Introduction SITING PLATO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gregory Vlastos, Socrates

72 Gregory Vlastos, Socrates: Ironist and ~oral Philosopher (Cam bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), ISBN 0 521 307333 hardback £35/$57-50; ISB~ 0 521 31450X paperback £11-95/S16-95. Socrates: Ironist and Noral Philosopher (SINP) is a book that all students of Socrates and of Greek philosophy will have to read, and will benefit from reading. It isn't the complete portrait of Socrates that many of us hoped it would be (for example, it contains no full discussion of the elenchus) and it is not all new much of it is already familiar from journal articles. It reads, indeed, more like a collection of articles than a unified book, but it is none the less engaging and provocative for that, the product of hard thinking by a major scholar and a life-long Socratist It is also very well written. I shall focus on only a few central themes. 1. Socrates and Plato Vlastos (pp. 46-7) divides the Platonic dialogues into four classes: (1) ELENCTIC; Apology, Charmides, Crico, Euthyphro, Gorgias, Hippias Ninor, Ion, Laches, Protagoras, Republic I (2) TRANSITIONAL: Eu thydemus, Hippias l1ajor, Lysis, l1enexenus, l1eno (3) MIDDLE: Cratylus, Phaedo, Symposium, Republic II-X, Phaedrus, Parmenides, Theaetetus (4) LATE: Timaeus, Crit ias, Sophist, Politicus, Philebus, Laws 73 He believes that the protagonist of the elenctic dialogues ("SocratesE") is the historical Socrates. while the protagonist of the middle and later dialogues ("SocratesM") is little more than a mouthpiece for Plato. Many scholars would go along with this thesis. but they might well balk at the members of (2). -

Sophist Revisited Trends in Classics Q Supplementary Volumes

Plato’s Sophist Revisited Trends in Classics Q Supplementary Volumes Edited by Franco Montanari and Antonios Rengakos Scientific Committee Alberto Bernabe´ · Margarethe Billerbeck · Claude Calame Philip R. Hardie · Stephen J. Harrison · Stephen Hinds Richard Hunter · Christina Kraus · Giuseppe Mastromarco Gregory Nagy · Theodore D. Papanghelis · Giusto Picone Kurt Raaflaub · Bernhard Zimmermann Volume 19 De Gruyter Plato’s Sophist Revisited Edited by Beatriz Bossi Thomas M. Robinson De Gruyter ISBN 978-3-11-028695-3 e-ISBN 978-3-11-028713-4 ISSN 1868-4785 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Ą 2013 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Logo: Christopher Schneider, Laufen Printing: Hubert & Co. GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ϱ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Preface This book consists of a selection of papers presented at the International Spring Seminar on Plato’s Sophist (26–31 May 2009, Centro de Ciencias de Benasque ‘Pedro Pascual’, Spain) with the financial support of MI- CINN, CSIC, Universidad de Zaragoza and Gobierno de Aragón. The Conference was organized by the editors, under the auspices of the Director of the Centre, Prof. José Ignacio Latorre, who provided invaluable assistance at every stage of the Conference, up to its close with a lecture on Quantum Physics for Philosophers. The aim of the conference was the promotion of Plato studies in Spain in the framework of discussions with a number of international scholars of distinction in the field, whilst at the same time looking afresh at one of Plato’s most philosophically profound dialogues. -

Gregory Vlastos

Gregory Vlastos: A Preliminary Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Vlastos, Gregory, 1907-1991 Title: Gregory Vlastos Papers Dates: circa 1930s-1991 Extent: 100 document boxes (42.00 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of philosopher Gregory Vlastos, a scholar of ancient Greek philosophy who spent most of his career studying the thought of Plato and Socrates, document his studies, his writings, and his career as an educator at several American universities. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4361 Language: English, with Ancient Greek, French, German, Italian, Latin, Modern Greek, and Spanish Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gifts, 1993-2010 (G9070, G9134, G9163, G9225, G9252, G9628, G9979, G9982, G10214, G10288, G11877, 10-03-014-G) Processed by: Hope Rider, 2006; updated by Joan Sibley, 2016 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Vlastos, Gregory, 1907-1991 Manuscript Collection MS-4361 Scope and Contents The papers of philosopher Gregory Vlastos (1907-1991), a scholar of ancient Greek philosophy who spent most of his career studying the thought of Plato and Socrates, document his studies, his writings, and his career as an educator at several American universities, especially Cornell, Princeton, and The University of California at Berkeley. The papers are arranged in six series: I. Correspondence and Offprint Files, II. Study, Lecture, and Teaching Files, III. Works, IV. Works by Others, V. Miscellaneous, and VI. Offprints Removed from Manuscripts. The Correspondence and Offprint Files (35 boxes) in Series I. represent Vlastos' extensive correspondence with other philosophers, classicists, former students, academics, and others. The files are arranged alphabetically by correspondent name, and generally include not only letters received, but copies of Vlastos' responses. -

The Science of Philosophy: Discourse and Deception in Plato's Sophist

The Science of Philosophy - Discourse and Deception in Plato’s Sophist - For Epoché [Penultimate ver.] The Science of Philosophy: Discourse and Deception in Plato’s Sophist Olof Pettersson Abstract: At 252e1 to 253c9 in Plato’s Sophist, the Eleatic Visitor explains why philosophy is a science. Like the art of grammar, philosophical knowledge corresponds to a generic structure of discrete kinds and is acquired by systematic analysis of how these kinds intermingle. In the literature, the Visitor’s science is either understood as an expression of a mature and authentic platonic metaphysics, or as a sophisticated illusion staged to illustrate the seductive lure of sophistic deception. By showing how the Visitor’s account of the science of philosophy is just as comprehensive, phantasmatic and self-concealing as the art of sophistry identified at the dialogue’s outset, this paper argues in favor of the latter view. Introduction At 252e1 to 253c9 in Plato’s Sophist, the Eleatic Visitor1 explains what he means by philosophy. Like the art of grammar, philosophy is about parts: All things can be analyzed. But not all parts fit together. Just like the letters of the alphabet, some can be combined and some cannot. According to the Visitor, it is knowledge about this that constitutes philosophy (253d1-e2) – a science he classifies as the greatest of them all (253c4-9). In the literature there are two main takes on this. Either the Visitors’ philosophical science is taken to be an expression of an authentic and mature platonic metaphysics; or it is said to be a sophisticated illusion staged to illustrate the seductive lure of sophistic deception. -

Qt04h0308g.Pdf

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Biography and Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer (1920-2007) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04h0308g Publication Date 2007-04-05 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TOM ROSENMEYER IN MEMORIAM Saturday, April 7, 2007, 1 p.m. Heyns Room The Faculty Club University of California, Berkeley PROGRAM MUSICAL SELECTIONS OPENING REMARKS: Tony Long REMEMBRANCES Robert Alter Erich Gruen John Prausnitz Michelle Zerba Kathy Fabunan MUSICAL INTERLUDE REMEMBRANCES Patricia Rosenmeyer Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Donald Mastronarde Mark Griffith CLOSING REMARKS: Tony Long RECEPTION THOMAS GUSTAV ROSENMEYER APRIL 3, 1920–FEBRUARY 6, 2007 Tom Rosenmeyer, Professor Emeritus of Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, died at his home in Oakland on Tuesday, February 6, 2007. He was 86. Born in Hamburg, Germany, on April 3, 1920, and educated at the humanistic Johanneum Gymnasium in that city from 1930 to 1938, Tom fled to England in 1939 to avoid Nazi per- secution. He enrolled at the London School of Oriental Studies, intending to learn Sanskrit, but in 1940 the British, expecting a German invasion, interned all “enemy” aliens. He was sent on to an internment camp in Canada, where the residents formed their own impromptu “university,” studying Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic as well as the classical languages together behind barbed wire. Among his colleagues in the camp were future classicist Martin Ostwald and Emil Fackenheim, who taught Tom Arabic and later became a prominent philosopher of the Shoah. Released from internment in 1942, Tom completed an undergraduate degree in Classics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1944 and took an MA in Classics at the University of Toronto in 1945 before proceeding to Harvard for his doctoral studies. -

The Mathematical Anti-Atomism of Plato's Timaeus

The mathematical anti-atomism of Plato’s Timaeus Luc Brisson, Salomon Ofman To cite this version: Luc Brisson, Salomon Ofman. The mathematical anti-atomism of Plato’s Timaeus. Ancient Philoso- phy, Philosophy Documentation Center, In press. hal-02923266 HAL Id: hal-02923266 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02923266 Submitted on 26 Aug 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The mathematical anti-atomism of Plato’s Timaeus Luc Brisson Salomon Ofman Centre Jean Pépin CNRS-Institut mathématique de Jussieu- CNRS-UMR 8230 Paris Rive Gauche École normale supérieure Sorbonne Université Paris Sciences Lettres Paris Université Abstract. In Plato’s eponymous dialogue, Timaeus, the main character presents the universe as an almost perfect sphere filled by tiny invisible particles having the form of four regular polyhedrons. At first glance, such a construction may seem close to an atomic theory. However, one does not find any text in Antiquity tying Timaeus’ cosmology to the atomists, and Aristotle made a clear distinction between Plato and the latter. Despite the cosmology in the Timaeus is so far apart from the one of the atomists, Plato is commonly presented in contemporary literature as some sort of atomist, sometimes as supporting a so-called form of ‘mathematical atomism’. -

AN INTRODUCTION to PRE-SOCRATIC ETHICS: HERACLITUS and DEMOCRITUS on HUMAN NATURE and CONDUCT (PART I: on MOTION and CHANGE) Erman Kaplama

Cosmos and History: The Journal of Natural and Social Philosophy, vol. 17, no. 1, 2021 AN INTRODUCTION TO PRE-SOCRATIC ETHICS: HERACLITUS AND DEMOCRITUS ON HUMAN NATURE AND CONDUCT (PART I: ON MOTION AND CHANGE) Erman Kaplama ABSTRACT: Both Heraclitus and Democritus, as the philosophers of historia peri phuseôs, consider nature and human character, habit, law and soul as interrelated, emphasizing the links between phusis, kinesis, ethos, logos, kresis, nomos and daimon. On the one hand, Heraclitus’s principle of change (panta rhei) and his emphasis on the element of fire and cosmic motion ultimately dominate his ethics, reinforcing his ideas of change, moderation, balance and justice; on the other, Democritus’s atomist description of phusis and motion underlies his principle of moderation and his ideas of health and measured life. In this series, particularly referring to the main principles of motion, moderation and justice, I attempt to describe a coherent pre-Socratic ethical perspective based on the Heraclitean and Democritean fragments. I explore the connections between their physics and ethics, also borrowing from Nietzsche’s lectures and writings on the Pre-Socratics. I redefine such Heraclitean and Democritean concepts as harmony, order, perfection, health, self-control, contentment, cheerfulness, concord, sound judgment, wisdom, measure and balance and discuss them under the principles of motion (phusis), moderation (sophrosyne) and justice. In doing so, I also expose the relevance of the Heraclitean notion of logos (interpreting it as the underlying categorical principle of transition between phusis and ethos) in bringing together these ideas and principles. Finally, based on this pre-Socratic Weltanschauung, I assess the possibility of a coherent picture of humanity, its nature and conduct as extending from or fitting into or extending-from-when- fitting-into the cosmos of moving forces and atoms. -

Rethinking Bernard Williams' Criticism of the City-Soul Analogy in Plato's Republic

The 3rd BESETO Conference of Philosophy Session 14 Rethinking Bernard Williams’ Criticism of the City-Soul Analogy in Plato’s Republic (draft) WU Tianyue Peking University Abstract This essay takes a close look at Bernard Williams’ criticism of the city-soul analogy in Plato’s Republic, which “has dominated the discussion of its subject ever since.” (Myles Burnyeat). I start with reviving Williams’ arguments to elucidate the genuine challenge to Plato’s theory of justice by introducing city-soul analogy. The second part of this essay aims to show that Williams’ critics, such as Jonathan Lear, G.R.F. Ferrari, and Nobert Blössner have not successfully solved the problems Williams brought forth in his article. Finally, I call attention to a neglected aspect of the city-soul analogy, i.e. the predominance of reason in Plato’s theory of justice. By carefully analyzing Plato’s account of justice and briefly addressing the discussion about philosopher-kings in Book V–VII, I argue that Plato actually defines justice as the rule of the reasoning part. With this new definition of justice, the city-soul analogy will be shown philo- sophically accountable within the whole argumentative structure of Republic. It is well known that Republic is not an accurate translation of the ancient Greek word πολιτεία, whose meanings range from “condition and rights of a citizen” to “constitution of a state”1. The Chinese translation Li Xiang Guo, which literally means the ideal state, even goes further to iden- tify Plato’s magnum opus as a utopian writing. However, Plato’s or Socrates’ mythical narrative2 of the ideal city (καλλιπόλις) and its constitution starts rather late in the middle of Book II of Republic. -

Confusion About the Socratic Method

68 Confusion About the Socratic Method Confusion about the Socratic Method: Socratic Paradoxes and Contemporary Invocations of Socrates Rob Reich Stanford University Ask the average person, “Who was Socrates and what did he do?” and you are likely to get the following response: Socrates was a old philosopher who bothered people with questions and was ultimately put to death. Almost twenty-five hundred years after placidly drinking the hemlock, what we remember Socrates for is his habitual questioning, his demand to live an examined life.1 The figure of Socrates is in ordinary discourse synonymous with his method — the Socratic method. Contemporary scholars echo this commonplace opinion. Gregory Vlastos, who devoted his entire life to Socratic scholarship, reflects that the Socratic method is Socrates’ “greatest contribution” and moreover, one which ranks “among the greatest achievements of humanity.”2 The results of Socrates’ life, the conclusions he drew about how we ought to live, Vlastos argues, are less important than the manner in which he conducted his life, the style of inquiry he originated and bequeathed to future generations. Indeed, aside from philosophers, few today could identify what specific beliefs Socrates held. In contrast to most other great thinkers, Socrates’ primary legacy is not a contribution to humanity’s storehouse of knowl- edge, but a pedagogy; not substance but process. To overstate only slightly, for Socrates, and for our understanding of him, method is all. Yet despite the general acknowledgment of Socrates’ achievement, it is not at all clear what exactly the Socratic method is, and more specifically, what the Socratic method does, either in the dialogues or in contemporary invocations. -

The Republic and Allegory

Studia Antiqua Volume 4 Number 1 Article 3 April 2005 Plato in Context: The Republic and Allegory Joseph Spencer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Classics Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Spencer, Joseph. "Plato in Context: The Republic and Allegory." Studia Antiqua 4, no. 1 (2005). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Plato in Context: The Republic and Allegory JOSEPH SPENCER n his early work, The Birth rif Tragetfy, Friedrich Nietzsche promoted the idea that Plato was the source of everything I strait-laced in Western civilization. For Nietzsche, that meant that Plato had ruined the fun because he had repressed the Dionysian camp, casting himself prostrate before the Socratic altar. Because Nietzsche's claim was well received in his era of continental confusion and soul-searching, scholarship since has inherited the prejudiced opinion that the ancient philosopher was more than a little tainted with predilections toward the clear!J pious and saintly Apollonian Athenian.l Hundreds of volumes written in the last century are built on the premise that Plato was as we say he was-that there was not much more to him than his Theory of Forms and a few other idealist propositions. Indeed, once a conclusion has been drawn, it is easy to simply insert it again and again into the primary texts. -

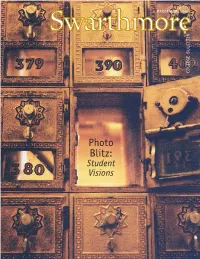

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2002)

DECEMBER 2002 Photo Blitz: Student Visions ON THE COVER: B DAN FAIRCHILD’S [’03] PHOTOGRAPH OF PARRISH HALL MAILBOXES GRACES THE APRIL 2003 PAGE OF NEXT YEAR’S SWARTHMORE COLLEGE CALENDAR. IT IS ONE OF THOUSANDS OF PHOTOS SUBMITTED DURING THIS FALL’S “PHOTO BLITZ,” SPONSORED BY THE PUBLICATIONS OFFICE. FOR MORE STUDENT VISIONS OF SWARTHMORE, TURN TO PAGE 20. CONTENTS: HANG NGO ’05, ONE OF MORE THAN 360 STUDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE PHOTO BLITZ, SAID OF THIS PHOTO: “THE SHADOWS ARE [ONES] OF ME AND ... MY BEST FRIEND HERE, FRANCISCO CASTRO ’05 [LEFT].” DECEMBERDECEMBER 2002 2002 F e a t u r e s Cell Divisions 14 Swarthmore-educated scientists, ethicists, and legal scholars help Departments lead the stem-cell and cloning debate. L e t t e r s 3 Readers’ feedback By Tom Krattenmaker P r o f i l e s C o l l e c t i o n 4 Working Toward Through Student Current news a Better World 48 E y e s 2 0 Sam Ashelman ’37 hosted Bosnian A weeklong “Photo Blitz” reveals diplomats at Coolfont Resort.Resort students’ vision of Swarthmore. Alumni Digest 42 Connections and adventures By Elizabeth Redden ’05 By Jeffrey Lott ClassNotes 44 F o l l o w i n g Liberal Arts Correspondence from friends t h e W i n d 6 4 in a Conservative Jon Lyman ’77 enjoys the scenery L a n d 2 6 and sociability of ballooning. Two Swarthmoreans help start D e a t h s 5 3 a women’s college in Jeddah, Sympathy extended By Angela Doody Saudi Arabia. -

![Necessity and Form-Copies: Republic, Timaeus, and Laws [Abstract] Plato's Metaphysics Employs Three Distinct Ontological State](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0285/necessity-and-form-copies-republic-timaeus-and-laws-abstract-platos-metaphysics-employs-three-distinct-ontological-state-2310285.webp)

Necessity and Form-Copies: Republic, Timaeus, and Laws [Abstract] Plato's Metaphysics Employs Three Distinct Ontological State

Necessity and Form-Copies: Republic, Timaeus, and Laws [Abstract] Plato’s metaphysics employs three distinct ontological states: Forms, particulars, and form-copies. Fundamentally, Forms are static beings; particulars are dynamic non-beings; form- copies are dynamic instances of being(s). Plato’s metaphysics is met with difficulty when we start to question how exactly form-copies, mixtures of two seemingly incompatible ontological states (Forms and particulars), come into existence. In this paper, I offer an analysis concerning the relationship between Plato’s two cosmological causes (i.e. Reason and Necessity) and form- copy generation. I am chiefly interested in what finalizes the union between particulars and Forms to generate form-copies. I refer to this finalizing agent as the “form-copy agent.” Plato puts forth two causes: Reason and Necessity. Both Reason and Necessity possess operative limits (authority) defined by causal capabilities. The abstract parts and machinery are subsumed under Reason, while Necessity is broadly associated with physical reality. The causal role of Reason is to define all being. Necessity’s causal role, on the other hand, remains somewhat obscure. If Reason defines being, what does Necessity accomplish as a cause? Plato’s metaphysics needs a catalyzing agent that can account for particulars’ transition into form- copies. Necessity, I argue, is this agent. 1 Introduction In Plato’s first real attempts to outline the theory of Forms (Phaedo), two principal modes of being are posited: being (οὐσία) and participation (μετέχειν). These two modes of being give rise to three definitive ontological states: Forms, particulars, and form-copies. Forms are defined by being (οὐσία).