Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and Country Reports

Flash Report 01/2017 Flash Reports on Labour Law January 2017 Summary and country reports EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate DG Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Unit B.2 – Working Conditions Flash Report 01/2017 Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017 ISBN ABC 12345678 DOI 987654321 © European Union, 2017 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Flash Report 01/2017 Country Labour Law Experts Austria Martin Risak Daniela Kroemer Belgium Wilfried Rauws Bulgaria Krassimira Sredkova Croatia Ivana Grgurev Cyprus Nicos Trimikliniotis Czech Republic Nataša Randlová Denmark Natalie Videbaek Munkholm Estonia Gaabriel Tavits Finland Matleena Engblom France Francis Kessler Germany Bernd Waas Greece Costas Papadimitriou Hungary Gyorgy Kiss Ireland Anthony Kerr Italy Edoardo Ales Latvia Kristine Dupate Lithuania Tomas Davulis Luxemburg Jean-Luc Putz Malta Lorna Mifsud Cachia Netherlands Barend Barentsen Poland Leszek Mitrus Portugal José João Abrantes Rita Canas da Silva Romania Raluca Dimitriu Slovakia Robert Schronk Slovenia Polonca Končar Spain Joaquín García-Murcia Iván Antonio Rodríguez Cardo Sweden Andreas Inghammar United Kingdom Catherine Barnard Iceland Inga Björg Hjaltadóttir Liechtenstein Wolfgang Portmann Norway Helga Aune Lill Egeland Flash Report 01/2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................. -

Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense

63 Section 7: Criminal Offense, Criminal Responsibility, and Commission of a Criminal Offense Article 15: Criminal Offense A criminal offense is an unlawful act: (a) that is prescribed as a criminal offense by law; (b) whose characteristics are specified by law; and (c) for which a penalty is prescribed by law. Commentary This provision reiterates some of the aspects of the principle of legality and others relating to the purposes and limits of criminal legislation. Reference should be made to Article 2 (“Purpose and Limits of Criminal Legislation”) and Article 3 (“Principle of Legality”) and their accompanying commentaries. Article 16: Criminal Responsibility A person who commits a criminal offense is criminally responsible if: (a) he or she commits a criminal offense, as defined under Article 15, with intention, recklessness, or negligence as defined in Article 18; IOP573A_ModelCodes_Part1.indd 63 6/25/07 10:13:18 AM 64 • General Part, Section (b) no lawful justification exists under Articles 20–22 of the MCC for the commission of the criminal offense; (c) there are no grounds excluding criminal responsibility for the commission of the criminal offense under Articles 2–26 of the MCC; and (d) there are no other statutorily defined grounds excluding criminal responsibility. Commentary When a person is found criminally responsible for the commission of a criminal offense, he or she can be convicted of this offense, and a penalty or penalties may be imposed upon him or her as provided for in the MCC. Article 16 lays down the elements required for a finding of criminal responsibility against a person. -

Four Models of the Criminal Process Kent Roach

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 89 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter Winter 1999 Four Models of the Criminal Process Kent Roach Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Kent Roach, Four Models of the Criminal Process, 89 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 671 (1998-1999) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/99/8902-0671 THM JOURNAL OF QMINAL LAW& CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 89, No. 2 Copyright 0 1999 by Northwestem University. School of Law Psisd in USA. CRIMINOLOGY FOUR MODELS OF THE CRIMINAL PROCESS KENT ROACH* I. INTRODUCTION Ever since Herbert Packer published "Two Models of the Criminal Process" in 1964, much thinking about criminal justice has been influenced by the construction of models. Models pro- vide a useful way to cope with the complexity of the criminal pro- cess. They allow details to be simplified and common themes and trends to be highlighted. "As in the physical and social sciences, [models present] a hypothetical but coherent scheme for testing the evidence" produced by decisions made by thousands of actors in the criminal process every day.2 Unlike the sciences, however, it is not possible or desirable to reduce the discretionary and hu- manistic systems of criminal justice to a single truth. -

The Relationship Between Capitalism and Democracy

The Relationship Between Capitalism And Democracy Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Petkovic, Aleksandra Evelyn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 12:57:19 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625122 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CAPITALISM AND DEMOCRACY By ALEKSANDRA EVELYN PETKOVIC ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors degree With Honors in Philosophy, Politics, Economics, and Law THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA M A Y 2 0 1 7 Approved by: ____________________________ Dr. Thomas Christiano Department of Philosophy Abstract This paper examines the very complex relationship between capitalism and democracy. While it appears that capitalism provides some necessary element for a democracy, a problem of political inequality and a possible violation of liberty can be observed in many democratic countries. I argue that this political inequality and threat to liberty are fueled by capitalism. I will analyze the ways in which capitalism works against democratic aims. This is done through first illustrating what my accepted conception of democracy is. I then continue to depict how the various problems with capitalism that I describe violate this conception of democracy. This leads me to my conclusion that while capitalism is necessary for a democracy to reach a certain needed level of independence from the state, capitalism simultaneously limits a democracy from reaching its full potential. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

National Honor Society Liberty High School Chapter LHS Chapter of The

National Honor Society Liberty High School Chapter 1115 Linden Street Bethlehem, PA 18018 LHS Chapter of the National Honor Society A pplication Criteria and Requirements Criteria to Receive an Application: Students must have a 3.75 cumulative GPA at the end of their Sophomore or Junior year to receive an application at the beginning of their Junior or Senior year, respectively. How to Apply: Students will receive an application packet at the beginning of the school year in which they are eligible (Junior or Senior year). The application must be completely filled out and returned on the due date in September. The sections are as follows: Section I - Community Service Juniors applying must have at least 30 hours of community service completed (ie: 15 hours/year). Seniors applying must have at least 45 hours completed It is recommended that students complete all 60 hours of community service prior to applying at a minimum Section II - Essay Statement Demonstrate how you plan to incorporate the four pillars of the National Honor Society into your future experiences and endeavors: F our Pillars: I. Scholarship II: Leadership III: Service IV: Character Section III - Leadership Positions List any/all leadership positions you feel may be appropriate. The more positions listed, the better Section IV - Structured Extracurricular Activities/Work List any/all activities you feel are relevant. The more activities listed, the better. Section V - Teacher Recommendations Requirements Once Accepted: Attendance ALL meetings are mandatory unless otherwise noted. If you fail to come to a meeting without an excuse, you will have a meeting with Mr. -

5. What Matters Is the Motive / Immanuel Kant

This excerpt is from Michael J. Sandel, Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do?, pp. 103-116, by permission of the publisher. 5. WHAT MATTERS IS THE MOTIVE / IMMANUEL KANT If you believe in universal human rights, you are probably not a utili- tarian. If all human beings are worthy of respect, regardless of who they are or where they live, then it’s wrong to treat them as mere in- struments of the collective happiness. (Recall the story of the mal- nourished child languishing in the cellar for the sake of the “city of happiness.”) You might defend human rights on the grounds that respecting them will maximize utility in the long run. In that case, however, your reason for respecting rights is not to respect the person who holds them but to make things better for everyone. It is one thing to con- demn the scenario of the su! ering child because it reduces overall util- ity, and something else to condemn it as an intrinsic moral wrong, an injustice to the child. If rights don’t rest on utility, what is their moral basis? Libertarians o! er a possible answer: Persons should not be used merely as means to the welfare of others, because doing so violates the fundamental right of self-ownership. My life, labor, and person belong to me and me alone. They are not at the disposal of the society as a whole. As we have seen, however, the idea of self-ownership, consistently applied, has implications that only an ardent libertarian can love—an unfettered market without a safety net for those who fall behind; a 104 JUSTICE minimal state that rules out most mea sures to ease inequality and pro- mote the common good; and a celebration of consent so complete that it permits self-in" icted a! ronts to human dignity such as consensual cannibalism or selling oneself into slav ery. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

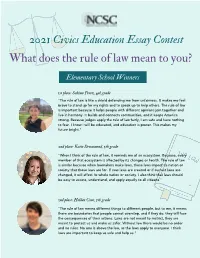

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Introduction to Law and Legal Reasoning Law Is

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO LAW AND LEGAL REASONING LAW IS "MAN MADE" IT CHANGES OVER TIME TO ACCOMMODATE SOCIETY'S NEEDS LAW IS MADE BY LEGISLATURE LAW IS INTERPRETED BY COURTS TO DETERMINE 1)WHETHER IT IS "CONSTITUTIONAL" 2)WHO IS RIGHT OR WRONG THERE IS A PROCESS WHICH MUST BE FOLLOWED (CALLED "PROCEDURAL LAW") I. Thomas Jefferson: "The study of the law qualifies a man to be useful to himself, to his neighbors, and to the public." II. Ask Several Students to give their definition of "Law." A. Even after years and thousands of dollars, "LAW" still is not easy to define B. What does law Consist of ? Law consists of enforceable rule governing relationships among individuals and between individuals and their society. 1. Students Need to Understand. a. The law is a set of general ideas b. When these general ideas are applied, a judge cannot fit a case to suit a rule; he must fit (or find) a rule to suit the unique case at hand. c. The judge must also supply legitimate reasons for his decisions. C. So, How was the Law Created. The law considered in this text are "man made" law. This law can (and will) change over time in response to the changes and needs of society. D. Example. Grandma, who is 87 years old, walks into a pawn shop. She wants to sell her ring that has been in the family for 200 years. Grandma asks the dealer, "how much will you give me for this ring." The dealer, in good faith, tells Grandma he doesn't know what kind of metal is in the ring, but he will give her $150. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law.