In Poor Richard's Almanack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN Norman, Oklahoma 2009 SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ________________________ Prof. Paul A. Gilje, Chair ________________________ Prof. Catherine E. Kelly ________________________ Prof. Judith S. Lewis ________________________ Prof. Joshua A. Piker ________________________ Prof. R. Richard Hamerla © Copyright by ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN 2009 All Rights Reserved. To my excellent and generous teacher, Paul A. Gilje. Thank you. Acknowledgements The only thing greater than the many obligations I incurred during the research and writing of this work is the pleasure that I take in acknowledging those debts. It would have been impossible for me to undertake, much less complete, this project without the support of the institutions and people who helped me along the way. Archival research is the sine qua non of history; mine was funded by numerous grants supporting work in repositories from California to Massachusetts. A Friends Fellowship from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies supported my first year of research in the Philadelphia archives and also immersed me in the intellectual ferment and camaraderie for which the Center is justly renowned. A Dissertation Fellowship from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History provided months of support to work in the daunting Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. The Chandis Securities Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens brought me to San Marino and gave me entrée to an unequaled library of primary and secondary sources, in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth. -

Notes on the Almanacs of Massachusetts

1912.] Almmmcs of Massachusetts. 15 NOTES ON THE ALMANACS OF MASSACHUSETTS. BY CHARLES L. NICHOLS The origin of the almanac is wrapped in as much obscurity as that of the science of astronomy upon which its usefulness depends. It is possible, however, to trace some of the steps of its evolution and to note the uses to which it has been applied as that evolution has taken place. « When Fabius, the secretary of Appius Claudius, stole the fasti-sacri or Kalendares of the Roman priest- hood three hundred years before Christ, and exhibited the white tablets on the walls of the Forum, he not only struck a blow for reUgious freedom, but also gave to the people a long coveted source of information. Until that period no fast or holy-day had been pro- claimed except by the decision of the priests, since by their secret methods were made the calculations for those days. From that time the calendar of days has belonged to the people themselves, and has held an important position in the almanac of all nations. When Ptolemy in 150, A. D., prepared his catalogue of stars, and laid the foundation for more exact and con- tinuous records of their movements, the development of the Ephemeris, or daily note-book of the planets' places in our almanacs was assured. The meaning of the "man of signs," which is still so commonly seen, was minutely described by Manil- ius in his Astronomicon, written in the reign of the Emperor Tiberius. Origen and Jamblicus state that the principle underlying this belonged to a much earlier 16 American Aritiquarian Society. -

Towson University Office of Graduate Studies Emerging

TOWSON UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF GRADUATE STUDIES EMERGING NATIONAL IDENTITY IN PRE‐REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA by Anneliese Johnson A thesis presented to the faculty of Towson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Social Science Towson University 8000 York Road Towson, MD 21252 May 2013 Acknowledgements It is only with the help and support of many wonderful people that I was able to complete my thesis successfully. First, Dr. Paul McCartney displayed remarkable patience during my most difficult moments, and was able to continually move me forward, even when I was unsure about where to go. His honest appraisal of my work, and advice regarding content, style, and time management, among many things, was invaluable, and I am incredibly grateful for his willingness to teach me. I am honored to have had him as the chairman of my thesis committee. To Dr. Bruce Mortenson, I owe a great deal of gratitude for the insight and advice offered throughout the thesis process. His encouragement, enthusiasm, and accessibility helped me stay calm and kept me focused on the next step, every step of the way. He continues to epitomize Rom Brafman’s notion of the ‘satellite.’ I am also grateful to Dr. Steven Phillips, not only for sitting on my thesis committee, but also for sparking my interest in nationalism as an undergraduate, and continuing to foster that interest at the graduate level by always indulging my questions and search for answers. Additionally, I am indebted to Dr. Alison McCartney, for her encouragement and understanding throughout this process, and also for always sharing her chocolate. -

Biographies Page 1 of 2

Pearson Prentice Hall: Biographies Page 1 of 2 Biographies Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) "They that can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety." —Historical Review of Pennsylvania , 1759 One of Benjamin Franklin's contemporaries, the French economist Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, once described Franklin's remarkable achievements in the following way: "He snatched the lightning from the skies and the sceptre from tyrants." Printer The son of a Boston soap- and candle-maker, Benjamin Franklin had little formal education, but he read widely and practiced writing diligently. He was apprenticed to his brother, a printer, at the age of 12. Later, he found work as a printer in Philadelphia. Courtesy Library of Congress By the time he was 20, Franklin and a partner owned a company that printed the paper currency of Pennsylvania. Franklin also published a newspaper and, from 1732 to 1757, his famous Poor Richard's Almanac . Public Service Franklin was always interested in improving things, from the way people lived lives to the way they were governed. In 1727, he founded the Junto, a society that debated questions of the day. This, in turn, led to the establishment of a library association and a volunteer fire company in Philadelphia. He was also instrumental in founding the University of Pennsylvania. In addition, Franklin spent time conducting scientific experiments involving electricity and inventing useful objects, such as the lightning rod, an improved stove, and bifocals. Franklin was also active in politics. He served as clerk of the Pennsylvania legislature and postmaster of Philadelphia, and he organized the Pennsylvania militia. -

Abou T B En Fran Klin

3 Continuing Eventsthrough December 31,2006 January 17– March 15, 2006 LEAD SPONSOR B F o O u f O o nding Father nding r KS 1 In Philadelphia EVERYONE IS READING about Ben Franklin www.library.phila.gov The Autobiography Ben and Me Franklin: The Essential of Benjamin Franklin BY ROBERT LAWSON Founding Father RBY BENeJAMIN FRAsNKLIN ource BY JAGMES SRODES uide One Book, One Philadelphia The Books — Three Books for One Founding Father In 2006, One Book, One Philadelphia is joining Ben Franklin 300 Philadelphia to celebrate the tercentenary (300 years) of Franklin’s birth. Franklin’s interests were diverse and wide-ranging. Countless volumes have been written about him. The challenge for the One Book program was to choose works that would adequately capture the true essence of the man and his times. Because of the complexity of this year’s subject, and in order to promote the widest participation possible, One Book, One Philadelphia has chosen to offer not one, but three books about Franklin. This year’s theme will be “Three Books for One Founding Father.” The featured books are: • The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin (various editions) • Ben and Me by Robert Lawson (1939, Little, Brown & Company) • Franklin: The Essential Founding Father by James Srodes (2002, Regnery Publishing, Inc.) The Authors BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, author of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, was born in 1706 and died in 1790 at the age of 84. He was an author, inventor, businessman, scholar, scientist, revolutionary, and statesman whose contributions to Philadelphia and the world are countless. -

MCMANUS-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (4.095Mb)

The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McManus, Stuart Michael. 2016. The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493519 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World A dissertation presented by Stuart Michael McManus to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Stuart Michael McManus All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: James Hankins, Tamar Herzog Stuart Michael McManus The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World Abstract Historians have long recognized the symbiotic relationship between learned culture, urban life and Iberian expansion in the creation of “Latin” America out of the ruins of pre-Columbian polities, a process described most famously by Ángel Rama in his account of the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada). This dissertation argues that this was part of a larger global process in Latin America, Iberian Asia, Spanish North Africa, British North America and Europe. -

In the Polite Eighteenth Century, 1750–1806 A

AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Elizabeth E. Webster Christopher Hamlin, Director Graduate Program in History and Philosophy of Science Notre Dame, Indiana April 2010 © Copyright 2010 Elizabeth E. Webster AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 Abstract by Elizabeth E. Webster In this thesis, I will examine the promotion of science, or “useful knowledge,” in the polite eighteenth century. Historians of England and America have identified the concept of “politeness” as a key component for understanding eighteenth-century culture. At the same time, the term “useful knowledge” is also acknowledged to be a central concept for understanding the development of the early American scientific community. My dissertation looks at how these two ideas, “useful knowledge” and “polite character,” informed each other. I explore the way Americans promoted “useful knowledge” in the formative years between 1775 and 1806 by drawing on and rejecting certain aspects of the ideal of politeness. Particularly, I explore the writings of three central figures in the early years of the American Philosophical Society, David Rittenhouse, Charles Willson Peale, and Benjamin Rush, to see how they variously used the language and ideals of politeness to argue for the promotion of useful knowledge in America. Then I turn to a New Englander, Thomas Green Fessenden, who identified and caricatured a certain type of man of science and satirized the late-eighteenth-century culture of useful knowledge. -

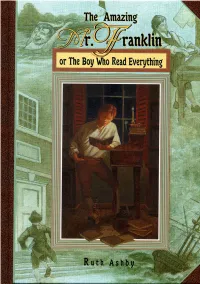

Amazingmrfranklin.Pdf

TheThe Amazing r.r. ranklin or The Boy Who Read Everything To Ernie —R.A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2004 by Ruth Ashby Illustrations © 2004 by Michael Montgomery All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Composition by Melanie McMahon Ives Paintings created in oil on canvas Text typeset in SWFTE International’s Bronte; titles typeset in Luiz da Lomba’s Theatre Antione Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth. The amazing Mr. Franklin / written by Ruth Ashby.-- 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: Introduces the life of inventor, statesman, and founding father Benjamin Franklin, whose love of books led him to establish the first public library in the American colonies. ISBN 978-1-56145-306-1 1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790--Juvenile literature. 2. Statesmen--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 3. Scientists--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 4. Inventors--United States-- Biography--Juvenile literature. 5. Printers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. [1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790. 2. Statesmen. 3. Scientists. 4. Inventors. 5. Printers.] I. Title. E302.6.F8A78 2004 973.3'092--dc22 -

Franklin's Accounts 1745, Calendar 3 1 Introduction. Though

Franklin's Accounts 1745, Calendar 3 1 Introduction. Though inconclusive evidence may suggest that Franklin owned a slave before 1745, the accounts prove that he did by the summer of 1745: on 14 Aug, Charles Moore charged Franklin 15.0. "To a Racoon hat for your Negro" and on 21 Dec Franklin paid Moore "To dressing a hat for your Negro." BF’s sister Elizabeth Douse appears, 14 Nov. On 12 Oct, BF bought the other half of a lot (site of the present 318 Market Street) from John Croker, the son-in-law of Sarah Read, Deborah’s mother. She had left half the lot (9 April 1734) jointly to her daughters Deborah Franklin and Frances Croker. Frances had died in 1740 and shortly after, John Croker moved to New York. Now Croker sold his half-interest to BF for £80. A receipt for 26 March leaves no mystery as to what Franklin paid for ground rent on his Arch Street property (see 1 Aug 1741): "Receiv'd of Benjamin Franklin Three Pounds, Seven Shillings, 3.7.0., which (with one Years Gazette) is in full for the Rent of his Lot between Arch Street & Appletree Alley to this Day per me, Christopher Thompson." Equally revealing is a receipt from Franklin's partner, David Hall, "Receiv'd of Benj. Franklin at Sundry Times, Cash, Forty four Pounds to this Day, which with my Diet, &c. to the 20th of June past Twenty-Six pounds, makes in all, Seventy Pounds." Though Franklin seems never to have brought suit against anyone for outstanding debts, he did involve himself, albeit indirectly, in litigation on 9 Dec: "Receiv'd of Benjamin Franklin on Account of Richard Pitts (for whom I was special Bail in a Suit commenc'd against said Pitts by Mr. -

Proverbs Are the Best Policy

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2005 Proverbs are the Best Policy Wolfgang Mieder Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mieder, W. (2005). Proverbs are the best policy: Folk wisdom and American politics. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wolfgang Mieder Proverbs are the Best Policy Folk Wisdom and American Politics Proverbs Are the Best Policy Proverbs Are the Best Policy Folk Wisdom and American Politics Wolfgang Mieder Utah State University Press Logan, Utah Copyright © 2005 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322–7800 www.usu.edu/usupress/ Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mieder, Wolfgang. Proverbs are the best policy : folk wisdom and American politics / Wolfgang Mieder. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-0-87421-622-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-87421-622-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. United States--Politics and government--Miscellanea. 2. United States--Politics and government--Quotations, maxims, etc. 3. Proverbs, American. 4. Proverbs--Political aspects--United States. 5. Rhetoric --Political aspects--United States. 6. Politicians--United States --Language. I. Title. E183.M54 2005 398.9’21’0973--dc22 2005018275 Dedicated to PATRICK LEAHY and JIM JEFFORDS U.S. -

On the Culture of Print in Antebellum Augusta, Georgia 1828-1860

i Informing the South: On the Culture of Print in Antebellum Augusta, Georgia 1828-1860 By Jamene Brenton Stewart A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library & Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 05/22/12 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor Library & Information Studies Louise Robbins, Emeritus Professor, Library & Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library & Information Studies/Journalism and Mass Communication Susan E. Lederer, Professor, Medical History & Bioethics Jonathan Daniel Wells, Professor, History, Temple University ii © Jamene Brenton Stewart 2012 All Rights Reserve i Dedication This dissertation is decided to my grandparents Thomas and Lenora Bartley-Stewart, my great-aunts Birdie Sartor and Sister Minnie. I stand proudly on your shoulders. ii Acknowledgements To Dr. Jessie J. Walker mi compañero, chief council, and friend, I thank you for your unyielding support in all of my endeavors. How apt that you are a Hawkeye and I a Badger. I thank my advisor Professor Christine Pawley, who has worked with me on this project since year one of my doctoral studies. This work would not have been possible without your guidance and expertise. Additionally sincere thanks to my dissertation committee, Professors Louise Robbins, Greg Downey, Susan Lederer and Jonathan D. Wells. I must thank the American Antiquarian Society, which has helped transform me into a print culture historian. I will be forever grateful of the financial support I received from the Society, Isaiah Thomas Scholarship and Stephen Botein Fellowship, but most importantly the opportunity the AAS provided for me to interact with fascinating documents and meet amazing scholars; a special thanks to Drs. -

The Franklin Stereotype: the Spiritual-Secular Gospels of Four

THE FRANKLIN STEREOTYPE: THE SPIRITUAL-SECULAR GOSPELS OF FOUR NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN AUTHORS A Dissertation by J.D. ISIP Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University-Commerce in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2015 THE FRANKLIN STEREOTYPE: THE SPIRITUAL-SECULAR GOSPELS OF FOUR NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN AUTHORS A Dissertation by J.D. ISIP Approved by: Advisor: Karen Roggenkamp Committee: Susan Louise Stewart Christopher Thomas Gonzalez Yvonne Villanueva-Russell Head of Department: Hunter Hayes Dean of the College: Salvatore Attardo Dean of Graduate Studies: Arlene Horne iii Copyright © 2015 Jomar Daniel Isip iv ABSTRACT THE FRANKLIN STEREOTYPE: THE SPIRITUAL-SECULAR GOSPELS OF FOUR NINETEENTH-CENTURY AMERICAN AUTHORS J.D. Isip, PhD Texas A&M University-Commerce, 2015 Advisor: Karen Roggenkamp, PhD The purpose of this study was to examine the spiritual-secular influences of Benjamin Franklin and his Autobiography found in the selected novels of four nineteenth-century American authors: Fanny Fern’s Ruth Hall, A Domestic Tale of the Present Time; Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Work, A Story of Experience; Horatio Alger, Jr.’s Ragged Dick or, Street Life in New York with Boot Blacks; and Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Specifically, I examined three areas of influence: navigation of a print market demanding both secular and spiritual plotlines; creation of “secular saints” who borrow spiritual iconography for secular journeys and goals; and the dissemination of “secular gospels” or social change messages couched in religious language. These areas of influence form what I call the Franklin Stereotype.