Tragedians and Historians*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qt04h0308g.Pdf

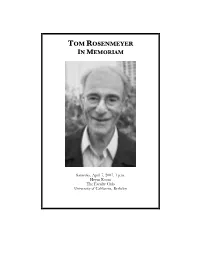

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Biography and Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer (1920-2007) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04h0308g Publication Date 2007-04-05 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TOM ROSENMEYER IN MEMORIAM Saturday, April 7, 2007, 1 p.m. Heyns Room The Faculty Club University of California, Berkeley PROGRAM MUSICAL SELECTIONS OPENING REMARKS: Tony Long REMEMBRANCES Robert Alter Erich Gruen John Prausnitz Michelle Zerba Kathy Fabunan MUSICAL INTERLUDE REMEMBRANCES Patricia Rosenmeyer Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Donald Mastronarde Mark Griffith CLOSING REMARKS: Tony Long RECEPTION THOMAS GUSTAV ROSENMEYER APRIL 3, 1920–FEBRUARY 6, 2007 Tom Rosenmeyer, Professor Emeritus of Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, died at his home in Oakland on Tuesday, February 6, 2007. He was 86. Born in Hamburg, Germany, on April 3, 1920, and educated at the humanistic Johanneum Gymnasium in that city from 1930 to 1938, Tom fled to England in 1939 to avoid Nazi per- secution. He enrolled at the London School of Oriental Studies, intending to learn Sanskrit, but in 1940 the British, expecting a German invasion, interned all “enemy” aliens. He was sent on to an internment camp in Canada, where the residents formed their own impromptu “university,” studying Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic as well as the classical languages together behind barbed wire. Among his colleagues in the camp were future classicist Martin Ostwald and Emil Fackenheim, who taught Tom Arabic and later became a prominent philosopher of the Shoah. Released from internment in 1942, Tom completed an undergraduate degree in Classics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1944 and took an MA in Classics at the University of Toronto in 1945 before proceeding to Harvard for his doctoral studies. -

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2002)

DECEMBER 2002 Photo Blitz: Student Visions ON THE COVER: B DAN FAIRCHILD’S [’03] PHOTOGRAPH OF PARRISH HALL MAILBOXES GRACES THE APRIL 2003 PAGE OF NEXT YEAR’S SWARTHMORE COLLEGE CALENDAR. IT IS ONE OF THOUSANDS OF PHOTOS SUBMITTED DURING THIS FALL’S “PHOTO BLITZ,” SPONSORED BY THE PUBLICATIONS OFFICE. FOR MORE STUDENT VISIONS OF SWARTHMORE, TURN TO PAGE 20. CONTENTS: HANG NGO ’05, ONE OF MORE THAN 360 STUDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE PHOTO BLITZ, SAID OF THIS PHOTO: “THE SHADOWS ARE [ONES] OF ME AND ... MY BEST FRIEND HERE, FRANCISCO CASTRO ’05 [LEFT].” DECEMBERDECEMBER 2002 2002 F e a t u r e s Cell Divisions 14 Swarthmore-educated scientists, ethicists, and legal scholars help Departments lead the stem-cell and cloning debate. L e t t e r s 3 Readers’ feedback By Tom Krattenmaker P r o f i l e s C o l l e c t i o n 4 Working Toward Through Student Current news a Better World 48 E y e s 2 0 Sam Ashelman ’37 hosted Bosnian A weeklong “Photo Blitz” reveals diplomats at Coolfont Resort.Resort students’ vision of Swarthmore. Alumni Digest 42 Connections and adventures By Elizabeth Redden ’05 By Jeffrey Lott ClassNotes 44 F o l l o w i n g Liberal Arts Correspondence from friends t h e W i n d 6 4 in a Conservative Jon Lyman ’77 enjoys the scenery L a n d 2 6 and sociability of ballooning. Two Swarthmoreans help start D e a t h s 5 3 a women’s college in Jeddah, Sympathy extended By Angela Doody Saudi Arabia. -

Front Matter, Table of Contents, Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Front matter, Table of Contents, Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/86t2b21j Authors Griffith, Mark Mastronarde, Donald J. Publication Date 1990-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CABINET OF THE MUSES ESSAYS ON CLASSICAL AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE IN HONOR OF THOMAS G. ROSENMEYER edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde Scholars Press Atlanta, Georgia CABINET OF THE MUSES Essays on Classical and Comparative Literature in Honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde © 1990 Scholars Press Postprint digital edition © 2005 Department of Classics, University of California, Berkeleu Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cabinet of the muses : essays on classical and comparative literature in honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer / edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde. p. cm. — (Homage series) ISBN 1-55540-408-1. -- ISBN 1-55540-409-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Classical literature-History and criticism. 2. Literature. Comparative-Classical and modern. 3. Literature. Comparative- -Modern and classical. 4. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. I. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. II. Griffith, Mark. m. Mastronarde, Donald J. IV. Series. PA26.R68C3 1989 880'.09-dc20 89-10862 CIP Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper CONTENTS Portrait of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer................................................................... -

Democratic Athens As an Experimental System: History and the Project of Political Theory

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Democratic Athens as an Experimental System: History and the Project of Political Theory. Version 1.0 November 2005 Josiah Ober Princeton University Abstract: Athens as a case study can be useful as an “exemplary narrative” for political science and normative political, on the analogy of the biologicial use of as certain animals (e.g. mice or zebrafish) as “model systems” subject to intensive study by many researchers. © Josiah Ober. [email protected] 1 What is a historical case study good for? Can the political history of classical Athens legitimately be regarded as a case study: an experimental system or exemplary narrative, useful for investigating various aspects of democracy and related phenomena? I hope to show that the answer to that question is yes, but first it seems necessary to pose an analytically prior question: What is the goal of the investigation? What precisely is the use-value of the case? What, in short, is the exemplary narrative supposed to be good for? Those questions may make a proper historian a bit queasy. She might reasonably ask: Need history be good for something other than historical knowledge itself? The point is that as soon as I say that the historical experience of (e.g.) classical Athens is an experimental system, I seem to have abandoned the historian’s tried and true ground of supposing that it is sufficient to say that Athenian history is worth studying for its own sake. I admit to a personal fondness for this sort of traditional historian’s propriety. So, as a preliminary gesture, let me plant a stake in the ground (in Greek terms: a horos) by saying that I actually do suppose that Athenian history is interesting for its own sake. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics What the Ancient Greeks Can Tell Us About Democracy. Version 1.0 September 2007 Josiah Ober Stanford The question of what the ancient Greeks can tell us about democracy can be answered by reference to three fields that have traditionally been pursued with little reference to one another: ancient history, classical political theory, and political science. These fields have been coming into more fruitful contact over the last 20 years, as evidenced by a spate of interdisciplinary work. Historians, political theorists, and political scientists interested in classical Greek democracy are increasingly capable of leveraging results across disciplinary lines. As a result, the classical Greek experience has more to tell us about the origins and definition of democracy, and about the relationship between participatory democracy and formal institutions, rhetoric, civic identity, political values, political criticism, war, economy, culture, and religion. Fortcoming in Annual Reviews in Political Science 2007 © Josiah Ober. [email protected] 1 Who are “we”? It might appear, at first glance, that there is no coherent scholarly or academic “us” who might be told something of value by studies of the ancient Greeks. The political legacy of the Greeks is very important to three major branches of scholarship -- ancient history, political theory, and political science -- and at least of collateral importance to a good many others (for example anthropology, communications, and literary studies). Ancient Greek history, political theory, and political science are distinctly different intellectual traditions, with distinctive forms of expression. Very few theorists or political scientists, for example, assume that their audiences have a reading knowledge of ancient Greek; few theorists or historians assume a knowledge of mathematics, statistics, or game theory; few historians or political scientists are comfortable with the vocabulary of normative and evaluative philosophy. -

Introduction SITING PLATO

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction SITING PLATO IN THIS BOOK I argue for a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between Plato's thought and the practice of democracy. I propose that the canonical view of Plato as a virulent antidemocrat is not sound.1 Rather, in his work, a searching consideration of the possibilities raised by some democratic ideals and institutions coexists alongside severe criticisms of democratic life and politics. Plato ®nds the lived experience and ideology of Athenian democracy repulsive and fascinating, troubling and intrigu- ing. He not only assails democratic practice but also weaves hesitations about the reach of that attack into the very presentation of his thought. A substantial measure of ambivalence, not unequivocal hostility, marks his attitude toward democracy as he knew it. This dimension of Plato's thought has remained largely unexplored for some time. This is in part because Plato has for centuries been cast as a founding ®gure in what has been called the ªantidemocratic tradition in Western thought.º2 But even when commentators have noted that state- 1 This view is longstanding and widely held, and thus I call it canonical. Typical are pas- sages such as the following: ªPlato's antipathy to democracy as he knew it thus emerges clearly in this section [the simile of the ship at Republic 487b±497a]. No doubt his anti- democratic attitude is a product of various complex factors, but what should interest us here is the philosophical ground for his condemnation of democracyº (R. -

Josiah Ober Present Position

1 JOSIAH OBER PRESENT POSITION: Constantine Mitsotakis Professsor in the School of Humanities and Sciences (Departments of Political Science and Classics). Stanford University. EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Michigan, Department of History, 1980. • Dissertation directed by Chester G. Starr: "Athenian Reactions to Military Pressure and the Defense of Attica, 404-322 B.C." B.A. University of Minnesota, Major in History, 1975 EMPLOYMENT 2006 - Stanford University. • Constantine Mitsotakis Professor in Humanities and Sciences • Professor of Political Science • Professor of Classics • Professor of Philosophy by courtesy. • Affliations: Center for the Study of Poverty and Inequality, Center for Global Justice, Urban Studies. 1990-2006. Princeton University. • 2005-2006. Affiliated faculty, Department of Politics. • 2001-2006. Professsor of Human Values. • 1993-2000. Chairman, Department of Classics. • 1993-2006. David Magie '97 Class of 1897 Professor of Classics. • 1990- 2006. Professor of Classics. 1980-1990 Montana State University. • Assistant Professor to Professor, Department of History and Philosophy. HONORS, FELLOWSHIPS, VISITING APPOINTMENTS 2009 Norwegian Acad. Arts and Sciences. Inaugural Lecture in Humanities and Social Science. 2009 President of the American Philological Association 2008 Lee Lecture in Political Science and Government. All Souls College. Oxford. 2007 Balmuth Lectures. Tufts University. 2006 University of Sydney. Visiting Fellow 2004-9 Center for Hellenic Studies (Washington DC). Senior Fellow. 2004-5 Center for the Advanced Study of the Behavioral Sciences. Fellowship (residential) 2004 Wesson Lectures in Problems of Democracy. Stanford University 2003-4 Paul H. Nitze Senior Fellow. St. Mary’s College (Maryland). 2003 Biggs Resident in Classics.Washington University in St. Louis. 2001 Nichols Visiting Professor in Humanities and the Public Sphere. -

Classics Newsletter 2010

Volume Seventeen Summer 2010 http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/classics/Newsletter nar for Culture and Religion in Antiquity at the University of Toronto. I am espe- EX CATH E DRA (SCRA). Devoted to exploring the context cially grateful to Professor Hugh Mason and interplay of religious traditions in the for his coordination of the Undergraduate A s another ancient world, both through formal paper Program Committee, and to the members academic year presentations and lively dialogue, SCRA who served under his benign leadership: draws to a close builds on strengths in the religions of the Professors Ben Akrigg, Jonathan Burgess, it is a pleasure to ancient Mediterranean across our units. and Dimitri Nakassis; graduate student review the Depart- Eric Tindale; and undergraduates Samuel ment’s achievements The main focus of the Department’s at- Allemang and Nigel Morton. over the past year. tention this year has been on strengthen- The revision of the ing our undergraduate programs. Having Our superb undergraduate Classics, Greek, graduate programs conducted a thorough review of both the and Latin programs have been nationally on which we worked long and hard in language and classical civilization pro- recognized again this year, with awards 2008-2009 has successfully passed the grams the undergraduate review commit- of three First Prizes to our students in the various levels of university governance tee recommended that the Department’s Classical Association of Canada National and will be implemented in the fall. We highest priority be to design (in 2010-11) Sight Translation Competitions (in Junior are very excited to be able to mount for and implement (in 2011-12) a new second- Greek, and Junior and Senior Latin); incoming and continuing graduate stu- year research methods course in Classical two Second Prizes (in Junior Greek and dents a broad slate of reading and research Studies that could be required for all ma- Senior Latin); and an Honorable Men- seminars, which showcase the strengths jors and specialists (i.e., not only in Clas- tion (in Senior Latin). -

Papers in Memory of Martin Ostwald Introduction

Dodds and the Irrational: Papers in Memory of Martin Ostwald Introduction The papers included in the second part of volume XXXI of Scripta Classica Israelica were delivered at a conference which took place on March 30-31, 2011, at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The conference was dedicated to the memory of the outstanding ancient historian and Classical scholar Martin Ostwald. Martin maintained excellent relations, both professional and personal, with most of the classicists and ancient historians of the Israeli Classical establishment, frequented the meetings of the Israel Society for the Promotion of Classical Studies for many years, and contributed articles to Scripta Classical Israelica. Prima facie, Martin and the subject of this conference did not fit together well. Martin Ostwald was intensely rational. He admired Thucydides, that most rational of ancient historians, and translated into English some of the writings of Aristotle, that most rational of ancient philosophers. The papers delivered at the conference dealt with subjects such as sacrifice, emotional displays, gods, madness, epiphanies, illnesses, mental states, paradoxes and magic, in conformity with the dichotomy drawn by E.R. Dodds as early as 1951. However, as all the speakers approached the irrational from a rational point of view, it is likely that Martin would not have disapproved. After all, as pointed out by his son Mordecai in the biography that follows, the subordination in Greek culture of ever more irrational aspects of human nature to the rule of reason was a central theme in his thought. Gabriel Herman Scripta Classica Israelica vol. XXXI 2012 p. 85 Martin Ostwald 15 January 1922 - 10 April 2010 15 Tevet 5682 - 26 Nisan 5770 Martin Ostwald, my father, was born in Dortmund Westphalia to Max Ostwald, a prominent lawyer, and his wife Hedwig née Strauss, on January 15, 1922. -

Nomos and Phusis in Antiphon's Peri AlêTheias

NOMOS AND PHUSIS IN ANTIPHON’S * Martin Ostwald Swarthmore College and University of Pennsylvania The central importance of Antiphon, the author of the tract On Truth, for students of philosophy and history alike, needs no argumPenetr. ‹ N ÉoAt olnhlyy ise ¤hae wthe earliest Athenian sophist intelligible to us, but he is also the most explicit exponent of the nomos-phusis controversy which emerged in Athens in the 420s and was to prove seminal in the development of Western thought; for the historian, its author presents the tantalizing problem whether he is or is not identical with the politician who, according to Thucydides (8.68.1), orchestrated the oligarchical revolution of 411 B.C. Moreover, the publication in 1984 of a new fragment by Maria Serena Funghi1 has renewed interest in both author and tract.2 This spate of recent publications, when added to the formidable array of earlier discussions by a formidable array of scholars,3 may make the addition of yet another interpretation a foolhardy enterprise. Yet it seems possible to show that a new perspective on the tract can be gained, which not only places it more closely into the context of contemporary discussions of nomos and phusis but also takes greater account of the fragmentary nature of the tract, and attempts to do greater justice to POxy. 1797 (now commonly labelled C), which is believed by some to belong to a different book of this tract. The following translation, adapted from that by Jonathan Barnes,4 is based on the new text published in the first fascicle of the Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini by F. -

Tom Rosenmeyer in Memoriam

TOM ROSENMEYER IN MEMORIAM Saturday, April 7, 2007, 1 p.m. Heyns Room The Faculty Club University of California, Berkeley PROGRAM MUSICAL SELECTIONS OPENING REMARKS: Tony Long REMEMBRANCES Robert Alter Erich Gruen John Prausnitz Michelle Zerba Kathy Fabunan MUSICAL INTERLUDE REMEMBRANCES Patricia Rosenmeyer Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Donald Mastronarde Mark Griffith CLOSING REMARKS: Tony Long RECEPTION THOMAS GUSTAV ROSENMEYER APRIL 3, 1920–FEBRUARY 6, 2007 Tom Rosenmeyer, Professor Emeritus of Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, died at his home in Oakland on Tuesday, February 6, 2007. He was 86. Born in Hamburg, Germany, on April 3, 1920, and educated at the humanistic Johanneum Gymnasium in that city from 1930 to 1938, Tom fled to England in 1939 to avoid Nazi per- secution. He enrolled at the London School of Oriental Studies, intending to learn Sanskrit, but in 1940 the British, expecting a German invasion, interned all “enemy” aliens. He was sent on to an internment camp in Canada, where the residents formed their own impromptu “university,” studying Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic as well as the classical languages together behind barbed wire. Among his colleagues in the camp were future classicist Martin Ostwald and Emil Fackenheim, who taught Tom Arabic and later became a prominent philosopher of the Shoah. Released from internment in 1942, Tom completed an undergraduate degree in Classics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1944 and took an MA in Classics at the University of Toronto in 1945 before proceeding to Harvard for his doctoral studies. He took up his first teaching job in 1947 at the University of Iowa, where he worked on completing his dissertation and began translating Bruno Snell’s Die Entdeckung des Geistes, which appeared in 1948. -

RALPH MARK ROSEN Department of Classical Studies 310 S. 36Th St

RALPH MARK ROSEN CURRICULUM VITAE Rev. 04-10-21 Department of Classical Studies 310 S. 36th St., MB #4, 202 Claudia Cohen Hall Philadelphia, PA 19104 University of Pennsylvania Tel: 610-291-8075 Philadelphia, PA 19104-6304 [email protected] Tel: 215-898-7425 Birthdate: March 7, 1956 EDUCATION Ph.D. Harvard University Classical Philology 1983 M.A. Harvard University Classical Philology 1979 B.A. Swarthmore College Greek and Latin 1977 RESEARCH AND TEACHING INTERESTS Greek and Latin literature; Ancient comedy and satire; Aristophanes; Greek philosophy and aesthetics; Ancient medicine; Galen. ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS 2014-: Vartan Gregorian Professor of the Humanities 2006-2014: Rose Family Endowed Term Professor 2000-: Professor, Department of Classical Studies: University of Pennsylvania 1993-2000: Associate Professor and Department Chair: University of Pennsylvania 1989-93: Associate Professor and Undergraduate Chair: University of Pennsylvania 1983-88: Assistant Professor and Undergraduate Chair: University of Pennsylvania HONORS AND AWARDS 2020 Loeb Classical Library Foundation Fellowship 2015 Conference ‘Master’ and Keynote speaker, University of Groningen, Netherlands 2015 Martin Ostwald Memorial Lecturer at Swarthmore College 2015 Kemp Lecturer in the Humanities, University of Missouri 2014 Vartan Gregorian Professor of the Humanities 2013 Leiden University, NL: Spinoza Visiting Professor, Fall term. 2012 Battle Lecturer at University of Texas, Austin 2012 Fellow, Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies (NIAS) Spring term Rosen CV, p. 2 2011 Bertrand Lecturer in Classics, UC San Francisco 2011 Rothman Foundation Lecturer, University of Florida 2011 Endowed Ostwald Memorial Lecturer, University of Tel Aviv 2008 Jay C. and Ruth Halls Visiting Scholar in Classics, U. Wisconsin 2008 Distinguished Visiting Scholar, St.