The Franklin Stereotype: the Spiritual-Secular Gospels of Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abou T B En Fran Klin

3 Continuing Eventsthrough December 31,2006 January 17– March 15, 2006 LEAD SPONSOR B F o O u f O o nding Father nding r KS 1 In Philadelphia EVERYONE IS READING about Ben Franklin www.library.phila.gov The Autobiography Ben and Me Franklin: The Essential of Benjamin Franklin BY ROBERT LAWSON Founding Father RBY BENeJAMIN FRAsNKLIN ource BY JAGMES SRODES uide One Book, One Philadelphia The Books — Three Books for One Founding Father In 2006, One Book, One Philadelphia is joining Ben Franklin 300 Philadelphia to celebrate the tercentenary (300 years) of Franklin’s birth. Franklin’s interests were diverse and wide-ranging. Countless volumes have been written about him. The challenge for the One Book program was to choose works that would adequately capture the true essence of the man and his times. Because of the complexity of this year’s subject, and in order to promote the widest participation possible, One Book, One Philadelphia has chosen to offer not one, but three books about Franklin. This year’s theme will be “Three Books for One Founding Father.” The featured books are: • The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin (various editions) • Ben and Me by Robert Lawson (1939, Little, Brown & Company) • Franklin: The Essential Founding Father by James Srodes (2002, Regnery Publishing, Inc.) The Authors BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, author of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, was born in 1706 and died in 1790 at the age of 84. He was an author, inventor, businessman, scholar, scientist, revolutionary, and statesman whose contributions to Philadelphia and the world are countless. -

MCMANUS-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (4.095Mb)

The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McManus, Stuart Michael. 2016. The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493519 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World A dissertation presented by Stuart Michael McManus to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Stuart Michael McManus All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: James Hankins, Tamar Herzog Stuart Michael McManus The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World Abstract Historians have long recognized the symbiotic relationship between learned culture, urban life and Iberian expansion in the creation of “Latin” America out of the ruins of pre-Columbian polities, a process described most famously by Ángel Rama in his account of the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada). This dissertation argues that this was part of a larger global process in Latin America, Iberian Asia, Spanish North Africa, British North America and Europe. -

Amazingmrfranklin.Pdf

TheThe Amazing r.r. ranklin or The Boy Who Read Everything To Ernie —R.A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2004 by Ruth Ashby Illustrations © 2004 by Michael Montgomery All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Composition by Melanie McMahon Ives Paintings created in oil on canvas Text typeset in SWFTE International’s Bronte; titles typeset in Luiz da Lomba’s Theatre Antione Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth. The amazing Mr. Franklin / written by Ruth Ashby.-- 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: Introduces the life of inventor, statesman, and founding father Benjamin Franklin, whose love of books led him to establish the first public library in the American colonies. ISBN 978-1-56145-306-1 1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790--Juvenile literature. 2. Statesmen--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 3. Scientists--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 4. Inventors--United States-- Biography--Juvenile literature. 5. Printers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. [1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790. 2. Statesmen. 3. Scientists. 4. Inventors. 5. Printers.] I. Title. E302.6.F8A78 2004 973.3'092--dc22 -

Proverbs Are the Best Policy

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2005 Proverbs are the Best Policy Wolfgang Mieder Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mieder, W. (2005). Proverbs are the best policy: Folk wisdom and American politics. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolfgang Mieder Proverbs are the Best Policy Folk Wisdom and American Politics Proverbs Are the Best Policy Proverbs Are the Best Policy Folk Wisdom and American Politics Wolfgang Mieder Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2005 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress/ Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mieder, Wolfgang. Proverbs are the best policy : folk wisdom and American politics / Wolfgang Mieder. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-0-87421-622-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-87421-622-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. United States--Politics and government--Miscellanea. 2. United States--Politics and government--Quotations, maxims, etc. 3. Proverbs, American. 4. Proverbs--Political aspects--United States. 5. Rhetoric --Political aspects--United States. 6. Politicians--United States --Language. I. Title. E183.M54 2005 398.9’21’0973--dc22 2005018275 Dedicated to PATRICK LEAHY and JIM JEFFORDS U.S. -

Benjamin Franklin 1 Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin 1 Benjamin Franklin Benjamin Franklin 6th President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania In office October 18, 1785 – December 1, 1788 Preceded by John Dickinson Succeeded by Thomas Mifflin 23rd Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly In office 1765–1765 Preceded by Isaac Norris Succeeded by Isaac Norris United States Minister to France In office 1778–1785 Appointed by Congress of the Confederation Preceded by New office Succeeded by Thomas Jefferson United States Minister to Sweden In office 1782–1783 Appointed by Congress of the Confederation Preceded by New office Succeeded by Jonathan Russell 1st United States Postmaster General In office 1775–1776 Appointed by Continental Congress Preceded by New office Succeeded by Richard Bache Personal details Benjamin Franklin 2 Born January 17, 1706 Boston, Massachusetts Bay Died April 17, 1790 (aged 84) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Nationality American Political party None Spouse(s) Deborah Read Children William Franklin Francis Folger Franklin Sarah Franklin Bache Profession Scientist Writer Politician Signature [1] Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706 [O.S. January 6, 1705 ] – April 17, 1790) was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. As a scientist, he was a major figure in the American Enlightenment and the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. He invented the lightning rod, bifocals, the Franklin stove, a carriage odometer, and the glass 'armonica'. He formed both the first public lending library in America and the first fire department in Pennsylvania. -

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin by Dr. Mark Canada This article originally appeared in the Encyclopedia of American Literature, 2008. “. I began to suspect that this Doctrine tho’ it might be true, was not very useful.” Life Benjamin Franklin, in the words of biographer Carl Van Doren, was a “harmonious human multitude.” As Van Doren's assessment suggests, Franklin’s life and work are at once difficult and simple to summarize. On the one hand, his multitude of contributions to the worlds of printing, journalism, literature, science, and politics defy brief summary. On the other hand, these many accomplishments were in harmony with one another, sharing a common theme of human progress through human initiative. More than any other American, Franklin personified the Age of Enlightenment, a time when humans were growing more aware of their world and inventing ways to control it for their benefit. His Enlightenment perspective shines through his literature, which includes some of the most important works to appear in America in the eighteenth century. Over more than six decades, he produced an enormous and varied body of work, including the best- selling Poor Richard’s Almanack, literary hoaxes such as “A Witch Trial at Mount Holly” and “The Speech of Miss Polly Baker,” satires such as “An Edict by the King of Prussia,” humorous sketches such as “The Ephemera” and “The Elysian Fields,” and informational pieces such as “Information to Those Who Would Remove to America,” as well as countless news articles, letters, scientific reports, and proposals related to civic affairs. His masterpiece, The Autobiography, is one of the classic books of American literature. -

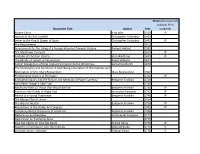

Document Title Author Year Status (S-Tentatively Seleced; IP-In Progress) Magna Carta King John 1215 IP Journal of the First

Status (S-tentatively seleced; IP-in Document Title Author Year progress) Magna Carta King John 1215 IP Journal of the first Landfall Christopher Columbus 1492 Letter to the King & Queen of Spain Christopher Columbus 1492 IP The Requirement 1513 Inducements for the Liking of a Voyage Intended Towards Virginia Richard Hakluyt 1585 The Mayflower Compact 1620 IP A Model of Christian Charity John Winthrop 1630 IP The Bloody of Tenent of Persecution Roger Williams 1644 A Brief Recognition of New-England’s Errand into the Wilderness Samuel Danforth 1670 The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson Mary Rowlandson 1682 Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges 1701 IP A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of Paper Currency Benjamin Franklin 1729 John Peter Zenger's Libel Trial 1735 Necessary Hints to Those That Would be Rich Benjamin Franklin 1736 IP Sinners in the Hands of Angry God Johnathan Edwards 1741 IP Advice to a Young Tradesman Benjamin Franklin 1748 IP The Albany Plan of Union 1754 The Way to Wealth Benjamin Franklin 1758 IP Resolutions of the Stamp Act Congress 1765 IP Testimony Before the House of Commons Benjamin Franklin 1766 Declaration and Resolves Continental Congress 1774 Declaration on Taking Up Arms 1775 Give Me Liberty Or Give Me Death Patrick Henry 1775 IP Speech on Conciliation with the Colonies Edmund Burke 1775 S Common Sense , selection Thomas Paine 1776 S Status (S-tentatively seleced; IP-in Document Title Author Year progress) Declaration of Independence Thomas Jefferson 1776 IP Letter to John Adams Abigail Adams 1776 S Virginia Constitution 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights 1776 Articles of Confederation 1777 S A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge Thomas Jefferson 1779 S Sentiments of an American Woman Esther Reed 1780 Hector St. -

Chapter 5: Unrest in the Colonies

In London, Benjamin Franklin stated the American view on British taxes: "They will oppose it to the last. They do not consider it as at all necessary for you to raise money . by your taxes . America has been greatly misrepresented . (as) refusing to bear any part of (the war's) expense. The Colonies . paid and clothed near 25,000 men during the last war, a number equal to (that of) Britain." -----in an interview before The House Of Commons, 1766 What do you think Benjamin Franklin is trying to say? How do the colonists feel about the taxes? Write your response in your notebook. revenue = incoming money resolution = a formal expression of opinion boycott = to refuse to buy items from a particular country repeal = to cancel an act or law effigy = rag figure representing an unpopular individual prohibit = stop; disallow violate = disturb or disregard After the French & Indian war: • Britain gained control of a lot of territory in North America. Needed to protect its land & people. Passed The Proclamation Of 1763: 1. prohibited (prevented) colonists expanding West 2. controlled people in a contained area 3. avoid conflict with Native Americans 4. controlled fur trade in the frontier https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pxp bjyYCBmA Britain planned to station over 10,000 troops in the newly acquired land to protect their interests: $$$$$ Needed revenue (incoming $) to pay for it Taxed the colonists HEAVILY Taxes were strictly enforced = some people tried to find ways around the taxes (smuggled goods) Britain passed Writs Sugar Act: Of Assistance -

In Poor Richard's Almanack

Politics and Ideology in Poor Richard's Almanack HE * * ^T^ GREATEST MONARCH on the proudest Throne, is * * I obliged to sit upon his own Arse," Poor Richard re- JL minds us in his almanac for 1737.1 Such a truism might pass unnoticed except as a bit of humor. However, it serves as a sign of Benjamin Franklin's political and ideological agenda in preparing his annual collection of proverbs, anecdotes, astrological charts, and miscellaneous information. Besides urging us to be virtuous, diligent, and frugal, Franklin was doing something with his almanacs that only Philadelphia's William Birkett seems to have done previously. He proclaimed the superiority of the common man who practiced those precepts to his putative betters, and urged common men to assume roles in the "public sphere" and shape their own destinies. Poor Rich- ard went further by responding to changes in the Pennsylvania political scene from 1733 to 1758, choosing his stories to persuade his readers to adopt his views on public affairs. Thus, in both their general socio- political outlook and their opinions on particular public events, the almanacs illustrated Franklin's own efforts toward shaping the mental- ity of a provincial society that purchased thousands of Poor Richards. The author wishes to thank Peter Eisenstadt and John Frantz for their helpful suggestions. Members of the Colloquium of the Institute of Early American History and Culture and the Philadelphia Center for Early American Studies, too numerous to cite gave much valuable advice when earlier versions of this essay were presented in September and October 1991. -

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, by Benjamin Franklin This Ebook Is for the Use of Anyone Anywhere at No Cost and with Almost No Restrictions Whatsoever

Benjamin Franklin, by Benjamin Franklin 1 Benjamin Franklin, by Benjamin Franklin Project Gutenberg's Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, by Benjamin Franklin This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin Author: Benjamin Franklin Editor: Frank Woodworth Pine Illustrator: E. Boyd Smith Release Date: December 28, 2006 [EBook #20203] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN *** Benjamin Franklin, by Benjamin Franklin 2 Produced by Turgut Dincer, Brian Sogard and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net [Illustration: FRANKLIN ARMS] [Illustration: FRANKLIN SEAL] [Illustration: Franklin at the Court of Louis XVI "He was therefore, feasted and invited to all the court parties. At these he sometimes met the old Duchess of Bourbon, who, being a chess player of about his force, they very generally played together. Happening once to put her king into prize, the Doctor took it. 'Ah,' says she, 'we do not take kings so.' 'We do in America,' said the Doctor."--Thomas Jefferson.] AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN WITH ILLUSTRATIONS by E. BOYD SMITH EDITED by FRANK WOODWORTH PINE [Illustration: Printers Mark] New York HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1916 Copyright, 1916, BY HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY June, 1922 THE QUINN & BODEN CO. PRESS RAHWAY, N. J. CONTENTS Introduction vii The Autobiography I. Ancestry and Early Life in Boston 3 II. -

The Unfinished Life of Benjamin Franklin Anderson, Douglas

The Unfinished Life of Benjamin Franklin Anderson, Douglas Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Anderson, Douglas. The Unfinished Life of Benjamin Franklin. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.13866. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/13866 [ Access provided at 29 Sep 2021 15:56 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The Unfinished Life of Benjamin Franklin This page intentionally left blank The unfinished life of Benjamin Franklin douglas anderson The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore © 2012 The Johns Hopkins University Press All rights reserved. Published 2012 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 9876543 2 i The Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Anderson, Douglas, 1950– The unfinished life of Benjamin Franklin / Douglas Anderson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13 978-1-4214-0523-0 (hdbk: acid-free paper) isbn-10 1-4214-0523-7 (hdbk: acid-free paper) isbn-13: 978-1-4214-0613-8 (electronic) isbn-10: 1-4214-0613-6 (electronic) 1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706–1790. Autobiography. 2. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706–1790. 3. Statesmen—United States—Biography. I. Title. e302.6.f8a58 2012 973.3'092—dc23 [B] 2011040332 A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or [email protected]. -

Mr. Franklin-PB Cover.Indd 1 9/19/18 1:22 PM the Amazing Mr

Middle reader historical fiction Ashby www.peachtree-online.com The Amazing Ben Franklin hated working in his brother’s print shop. He wanted his freedom immediately. But he couldn’t Mr. Frank stay in Boston, where everyone knew him. lin Ruth Ashby He would have to run away. Where could he go? Ben wondered. New York, perhaps. T But he needed money to pay for the long journey. he A There was only one answer. He would have to sell his mazing most treasured possessions—his books! M “An attractive and highly readable r. F account of Franklin’s life.” ranklin —Booklist ❖ NCSS/CBC Notable Social Studies Trade Books for Young People 978-1-68263-102-7 $7.95 The Amazing Mr. Franklin-PB Cover.indd 1 9/19/18 1:22 PM The Amazing Mr. Franklin Mr. Franklin-Interior.indd 1 9/25/18 2:04 PM To Ernie -R. A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2004 by Ruth Ashby First trade paperback edition published in 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Book design and composition by Adela Pons Printed in October 2018 in the United States of America by RR Donnelley & Sons in Harrisonburg, Virginia 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 (hardcover) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 (trade paperback) HC ISBN: 978-1-56145-306-1 PB ISBN: 978-1-68263-102-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth.