Multiculturalism in the Creation of a Gibraltarian Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

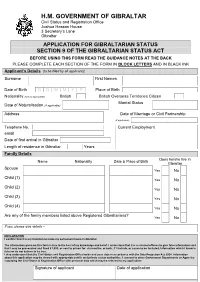

Application for Gibraltarian Status (Section 9)

H.M. GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR Civil Status and Registration Office Joshua Hassan House 3 Secretary’s Lane Gibraltar APPLICATION FOR GIBRALTARIAN STATUS SECTION 9 OF THE GIBRALTARIAN STATUS ACT BEFORE USING THIS FORM READ THE GUIDANCE NOTES AT THE BACK PLEASE COMPLETE EACH SECTION OF THE FORM IN BLOCK LETTERS AND IN BLACK INK Applicant’s Details (to be filled by all applicants) Surname First Names Date of Birth D D M M Y Y Place of Birth Nationality (tick as appropriate) British British Overseas Territories Citizen Marital Status Date of Naturalisation (if applicable) Address Date of Marriage or Civil Partnership (if applicable) Telephone No. Current Employment email Date of first arrival in Gibraltar Length of residence in Gibraltar Years Family Details Does he/she live in Name Nationality Date & Place of Birth Gibraltar Spouse Yes No Child (1) Yes No Child (2) Yes No Child (3) Yes No Child (4) Yes No Are any of the family members listed above Registered Gibraltarians? Yes No If yes, please give details – DECLARATION I confirm that it is my intention to make my permanent home in Gibraltar. The information given on this form is true to the best of my knowledge and belief. I understand that it is a criminal offence to give false information and that I may be prosecuted and fined £1,000, or sent to prison for six months, or both, if I include, or cause to be included, information which I know is false or do not believe to be true. I also understand that the Civil Status and Registration Office holds and uses data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2004. -

Excursion from Puerto Banús to Gibraltar by Jet

EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR BY JET SKI EXCURSION FROM PUERTO BANÚS TO GIBRALTAR Marbella Jet Center is pleased to present you an exciting excursion to discover Gibraltar. We propose a guided historical tour on a jet ski, along the historic and picturesque coast of Gibraltar, aimed at any jet ski lover interested in visiting Gibraltar. ENVIRONMENT Those who love jet skis who want to get away from the traffic or prefer an educational and stimulating experience can now enjoy a guided tour of the Gibraltar Coast, as is common in many Caribbean destinations. Historic, unspoiled and unadorned, what better way to see Gibraltar's mighty coastline than on a jet ski. YOUR EXPERIENCE When you arrive in Gibraltar, you will be taken to a meeting point in “Marina Bay” and after that you will be accompanied to the area where a briefing will take place in which you will be explained the safety rules to follow. GIBRALTAR Start & Finish at Marina Bay Snorkelling Rosia Bay Governor’s Beach & Gorham’s Cave Light House & Southern Defenses GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI GIBRALTAR HISTORICAL PLACES DURING THE 2-HOUR TOUR BY JET SKI After the safety brief: Later peoples, notably the Moors and the Spanish, also established settlements on Bay of Gibraltar the shoreline during the Middle Ages and early modern period, including the Heading out to the center of the bay, tourists may have a chance to heavily fortified and highly strategic port at Gibraltar, which fell to England in spot the local pods of dolphins; they can also have a group photograph 1704. -

Download This Report

Report GIBRALTAR A ROCK AND A HARDWARE PLACE As one of the four island iGaming hubs in Europe, Gibraltar’s tiny 6.8sq.km leaves a huge footprint in the gaming sector Gibraltar has long been associated with Today, Gibraltar is self-governing and for duty free cigarettes, booze and cheap the last 25 years has also been electrical goods, the wild Barbary economically self sufficient, although monkeys, border crossing traffic jams, the some powers such as the defence and Rock and online gaming. foreign relations remain the responsibility of the UK government. It is a key base for It’s an odd little territory which seems to the British Royal Navy due to its strategic continually hover between its Spanish location. and British roots and being only 6.8sq.km in size, it is crammed with almost 30,000 During World War II the area was Gibraltarians who have made this unique evacuated and the Rock was strengthened zone their home. as a fortress. After the 1968 referendum Spain severed its communication links Gibraltar is a British overseas peninsular that is located on the southern tip of Spain overlooking the African coastline as GIBRALTAR IS A the Atlantic Ocean meets the POPULAR PORT Mediterranean and the English meet the Spanish. Its position has caused a FOR TOURIST continuous struggle for power over the CRUISE SHIPS AND years particularly between Spain and the British who each want to control this ALSO ATTRACTS unique territory, which stands guard over the western Mediterranean via the Straits MANY VISITORS of Gibraltar. FROM SPAIN FOR Once ruled by Rome the area fell to the DAY VISITS EAGER Goths then the Moors. -

An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar

.............................................................................................................................................................................................................WORK IN PROGESS WORK IN PROGRESS TOMASZ PACIORKOWSKI DOI: 10.15290/CR.2018.23.4.05 Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań An Overlooked Colonial English of Europe: the Case of Gibraltar Abstract. Gibraltar, popularly known as “The Rock”, has been a British overseas territory since the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1713. The demographics of this unique colony reflect its turbulent past, with most of the population being of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian origin (Garcia 1994). Additionally, there are prominent minorities of Indians, Maltese, Moroccans and Jews, who have also continued to influence both the culture and the languages spoken in Gibraltar (Kellermann 2001). Despite its status as the only English overseas territory in continental Europe, Gibraltar has so far remained relatively neglected by scholars of sociolinguistics, new dialect formation, and World Englishes. The paper provides a summary of the current state of sociolinguistic research in Gibraltar, focusing on such aspects as identity formation, code-switching, language awareness, language attitudes, and norms. It also delineates a plan for further research on code-switching and national identity following the 2016 Brexit referendum. Keywords: Gibraltar, code-switching, sociolinguistics, New Englishes, dialect formation, Brexit. 1. Introduction Gibraltar is located on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula and measures just about 6 square kilometres. This small size, however, belies an extraordinarily complex political history and social fabric. In the Brexit referendum of 23rd of June 2016, the inhabitants of Gibraltar overwhelmingly expressed their willingness to continue belonging to the European Union, yet at the moment it appears that they will be forced to follow the decision of the British govern- ment and leave the EU (Garcia 2016). -

Gibraltar's Constitutional Future

RESEARCH PAPER 02/37 Gibraltar’s Constitutional 22 MAY 2002 Future “Our aims remain to agree proposals covering all outstanding issues, including those of co-operation and sovereignty. The guiding principle of those proposals is to build a secure, stable and prosperous future for Gibraltar and a modern sustainable status consistent with British and Spanish membership of the European Union and NATO. The proposals will rest on four important pillars: safeguarding Gibraltar's way of life; measures of practical co-operation underpinned by economic assistance to secure normalisation of relations with Spain and the EU; extended self-government; and sovereignty”. Peter Hain, HC Deb, 31 January 2002, c.137WH. In July 2001 the British and Spanish Governments embarked on a new round of negotiations under the auspices of the Brussels Process to resolve the sovereignty dispute over Gibraltar. They aim to reach agreement on all unresolved issues by the summer of 2002. The results will be put to a referendum in Gibraltar. The Government of Gibraltar has objected to the process and has rejected any arrangement involving shared sovereignty between Britain and Spain. Gibraltar is pressing for the right of self-determination with regard to its constitutional future. The Brussels Process covers a wide range of topics for discussion. This paper looks primarily at the sovereignty debate. It also considers how the Gibraltar issue has been dealt with at the United Nations. Vaughne Miller INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS AND DEFENCE SECTION HOUSE OF COMMONS LIBRARY Recent Library Research Papers include: List of 15 most recent RPs 02/22 Social Indicators 10.04.02 02/23 The Patents Act 1977 (Amendment) (No. -

Thesis.Pdf (PDF, 297.83KB)

Cover Illustrations by the Author after two drawings by François Boucher. i Contents Note on Dates iii. Introduction 1. Chapter I - The Coming of the Dutchman: Prior’s Diplomatic Apprenticeship 7. Chapter II - ‘Mat’s Peace’, the betrayal of the Dutch, and the French friendship 17. Chapter III - The Treaty of Commerce and the Empire of Trade 33. Chapter IV - Matt, Harry, and the Idea of a Patriot King 47. Conclusion - ‘Britannia Rules the Waves’ – A seventy-year legacy 63. Bibliography 67. ii Note on Dates: The dates used in the following are those given in the sources from which each particular reference comes, and do not make any attempt to standardize on the basis of either the Old or New System. It should also be noted that whilst Englishmen used the Old System at home, it was common (and Matthew Prior is no exception) for them to use the New System when on the Continent. iii Introduction It is often the way with historical memory that the man seen by his contemporaries as an important powerbroker is remembered by posterity as little more than a minor figure. As is the case with many men of the late-Seventeenth- and early-Eighteenth-Centuries, Matthew Prior’s (1664-1721) is hardly a household name any longer. Yet in the minds of his contemporaries and in the political life of his country even after his death his importance was, and is, very clear. Since then he has been the subject of three full-length biographies, published in 1914, 1921, and 1939, all now out of print.1 Although of low birth Prior managed to attract the attention of wealthy patrons in both literary and diplomatic circles and was, despite his humble station, blessed with an education that was to be the foundation of his later success. -

Gibraltar Harbour Bernard Bonfiglio Meng Ceng MICE 1, Doug Cresswell Msc2, Dr Darren Fa Phd3, Dr Geraldine Finlayson Phd3, Christopher Tovell Ieng MICE4

Bernard Bonfiglio, Doug Cresswell, Dr Darren Fa, Dr Geraldine Finlayson, Christopher Tovell Gibraltar Harbour Bernard Bonfiglio MEng CEng MICE 1, Doug Cresswell MSc2, Dr Darren Fa PhD3, Dr Geraldine Finlayson PhD3, Christopher Tovell IEng MICE4 1 CASE Consultants Civil and Structural Engineers, Torquay, United Kingdom, 2 HR Wallingford, Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX10 8BA, UK 3 Gibraltar Museum, Gibraltar 4 Ramboll (Gibraltar) Ltd, Gibraltar Presented at the ICE Coasts, Marine Structures and Breakwaters conference, Edinburgh, September 2013 Introduction The Port of Gibraltar lies on a narrow five kilometer long peninsula on Spain’s south eastern Mediterranean coast. Gibraltar became British in 1704 and is a self-governing territory of the United Kingdom which covers 6.5 square kilometers, including the port and harbour. It is believed that Gibraltar has been used as a harbour by seafarers for thousands of years with evidence dating back at least three millennia to Phoenician times; however up until the late 19th Century it provided little shelter for vessels. Refer to Figure 1 which shows the coast line along the western side of Gibraltar with the first structure known as the ‘Old Mole’ on the northern end of the town. Refer to figure 1 below. Location of the ‘Old Mole’ N The Old Mole as 1770 Figure 1 Showing the harbour with the first harbour structure, the ‘Old Mole’ and the structure in detail as in 1770. The Old Mole image has been kindly reproduced with permission from the Gibraltar Museum. HRPP577 1 Bernard Bonfiglio, Doug Cresswell, Dr Darren Fa, Dr Geraldine Finlayson, Christopher Tovell The modern Port of Gibraltar occupies a uniquely important strategic location, demonstrated by the many naval battles fought at and for the peninsula. -

THE CHIEF MINISTER's BUDGET ADDRESS 2017 Her Majesty's

Chief Minister’s Budget Address 2017 THE CHIEF MINISTER’S BUDGET ADDRESS 2017 Her Majesty’s Government of Gibraltar 6 Convent Place Gibraltar Mr Speaker I have the honour to move that the Bill now be read a second time. 2. INTRODUCTION 3. Mr Speaker, this is my sixth budget address as Chief Minister. 4. It is in fact my second budget address since our re-election to Government in November 2015 with a huge vote of confidence from our people, and I now have the honour to present the Government’s revenue and expenditure estimates for the financial year ending 31 st March 2018. 5. During the course of this address, I will also report to the House on the Government’s revenue and expenditure out-turn for the financial year ended 31 st March 2017, which was the fifth full year of a Socialist Liberal Administration since we took office on a warm autumn day in December 2011. 6. Mr Speaker, as has been traditional now for almost thirty years since the first GSLP Chief Minister delivered the first GSLP Budget in 1988, my address will of course be NOT JUST my report to the House on the Public Finances of our nation and the state of the economy generally, but also a Parliamentary ‘State of the Nation’ review of the economic and political future facing Gibraltar. 7. There could be no better way, Mr Speaker for the GSLP to celebrate its fortieth anniversary than with the honour of a second GSLP Chief Minister delivering a Socialist Budget for Gibraltar. -

Infogibraltar Servicio De Información De Gibraltar

InfoGibraltar Servicio de Información de Gibraltar Comunicado Gobierno de Gibraltar: Ministerio de Deportes, Cultura, Patrimonio y Juventud Comedia Llanita de la Semana Nacional Gibraltar, 21 de julio de 2014 El Ministerio de Cultura se complace en anunciar los detalles de la Comedia Yanita de la Semana Nacional (National Week) de este año, la cual se representará entre el lunes 1 de septiembre y el viernes 5 de septiembre de 2014. La empresa Santos Productions, responsable de organizar el evento, está muy satisfecha de presentar ‘To be Llanito’ (Ser llanito), una comedia escrita y dirigida por Christian Santos. La producción será representada en el Teatro de John Mackintosh Hall, y las actuaciones darán comienzo a las 20 h. Las entradas tendrán un precio de 12 libras y se pondrán a la venta a partir del 13 de agosto en the Nature Shop en La Explanada (Casemates Square). Para más información, contactar con Santos Productions mediante el e‐mail: info@santos‐ productions.com Nota a redactores: Esta es una traducción realizada por la Oficina de Información de Gibraltar. Algunas palabras no se encuentran en el documento original y se han añadido para mejorar el sentido de la traducción. El texto válido es el original en inglés. Para cualquier ampliación de esta información, rogamos contacte con Oficina de Información de Gibraltar Miguel Vermehren, Madrid, [email protected], Tel 609 004 166 Sandra Balvín, Campo de Gibraltar, [email protected], Tel 661 547 573 Web: www.infogibraltar.com, web en inglés: www.gibraltar.gov.gi/press‐office Twitter: @infogibraltar 21/07/2014 1/2 HM GOVERNMENT OF GIBRALTAR MINISTRY FOR SPORTS, CULTURE, HERITAGE & YOUTH 310 Main Street Gibraltar PRESS RELEASE No: 385/2014 Date: 21st July 2014 GIBRALTAR NATIONAL WEEK YANITO COMEDY The Ministry of Culture is pleased to announce the details for this year’s National Week Yanito Comedy, which will be held from Monday 1st September to Friday 5th September 2014. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009

United Nations A/AC.109/2009/15 General Assembly Distr.: General 18 March 2009 Original: English Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples Gibraltar Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page I. General ....................................................................... 3 II. Constitutional, legal and political issues ............................................ 3 III. Budget ....................................................................... 5 IV. Economic conditions ............................................................ 5 A. General................................................................... 5 B. Trade .................................................................... 6 C. Banking and financial services ............................................... 6 D. Transportation, communications and utilities .................................... 7 E. Tourism .................................................................. 8 V. Social conditions ............................................................... 8 A. Labour ................................................................... 8 B. Human rights .............................................................. 9 C. Social security and welfare .................................................. 9 D. Public health .............................................................. 9 E. Education ................................................................ -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE No: 756/2015 Date: 21st October 2015 Gibraltar authors bring Calpean zest to Literary Festival events As the date for the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival draws closer, the organisers have released more details of the local authors participating in the present edition. The confirmed names are Adolfo Canepa, Richard Garcia, Mary Chiappe & Sam Benady and Humbert Hernandez. Former AACR Chief Minister Adolfo Canepa was Sir Joshua Hassan’s right-hand man for many years. Currently Speaker and Mayor of the Gibraltar Parliament, Mr Canepa recently published his memoirs ‘Serving My Gibraltar,’ where he gives a candid account of his illustrious and extensive political career. Interestingly, Mr Canepa, who was first elected to the Rock’s House of Assembly in 1972, has held all the major public offices in Gibraltar, including that of Leader of the Opposition. Richard Garcia, a retired teacher, senior Civil Servant and former Chief Secretary, is no stranger to the Gibunco Gibraltar Literary Festival. He has written numerous books in recent years delving into the Rock's social history including the evolution of local commerce. An internationally recognised philatelist, Mr Garcia will be presenting his latest work commemorating the 50th anniversary of the event’s main sponsor, the Gibunco Group, and the Bassadone family history since 1737. Mary Chiappe, half of the successful writing tandem behind the locally flavoured detective series ‘The Bresciano Mysteries’ – the other half being Sam Benady – returns to the festival with her literary associate to delight audiences with the suggestively titled ‘The Dead Can’t Paint’, seventh and final instalment of their detective series. -

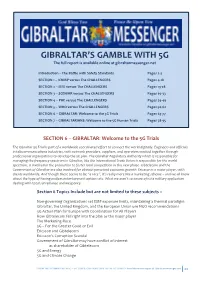

Gibraltar-Messenger.Net

GIBRALTAR’S GAMBLE WITH 5G The full report is available online at gibraltarmessenger.net Introduction – The Battle with Safety Standards Pages 2-3 SECTION 1 – ICNIRP versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 4-18 SECTION 2 – IEEE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 19-28 SECTION 3 – SCENIHR versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 29-33 SECTION 4 – PHE versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 34-49 SECTION 5 – WHO versus The CHALLENGERS Pages 50-62 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials Pages 63-77 SECTION 7 – GIBRALTARIANS: Welcome to the 5G Human Trials Pages 78-95 SECTION 6 – GIBRALTAR: Welcome to the 5G Trials The Gibraltar 5G Trial is part of a worldwide coordinated effort to connect the world digitally. Engineers and officials in telecommunications industries, with network providers, suppliers, and operators worked together through professional organizations to develop the 5G plan. The Gibraltar Regulatory Authority which is responsible for managing the frequency spectrum in Gibraltar, like the International Trade Union is responsible for the world spectrum, is involved in the promotion to foster local competition in this new phase. Gibtelecom and the Government of Gibraltar are also involved for obvious perceived economic growth. Ericsson is a major player, with clients worldwide. And though there seems to be “a race”, it’s really more like a marketing scheme – and we all know about the hype of having endless entertainment options etc. What we aren’t so aware of is its military application dealing with total surveillance and weaponry. Section 6 Topics Include but