Bordering on Britishness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download This Report

Report GIBRALTAR A ROCK AND A HARDWARE PLACE As one of the four island iGaming hubs in Europe, Gibraltar’s tiny 6.8sq.km leaves a huge footprint in the gaming sector Gibraltar has long been associated with Today, Gibraltar is self-governing and for duty free cigarettes, booze and cheap the last 25 years has also been electrical goods, the wild Barbary economically self sufficient, although monkeys, border crossing traffic jams, the some powers such as the defence and Rock and online gaming. foreign relations remain the responsibility of the UK government. It is a key base for It’s an odd little territory which seems to the British Royal Navy due to its strategic continually hover between its Spanish location. and British roots and being only 6.8sq.km in size, it is crammed with almost 30,000 During World War II the area was Gibraltarians who have made this unique evacuated and the Rock was strengthened zone their home. as a fortress. After the 1968 referendum Spain severed its communication links Gibraltar is a British overseas peninsular that is located on the southern tip of Spain overlooking the African coastline as GIBRALTAR IS A the Atlantic Ocean meets the POPULAR PORT Mediterranean and the English meet the Spanish. Its position has caused a FOR TOURIST continuous struggle for power over the CRUISE SHIPS AND years particularly between Spain and the British who each want to control this ALSO ATTRACTS unique territory, which stands guard over the western Mediterranean via the Straits MANY VISITORS of Gibraltar. FROM SPAIN FOR Once ruled by Rome the area fell to the DAY VISITS EAGER Goths then the Moors. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

Infogibraltar Servicio De Información De Gibraltar

InfoGibraltar Servicio de Información de Gibraltar Comunicado Gobierno de Gibraltar: Ministerio de Deportes, Cultura, Patrimonio y Juventud Comedia Llanita de la Semana Nacional Gibraltar, 21 de julio de 2014 El Ministerio de Cultura se complace en anunciar los detalles de la Comedia Yanita de la Semana Nacional (National Week) de este año, la cual se representará entre el lunes 1 de septiembre y el viernes 5 de septiembre de 2014. La empresa Santos Productions, responsable de organizar el evento, está muy satisfecha de presentar ‘To be Llanito’ (Ser llanito), una comedia escrita y dirigida por Christian Santos. La producción será representada en el Teatro de John Mackintosh Hall, y las actuaciones darán comienzo a las 20 h. Las entradas tendrán un precio de 12 libras y se pondrán a la venta a partir del 13 de agosto en the Nature Shop en La Explanada (Casemates Square). Para más información, contactar con Santos Productions mediante el e‐mail: info@santos‐ productions.com Nota a redactores: Esta es una traducción realizada por la Oficina de Información de Gibraltar. Algunas palabras no se encuentran en el documento original y se han añadido para mejorar el sentido de la traducción. El texto válido es el original en inglés. Para cualquier ampliación de esta información, rogamos contacte con Oficina de Información de Gibraltar Miguel Vermehren, Madrid, [email protected], Tel 609 004 166 Sandra Balvín, Campo de Gibraltar, [email protected], Tel 661 547 573 Web: www.infogibraltar.com, web en inglés: www.gibraltar.gov.gi/press‐office Twitter: @infogibraltar 21/07/2014 1/2 HM GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR MINISTRY FOR SPORTS, CULTURE, HERITAGE & YOUTH 310 Main Street Gibraltar PRESS RELEASE No: 385/2014 Date: 21st July 2014 GIBRALTAR NATIONAL WEEK YANITO COMEDY The Ministry of Culture is pleased to announce the details for this year’s National Week Yanito Comedy, which will be held from Monday 1st September to Friday 5th September 2014. -

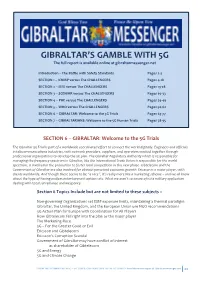

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but -

Innovation Edition

1 Issue 36 - Summer 2019 iMindingntouch Gibraltar’s Business INNOVATION EDITION INSIDE: Hungry Monkey - Is your workplace The GFSB From zero to home inspiring Gibtelecom screen hero innovation & Innovation creativity? Awards 2019 intouch | ISSUEwww.gfsb.gi 36 | SUMMER 2019 www.gibraltarlawyers.com ISOLAS Trusted Since 1892 Property • Family • Corporate & Commercial • Taxation • Litigation • Trusts Wills & Probate • Shipping • Private Client • Wealth management • Sports law & management For further information contact: [email protected] ISOLAS LLP Portland House Glacis Road PO Box 204 Gibraltar. Tel: +350 2000 1892 Celebrating 125 years of ISOLAS CONTENTS 3 05 MEET THE BOARD 06 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 08 HUNGRY MONKEY - FROM ZERO TO HOME SCREEN HERO 12 WHAT’S THE BIG iDEA? 14 IS YOUR WORKPLACE INSPIRING INNOVATION & CREATIVITY? 12 16 NETWORKING, ONE OF THE MAIN REASONS PEOPLE JOIN THE GFSB WHAT’S THE BIG IDEA? 18 SAVE TIME AND MONEY WITH DESKTOPS AND MEETINGS BACKED BY GOOGLE CLOUD 20 NOMNOMS: THE NEW KID ON THE DELIVERY BLOCK 24 “IT’S NOT ALL ABOUT BITCOIN”: CRYPTOCURRENCY AND DISTRIBUTED LEDGER TECHNOLOGY 26 JOINT BREAKFAST CLUB WITH THE WOMEN IN BUSINESS 16 26 NETWORKING, ONE OF THE JOINT BREAKFAST CLUB WITH 28 GFSB ANNUAL GALA DINNER 2019 MAIN REASONS PEOPLE JOIN THE WOMEN IN BUSINESS THE GFSB 32 MEET THE GIBRALTAR BUSINESS WITH A TRICK UP ITS SLEEVE 34 SHIELDMAIDENS VIRTUAL ASSISTANTS - INDEFATIGABLE ASSISTANCE AND SUPPORT FOR ALL BUSINESSES 36 ROCK RADIO REFRESHES THE AIRWAVES OVER GIBRALTAR 38 WHEN WHAT YOU NEED, NEEDS TO HAPPEN RIGHT -

Refeg 8/2020

REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS FRONTERIZOS DEL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR REFEG (NUEVA ÉPOCA) ISSN: 1698-1006 GRUPO SEJ-058 PAIDI 48 ESTADO DE LOS MECANISMOS JURÍDICO- POLÍTICOS TENDENTES A FAVORECER EL RETORNO DE GIBRALTAR A LA SOBERANÍA ESPAÑOLA GUILLERMO SALVADOR SALVADOR Graduado en Derecho. Máster en Derecho Parlamentario UCM [email protected] REFEG 8/2020 ISSN: 1698-1006 GRUPO DE INVESTIGACION SEJ-058 CENTRO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIALES Y MIGRATORIAS DEL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR SALVADOR SALVADOR REFEG 8/2020: 1-24. ISSN: 1698- 1006 0 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS FRONTERIZOS DEL ESTRECHO DE GIBRALTAR R ESTADO DE LOS MECANISMOS JURÍDICO-POLÍTICOS TENDENTES A FAVORECER EL RETORNO DE GIBRALTAR A LA SOBERANÍA ESPAÑOLA GUILLERMO SALVADOR SALVADOR Graduado en Derecho. Máster en Derecho Parlamentario UCM [email protected] ESTADO DE LOS MECANISMOS JURÍDICO- POLÍTICOS TENDENTES A FAVORECER EL RETORNO DE GIBRALTAR A LA SOBERANÍA ESPAÑOLA SUMARIO: I. INTRODUCCIÓN. CIA O IMPRACTICABILIDAD DE II. EL RÉGIMEN JURÍDICO-POLÍ- LOS POSIBLES REGÍMENES ADMI- TICO ACTUAL DEL GIBRALTAR NISTRATIVOS ESTANDARIZADOS BRITÁNICO. 1. BREVÍSIMA RELA- APLICABLES A GIBRALTAR EN EL 1 CIÓN DE LA CONFORMACIÓN DE CASO DE QUE SE REINTEGRARA A LA INSTITUCIONALIDAD GIBRAL- ESPAÑA Y ANDALUCÍA. IV. CON- TAREÑA. 2. GIBRALTAR DESDE CLUSIÓN: ¿QUÉ GANARÍA Y QUÉ 1969 HASTA NUESTROS DÍAS. LA PERDERÍA UN GIBRALTAR ESPA- ORDEN CONSTITUCIONAL DE GI- ÑOL INTEGRADO DENTRO DE BRALTAR DE 2006. III. INSUFICIEN- ANDALUCÍA? V. BIBLIOGRAFÍA. RESUMEN: El presente artículo Andalucía, con la pretensión de determi- pretende abordar la Historia institucional nar si realmente el Estado y la Autonomía de Gibraltar, desde su captura por los bri- están preparados para el desafío que su- tánicos en 1704 hasta nuestros días. -

Wednesday 17Th March 2021

P R O C E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.40 p.m. – 7.40 p.m. Gibraltar, Wednesday, 17th March 2021 Contents Questions for Oral Answer ..................................................................................................... 3 Employment, Health and Safety and Social Security........................................................................ 3 Q519/2020 Health and safety inspections at GibDock – Numbers in 2019 and 2020 ............. 3 Q520/2020 Maternity grants and allowances – Reason for delays in applications ................. 3 Q521/2020 Carers’ allowance – How to apply ......................................................................... 5 Environment, Sustainability, Climate Change and Education .......................................................... 6 Q547/2021 Dog fouling – Number of fines imposed ................................................................ 6 Q548-50/2020 Barbary macaques – Warning signs and safety measures ............................... 7 Q551/2020 Governor’s Street – Tree planting ......................................................................... 8 Q552/2020 School buses – Rationale for cancelling ................................................................ 9 Q553/2020 Fly tipping – Number of complaints and prosecutions ......................................... 9 Q554/2020 Waste Treatment Plan – Update ......................................................................... 11 Q555/2020 Water production – Less energy-intensive -

Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity

canessa 6 13/07/2018 15:33 Page 102 Chapter Four ‘An Example to the World!’: Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity Luis Martínez, Andrew Canessa and Giacomo Orsini Ethnicity is an essential concept to explain how national identities are articulated in the modern world. Although all countries are ethnically diverse, nation-formation often tends to structure around discourses of a core ethnic group and a hegemonic language.1 Nationalists invent a dominant – and usually essentialised – narrative of the nation, which often set aside the languages, ethnicities, and religious beliefs of minori- ties inhabiting the nation-state’s territory.2 In the last two centuries, many nation-building processes have excluded, removed or segregated ethnic groups from the national narrative and access to rights – even when they constituted the majority of the population as in Bolivia.3 On other occasions, the hosting state assimilated immigrants and ethnic minorities, as they adopted the core-group culture and way of life. This was the case of many immigrant groups in the USA, where, in the 1910s and 1920s, assimilation policies were implemented to acculturate minorities, ‘in attempting to win the immigrant to American ways’.4 In the 1960s, however, the model of a nation-state as being based on a single ethnic group gave way to a model that recognised cultural diver- sity within a national territory. The civil rights movements changed the politics of nation-formation, and many governments developed strate- gies to accommodate those secondary cultures in the nation-state. Multiculturalism is what many poly-ethnic communities – such as, for instance, Canada and Australia – used to redefine their national identi- ties through the recognition of internal cultural difference. -

Tuesday 11Th June 2019

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T MORNING SESSION: 10.01 a.m. – 12.47 p.m. Gibraltar, Tuesday, 11th June 2019 Contents Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued ........................................ 2 The House adjourned at 12.47 p.m. ........................................................................................ 36 _______________________________________________________________________________ Published by © The Gibraltar Parliament, 2019 GIBRALTAR PARLIAMENT, TUESDAY, 11th JUNE 2019 The Gibraltar Parliament The Parliament met at 10.01 a.m. [MR SPEAKER: Hon. A J Canepa CMG, GMH, OBE, in the Chair] [CLERK TO THE PARLIAMENT: P E Martinez Esq in attendance] Appropriation Bill 2019 – For Second Reading – Debate continued Clerk: Tuesday, 11th June 2019 – Meeting of Parliament. Bills for First and Second Reading. We remain on the Second Reading of the Appropriation 5 Bill 2019. Mr Speaker: The Hon. Dr John Cortes. Minister for the Environment, Energy, Climate Change and Education (Hon. Dr J E Cortes): Good morning, Mr Speaker. I rise for my eighth Budget speech conscious that being the last one in the electoral cycle it could conceivably be my last. While resisting the temptation to summarise the accomplishments of this latest part of my life’s journey, I must however comment very briefly on how different Gibraltar is today from an environmental perspective. In 2011, all you could recycle here was glass. There was virtually no climate change awareness, no possibility of a Parliament even debating let alone passing a motion on the climate emergency. -

The Construction of Gibraltarian Identity in MG

The Line and the Limit of Britishness: The Construction ∗ of Gibraltarian Identity in M. G. Sanchez’s Writing ANA Mª MANZANAS CALVO Institution address: Universidad de Salamanca. Departamento de Filología Inglesa. Facultad de Filología. Plaza de Anaya s/n. 37008 Salamanca. Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0001-9830-638X Received: 30/01/2017. Accepted 25/02/2017 How to cite this article: Manzanas Calvo, Ana Mª “The Line and the Limit of Britishness: The Construction of Gibraltarian Identity in M. G. Sanchez’s Writing.” ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies 38 (2017): 27‒45. DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.24197/ersjes.38.2017.27-45 Abstract: From Anthony Burgess’s musings during the Second World War to recent scholarly assessments, Gibraltar has been considered a no man’s literary land. However, the Rock has produced a steady body of literature written in English throughout the second half of the twentieth century and into the present. Apparently situated in the midst of two identitary deficits, Gibraltarian literature occupies a narrative space that is neither British nor Spanish but something else. M. G. Sanchez’s novels and memoir situate themselves in this liminal space of multiple cultural traditions and linguistic contami-nation. The writer anatomizes this space crossed and partitioned by multiple and fluid borders and boundaries. What appears as deficient or lacking from the British and the Spanish points of view, the curse of the periphery, the curse of inhabiting a no man’s land, is repossessed in Sanchez’s writing in order to flesh out a border culture with very specific linguistic and cultural traits. -

May 1St – June 20Th

Programme of Events st th May 1 – June 20 May 2019 Wednesday 1st May 11am to 7pm May Day Celebrations Organised by the Gibraltar Cultural Services Featuring SNAP!, Dr Alban, Rozalla, DJ’s No Limits Entertainment, Layla Rose, Art in Movement, Transitions, Mediterranean Dance School, Show Dance Company, JF Dance, the Gibraltar Youth Choir and much more Casemates Square For further information please contact GCS Events Department on 20067236 or email: [email protected] Saturday 4th May 11.30am to 5.30pm Fund Raising Event Organised by the Bassadone Automotive Group Casemates Square For further information please contact Rachel Goodman on telephone number 20059100. 8.30pm to 10.30pm Art Dance 2019 John Mackintosh Square Organised by Art Dance Gibraltar. International professional artists will be showing their works. Local dancers/artists will be invited to participate. For further information please contact [email protected] . 12 noon Re-enactment Society march along Main Street to Casemates Square Monday 7th May – Friday 17th May 10am to 6pm Art Exhibition by Aaron Seruya Fine Arts Gallery, Casemates Square For further information please contact telephone 20052126 or email: [email protected] Wednesday 8th May – Thursday 9th May 8:00pm - 9:00pm Zarzuela – ‘La del Manojo de Rosas’ Organised by Gibraltar Cultural Services John Mackintosh Hall Theatre Tickets £5 from the John Mackintosh Hall as from Tuesday 23rd April between 9am and 4pm For further information please contact telephone 20067236 or email: [email protected] Saturday -

GHA Board Report – July 2019-September 2019

GHA Board Report – July 2019-September 2019 GHA BOARD MEETING AGENDA Venue: Charles Hunt Room, John Mackintosh Hall Wednesday 17th June 2020 at 11.00hrs 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of the meeting held on 31st July 2019 3. Matters arising 4. Statement by the Minister for Health 5. Matters for the report 5.1 Report: Medical Director and Executive Summary 5.2 Report: Director of Public Health 5.3 Report: Head of Estates and Clinical Engineering 5.4 Report: Director of Nursing Services 5.5 Report: Human Resources Manager 5.6 Report: Hospital Services – General Manager 5.7 Report: Primary Care Services – Deputy Medical Director 5.8 Report: Mental Health – General Manager 5.9 Report: Director of Information Management and Technology 5.10 Report: School of Health Studies 6. Date and time of next meeting 7. In-Camera session 1 GHA Board Report – July 2019-September 2019 2 GHA Board Report – July 2019-September 2019 5.1 Executive Summary – Medical Director Please see 2019 Quarter 4 Board Report for Executive Summary 3 GHA Board Report – July 2019-September 2019 5.2 Director of Public Health This has been a busy time, despite the fact that summer is traditionally quiet. The Island Games created both opportunities and pressures on resources but has helped us continue to develop good relationships across many sectors. The hospital remains a focus of intense activity in terms of infection control. A Hospital is a safe environment for sick people, and therefore they should be protected from infections that could be prevented. Activities of the Health Promotion Department July – September 2019 Main Public Health Events of this Quarter Building Health & Wellbeing data Sun Safety at Gibraltar Calling Music Festival Mental Health Campaign Public Events .