An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 1

Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 1 Condominiums And Shared Sovereignty Abstract As the United Kingdom (UK) voted to leave the European Union (EU), the future of Gibraltar, appears to be in peril. Like Northern Ireland, Gibraltar borders with EU territory and strongly relies on its ties with Spain for its economic stability, transports and energy supplies. Although the Gibraltarian government is struggling to preserve both its autonomy with British sovereignty and accession to the European Union, the Spanish government states that only a form of joint- sovereignty would save Gibraltar from the same destiny as the rest of UK in case of complete withdrawal from the EU, without any accession to the European Economic Area (Hard Brexit). The purpose of this paper is to present the concept of Condominium as a federal political system based on joint-sovereignty and, by presenting the existing case of Condominiums (i.e. Andorra). The paper will assess if there are margins for applying a Condominium solution to Gibraltar. Condominiums and Shared Sovereignty | 2 Condominium in History and Political Theory The Latin word condominium comes from the union of the Latin prefix con (from cum, with) and the word dominium (rule). Watts (2008: 11) mentioned condominiums among one of the forms of federal political systems. As the word suggests, it is a form of shared sovereignty involving two or more external parts exercising a joint form of sovereignty over the same area, sometimes in the form of direct control, and sometimes while conceding or maintaining forms of self-government on the subject area, occasionally in a relationship of suzerainty (Shepheard, 1899). -

Political Change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies. Cuthbert J

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1973 From crown colony to associate statehood : political change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies. Cuthbert J. Thomas University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Thomas, Cuthbert J., "From crown colony to associate statehood : political change in Dominica, the Commonwealth West Indies." (1973). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1879. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1879 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ^^^^^^^ ^0 ASSOCIATE STATEHOOD: CHANGE POLITICAL IN DOMINICA, THE COMMONWEALTH WEST INDIES A Dissertation Presented By CUTHBERT J. THOMAS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 1973 Major Subject Political Science C\ithbert J. Thomas 1973 All Rights Reserved FROM CROV/N COLONY TO ASSOCIATE STATEHOOD: POLITICAL CHANGE IN DOMINICA, THE COMMONWEALTH WEST INDIES A Dissertation By CUTHBERT J. THOMAS Approved as to stylq and content by; Dr. Harvey "T. Kline (Chairman of Committee) Dr. Glen Gorden (Head of Department) Dr» Gerard Braunthal^ (Member) C 1 Dro George E. Urch (Member) May 1973 To the Youth of Dominica who wi3.1 replace these colonials before long PREFACE My interest in Comparative Government dates back to ray days at McMaster University during the 1969-1970 academic year. -

Hearing on the Report of the Chief Justice of Gibraltar

[2009] UKPC 43 Privy Council No 0016 of 2009 HEARING ON THE REPORT OF THE CHIEF JUSTICE OF GIBRALTAR REFERRAL UNDER SECTION 4 OF THE JUDICIAL COMMITTEE ACT 1833 before Lord Phillips Lord Hope Lord Rodger Lady Hale Lord Brown Lord Judge Lord Clarke ADVICE DELIVERED ON 12 November 2009 Heard on 15,16, 17, and 18 June 2009 Chief Justice of Gibraltar Governor of Gibraltar Michael Beloff QC Timothy Otty QC Paul Stanley (Instructed by Clifford (Instructed by Charles Chance LLP) Gomez & Co and Carter Ruck) Government of Gibraltar James Eadie QC (Instructed by R J M Garcia) LORD PHILLIPS : 1. The task of the Committee is to advise Her Majesty whether The Hon. Mr Justice Schofield, Chief Justice of Gibraltar, should be removed from office by reason of inability to discharge the functions of his office or for misbehaviour. The independence of the judiciary requires that a judge should never be removed without good cause and that the question of removal be determined by an appropriate independent and impartial tribunal. This principle applies with particular force where the judge in question is a Chief Justice. In this case the latter requirement has been abundantly satisfied both by the composition of the Tribunal that conducted the initial enquiry into the relevant facts and by the composition of this Committee. This is the advice of the majority of the Committee, namely, Lord Phillips, Lord Brown, Lord Judge and Lord Clarke. Security of tenure of judicial office under the Constitution 2. Gibraltar has two senior judges, the Chief Justice and a second Puisne Judge. -

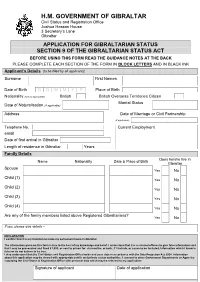

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

6 November 2008

Volume 13, Issue 45 - 6 November 2008 Rapid communications Measles outbreak in Gibraltar, August–October 2008 – a preliminary report 2 by V Kumar Emergence of fox rabies in north-eastern Italy 5 by P De Benedictis, T Gallo, A Iob, R Coassin, G Squecco, G Ferri, F D’Ancona, S Marangon, I Capua, F Mutinelli West Nile virus infections in Hungary, August–September 2008 7 by K Krisztalovics, E Ferenczi, Z Molnár, Á Csohán, E Bán, V Zöldi, K Kaszás A case of ciguatera fish poisoning in a French traveler 10 by M Develoux, G Le Loup, G Pialoux Invasive meningococcal disease with fatal outcome in a Swiss student visiting Berlin 12 by I Zuschneid, A Witschi, L Quaback, W Hellenbrand, N Kleinkauf, D Koch, G Krause Surveillance and outbreak reports A swimming pool-associated outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in Staffordshire, England, October to December 2007 14 by N Coetzee, O Edeghere, JM Orendi, R Chalmers, L Morgan Research articles The burden of genital warts in Slovenia: results from a national probability sample survey 17 by I Klavs, M Grgič-Vitek Perspectives Developing the Community reporting system for foodborne outbreaks 21 by A Gervelmeyer, M Hempen, U Nebel, C Weber, S Bronzwaer, A Ammon, P Makela EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR DISEASE PREVENTION AND CONTROL of writing this report, occasional cases were still coming in. Prior time the At measles. of cases diagnosed clinically 276 of notified 31 October 2008, the Gibraltar Public Health Department was Europe andgoodstandardsofpublichygiene. Western with par on indicators health with nation affluent generally the spread of some infectious diseases. -

Excursion from Puerto Banús to Gibraltar by Jet

EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR BY JET SKI EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR Marbella Jet Center is pleased to present you an exciting excursion to discover Gibraltar. We propose a guided historical tour on a jet ski, along the historic and picturesque coast of Gibraltar, aimed at any jet ski lover interested in visiting Gibraltar. ENVIRONMENT Those who love jet skis who want to get away from the traffic or prefer an educational and stimulating experience can now enjoy a guided tour of the Gibraltar Coast, as is common in many Caribbean destinations. Historic, unspoiled and unadorned, what better way to see Gibraltar's mighty coastline than on a jet ski. YOUR EXPERIENCE When you arrive in Gibraltar, you will be taken to a meeting point in “Marina Bay” and after that you will be accompanied to the area where a briefing will take place in which you will be explained the safety rules to follow. GIBRALTAR Start & Finish at Marina Bay Snorkelling Rosia Bay Governor’s Beach & Gorham’s Cave Light House & Southern Defenses GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI After the safety brief: Later peoples, notably the Moors and the Spanish, also established settlements on Bay of Gibraltar the shoreline during the Middle Ages and early modern period, including the Heading out to the center of the bay, tourists may have a chance to heavily fortified and highly strategic port at Gibraltar, which fell to England in spot the local pods of dolphins; they can also have a group photograph 1704. -

In This Issue Upcoming Events Revolutionary War Battles in June

Official Publication of the WA State, Alexander Hamilton Chapter, SAR Volume V, Issue 6 (June 2019) Editor Dick Motz In This Issue Upcoming Events Revolutionary War Battles in June .................. 2 Alexander Hamilton Trivia? ............................ 2 Message from the President ........................... 2 What is the SAR? ............................................ 3 Reminders ..................................................... 3 Do you Fly? .................................................... 3 June Birthdays ............................................... 4 Northern Region Meeting Activities & Highlights ....................... 4 Chapter Web Site ........................................... 5 20 July: West Seattle Parade Member Directory Update ............................. 5 Location: West Seattle (Map Link). Wanted/For Sale ............................................ 6 Southern Region Battles of the Revolutionary War Map ............ 6 4 July: Independence Day Parade Location: Steilacoom (Map Link). Plan ahead for these Special Dates in July 17 Aug: Woodinville Parade 4 Jul: Independence Day Location: Woodinville (Map Link) 6 Jul: International Kissing Day 6 Jul: National fried Chicken Day 2 Sep: Labor Day Parade (pending) 17 Jul: National Tattoo Day Location: Black Diamond (Map Link) 29 Jul: National Chicken Wing Day 15-16 Sep: WA State Fair Booth Location: Puyallup 21 Sep: Chapter meeting Johnny’s at Fife, 9:00 AM. 9 Nov: Veterans Day Parade Location: Auburn (Map Link) 14 Dec: Wreaths Across America Location: JBLM (Map -

Anguilla: a Tourism Success Story?

Visions in Leisure and Business Volume 14 Number 4 Article 4 1996 Anguilla: A Tourism Success Story? Paul F. Wilkinson York University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions Recommended Citation Wilkinson, Paul F. (1996) "Anguilla: A Tourism Success Story?," Visions in Leisure and Business: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions/vol14/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visions in Leisure and Business by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ANGUILLA: A TOURISM SUCCESS STORY? BY DR. PAUL F. WILKINSON, PROFESSOR FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY 4700KEELE STREET NORTH YORK, ONTARIO CANADA MJJ 1P3 ABSTRACT More than any other Caribbean community, the Anguillans [sic )1 have Anguilla is a Caribbean island microstate the sense of home. The land has been that has undergone dramatic tourism growth, theirs immemorially; no humiliation passing through the early stages of Butler's attaches to it. There are no Great tourist cycle model to the "development" houses2 ; there arenot even ruins. (32) stage. This pattern is related to deliberate government policy and planning decisions, including a policy of not having a limit to INTRODUCTION tourism growth. The resulting economic dependence on tourism has led to positive Anguilla is a Caribbean island microstate economic benefits (e.g., high GDP per that has undergone dramatic tourism growth, capita, low unemployment, and significant passing through the early stages of Butler's localinvolvement in the industry). (3) tourist cycle model to the "development" stage. -

UK Overseas Territories

INFORMATION PAPER United Kingdom Overseas Territories - Toponymic Information United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), also known as British Overseas Territories (BOTs), have constitutional and historical links with the United Kingdom, but do not form part of the United Kingdom itself. The Queen is the Head of State of all the UKOTs, and she is represented by a Governor or Commissioner (apart from the UK Sovereign Base Areas that are administered by MOD). Each Territory has its own Constitution, its own Government and its own local laws. The 14 territories are: Anguilla; Bermuda; British Antarctic Territory (BAT); British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT); British Virgin Islands; Cayman Islands; Falkland Islands; Gibraltar; Montserrat; Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands; Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha; South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands; Turks and Caicos Islands; UK Sovereign Base Areas. PCGN recommend the term ‘British Overseas Territory Capital’ for the administrative centres of UKOTs. Production of mapping over the UKOTs does not take place systematically in the UK. Maps produced by the relevant territory, preferably by official bodies such as the local government or tourism authority, should be used for current geographical names. National government websites could also be used as an additional reference. Additionally, FCDO and MOD briefing maps may be used as a source for names in UKOTs. See the FCDO White Paper for more information about the UKOTs. ANGUILLA The territory, situated in the Caribbean, consists of the main island of Anguilla plus some smaller, mostly uninhabited islands. It is separated from the island of Saint Martin (split between Saint-Martin (France) and Sint Maarten (Netherlands)), 17km to the south, by the Anguilla Channel. -

Gibraltar Harbour Bernard Bonfiglio Meng Ceng MICE 1, Doug Cresswell Msc2, Dr Darren Fa Phd3, Dr Geraldine Finlayson Phd3, Christopher Tovell Ieng MICE4

Bernard Bonfiglio, Doug Cresswell, Dr Darren Fa, Dr Geraldine Finlayson, Christopher Tovell Gibraltar Harbour Bernard Bonfiglio MEng CEng MICE 1, Doug Cresswell MSc2, Dr Darren Fa PhD3, Dr Geraldine Finlayson PhD3, Christopher Tovell IEng MICE4 1 CASE Consultants Civil and Structural Engineers, Torquay, United Kingdom, 2 HR Wallingford, Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 8BA, UK 3 Gibraltar Museum, Gibraltar 4 Ramboll (Gibraltar) Ltd, Gibraltar Presented at the ICE Coasts, Marine Structures and Breakwaters conference, Edinburgh, September 2013 Introduction The Port of Gibraltar lies on a narrow five kilometer long peninsula on Spain’s south eastern Mediterranean coast. Gibraltar became British in 1704 and is a self-governing territory of the United Kingdom which covers 6.5 square kilometers, including the port and harbour. It is believed that Gibraltar has been used as a harbour by seafarers for thousands of years with evidence dating back at least three millennia to Phoenician times; however up until the late 19th Century it provided little shelter for vessels. Refer to Figure 1 which shows the coast line along the western side of Gibraltar with the first structure known as the ‘Old Mole’ on the northern end of the town. Refer to figure 1 below. Location of the ‘Old Mole’ N The Old Mole as 1770 Figure 1 Showing the harbour with the first harbour structure, the ‘Old Mole’ and the structure in detail as in 1770. The Old Mole image has been kindly reproduced with permission from the Gibraltar Museum. HRPP577 1 Bernard Bonfiglio, Doug Cresswell, Dr Darren Fa, Dr Geraldine Finlayson, Christopher Tovell The modern Port of Gibraltar occupies a uniquely important strategic location, demonstrated by the many naval battles fought at and for the peninsula. -

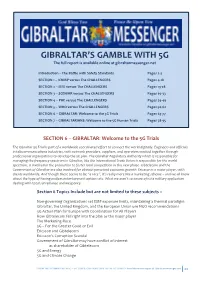

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but