alive: Canadian Journal of Health & Nutrition Canada 11/1/1989 to present 11/1/1989 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0005-2949 BC Studies Canada 3/1/2000 to present 3/1/2000 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0829-8211 Biochemistry & Cell Biology Canada 2/1/2001 to present 2/1/2001 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 1916-2790 Botany (19162790) Canada 1/1/2008 to present 1/1/2008 to present Available Now Canadian Academic Journal 0846-5371 Canadian -

Suggestions for an Appropriate Use of World Watch List Data (2020) by Christof Sauer1 (With Assistance by Frans Veerman)2

Discussion Texts, no. 1 (3rd edition, 2020) 15 January 2020 Suggestions for an appropriate use of World Watch List data (2020) by Christof Sauer1 (with assistance by Frans Veerman)2 20 Suggestions in brief The World Watch List of Open Doors and nomena, which includes pressure as its underlying statistics are among the well as violence and which reflects the most quoted – and sometimes misquot- everyday experience of the local Chris- ed or misunderstood – instruments for tians. measuring the discrimination or perse- cution of Christians and violations of 4. The reporting period of the WWL religious freedom. The following sug- does not correspond to the calendar gestions and explanations are meant to year. The current WWL 2020 refers to contribute to a better understanding of the time from 1 November 2018 to 31 the World Watch List (WWL) and to help October 2019. to objectify the discussion on the nu- merical assessment of persecution. 5. The number of Christians affected by persecution presented in the WWL 1. It is vital to carefully consider the 2020 (260 million) is a minimum and background and context of the various does not reflect the total figure for the global situation. statistics in order to see clearly what they mean and what they do not mean. 6. The number presented in the WWL of Christians killed in connection with 2. Even though there are many scores their faith in the reporting period equal- and statistics presented in the WWL, the ly does not reflect a total figure for the authors rightly emphasize that it is ulti- global situation but is a minimum num- mately about real human beings and ber for the Top 50 countries on the about their fate, and in this case specifi- World Watch List and further 23 coun- cally about Christians. -

VISION for FAIR FOOD and FARMING © Istockphoto Vision for Those Who Wish to Know More

ciwf.org.uk/raffle VISION FOR FAIR FOOD AND FARMING © iStockphoto Vision for Fair Food and Farming Good health by ensuring universal access to sufficient and nutritious food We are facing a dilemma: the world’s population is growing, but the planet In 2019, around 690 million people in the world were estimated to be suffering from under-nutrition itself has little viable land left to farm, and water resources are under severe (FAO 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic may well have added over 100 million more to that figure. pressure. Many people are suffering from hunger, and the environment has Currently it is the poor who bear the brunt of this situation, and millions of children go to sleep hungry, night after night. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) aim for No been damaged by inappropriate farming methods. New technologies may Poverty and Zero Hunger by 2030 (SDGs 2015). Without radical change to our food and farming increase productivity, but small-scale farmers may not have access to them. systems, it will be a challenge to achieve this worthy goal. We urgently need a new vision for the future of food and farming, one that enhances the health of humanity and the planet itself, including animals, The marketing of food and global trading in food A University of Minnesota paper concludes that both wild and domesticated. commodities must be reformed so that prices of for every 100 calories of grain fed to animals, we food staples are maintained at an affordable level get only about 40 new calories of milk, 22 calories for those on low incomes. -

Europe Needs a Food Not Feed Policy

Europe Needs a Food not Feed Policy Philip Lymbery, Peter Stevenson and Carol McKenna Compassion in World Farming, River Court, Mill Lane, Godalming, GU7 1EZ, UK [email protected] Paper prepared for presentation at the 148th seminar of the EAAE, ‘’Does Europe need a Food Policy?”, Brussels, Belgium, 30 November – 1 December, 2015 Copyright 2015 Philip Lymbery, Peter Stevenson and Carol McKenna. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non- commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. EUROPE NEEDS A FOOD NOT FEED POLICY Abstract Current European agricultural policies serve to prop up industrial animal agriculture, which doesn’t produce food but wastes it. A sustainable food policy would focus on producing healthy food for people, and not feed for animals, whilst protecting the environment. When considering sustainability in value chains, a key fact commonly overlooked is that nearly two thirds of EU cereals are fed to farm animals, with enormous associated loss of ~70%: for every 100 food calories of edible crops fed to livestock just 30 calories are produced in the form of meat and milk. If this human-edible grain were fed to people, it could feed an extra 3 billion. Such losses are not restricted to grain: around a quarter of the world’s landed fish catch never reaches a human mouth, much of it is diverted to feed industrially reared fish, pigs or poultry. Animals’ inefficiency in converting human-edible crops into meat and milk brings other inefficiencies in its train: It is a wasteful use not just of the crops but also of the land, water and energy used to grow them. -

World Watch List 2021 Report Wwl 2021Report Contents

WORLD WATCH LIST 2021 REPORT WWL 2021REPORT CONTENTS 02 An Introduction To The World Watch List 03 Trends In Persecution 04 Top 10 Pressure & Violence Comparison 05 Highest Risers 06 Case Study: North Africa 07 Entering The Top 50 In 2021 09 Case Study: North Korea 12 Complete World Watch List 2021 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE WORLD WATCH LIST The Open Doors World Watch List is an annual report that ranks the countries where Christians face the most persecution and discrimination. Countries are ranked by the severity of persecution of Christians, calculated by analysing the level of violence plus the pressure experienced in five spheres of life: private, family, community, church and national. Each country has a point score out of a maximum 100 points. 81–100 Extreme level of persecution and discrimination 61–80 Very high level of persecution and discrimination 41–60 High level of persecution and discrimination Persecution has continued to rise for 14 years. Across the top 50, pressure is rising. The total points of the top 50 have gone up and the threshold to get into the top 50 has risen again in 2021. METHODOLOGY OF THE WORLD WATCH LIST The World Watch List is a global research tool, in its 29th year in 2021. It was initially conceived as a tool to guide Open Doors’ fieldwork, now in over 70 countries worldwide. Released at the beginning of each year, the list uses extensive research and surveys, data from Open Doors’ fieldworkers and external experts to quantify and analyse persecution worldwide. It is certified by the International Institute for Religious Freedom (www.iirf.eu). -

ACMA Investigation Into Coverage by Australian Television Broadcasters of the Christchurch Terrorist Attack

ACMA investigation into coverage by Australian television broadcasters of the Christchurch terrorist attack JULY 2019 Canberra Red Building Benjamin Offices Chan Street Belconnen ACT PO Box 78 Belconnen ACT 2616 T +61 2 6219 5555 F +61 2 6219 5353 Melbourne Level 32 Melbourne Central Tower 360 Elizabeth Street Melbourne VIC PO Box 13112 Law Courts Melbourne VIC 8010 T +61 3 9963 6800 F +61 3 9963 6899 Sydney Level 5 The Bay Centre 65 Pirrama Road Pyrmont NSW PO Box Q500 Queen Victoria Building NSW 1230 T +61 2 9334 7700 or 1800 226 667 F +61 2 9334 7799 Copyright notice https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ With the exception of coats of arms, logos, emblems, images, other third-party material or devices protected by a trademark, this content is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. We request attribution as © Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Communications and Media Authority) 2019. All other rights are reserved. The Australian Communications and Media Authority has undertaken reasonable enquiries to identify material owned by third parties and secure permission for its reproduction. Permission may need to be obtained from third parties to re-use their material. Written enquiries may be sent to: Manager, Editorial Services PO Box 13112 Law Courts Melbourne VIC 8010 Email: [email protected] Executive summary A terrorist attack live streamed by its alleged perpetrator On 15 March 2019 a violent terrorist attack took place in Christchurch, New Zealand leading to a large number of deaths and significant injuries to many innocent people. -

A Digital Agenda1

SRJ 35.1 v1 26/3/02 2:15 PM Page 21 A DIGITAL AGENDA1 Jock Given Abstract This article discusses progress with the introduction of digital TV and radio in Australia and the implications for Australian public service broadcasters. It argues that digital technologies provide powerful tools for the ABC and the SBS to apply to their existing activities. However, realising this potential will be expensive. It also brings with it some threats to the independence of the organizations. The article concludes by suggesting that, even if Australia’s public service broadcasters did not already exist, many of their central characteristics would be invaluable features in some organizations with a central role in the emerging media and communications landscape. These characteristics include their particular institutional structures, their size, their primary emphasis on “content,” and the comprehensiveness or inclusiveness of their mandates. Introduction This paper is primarily about Australian public service broadcasting. Thinking about its future is sometimes confused by applying to it the frames derived elsewhere, where public service broadcasters are very different. Australian public service broadcasting comprises two broadcasting institutions, the ABC and the SBS, which both offer TV and radio services and whose primary responsibilities are to offer “comprehensive” and “multicultural” services respectively. This is significantly different from even those countries with whom compar- isons are most often drawn: the UK, where all free-to-air TV broad- casters have carried “public service responsibilities” (see for example Department of National Heritage 11–13) and the “niche” broadcaster Channel 4 does not provide radio services; New Zealand, where there are separate public corporations providing TV and radio services; and Canada, where there is a single, national public service broadcaster. -

Complaint Vs Freedom Food with Charity Commission

Charity Commission PO Box 211 BOOTLE L20 7YX Online complaint form Scottish Chairty Regulator (OSCR) 2nd Floor Quadrant House 9 Riverside Drive Dundee DD1 4NY Email: [email protected] 12 May 2017 Complaint against Freedom Food (RSPCA Assured) Please consider this a formal complaint against Freedom Food (re-branded as RSPCA Assured in 2016) - as registered by the Scottish Charity Regulator as Freedom Food Limited, SC038199 and registered by the Charity Commission as Charity no. 1059879 (and Company no. 2723670). Freedom For Fish (a campaign recently launched by the Global Alliance Against Industrial Aquaculture) presents evidence below and in various attachments sourced from data obtained via FOI from the Scottish Environment Protection Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage (see next email) detailing reasons why Freedom Food should not be afforded charitable status. Our complaint and submitted evidence focuses solely on farmed salmon and focuses on: 1) Freedom Food Promotes Not Prevents Cruelty to Animals Via Salmon Farming Accreditation 2) Freedom Food is Commercial NOT Charitable 3) Freedom Food Accredited Scottish Salmon is a Welfare Nightmare 4) Freedom Food Accounts for ca. 70% of Scottish Salmon Farming Production GAAIA has complained previously with regard to Freedom Food's accreditation of farmed salmon in letters dated November 2015; August 2015; and July 2012. Suffice to say that GAAIA has never received a satisfactory reply and has been in no way reassured. The only assurance is that the RSPCA are still promoting the killing of seals and other cruel and inhumane animal welfare problems via accreditation of Freedom Food/RSPCA Assured farmed salmon. -

The Official Veganuary Starter Kit

#Veganuary2021 THE OFFICIAL VEGANUARY STARTER KIT 2021 EDITION The Official Veganuary Starter Kit CONTENTS WHY VEGAN? Animals Health WELCOME Obesity Heart disease WHAT IS VEGAN? Type 2 diabetes Cancer Global health NUTRITION Zoonotic diseases Antibiotic resistance Protein The health of our planet Calcium Climate change Iron Water shortages Omega-3 Pollution Iodine Deforestation and species loss Vitamin B12 Dying Oceans - including plastics Sustainability VEGAN KIDS Feeding the world Protecting their future Local versus vegan OUR TOP TEN TIPS TEN COMMONLY-ASKED TO GET YOU STARTED QUESTIONS ABOUT Planning VEGANISM Accidentally vegan foods What do vegans eat? Transition foods Do fish feel pain? Do plants feel pain? Veganise already-loved dishes Is soya the cause of deforestation? When you’re ready, branch out What would happen to the animals if we Keep snacks to hand did not eat them? Be bold - try lots of new recipes and products Why does plant milk curdle in hot drinks HappyCow and how do I stop it? Find new friends for support Almonds and water Be kind to yourself if you make a mistake What do I do with leather bags and shoes? Can you be a successful vegan athlete? Do you need milk for strong bones? MEAL PLANNING What difference can one person make? RECOMMENDED RECIPE FIVE LIFE-CHANGING SITES AND BOOKS BOOKS TO READ EATING OUT FIVE LIFE-CHANGING On the go FILMS TO SEE THIS IS AN INTERACTIVE PDF — JUMP TO EACH TOPIC BY CLICKING THE TITLE The Official Veganuary Starter Kit WELCOME! Thank you for signing up to take part in Veganuary and pledging to try vegan for 31 days.