The Construction of Gibraltarian Identity in MG

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish Jonathan Roig Advisor: Jason Shaw Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract Dialect perception studies have revealed that speakers tend to have false biases about their own dialect. I tested that claim with Puerto Rican Spanish speakers: do they perceive their dialect as a standard or non-standard one? To test this question, based on the dialect perception work of Niedzielski (1999), I created a survey in which speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish listen to sentences with a phonological phenomenon specific to their dialect, in this case a syllable- final substitution of [R] with [l]. They then must match the sounds they hear in each sentence to one on a six-point continuum spanning from [R] to [l]. One-third of participants are told that they are listening to a Puerto Rican Spanish speaker, one-third that they are listening to a speaker of Standard Spanish, and one-third are told nothing about the speaker. When asked to identify the sounds they hear, will participants choose sounds that are more similar to Puerto Rican Spanish or more similar to the standard variant? I predicted that Puerto Rican Spanish speakers would identify sounds as less standard when told the speaker was Puerto Rican, and more standard when told that the speaker is a Standard Spanish speaker, despite the fact that the speaker is the same Puerto Rican Spanish speaker in all scenarios. Some effect can be found when looking at differences by age and household income, but the results of the main effect were insignificant (p = 0.680) and were therefore inconclusive. -

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

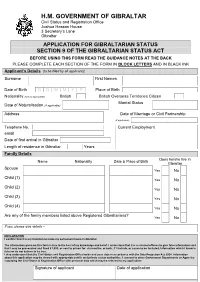

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

Excursion from Puerto Banús to Gibraltar by Jet

EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR BY JET SKI EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR Marbella Jet Center is pleased to present you an exciting excursion to discover Gibraltar. We propose a guided historical tour on a jet ski, along the historic and picturesque coast of Gibraltar, aimed at any jet ski lover interested in visiting Gibraltar. ENVIRONMENT Those who love jet skis who want to get away from the traffic or prefer an educational and stimulating experience can now enjoy a guided tour of the Gibraltar Coast, as is common in many Caribbean destinations. Historic, unspoiled and unadorned, what better way to see Gibraltar's mighty coastline than on a jet ski. YOUR EXPERIENCE When you arrive in Gibraltar, you will be taken to a meeting point in “Marina Bay” and after that you will be accompanied to the area where a briefing will take place in which you will be explained the safety rules to follow. GIBRALTAR Start & Finish at Marina Bay Snorkelling Rosia Bay Governor’s Beach & Gorham’s Cave Light House & Southern Defenses GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI After the safety brief: Later peoples, notably the Moors and the Spanish, also established settlements on Bay of Gibraltar the shoreline during the Middle Ages and early modern period, including the Heading out to the center of the bay, tourists may have a chance to heavily fortified and highly strategic port at Gibraltar, which fell to England in spot the local pods of dolphins; they can also have a group photograph 1704. -

Coarticulation Between Aspirated-S and Voiceless Stops in Spanish: an Interdialectal Comparison

Coarticulation between Aspirated-s and Voiceless Stops in Spanish: An Interdialectal Comparison Francisco Torreira University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction In a large number of Spanish dialects, representing many of the world’s Spanish speakers, /s/ is reduced to or deleted entirely in word-internal preconsonantal position (e.g. /este/ → [ehte], este ‘this’), in word-final preconsonantal position (e.g. /las#toman/ → [lahtoman], las toman ‘they take them’), and/or in prepausal position (e.g. /komemos/ → [komemo(h)], comemos ‘we eat’). In those dialects considered the most phonologically innovative (such as the Spanish of Andalusia, Extremadura, Canary Islands, Hispanic Caribbean, Pacific coast of South America), /s/ debuccalization is also found in prevocalic environments word-finally (e.g. /las#alas/ → [lahala], las alas ‘the wings’) and even word-internally, this phenomenon being less common (e.g. /asi/ → [ahi], así ‘this way’). When considered in detail, the manifestations of aspirated-s can be very different depending on dialectal, phonetic and even sociolinguistic factors. Only in preconsonantal position, for example, different s-apirating dialects behave differently; and, even within each dialect and in preconsonantal position, different manifestations arise as a result of the consonant type following aspirated-s. In this study, I show that aspirated-s before voiceless stops has different phonetic characteristics in Western Andalusian, on one part, and Puerto Rican and Porteño Spanish on the other. While Western Andalusian exhibits consistent postaspiration and shorter or inexistent preaspiration, Puerto Rican and Porteño display consistent preaspiration but no postaspiration. Moreover, Andalusian Spanish voiceless stops in /hC/ clusters show a longer closure than voiceless stops in other conditions, a contrast that does not apply for Porteño and Puerto Rican Spanish. -

Download This Report

Report GIBRALTAR A ROCK AND A HARDWARE PLACE As one of the four island iGaming hubs in Europe, Gibraltar’s tiny 6.8sq.km leaves a huge footprint in the gaming sector Gibraltar has long been associated with Today, Gibraltar is self-governing and for duty free cigarettes, booze and cheap the last 25 years has also been electrical goods, the wild Barbary economically self sufficient, although monkeys, border crossing traffic jams, the some powers such as the defence and Rock and online gaming. foreign relations remain the responsibility of the UK government. It is a key base for It’s an odd little territory which seems to the British Royal Navy due to its strategic continually hover between its Spanish location. and British roots and being only 6.8sq.km in size, it is crammed with almost 30,000 During World War II the area was Gibraltarians who have made this unique evacuated and the Rock was strengthened zone their home. as a fortress. After the 1968 referendum Spain severed its communication links Gibraltar is a British overseas peninsular that is located on the southern tip of Spain overlooking the African coastline as GIBRALTAR IS A the Atlantic Ocean meets the POPULAR PORT Mediterranean and the English meet the Spanish. Its position has caused a FOR TOURIST continuous struggle for power over the CRUISE SHIPS AND years particularly between Spain and the British who each want to control this ALSO ATTRACTS unique territory, which stands guard over the western Mediterranean via the Straits MANY VISITORS of Gibraltar. FROM SPAIN FOR Once ruled by Rome the area fell to the DAY VISITS EAGER Goths then the Moors. -

Thursday 23Rd January 2020

P R O C E E D I N G S O F T H E G I B R A L T A R P A R L I A M E N T AFTERNOON SESSION: 3.15 p.m. – 6.45 p.m. Gibraltar, Thursday, 23rd January 2020 Contents Questions for Oral Answer ..................................................................................................... 3 Economic Development, Enterprise, Telecommunications and the GSB......................................... 3 Q92-96/2020 Public finances – GSB legal right of set off; Consolidated Fund and Improvement & Development Fund outturn; Credit Finance debentures; RBSI credit facility agreement ................................................................................................................................ 3 Q97-98/2020 Employment for disabled individuals – Numbers in various schemes ............... 7 Q98-99/2020 NVQ Levels 1 to 4 – Numbers qualified by trade and year .............................. 11 Standing Order 7(1) suspended to proceed with Government Statement ............................ 15 Rise in Import Duty on cigarettes – Statement by the Chief Minister ................................... 15 Standing Order 7(1) suspended to proceed with questions ................................................... 16 Chief Minister ................................................................................................................................. 16 Q100-01/2020 Civil Service sick leave – Rate by Department; mental health issues ............ 16 Q102-103/2020 Chief Minister’s New Year message – Dealing with abuses; strengthening public finances -

Heritage Month

HARRIS BEACH RECOGNIZES NATIONAL HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH National Hispanic Heritage Month in the United States honors the histories, cultures and contributions of American citizens whose ancestors came from Spain, Mexico, the Caribbean and Central and South America. We’re participating at Harris Beach by spotlighting interesting Hispanic public figures, and facts about different countries, and testing your language skills. As our focus on National Hispanic Heritage Month continues, this week we focus on a figure from the world of sports: Roberto Clemente, who is known as much for his accomplishments as humanitarian as he is for his feats on the field of play. ROBERTO CLEMENTE Roberto Enrique Clemente Walker of Puerto Rico, born August 18, 1934, has the distinction of being the first Latin American and Caribbean player to be inducted in the National Baseball Hall of Fame. He played right field over 18 seasons for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Clemente’s untimely death established the precedent that, as an alternative to the five-year retirement period, a player who has been deceased for at least six months is eligible for entry into the Hall of Fame. Clemente was the youngest of 7 children and was raised in Barrio San Antón, Carolina, Puerto Rico. During his childhood, his father worked as foreman of sugar crops located in the municipality and, because the family’s resources were limited, Clemente worked alongside his father in the fields by loading and unloading trucks. Clemente was a track and field star and Olympic hopeful before deciding to turn his full attention to baseball. His interest in baseball showed itself early on in childhood with Clemente often times playing against neighboring barrios. -

Infogibraltar Servicio De Información De Gibraltar

InfoGibraltar Servicio de Información de Gibraltar Comunicado Gobierno de Gibraltar: Ministerio de Deportes, Cultura, Patrimonio y Juventud Comedia Llanita de la Semana Nacional Gibraltar, 21 de julio de 2014 El Ministerio de Cultura se complace en anunciar los detalles de la Comedia Yanita de la Semana Nacional (National Week) de este año, la cual se representará entre el lunes 1 de septiembre y el viernes 5 de septiembre de 2014. La empresa Santos Productions, responsable de organizar el evento, está muy satisfecha de presentar ‘To be Llanito’ (Ser llanito), una comedia escrita y dirigida por Christian Santos. La producción será representada en el Teatro de John Mackintosh Hall, y las actuaciones darán comienzo a las 20 h. Las entradas tendrán un precio de 12 libras y se pondrán a la venta a partir del 13 de agosto en the Nature Shop en La Explanada (Casemates Square). Para más información, contactar con Santos Productions mediante el e‐mail: info@santos‐ productions.com Nota a redactores: Esta es una traducción realizada por la Oficina de Información de Gibraltar. Algunas palabras no se encuentran en el documento original y se han añadido para mejorar el sentido de la traducción. El texto válido es el original en inglés. Para cualquier ampliación de esta información, rogamos contacte con Oficina de Información de Gibraltar Miguel Vermehren, Madrid, [email protected], Tel 609 004 166 Sandra Balvín, Campo de Gibraltar, [email protected], Tel 661 547 573 Web: www.infogibraltar.com, web en inglés: www.gibraltar.gov.gi/press‐office Twitter: @infogibraltar 21/07/2014 1/2 HM GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR MINISTRY FOR SPORTS, CULTURE, HERITAGE & YOUTH 310 Main Street Gibraltar PRESS RELEASE No: 385/2014 Date: 21st July 2014 GIBRALTAR NATIONAL WEEK YANITO COMEDY The Ministry of Culture is pleased to announce the details for this year’s National Week Yanito Comedy, which will be held from Monday 1st September to Friday 5th September 2014. -

United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit

United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit Nos. 12-2364, 12-2367 UNITED STATES, Appellee, v. WENDELL RIVERA-RUPERTO, a/k/a Arsenio Rivera, Defendant, Appellant. APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF PUERTO RICO [Hon. Juan M. Pérez-Giménez, U.S. District Judge] Before Torruella, Lipez, and Thompson, Circuit Judges. H. Manuel Hernández for appellant. Robert J. Heberle, Attorney, Public Integrity Section, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice, with whom Francisco A. Besosa-Martínez, Assistant United States Attorney, Nelson Pérez-Sosa, Assistant United States Attorney, Chief, Appellate Division, and Rosa Emilia Rodríguez-Vélez, United States Attorney, were on brief, for appellee. January 13, 2017 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. This case arises out of a now- familiar, large-scale FBI investigation known as "Operation Guard Shack," in which the FBI, in an effort to root out police corruption throughout Puerto Rico, orchestrated a series of staged drug deals over the course of several years.1 For his participation in six of these Operation Guard Shack drug deals, Defendant- Appellant Wendell Rivera-Ruperto stood two trials and was found guilty of various federal drug and firearms-related crimes. The convictions resulted in Rivera-Ruperto receiving a combined sentence of 161-years and 10-months' imprisonment. Although Rivera-Ruperto raises similar challenges in his appeals from the two separate trials, each trial was presided over by a different district judge. Thus, there are two cases on appeal, and we address the various challenges today in separate opinions.2 In this present appeal from the first trial, Rivera- Ruperto argues that the district court committed reversible errors when it: (1) denied his claim for ineffective assistance of counsel during the plea-bargaining stage; (2) failed to instruct the jury that it was required to find drug quantity beyond a reasonable 1 See, e.g., United States v. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE No: 756/2015 Date: 21st October 2015 Gibraltar authors bring Calpean zest to Literary Festival events As the date for the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival draws closer, the organisers have released more details of the local authors participating in the present edition. The confirmed names are Adolfo Canepa, Richard Garcia, Mary Chiappe & Sam Benady and Humbert Hernandez. Former AACR Chief Minister Adolfo Canepa was Sir Joshua Hassan’s right-hand man for many years. Currently Speaker and Mayor of the Gibraltar Parliament, Mr Canepa recently published his memoirs ‘Serving My Gibraltar,’ where he gives a candid account of his illustrious and extensive political career. Interestingly, Mr Canepa, who was first elected to the Rock’s House of Assembly in 1972, has held all the major public offices in Gibraltar, including that of Leader of the Opposition. Richard Garcia, a retired teacher, senior Civil Servant and former Chief Secretary, is no stranger to the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival. He has written numerous books in recent years delving into the Rock's social history including the evolution of local commerce. An internationally recognised philatelist, Mr Garcia will be presenting his latest work commemorating the 50th anniversary of the event’s main sponsor, the Gibunco Group, and the Bassadone family history since 1737. Mary Chiappe, half of the successful writing tandem behind the locally flavoured detective series ‘The Bresciano Mysteries’ – the other half being Sam Benady – returns to the festival with her literary associate to delight audiences with the suggestively titled ‘The Dead Can’t Paint’, seventh and final instalment of their detective series. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind.