Ancient and Modern Concepts of the Rule Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GREEKS BETWEEN EAST and WEST GREEKS BETWEEN EAST and WEST Essays in Greek Literature and History

PUBLICATIONS OF THE ISRAEL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND HUMANITIES SECTION OF HUMANITIES GREEKS BETWEEN EAST AND WEST GREEKS BETWEEN EAST AND WEST Essays in Greek Literature and History in Memory of David Asheri edited by Gabriel Herman and Israel Shatzman Jerusalem 2007 The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities ISBN 965-208-170-1 © The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 2007 Typesetting: Judith Sternberg Printed in Israel Contents Gabriel Herman and Preface 7 Israel Shatzman Alexander Uchitel The Earliest Tyrants: From Luwian Tarwanis to Greek TÚranno$ 13 Margalit Finkelberg Mopsos and the Philistines: Mycenaean Migrants in the Eastern Mediterranean 31 Rachel Zelnick-Abramovitz Lies Resembling Truth: On the Beginnings of Greek Historiography 45 Deborah Levine Gera Viragos, Eunuchs, Dogheads, and Parrots in Ctesias 75 Daniela Dueck When the Muses Meet: Poetic Quotations in Greek Historiography 93 Ephraim David Myth and Historiography: Lykourgos 115 Gabriel Herman Rituals of Evasion in Ancient Greece 136 Gocha R. Tsetskhladze Greeks and Locals in the Southern Black Sea Littoral: A Re-examination 160 The Writings of David Asheri: A Bibliographical Listing 197 PREFACE According to a well-known Greek proverb, the office reveals the character of the statesman (Arche deixei andra). One could argue by the same token that the bibliography reveals the character of the intellectual. There are few people to whom this would apply more aptly than the man commemorated in this volume. David Asheri (1925–2000) was a dedicated scholar who lived for his work, and his personality was immersed in his writings. This brief preface will therefore focus on his literary output, eschewing as much as possible reference to his private or public life – to which he would anyhow have objected. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

On Values, Culture and the Classics — and What They Have in Common

REVIEW ARTICLES On Values, Culture and the Classics — and What They Have in Common Gabriel Herman Ralph Μ. Rosen and Ineke Sluiter (eds.), Valuing Others in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne Supplements 323. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2010. Pp. xii + 476. ISBN 9789004189218. $224.00. 1 The editors of this collection of articles, the fifth in the series “Penn-Leiden Colloquia on Ancient Values”, have embarked on an enterprise whose troublesomeness might not have been evident right at the beginning. They set out to re-frame, and then re-examine, the ancient Greek and Roman evaluative concepts and terminology pertaining to trust, fairness, and social cohesion (or, as they put it, ‘the idea that people “belong together”, as a family, a group, a polis, a community, or just as fellow human beings’, 5), in light of the rapidly evolving fields of the social and life sciences. The opening paragraph of the introduction, which elaborates Ralph Rosen’s and Ineke Sluiter’s aim, appears to be a bold and welcome departure from the formulation of aims in a long gallery of published books on ancient morality and values. I quote it in full, warning that it may appear abstruse to scholars whose routine reading does not exceed the bounds of classics: The scale of human societies has expanded dramatically since the origin of our species. From small kin-based communities of hunter-gatherers human beings have become used to large-scale societies that require trust, fairness, and cooperative behaviour even among strangers. Recent research has suggested that such norms are not just a relic from our stone-age psychological make-up, when we only had to deal with our kin-group and prosocial behaviour would thus have had obvious genetic benefits, but that over time new social norms and informal institutions were developed that enabled successful interactions in larger (even global) settings. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law. -

REVIEW ARTICLES Periclean Athens

REVIEW ARTICLES Periclean Athens Gabriel Herman Lorel J. Samons II (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Pericles . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. xx + 343 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-00389-6 (paperback); 978-0-521-80793-7 (hardback). This companion to the age of Pericles, dated roughly 450-428 B.C., brings together eleven articles by a distinguished gallery of specialists, its declared aim being ‘to provoke as much as to inform, to stimulate the reader to further inquiry rather than to put matters to rest’ (xvii). Even though these specialists do not always see eye to eye in their judgments, their discord does not normally surface in the essays, and the end result is a coherent overview of Athenian society which succeeds in illuminating an important chapter of Greek history. This evaluation does not however apply to the book’s ‘Introduction’ and especially not to its ‘Conclusion’ (‘Pericles and Athens’), written by the editor himself. Here Samons, rather than weaving the individual contributions into a general conclusion, restates assessments of Athenian democracy that he has published elsewhere (see 23 n. 73). These are often at odds with most previous evaluations of Periclean Athens and read more like exhortations to praiseworthy behavior than historical analyses. In this review article I will comment briefly on the eleven chapters and then return to Samons’ views, my more general theme being the issue of historical judgment. Reminding us that democracy and empire often appear as irreconcilable opposites to the modern mind, Peter Rhodes in his dense, but remarkably lucid Chapter 1 (‘Democracy and Empire’) addresses the question of the relationship between Athens’ democracy and fifth-century empire. -

Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A. Bruegger Follow this and additional works at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation John A. Bruegger, Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 081 (2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM, LEGALITY, AND THE RULE OF LAW JOHN A. BRUEGGER ABSTRACT There are numerous interactions between the rule of law and the concept of freedom. We can see this by looking at Fuller’s eight principles of legality, the positive and negative theories of liberty, coercive and empowering laws, and the formal and substantive rules of law. Adherence to the rules of formal legality promotes freedom by creating stability and predictability in the law, on which the people can then rely to plan their behaviors around the law—this is freedom under the law. Coercive laws can actually promote negative liberty by pulling people out of a Hobbesian state of nature, and then thereafter can be seen to decrease negative liberty by restricting the behaviors that a person can perform without receiving a sanction. Empowering laws promote negative freedom by creating new legal abilities, which the people can perform. -

A Government of Laws, Not Of

A Government of Laws, Not of Men American Democracy and The Rule of Law Introduction The strength of our democratic institutions relies on the public’s understanding of those institutions. However, we are not preparing Californians with the civic knowledge and skills they need to be active and engaged participants. This white paper is intended to provide concise and accessible context to the understanding of “the rule of law,” and its relevance to the daily lives of individuals. The first of three sections defines the concept of “the rule of law” and provides the historical development from a Western perspective. The second briefly discusses the implementation of “the rule of law” in other countries and jurisdictions, and highlights some of the differences between the United States and countries abroad. While the third underscores the relevance of “the rule of law” to Californians by briefly discussing California’s turbulent past, and modern day advantages to a stable legal system that have helped to create a thriving economy in the great State of California. What is the Rule of Law? The concept of “the rule of law” can be a difficult one to define in specific terms. This section will attempt to assert a general definition of “the rule of law” and provide some context to the development of that definition historically and culturally. Finally, this section covers how “the rule of law” is implemented by the government with a focus on the judicial branch and its interactions with the executive and legislative branches. Overview of the Modern Conception of the Rule of Law A modern view in the United States is that through the separation of powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches “that it may be a government of laws and not of men.” 1 This perspective extends to create a system of government where individuals and the government itself are subject to laws that are administered with equity, and neither are subject to 1 Mass. -

Qt04h0308g.Pdf

UC Berkeley Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift Title Biography and Bibliography of T. G. Rosenmeyer (1920-2007) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04h0308g Publication Date 2007-04-05 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California TOM ROSENMEYER IN MEMORIAM Saturday, April 7, 2007, 1 p.m. Heyns Room The Faculty Club University of California, Berkeley PROGRAM MUSICAL SELECTIONS OPENING REMARKS: Tony Long REMEMBRANCES Robert Alter Erich Gruen John Prausnitz Michelle Zerba Kathy Fabunan MUSICAL INTERLUDE REMEMBRANCES Patricia Rosenmeyer Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Donald Mastronarde Mark Griffith CLOSING REMARKS: Tony Long RECEPTION THOMAS GUSTAV ROSENMEYER APRIL 3, 1920–FEBRUARY 6, 2007 Tom Rosenmeyer, Professor Emeritus of Greek and Comparative Literature at the University of California at Berkeley, died at his home in Oakland on Tuesday, February 6, 2007. He was 86. Born in Hamburg, Germany, on April 3, 1920, and educated at the humanistic Johanneum Gymnasium in that city from 1930 to 1938, Tom fled to England in 1939 to avoid Nazi per- secution. He enrolled at the London School of Oriental Studies, intending to learn Sanskrit, but in 1940 the British, expecting a German invasion, interned all “enemy” aliens. He was sent on to an internment camp in Canada, where the residents formed their own impromptu “university,” studying Hebrew, Sanskrit, and Arabic as well as the classical languages together behind barbed wire. Among his colleagues in the camp were future classicist Martin Ostwald and Emil Fackenheim, who taught Tom Arabic and later became a prominent philosopher of the Shoah. Released from internment in 1942, Tom completed an undergraduate degree in Classics at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, in 1944 and took an MA in Classics at the University of Toronto in 1945 before proceeding to Harvard for his doctoral studies. -

104 BOOK REVIEWS Volume Is Significant As It Puts the Act of Reading Herodotus in the Spotlight

104 BOOK REVIEWS volume is significant as it puts the act of reading Herodotus in the spotlight. Eran Almagor The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Polly Low, Interstate Relations in Classical Greece . Morality and Power , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. 313 pp. ISBN 978-0-521-87206-5. This book, which owes its origin to a Cambridge Ph.D. thesis, employs theoretical approaches from the field of International Relations (hereafter IR) to challenge the widely held view that Greek interstate relations and diplomatic practices were excessively unrestrained, anarchic and violent, and that the contemporary theories of interstate behavior were correspondingly under- developed and unsophisticated. Polly Low (hereafter L.) contends that, quite to the contrary, during the period under examination (roughly 479-322 B.C.), a developed normative framework did exist, which shaped the conduct and representation of interstate relations and was underpinned by complex thinking. She concedes, however, that this thinking did not amount to the sort of highly developed IR theories that exist in modern times. L. starts her presentation with a survey of the dilemmas and debates that accompanied the formation of IR as an academic discipline in modern times. In the wake of World War I, the so- called “idealists” believed that a liberal state of mind could supersede pure military power in the conduct of interstate relations and serve as a basis for a stable world order. The conspicuous failure of the brainchild of this conception, the League of Nations, seemed however to vindicate the claim of their rival “realists”, who held that moral considerations were and should be irrelevant to the study of relations between states, as these are, and were, dominated by nothing but naked force. -

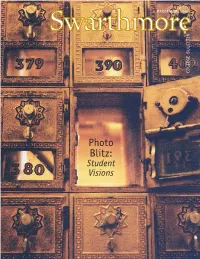

Swarthmore College Bulletin (December 2002)

DECEMBER 2002 Photo Blitz: Student Visions ON THE COVER: B DAN FAIRCHILD’S [’03] PHOTOGRAPH OF PARRISH HALL MAILBOXES GRACES THE APRIL 2003 PAGE OF NEXT YEAR’S SWARTHMORE COLLEGE CALENDAR. IT IS ONE OF THOUSANDS OF PHOTOS SUBMITTED DURING THIS FALL’S “PHOTO BLITZ,” SPONSORED BY THE PUBLICATIONS OFFICE. FOR MORE STUDENT VISIONS OF SWARTHMORE, TURN TO PAGE 20. CONTENTS: HANG NGO ’05, ONE OF MORE THAN 360 STUDENTS WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE PHOTO BLITZ, SAID OF THIS PHOTO: “THE SHADOWS ARE [ONES] OF ME AND ... MY BEST FRIEND HERE, FRANCISCO CASTRO ’05 [LEFT].” DECEMBERDECEMBER 2002 2002 F e a t u r e s Cell Divisions 14 Swarthmore-educated scientists, ethicists, and legal scholars help Departments lead the stem-cell and cloning debate. L e t t e r s 3 Readers’ feedback By Tom Krattenmaker P r o f i l e s C o l l e c t i o n 4 Working Toward Through Student Current news a Better World 48 E y e s 2 0 Sam Ashelman ’37 hosted Bosnian A weeklong “Photo Blitz” reveals diplomats at Coolfont Resort.Resort students’ vision of Swarthmore. Alumni Digest 42 Connections and adventures By Elizabeth Redden ’05 By Jeffrey Lott ClassNotes 44 F o l l o w i n g Liberal Arts Correspondence from friends t h e W i n d 6 4 in a Conservative Jon Lyman ’77 enjoys the scenery L a n d 2 6 and sociability of ballooning. Two Swarthmoreans help start D e a t h s 5 3 a women’s college in Jeddah, Sympathy extended By Angela Doody Saudi Arabia.