Democratic Athens As an Experimental System: History and the Project of Political Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

Michels's Iron Law of Oligarchy

MICHELS’S IRON LAW OF OLIGARCHY Robert Michels ( 1876– 1936), was a young historian who had been unable to get a job in the German university system, despite the recommendation of Max Weber, because he was a member of the Social Democrats. Michels had participated extensively in party activities and had come to the conclusion that the Socialists did not live up to their own ideals. Although the party advocated democracy, it was not internally democratic itself. The revolutionary Marxism of the speeches at conventions and on the floor of the Reichstag was just a way of whipping up support among the workers, while the party leaders built a bureaucratic trade union and party machine to provide sinecures for themselves. Michels’s analysis appeared in 1911 in a book called Political Parties. The phenomenon of party oligarchy was quite general, stated Michels; if internal democracy could not be found in an organization that was avowedly democratic, it would certainly not exist in parties which did not claim to be democratic. This principle was called the Iron Law of Oligarchy, and it constitutes one of the great generalizations about the functioning of mass‐ membership organizations, as subsequent research has borne out. The Iron Law of Oligarchy works as follows: First of all, there is always a rather small number of persons in the organization who actually make decisions, even if the authority is formally vested in the body of the membership at large. The reason for this is purely functional and will be obvious to anyone who has attended a public meeting or even a large committee session. -

Qt04h0308g.Pdf

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Biography and Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer (1920-2007) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04h0308g Publication Date 2007-04-05 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TOM ROSENMEYER IN MEMORIAM Saturday, April 7, 2007, 1 p.m. Heyns Room The Faculty Club University of California, Berkeley PROGRAM MUSICAL SELECTIONS OPENING REMARKS: Tony Long REMEMBRANCES Robert Alter Erich Gruen John Prausnitz Michelle Zerba Kathy Fabunan MUSICAL INTERLUDE REMEMBRANCES Patricia Rosenmeyer Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Donald Mastronarde Mark Griffith CLOSING REMARKS: Tony Long RECEPTION THOMAS GUSTAV ROSENMEYER APRIL 3, 1920–FEBRUARY 6, 2007 Tom Rosenmeyer, Professor Emeritus of Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, died at his home in Oakland on Tuesday, February 6, 2007. He was 86. Born in Hamburg, Germany, on April 3, 1920, and educated at the humanistic Johanneum Gymnasium in that city from 1930 to 1938, Tom fled to England in 1939 to avoid Nazi per- secution. He enrolled at the London School of Oriental Studies, intending to learn Sanskrit, but in 1940 the British, expecting a German invasion, interned all “enemy” aliens. He was sent on to an internment camp in Canada, where the residents formed their own impromptu “university,” studying Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic as well as the classical languages together behind barbed wire. Among his colleagues in the camp were future classicist Martin Ostwald and Emil Fackenheim, who taught Tom Arabic and later became a prominent philosopher of the Shoah. Released from internment in 1942, Tom completed an undergraduate degree in Classics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1944 and took an MA in Classics at the University of Toronto in 1945 before proceeding to Harvard for his doctoral studies. -

The Iron Law of Oligarchy: a Tale of 14 Islands ∗

The Iron Law of Oligarchy: A Tale of 14 Islands ∗ Christian Dippely Jean Paul Carvalhoz December 15, 2014 Abstract The great puzzle of Caribbean history in the mid-19th century is that this was a time of radical institutional change – with all but one of the long-established Caribbean parliaments voting themselves out of existence inside a twenty-year window – despite very stable conditions in the (exogenous) terms-of-trade and in the (endogenous) local plantation economy. This paper argues that the post-slavery change of the planter elite into a more creole and colored composition did not change the incentives of the coercive Caribbean plantation economy, but that it did undermine the elite’s ability to dominate the political process within the given set of formal institutions, i.e. the locally elected parliaments. The new elite needed a new set of formal institutions to maintain the existing coercive institutional bundle. The first argument is a version of the ”iron law of oligarchy” (Michels (1911)), the second a version of the ”seesaw of de jure and de facto institutions” (Acemoglu and Robinson (2008)). Guided by a model of elite coherence and institutional choice, we explore our two arguments in a combination of very rich micro-data on islands’ parliamentary politics and sugar plantations, as well as colony-level regression analysis. Keywords: Iron law of Oligarchy, Bankruptcy, de jure and de facto Institutions, Economic Development JEL Codes: F54, N26, O43, P16 ∗Financial support from UCLA’s Burkle Center, Center for Economic History and Price Center are gratefully acknowledged. yUniversity of California, Los Angeles, and NBER. -

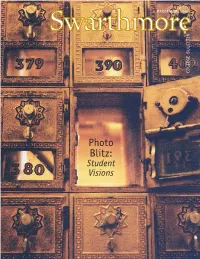

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2002)

DECEMBER 2002 Photo Blitz: Student Visions ON THE COVER: B DAN FAIRCHILD’S [’03] PHOTOGRAPH OF PARRISH HALL MAILBOXES GRACES THE APRIL 2003 PAGE OF NEXT YEAR’S SWARTHMORE COLLEGE CALENDAR. IT IS ONE OF THOUSANDS OF PHOTOS SUBMITTED DURING THIS FALL’S “PHOTO BLITZ,” SPONSORED BY THE PUBLICATIONS OFFICE. FOR MORE STUDENT VISIONS OF SWARTHMORE, TURN TO PAGE 20. CONTENTS: HANG NGO ’05, ONE OF MORE THAN 360 STUDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE PHOTO BLITZ, SAID OF THIS PHOTO: “THE SHADOWS ARE [ONES] OF ME AND ... MY BEST FRIEND HERE, FRANCISCO CASTRO ’05 [LEFT].” DECEMBERDECEMBER 2002 2002 F e a t u r e s Cell Divisions 14 Swarthmore-educated scientists, ethicists, and legal scholars help Departments lead the stem-cell and cloning debate. L e t t e r s 3 Readers’ feedback By Tom Krattenmaker P r o f i l e s C o l l e c t i o n 4 Working Toward Through Student Current news a Better World 48 E y e s 2 0 Sam Ashelman ’37 hosted Bosnian A weeklong “Photo Blitz” reveals diplomats at Coolfont Resort.Resort students’ vision of Swarthmore. Alumni Digest 42 Connections and adventures By Elizabeth Redden ’05 By Jeffrey Lott ClassNotes 44 F o l l o w i n g Liberal Arts Correspondence from friends t h e W i n d 6 4 in a Conservative Jon Lyman ’77 enjoys the scenery L a n d 2 6 and sociability of ballooning. Two Swarthmoreans help start D e a t h s 5 3 a women’s college in Jeddah, Sympathy extended By Angela Doody Saudi Arabia. -

How Political Parties Shape Democracy

UC Irvine CSD Working Papers Title HOW POLITICAL PARTIES SHAPE DEMOCRACY Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/17p1m0dx Author van Biezen, Ingrid Publication Date 2004-11-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu This paper assesses the relationship between the nature of political parties and varieties of democracy1. It is argued that the changing role of parties can be attributed to an ideational transformation by which parties have gradually come to be seen as necessary and desirable institutions for democracy, and that this has contributed to a changing conception of parties from voluntary private associations towards the political party as a ‘public utility’, i.e. the party as an essential public good for democracy. Recent cases of democratization, where parties were attributed a markedly privileged position within the democratic institutional framework, provide the most unequivocal testimony of such a conception of the relationship between parties and democracy. At the same time, however, fundamental disagreements persist about the meaning of democracy and the actual role of political parties within it. Regrettably, however, the literatures on parties and democratic theory have developed to a large degree in mutual isolation. This paper provides a preliminary attempt to move beyond the consensus which exists on the surface that modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of parties by considering varieties of party and different conceptions of democracy. On the Paradox of Party As Schattschneider famously asserted more than half a century ago, ‘the political parties created democracy and modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the political parties’ (Schattschneider, 1942:1). -

Front Matter, Table of Contents, Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Front matter, Table of Contents, Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/86t2b21j Authors Griffith, Mark Mastronarde, Donald J. Publication Date 1990-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CABINET OF THE MUSES ESSAYS ON CLASSICAL AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE IN HONOR OF THOMAS G. ROSENMEYER edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde Scholars Press Atlanta, Georgia CABINET OF THE MUSES Essays on Classical and Comparative Literature in Honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde © 1990 Scholars Press Postprint digital edition © 2005 Department of Classics, University of California, Berkeleu Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cabinet of the muses : essays on classical and comparative literature in honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer / edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde. p. cm. — (Homage series) ISBN 1-55540-408-1. -- ISBN 1-55540-409-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Classical literature-History and criticism. 2. Literature. Comparative-Classical and modern. 3. Literature. Comparative- -Modern and classical. 4. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. I. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. II. Griffith, Mark. m. Mastronarde, Donald J. IV. Series. PA26.R68C3 1989 880'.09-dc20 89-10862 CIP Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper CONTENTS Portrait of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer................................................................... -

Extra-Party Neo-Anarchist Critiques AQ: Please

Rapp, John A. "Extra-Party neo-anarchist critiques AQ: Please clarify whether you want this word to read critiques as in the running head and also that the same change can be carried out in the FM also. of the state in the PRC." Daoism and Anarchism: Critiques of State Autonomy in Ancient and Modern China. London: Continuum, 2012. 175–192. Contemporary Anarchist Studies. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 29 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501306778.ch-008>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 29 September 2021, 03:37 UTC. Copyright © John A. Rapp 2012. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 8 Extra-Party neo-anarchist critiques of the state in the PRC Introduction This chapter and the succeeding one examine various “neo-anarchist” critiques of the Leninist state in the PRC, from the early years of the Cultural Revolution to the beginning of the Tiananmen protests. The label of neo-anarchist in this book refers not to self-proclaimed “post-modern” anarchist critiques but to anyone in China who criticizes the Leninist state using the simple, basic, but powerful view shared by all kinds of anarchists (contradictory as they might be on their own positive agendas), namely, that the state rules for itself when it can, not for classes, interest groups, a mass of individuals, or the whole community. The term “neo-anarchist” is adapted from analysts who apply the label “neo-Marxism” to those thinkers who fi nd the Marxist class paradigm useful without necessarily being Communists. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics What the Ancient Greeks Can Tell Us About Democracy. Version 1.0 September 2007 Josiah Ober Stanford The question of what the ancient Greeks can tell us about democracy can be answered by reference to three fields that have traditionally been pursued with little reference to one another: ancient history, classical political theory, and political science. These fields have been coming into more fruitful contact over the last 20 years, as evidenced by a spate of interdisciplinary work. Historians, political theorists, and political scientists interested in classical Greek democracy are increasingly capable of leveraging results across disciplinary lines. As a result, the classical Greek experience has more to tell us about the origins and definition of democracy, and about the relationship between participatory democracy and formal institutions, rhetoric, civic identity, political values, political criticism, war, economy, culture, and religion. Fortcoming in Annual Reviews in Political Science 2007 © Josiah Ober. [email protected] 1 Who are “we”? It might appear, at first glance, that there is no coherent scholarly or academic “us” who might be told something of value by studies of the ancient Greeks. The political legacy of the Greeks is very important to three major branches of scholarship -- ancient history, political theory, and political science -- and at least of collateral importance to a good many others (for example anthropology, communications, and literary studies). Ancient Greek history, political theory, and political science are distinctly different intellectual traditions, with distinctive forms of expression. Very few theorists or political scientists, for example, assume that their audiences have a reading knowledge of ancient Greek; few theorists or historians assume a knowledge of mathematics, statistics, or game theory; few historians or political scientists are comfortable with the vocabulary of normative and evaluative philosophy. -

Democracy Embattled Francis Fukuyama Ivan Krastev Yascha Mounk Marc F

Thirtieth Anniversary Issue January 2020, Volume 31, Number 1 $15.00 Democracy Embattled Francis Fukuyama Ivan Krastev Yascha Mounk Marc F. Plattner Larry Diamond Alina Mungiu-Pippidi Michele Dunne Carl Gershman Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way Lilia Shevtsova Ladan Boroumand Christopher Walker, Shanthi Kalathil, and Jessica Ludwig Thomas Carothers Minxin Pei Ghia Nodia Andrew J. Nathan Sumit Ganguly Laura Rosenberger on This Is Not Propaganda DEMOCRACY’S INEVITABLE ELITES Ghia Nodia Ghia Nodia is director of the International School for Political Science and professor of political science at Ilia State University in Tbilisi. He is also chairman of the Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development. For five months in 2016–17, he was a Reagan-Fas- cell Democracy Fellow at the National Endowment for Democracy in Washington, D.C. Commentators who analyze and criticize populism—two activities that frequently go hand-in-hand—tend to presume that there is no such thing as populist theory. One can have a theory about populism, these ana- lysts generally believe, but populism itself is not based on a rationally defensible vision. Populism is not a concept or an ideology, but rather an attitude, a predisposition, a discursive technique, a specific kind of resentment that demagogues exploit. A theoretical foundation for populism can be found, however, in Robert Michels’s classic work of political sociology, Political Par- ties: A Sociological Study of the Oligarchical Tendencies of Modern Democracy (1911).1 It is a text worth revisiting when democracy is— or at least is perceived to be—caught up in a crisis resulting from a backlash against the alleged elite appropriation of people’s power. -

Deplorable Or Criminal”, Were in Fact So Recent. What Brings Us to Our Point

defining the ideology of extremism deplorable or criminal”, were in fact so recent. What brings us to our point is the fact that “in spite of it, they replenished the century; one against the other, sustaining each other, they fabricated their material. Simultaneous- ly very powerful, very ephemeral and very ominous, how could they mo- bilise so much hope, or so much passion in so many individuals?” (Ibid.). Furet’s analysis brought forward an interpretation that in quite clear terms reveals the mechanisms of interdependence between fascism and bolshe- vism. Being adversaries, both ideologies and for some time also political systems needed each other. Still more, they were in a relation of complic- ity regarding their common enemy: “The heftiest secret of complicity be- tween bolshevism and fascism remains however the existence of their com- mon adversary, which the both hostile doctrines reduced or exorcised with an idea that it had been in agony, and which therefore constituted their soil: very simply, democracy” (Ibid.: p. 39). Maybe it is not so important that this interpretation, which in its minute scrutiny of both historical oc- currences maintains a constant awareness of their irreducible differences, makes possible to comprehend the turning points of history such as Hitler’s and Stalin‘s temporary alliance. From a theoretical point of view, it is more instructive that Furet’s interpretation in its retrospective insight demon- strates what could be called the vulnerability of democracy. Since the rep- resentative democracy as the formal political system does not offer much else, but the rule of the abstract Law, it maintains openness for a variety of different political alternatives and unfortunately for the anti-democrat- ic ones too. -

Introduction SITING PLATO

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction SITING PLATO IN THIS BOOK I argue for a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between Plato's thought and the practice of democracy. I propose that the canonical view of Plato as a virulent antidemocrat is not sound.1 Rather, in his work, a searching consideration of the possibilities raised by some democratic ideals and institutions coexists alongside severe criticisms of democratic life and politics. Plato ®nds the lived experience and ideology of Athenian democracy repulsive and fascinating, troubling and intrigu- ing. He not only assails democratic practice but also weaves hesitations about the reach of that attack into the very presentation of his thought. A substantial measure of ambivalence, not unequivocal hostility, marks his attitude toward democracy as he knew it. This dimension of Plato's thought has remained largely unexplored for some time. This is in part because Plato has for centuries been cast as a founding ®gure in what has been called the ªantidemocratic tradition in Western thought.º2 But even when commentators have noted that state- 1 This view is longstanding and widely held, and thus I call it canonical. Typical are pas- sages such as the following: ªPlato's antipathy to democracy as he knew it thus emerges clearly in this section [the simile of the ship at Republic 487b±497a]. No doubt his anti- democratic attitude is a product of various complex factors, but what should interest us here is the philosophical ground for his condemnation of democracyº (R.