Papers in Memory of Martin Ostwald Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREEKS BETWEEN EAST and WEST GREEKS BETWEEN EAST and WEST Essays in Greek Literature and History

PUBLICATIONS OF THE ISRAEL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES SECTION OF HUMANITIES GREEKS BETWEEN EAST AND WEST GREEKS BETWEEN EAST AND WEST Essays in Greek Literature and History in Memory of David Asheri edited by Gabriel Herman and Israel Shatzman Jerusalem 2007 The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities ISBN 965-208-170-1 © The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2007 Typesetting: Judith Sternberg Printed in Israel Contents Gabriel Herman and Preface 7 Israel Shatzman Alexander Uchitel The Earliest Tyrants: From Luwian Tarwanis to Greek TÚranno$ 13 Margalit Finkelberg Mopsos and the Philistines: Mycenaean Migrants in the Eastern Mediterranean 31 Rachel Zelnick-Abramovitz Lies Resembling Truth: On the Beginnings of Greek Historiography 45 Deborah Levine Gera Viragos, Eunuchs, Dogheads, and Parrots in Ctesias 75 Daniela Dueck When the Muses Meet: Poetic Quotations in Greek Historiography 93 Ephraim David Myth and Historiography: Lykourgos 115 Gabriel Herman Rituals of Evasion in Ancient Greece 136 Gocha R. Tsetskhladze Greeks and Locals in the Southern Black Sea Littoral: A Re-examination 160 The Writings of David Asheri: A Bibliographical Listing 197 PREFACE According to a well-known Greek proverb, the office reveals the character of the statesman (Arche deixei andra). One could argue by the same token that the bibliography reveals the character of the intellectual. There are few people to whom this would apply more aptly than the man commemorated in this volume. David Asheri (1925–2000) was a dedicated scholar who lived for his work, and his personality was immersed in his writings. This brief preface will therefore focus on his literary output, eschewing as much as possible reference to his private or public life – to which he would anyhow have objected. -

On Values, Culture and the Classics — and What They Have in Common

REVIEW ARTICLES On Values, Culture and the Classics — and What They Have in Common Gabriel Herman Ralph Μ. Rosen and Ineke Sluiter (eds.), Valuing Others in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne Supplements 323. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2010. Pp. xii + 476. ISBN 9789004189218. $224.00. 1 The editors of this collection of articles, the fifth in the series “Penn-Leiden Colloquia on Ancient Values”, have embarked on an enterprise whose troublesomeness might not have been evident right at the beginning. They set out to re-frame, and then re-examine, the ancient Greek and Roman evaluative concepts and terminology pertaining to trust, fairness, and social cohesion (or, as they put it, ‘the idea that people “belong together”, as a family, a group, a polis, a community, or just as fellow human beings’, 5), in light of the rapidly evolving fields of the social and life sciences. The opening paragraph of the introduction, which elaborates Ralph Rosen’s and Ineke Sluiter’s aim, appears to be a bold and welcome departure from the formulation of aims in a long gallery of published books on ancient morality and values. I quote it in full, warning that it may appear abstruse to scholars whose routine reading does not exceed the bounds of classics: The scale of human societies has expanded dramatically since the origin of our species. From small kin-based communities of hunter-gatherers human beings have become used to large-scale societies that require trust, fairness, and cooperative behaviour even among strangers. Recent research has suggested that such norms are not just a relic from our stone-age psychological make-up, when we only had to deal with our kin-group and prosocial behaviour would thus have had obvious genetic benefits, but that over time new social norms and informal institutions were developed that enabled successful interactions in larger (even global) settings. -

REVIEW ARTICLES Periclean Athens

REVIEW ARTICLES Periclean Athens Gabriel Herman Lorel J. Samons II (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Pericles . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. xx + 343 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-00389-6 (paperback); 978-0-521-80793-7 (hardback). This companion to the age of Pericles, dated roughly 450-428 B.C., brings together eleven articles by a distinguished gallery of specialists, its declared aim being ‘to provoke as much as to inform, to stimulate the reader to further inquiry rather than to put matters to rest’ (xvii). Even though these specialists do not always see eye to eye in their judgments, their discord does not normally surface in the essays, and the end result is a coherent overview of Athenian society which succeeds in illuminating an important chapter of Greek history. This evaluation does not however apply to the book’s ‘Introduction’ and especially not to its ‘Conclusion’ (‘Pericles and Athens’), written by the editor himself. Here Samons, rather than weaving the individual contributions into a general conclusion, restates assessments of Athenian democracy that he has published elsewhere (see 23 n. 73). These are often at odds with most previous evaluations of Periclean Athens and read more like exhortations to praiseworthy behavior than historical analyses. In this review article I will comment briefly on the eleven chapters and then return to Samons’ views, my more general theme being the issue of historical judgment. Reminding us that democracy and empire often appear as irreconcilable opposites to the modern mind, Peter Rhodes in his dense, but remarkably lucid Chapter 1 (‘Democracy and Empire’) addresses the question of the relationship between Athens’ democracy and fifth-century empire. -

Qt04h0308g.Pdf

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Biography and Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer (1920-2007) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04h0308g Publication Date 2007-04-05 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TOM ROSENMEYER IN MEMORIAM Saturday, April 7, 2007, 1 p.m. Heyns Room The Faculty Club University of California, Berkeley PROGRAM MUSICAL SELECTIONS OPENING REMARKS: Tony Long REMEMBRANCES Robert Alter Erich Gruen John Prausnitz Michelle Zerba Kathy Fabunan MUSICAL INTERLUDE REMEMBRANCES Patricia Rosenmeyer Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Donald Mastronarde Mark Griffith CLOSING REMARKS: Tony Long RECEPTION THOMAS GUSTAV ROSENMEYER APRIL 3, 1920–FEBRUARY 6, 2007 Tom Rosenmeyer, Professor Emeritus of Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, died at his home in Oakland on Tuesday, February 6, 2007. He was 86. Born in Hamburg, Germany, on April 3, 1920, and educated at the humanistic Johanneum Gymnasium in that city from 1930 to 1938, Tom fled to England in 1939 to avoid Nazi per- secution. He enrolled at the London School of Oriental Studies, intending to learn Sanskrit, but in 1940 the British, expecting a German invasion, interned all “enemy” aliens. He was sent on to an internment camp in Canada, where the residents formed their own impromptu “university,” studying Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic as well as the classical languages together behind barbed wire. Among his colleagues in the camp were future classicist Martin Ostwald and Emil Fackenheim, who taught Tom Arabic and later became a prominent philosopher of the Shoah. Released from internment in 1942, Tom completed an undergraduate degree in Classics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1944 and took an MA in Classics at the University of Toronto in 1945 before proceeding to Harvard for his doctoral studies. -

104 BOOK REVIEWS Volume Is Significant As It Puts the Act of Reading Herodotus in the Spotlight

104 BOOK REVIEWS volume is significant as it puts the act of reading Herodotus in the spotlight. Eran Almagor The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Polly Low, Interstate Relations in Classical Greece . Morality and Power , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. 313 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-87206-5. This book, which owes its origin to a Cambridge Ph.D. thesis, employs theoretical approaches from the field of International Relations (hereafter IR) to challenge the widely held view that Greek interstate relations and diplomatic practices were excessively unrestrained, anarchic and violent, and that the contemporary theories of interstate behavior were correspondingly under- developed and unsophisticated. Polly Low (hereafter L.) contends that, quite to the contrary, during the period under examination (roughly 479-322 B.C.), a developed normative framework did exist, which shaped the conduct and representation of interstate relations and was underpinned by complex thinking. She concedes, however, that this thinking did not amount to the sort of highly developed IR theories that exist in modern times. L. starts her presentation with a survey of the dilemmas and debates that accompanied the formation of IR as an academic discipline in modern times. In the wake of World War I, the so- called “idealists” believed that a liberal state of mind could supersede pure military power in the conduct of interstate relations and serve as a basis for a stable world order. The conspicuous failure of the brainchild of this conception, the League of Nations, seemed however to vindicate the claim of their rival “realists”, who held that moral considerations were and should be irrelevant to the study of relations between states, as these are, and were, dominated by nothing but naked force. -

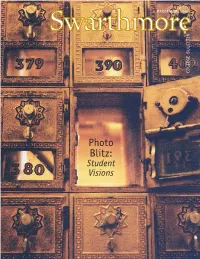

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2002)

DECEMBER 2002 Photo Blitz: Student Visions ON THE COVER: B DAN FAIRCHILD’S [’03] PHOTOGRAPH OF PARRISH HALL MAILBOXES GRACES THE APRIL 2003 PAGE OF NEXT YEAR’S SWARTHMORE COLLEGE CALENDAR. IT IS ONE OF THOUSANDS OF PHOTOS SUBMITTED DURING THIS FALL’S “PHOTO BLITZ,” SPONSORED BY THE PUBLICATIONS OFFICE. FOR MORE STUDENT VISIONS OF SWARTHMORE, TURN TO PAGE 20. CONTENTS: HANG NGO ’05, ONE OF MORE THAN 360 STUDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE PHOTO BLITZ, SAID OF THIS PHOTO: “THE SHADOWS ARE [ONES] OF ME AND ... MY BEST FRIEND HERE, FRANCISCO CASTRO ’05 [LEFT].” DECEMBERDECEMBER 2002 2002 F e a t u r e s Cell Divisions 14 Swarthmore-educated scientists, ethicists, and legal scholars help Departments lead the stem-cell and cloning debate. L e t t e r s 3 Readers’ feedback By Tom Krattenmaker P r o f i l e s C o l l e c t i o n 4 Working Toward Through Student Current news a Better World 48 E y e s 2 0 Sam Ashelman ’37 hosted Bosnian A weeklong “Photo Blitz” reveals diplomats at Coolfont Resort.Resort students’ vision of Swarthmore. Alumni Digest 42 Connections and adventures By Elizabeth Redden ’05 By Jeffrey Lott ClassNotes 44 F o l l o w i n g Liberal Arts Correspondence from friends t h e W i n d 6 4 in a Conservative Jon Lyman ’77 enjoys the scenery L a n d 2 6 and sociability of ballooning. Two Swarthmoreans help start D e a t h s 5 3 a women’s college in Jeddah, Sympathy extended By Angela Doody Saudi Arabia. -

Politics, Competition, and the Courts in Democratic Athens Susan Lape*

The State of Blame: Politics, Competition, and the Courts in Democratic Athens Susan Lape* Abstract Politics in democratic Athens routinely spilled over into the courts. From an Athenian perspective, this process was fundamentally democratic; it allowed the courts to provide a check on the power of individual political leaders and contributed to the view that the courts were the most democratic branch of Athenian government. That said, there were some downsides to transferring the scene of politics to the courts. When political issues and rivalries were brought into the courts, there was a tendency to render them into the court’s adversarial rhetoric. This translation of political issues into the polarizing language of judicial rhetoric in turn impoverished political reasoning and the political process. This study examines this broad process by first reviewing the culture of competitive honor that informed Athenian political and judicial practice, and then by examining how it operates in one famous and exceptionally competitive political trial in which politics and policy-making are center stage: Demosthenes’s prosecution of Aeschines for misconduct on the embassies leading to the Peace of Philocrates between Athens and Philip II of Macedon. The arguments and emotion strategies in this case indicate that intra-Athenian competition, both in and out of the courts, inflected the way foreign policy issues were conceptualized and understood, and was a factor in Athens’s inability to formulate a coherent policy and response to Philip of Macedon in the context of the Peace of Philocrates. * * * In the United States, the judicial system is supposed to be inoculated from political con- cerns, even though this is often more an ideal than reality. -

Front Matter, Table of Contents, Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Front matter, Table of Contents, Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/86t2b21j Authors Griffith, Mark Mastronarde, Donald J. Publication Date 1990-04-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California CABINET OF THE MUSES ESSAYS ON CLASSICAL AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE IN HONOR OF THOMAS G. ROSENMEYER edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde Scholars Press Atlanta, Georgia CABINET OF THE MUSES Essays on Classical and Comparative Literature in Honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde © 1990 Scholars Press Postprint digital edition © 2005 Department of Classics, University of California, Berkeleu Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cabinet of the muses : essays on classical and comparative literature in honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer / edited by Mark Griffith and Donald J. Mastronarde. p. cm. — (Homage series) ISBN 1-55540-408-1. -- ISBN 1-55540-409-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Classical literature-History and criticism. 2. Literature. Comparative-Classical and modern. 3. Literature. Comparative- -Modern and classical. 4. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. I. Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. II. Griffith, Mark. m. Mastronarde, Donald J. IV. Series. PA26.R68C3 1989 880'.09-dc20 89-10862 CIP Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper CONTENTS Portrait of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer................................................................... -

Democratic Athens As an Experimental System: History and the Project of Political Theory

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Democratic Athens as an Experimental System: History and the Project of Political Theory. Version 1.0 November 2005 Josiah Ober Princeton University Abstract: Athens as a case study can be useful as an “exemplary narrative” for political science and normative political, on the analogy of the biologicial use of as certain animals (e.g. mice or zebrafish) as “model systems” subject to intensive study by many researchers. © Josiah Ober. [email protected] 1 What is a historical case study good for? Can the political history of classical Athens legitimately be regarded as a case study: an experimental system or exemplary narrative, useful for investigating various aspects of democracy and related phenomena? I hope to show that the answer to that question is yes, but first it seems necessary to pose an analytically prior question: What is the goal of the investigation? What precisely is the use-value of the case? What, in short, is the exemplary narrative supposed to be good for? Those questions may make a proper historian a bit queasy. She might reasonably ask: Need history be good for something other than historical knowledge itself? The point is that as soon as I say that the historical experience of (e.g.) classical Athens is an experimental system, I seem to have abandoned the historian’s tried and true ground of supposing that it is sufficient to say that Athenian history is worth studying for its own sake. I admit to a personal fondness for this sort of traditional historian’s propriety. So, as a preliminary gesture, let me plant a stake in the ground (in Greek terms: a horos) by saying that I actually do suppose that Athenian history is interesting for its own sake. -

Greek History, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998

Sue Alcock, Graecia capta: the landscapes of Roman Greece, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. Sara B. Aleshire, The Athenian Asclepieion: the people, their dedications, and the inventories, Amsterdam: J. C. Gieben, 1989. H. Berve, Die Tyrannis bei den Griechen, München: Beck, 1967. Sue Blundell, Women in ancient Greece, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995. A. B. Bosworth, The legacy of Alexander: politics, warfare, and propaganda under the successors, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. Alain Bresson, La cité marchande, Bordeaux: Ausonius, 2000. Pierre Briant, Histoire de l’empire perse: de Cyrus à Alexandre, Paris: Fayard, 1996. Maria Brosius, Women in ancient Persia, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. Robert J. Buck, Boiotia and the Boiotian League, 432-371 B.C., Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1994. John Buckler, The Theban hegemony, 371-362 BC, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980. John Buckler, Philip II and the Sacred War, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1989. A. Bulloch, E. Gruen, A. A. Long, and A. Stewart (eds.), Images and ideologies: self- definition in the Hellenistic world, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993. Nicholas Cahill, Household and city organization at Olynthus, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. Paul Cartledge, Agesilaos and the crisis of Sparta, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987. Paul Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia: a regional history, 1300-362 BC, 2nd ed., New York and London: Routledge, 2002. David Cohen, Law, violence, and community in classical Athens, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995. Susan Guettel Cole, Landscapes, gender, and ritual space: the ancient Greek experience, Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. -

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics What the Ancient Greeks Can Tell Us About Democracy. Version 1.0 September 2007 Josiah Ober Stanford The question of what the ancient Greeks can tell us about democracy can be answered by reference to three fields that have traditionally been pursued with little reference to one another: ancient history, classical political theory, and political science. These fields have been coming into more fruitful contact over the last 20 years, as evidenced by a spate of interdisciplinary work. Historians, political theorists, and political scientists interested in classical Greek democracy are increasingly capable of leveraging results across disciplinary lines. As a result, the classical Greek experience has more to tell us about the origins and definition of democracy, and about the relationship between participatory democracy and formal institutions, rhetoric, civic identity, political values, political criticism, war, economy, culture, and religion. Fortcoming in Annual Reviews in Political Science 2007 © Josiah Ober. [email protected] 1 Who are “we”? It might appear, at first glance, that there is no coherent scholarly or academic “us” who might be told something of value by studies of the ancient Greeks. The political legacy of the Greeks is very important to three major branches of scholarship -- ancient history, political theory, and political science -- and at least of collateral importance to a good many others (for example anthropology, communications, and literary studies). Ancient Greek history, political theory, and political science are distinctly different intellectual traditions, with distinctive forms of expression. Very few theorists or political scientists, for example, assume that their audiences have a reading knowledge of ancient Greek; few theorists or historians assume a knowledge of mathematics, statistics, or game theory; few historians or political scientists are comfortable with the vocabulary of normative and evaluative philosophy. -

Introduction SITING PLATO

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction SITING PLATO IN THIS BOOK I argue for a fundamental rethinking of the relationship between Plato's thought and the practice of democracy. I propose that the canonical view of Plato as a virulent antidemocrat is not sound.1 Rather, in his work, a searching consideration of the possibilities raised by some democratic ideals and institutions coexists alongside severe criticisms of democratic life and politics. Plato ®nds the lived experience and ideology of Athenian democracy repulsive and fascinating, troubling and intrigu- ing. He not only assails democratic practice but also weaves hesitations about the reach of that attack into the very presentation of his thought. A substantial measure of ambivalence, not unequivocal hostility, marks his attitude toward democracy as he knew it. This dimension of Plato's thought has remained largely unexplored for some time. This is in part because Plato has for centuries been cast as a founding ®gure in what has been called the ªantidemocratic tradition in Western thought.º2 But even when commentators have noted that state- 1 This view is longstanding and widely held, and thus I call it canonical. Typical are pas- sages such as the following: ªPlato's antipathy to democracy as he knew it thus emerges clearly in this section [the simile of the ship at Republic 487b±497a]. No doubt his anti- democratic attitude is a product of various complex factors, but what should interest us here is the philosophical ground for his condemnation of democracyº (R.