Honor Brabazon (Ed.). Neoliberal Legality: Understanding the Role of Law in the Neoliberal Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2003 Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law Alan Schwartz Robert E. Scott Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Contracts Commons Recommended Citation Alan Schwartz & Robert E. Scott, Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law, 113 YALE L. J. 541 (2003). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/339 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Article Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law Alan Schwartz* and Robert E. Scottt* CONTENTS I. IN TROD U CTION ................................................................................. 543 II. JUSTIFYING AN EFFICIENCY THEORY OF CONTRACT ........................ 550 A . W hat Firms M axim ize .................................................................. 550 B. Why the State Should Help Firms ................................................ 555 III. THE ENFORCEMENT FUNCTION ........................................................ 556 A. Enforcement Often Is Unnecessary.............................................. 557 B. EncouragingRelation-Specific Investment .................................. 559 C. -

4000 Contract Law: General Theories

4000 CONTRACT LAW: GENERAL THEORIES Richard Craswell Professor of Law, Stanford Law School © Copyright 1999 Richard Craswell Abstract When contracts are incomplete, the law must rely on default rules to resolve any issues that have not been explicitly addressed by the parties. Some default rules (called ‘majoritarian’ or ‘market-mimicking’) are designed to be left in place by most parties, and thus are chosen to reflect an efficient allocation of rights and duties. Others (called ‘information-forcing’ or ‘penalty’ default rules) are designed not to be left in place, but rather to encourage the parties themselves to explicitly provide some other resolution; these rules thus aim to encourage an efficient contracting process. This chapter describes the issues raised by such rules, including their application to heterogeneous markets and to separating and pooling equilibria; it also briefly discusses some non- economic theories of default rules. Finally, this chapter also discusses economic and non-economic theories about the general question of why contracts should be enforced at all. JEL classification: K12 Keywords: Contracts, Incomplete Contracts, Default Rules 1. Introduction This chapter describes research bearing on the general aspects of contract law. Most research in law and economics does not explicitly address these general aspects, but instead proceeds directly to analyze particular rules of contract law, such as the remedies for breach. That body of research is described below in Chapters 4100 through 4800. There is, however, some scholarship on the general nature of contract law’s ‘default rules’, or the rules that define the parties’ obligations in the absence of any explicit agreement to the contrary. -

Positivism and the Separation of Law and Economics

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 1996 Positivism and the Separation of Law and Economics Avery W. Katz Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation Avery W. Katz, Positivism and the Separation of Law and Economics, 94 MICH. L. REV. 2229 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/610 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POSITIVISM AND THE SEPARATION OF LAW AND ECONOMICS Avery Wiener Katz* INTRODUCION The modem field of law and economics - that is, the application of economic analysis to legal subjects other than trade and business reg- ulation - is now over thirty years old, but it remains controversial in the legal academy and, to a lesser extent, in the profession at large. Since its beginnings in the early 1960s, the economic approach has pro- voked substantial opposition and antagonism. The sources of this resis- tance, however, are a matter of dispute. Many economists and economi- cally influenced lawyers attribute it to more traditional lawyers' reluctance to learn a new and unfamiliar set of concepts and techniques. Critics of the economic approach offer a variety of other explanations. Some are skeptical of the utility of abstract theoretical modeling in the social sciences,' others object to economics' central behavioral assump- tion of rational choice,2 still others criticize economics' supposed liber- tarian politics and ideological allegiance to laissez-faire. -

Law and Political Economy in a Time of Accelerating Crises

Angela P. Harris, School of Law, UC Davis James J. (“Jay”) Varellas III, Department of Political Science, UC Berkeley* Introduction: Law and Political Economy in a Time of Accelerating Crises Abstract In this time of accelerating crises nationally and worldwide, conventional understandings of the relationships among state, market, and society and their regulation through law are inadequate. In this Editors’ Introduction to Volume 1, Issue 1 of the Journal of Law and Political Economy, we reflect on our current historical moment, identify genealogies of the Law and Political Economy (LPE) project, articulate some of the intellectual foundations of the work, and finally discuss the journal’s institutional history and context. Keywords: Law and Political Economy I. Introduction Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises contains this famous exchange: “How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.” In the United States and around the world, we are facing intertwined crises: skyrocketing economic inequality, an increasingly destabilizing and extractive system of global finance, dramatic shifts in the character of work and economic production, a crisis of social reproduction, the ongoing disregard of Black and brown lives, the rise of new authoritarianisms, a global pandemic, and, of course, looming above all, the existential threat of global climate change. From the vantage point of mid-2020, it is impossible to avoid the sense that these crises, like Mike’s bankruptcy, have emerged both suddenly and as the result of problems long in the making. It is also clear that these interlocking crises are accelerating as they collide with societies whose capacities to respond have been hollowed out by decades of neoliberalism. -

1 FTC Perspectives on the Use of Econometric Analyses in Antitrust

FTC Perspectives on the Use of Econometric Analyses in Antitrust Cases∗ David Scheffman and Mary Coleman1 I. Introduction This paper discusses our perspectives, as FTC economists and experienced litigation economists, on how to make econometric analyses more useful in antitrust investigations and litigation. We first briefly discuss the role of econometrics and empirical analyses generally in antitrust. Sound empirical analyses can (and should) provide important evidence in an antitrust investigation or litigation. Based on our experience at the FTC and as litigation economists, we then suggest “best practices” for developing econometric studies that will be useful to the FTC in its decision making. We also provide some examples of the types of useful econometric analyses that are frequently conducted in FTC investigations. Finally, expanding on some the issues raised in the recent FTC working paper,2 we discuss the use of scanner data for demand estimation, the use of merger simulation models, and the use of manufacturer level data in consumer products cases. A. Quantitative Analyses, Generally Before discussing econometric analyses, we begin with a more general perspective on quantitative analyses. Some of the most important issues in antitrust cases often hinge on quantitative evidence (e.g., levels and trends in prices, market shares, sales, margins, profitability, and shipment patterns). These types of quantitative analyses are often very important and frequently do not involve statistical/econometric analyses. We begin with this basic point because although there has been much attention in recent years to the use of formal modeling and econometric estimation in antitrust, we should not lose sight of the fact that quantitative analyses of various kinds are useful. -

Labor Law, Antitrust Law, and Economics Professors' Comment

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Boston College Law School Faculty Papers 1-14-2019 Labor Law, Antitrust Law, and Economics Professors' Comment on the National Labor Relations Board's Proposed Joint-Employer Rule Hiba Hafiz Boston College Law School, [email protected] Brishen Rogers Temple University Beasley School of Law, [email protected] Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Kate Bronfenbrenner Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/lsfp Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Hiba Hafiz, Brishen Rogers, Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt, and Kate Bronfenbrenner. "Labor Law, Antitrust Law, and Economics Professors' Comment on the National Labor Relations Board's Proposed Joint-Employer Rule." (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law School Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Labor Law, Antitrust Law, and Economics Professors’ Comment on the National Labor Relations Board’s Proposed Joint-Employer Rule January 14, 2019 Submitted via www.regulations.gov John F. Ring, Chairman National Labor Relations Board 1015 Half Street, SE Washington, D.C. 20570-0001 Attn: Roxanne Rothschild, -

Law-And-Political-Economy Framework: Beyond the Twentieth-Century Synthesis Abstract

JEDEDIAH BRITTON- PURDY, DAVID SINGH GREWAL, AMY KAPCZYNSKI & K. SABEEL RAHMAN Building a Law-and-Political-Economy Framework: Beyond the Twentieth-Century Synthesis abstract. We live in a time of interrelated crises. Economic inequality and precarity, and crises of democracy, climate change, and more raise significant challenges for legal scholarship and thought. “Neoliberal” premises undergird many fields of law and have helped authorize policies and practices that reaffirm the inequities of the current era. In particular, market efficiency, neu- trality, and formal equality have rendered key kinds of power invisible, and generated a skepticism of democratic politics. The result of these presumptions is what we call the “Twentieth-Century Synthesis”: a pervasive view of law that encases “the market” from claims of justice and conceals it from analyses of power. This Feature offers a framework for identifying and critiquing the Twentieth-Century Syn- thesis. This is also a framework for a new “law-and-political-economy approach” to legal scholar- ship. We hope to help amplify and catalyze scholarship and pedagogy that place themes of power, equality, and democracy at the center of legal scholarship. authors. The authors are, respectively, William S. Beinecke Professor of Law at Columbia Law School; Professor of Law at Berkeley Law School; Professor of Law at Yale Law School; and Associate Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School and President, Demos. They are cofounders of the Law & Political Economy Project. The authors thank Anne Alstott, Jack Balkin, Jessica Bulman- Pozen, Corinne Blalock, Angela Harris, Luke Herrine, Doug Kysar, Zach Liscow, Daniel Markovits, Bill Novak, Frank Pasquale, Robert Post, David Pozen, Aziz Rana, Kate Redburn, Reva Siegel, Talha Syed, John Witt, and the participants of the January 2019 Law and Political Economy Work- shop at Yale Law School for their comments on drafts at many stages of the project. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

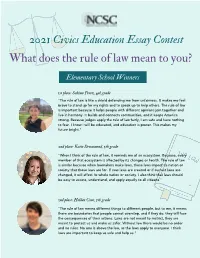

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law. -

Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A. Bruegger Follow this and additional works at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation John A. Bruegger, Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 081 (2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM, LEGALITY, AND THE RULE OF LAW JOHN A. BRUEGGER ABSTRACT There are numerous interactions between the rule of law and the concept of freedom. We can see this by looking at Fuller’s eight principles of legality, the positive and negative theories of liberty, coercive and empowering laws, and the formal and substantive rules of law. Adherence to the rules of formal legality promotes freedom by creating stability and predictability in the law, on which the people can then rely to plan their behaviors around the law—this is freedom under the law. Coercive laws can actually promote negative liberty by pulling people out of a Hobbesian state of nature, and then thereafter can be seen to decrease negative liberty by restricting the behaviors that a person can perform without receiving a sanction. Empowering laws promote negative freedom by creating new legal abilities, which the people can perform.