Benjamin Franklin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fanlight | January-February 2011

THE FANLIGHT Vol. 21, No. 6 Monroe County Historical Association January - February 2011 Happy 175th Birthday, Monroe County! Amy Leiser, Executive Director On April 1, 1836, after nine long years of debate and discussion, created the The House created the Fulton County bill and sent the bill Monroe County was formed from pieces of land cut from to the Senate, where it failed. In 1835, the Fulton County bill was Northampton County and southern Pike County. Although settled by again resurrected, but it failed to receive the necessary number of some of the earliest-arriving European colonists, Monroe County was votes. Other petitions for names for the new county included not one of the earliest-formed counties in Pennsylvania. It was the “Evergreen” County, for the many conifer trees and “Jackson” County 53rd recognized county out of 67 statewide. Years before its official after President Andrew Jackson. Neither of these names, however, recognition as a separate entity, residents living in this developing received enough support for adoption. area petitioned the legislature to create the new county. It is unclear how exactly the name “Monroe” was suggested for the Joseph Ritner, the Governor of Pennsylvania from 1835 to 1839, with new county, but it is clear that it is an Act by the Pennsylvania General Assembly, acknowledged that named for President James Monroe. the area known as “north of the Blue Mountains of Northampton James Monroe was the fifth president County” had been settled for long enough and that its population had of the United States. He served as a grown enough to be considered an independent county. -

Ben and Us . . . Sparking the Standards

Disseminator’s Name: Gloria S. Block E-Mail Address: [email protected] School Address and Telephone: P.S. 42 380 Genesee Avenue Staten Island, NY 10312 (718) 984-3800 Program Title: Ben and Us . Sparking the Standards For more information, contact: Teachers Network IMPACT II Program Attn: Peter A. Paul 285 West Broadway New York, NY 10013 (212) 966-5582 Fax: (212) 941-1787 E-mail: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.teachersnetwork.org Ben and Us . Sparking the Standards TABLE OF CONTENTS Program Overview …………………………………….. Target Student Age/Level Major Goals Timelines Types of Assessments Lessons and Activities ………………………….………….. Part 1: Who was Benjamin Franklin? Part 2: Reading and Teaching the Novel, “Ben and Me.” Part 3: Research Report: A Famous Scientist or Inventor Part 4: Writing an Original Story . “The Inventor/Scientist and Me” Sample Worksheets ……………………………………….. ? $100 Dollar Bill Graphic Organizer ? Student Guide – Reading Response Literature Log ? Poor Richard’s Almanack Lesson and Student Handout ? Rubric for Literature Activities Resource List ………………………………………………. Bibliography ………………………………………………… Student Work Samples …………………………….……… ? ? Literature Response Log entries for Chapter 4 ? ? Essays on maxims from Poor Richard’s Almanack ? ? Literature extensions and culminating activities ? ? Outline of Chapter 7: The Scientific Method ? ? Research Reports ? ? Draft of story in process ? ? Original story PROGRAM OVERVIEW Target Student Age/Level This program has been used with fifth grade students, in a self- contained classroom. It could be adapted in grades 6 – 8, and implemented by Communication Arts, Social Studies, Science and Computer teachers as an integrated curriculum learning experience. Major Goals Benjamin Franklin said, “The doors of wisdom are never shut.” A mouse named Amos can help open those doors of wisdom and contribute knowledge, creativity and fun to a classroom. -

Spring/Summer 2019 Vol. 33 Number 2 Newsletter of the Bucks County

Newsletter of the Bucks County Historical Society SprinG/SummerFall 2020 2019 VOL.Vol. 3433 NumberNUMBER 21 Smithsonian Aliate TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Executive Director ............................3 Smithsonian Aliate Welcome Back to the Mercer Museum & Fonthill Castle ..........4 Board of Trustees Virtual Support in Extraordinary Times ..........................4 OFFICERS Bucks County in the Pandemic: Sharing Your Stories .............5 Board Chair Heather A. Cevasco Vice-Chair Maureen B. Carlton Vice-Chair Linda B. Hodgdon New Event Tent at the Mercer Museum ..........................5 Treasurer Thomas L. Hebel Secretary William R. Schutt Past Chair John R. Augenblick Collections Connection ..........................................6 TRUSTEES 200 Years of Bucks County Art ...................................7 Kelly Cwiklinski Gustavo I. Perea David L. Franke Michael B. Raphael Christine Harrison Jonathan Reiss Museum’s Art Collection Spans Three Centuries ..................8 Verna Hutchinson Jack Schmidt Michael S. Keim Susan J. Smith William D. Maeglin Patricia Taglioloni Museum’s Art Collection Spans Three Centuries Cont ............9 Charles T. McIlhinney Jr. Tom Thomas Jeff Paduano Rochelle Thompson Recent Acquisitions ........................................... Richard D. Paynton, Jr. Steven T. Wray 10 Michelle A. Pedersen Funding Received for Fonthill Castle Tile Project ..............11 Trustee Emeritus Elizabeth H. Gemmill Recent Acquisitions (cont). ....................................11 President & Executive Director -

Benjamin Franklin (10 Vols., New York, 1905- 7), 5:167

The American Aesthetic of Franklin's Visual Creations ENJAMIN FRANKLIN'S VISUAL CREATIONS—his cartoons, designs for flags and paper money, emblems and devices— Breveal an underlying American aesthetic, i.e., an egalitarian and nationalistic impulse. Although these implications may be dis- cerned in a number of his visual creations, I will restrict this essay to four: first, the cartoon of Hercules and the Wagoneer that appeared in Franklin's pamphlet Plain Truth in 1747; second, the flags of the Associator companies of December 1747; third, the cut-snake cartoon of May 1754; and fourth, his designs for the first United States Continental currency in 1775 and 1776. These four devices or groups of devices afford a reasonable basis for generalizations concerning Franklin's visual creations. And since the conclusions shed light upon Franklin's notorious comments comparing the eagle as the emblem of the United States to the turkey ("a much more respectable bird and withal a true original Native of America"),1 I will discuss that opinion in an appendix. My premise (which will only be partially proven during the fol- lowing discussion) is that Franklin was an extraordinarily knowl- edgeable student of visual symbols, devices, and heraldry. Almost all eighteenth-century British and American printers used ornaments and illustrations. Many printers, including Franklin, made their own woodcuts and carefully designed the visual appearance of their broad- sides, newspapers, pamphlets, and books. Franklin's uses of the visual arts are distinguished from those of other colonial printers by his artistic creativity and by his interest in and scholarly knowledge of the general subject. -

Benjamin Franklin People Mentioned in Walden

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN BENJAMIN “VERSE-MAKERS WERE GENERALLY BEGGARS” FRANKLIN1 Son of so-and-so and so-and-so, this so-and-so helped us to gain our independence, instructed us in economy, and drew down lightning from the clouds. “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Franklin was distantly related to Friend Lucretia Mott, as was John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Adams, and Octavius Brooks Frothingham. HDT WHAT? INDEX THE PEOPLE OF WALDEN: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN WALDEN: In most books, the I, or first person, is omitted; in this PEOPLE OF it will be retained; that, in respect to egotism, is the main WALDEN difference. We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking. I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well. Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience. BENJAMIN FRANKLIN WALDEN: But all this is very selfish, I have heard some of my PEOPLE OF townsmen say. I confess that I have hitherto indulged very little WALDEN in philanthropic enterprises. I have made some sacrifices to a sense of duty, and among others have sacrificed this pleasure also. There are those who have used all their arts to persuade me to undertake the support of some poor family in town; and if I had nothing to do, –for the devil finds employment for the idle,– I might try my hand at some such pastime as that. -

Ben and Me Ben and Me Ben and Me

Ben and Me Ben and Me Independent Contract Ben and Me Independent Contract by Robert Lawson Name:___________________________ Number of activities to be completed: _______ Name:___________________________ Number of activities to be completed: _______ Writing About the Book 1. Writing 2. 7. Science 8. Science The life of Benjamin Franklin, one of the most Amos feels he and Ben need a written contract Ben Franklin had many famous friends, including When Amos changes some of the Tide Table important men in colonial times, is recorded in Ben and George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. numbers in Poor Richard’s Almanack, he does An inventor’s motivation is usually a desire to that clearly states their responsibilities. First, solve a problem. Benjamin Franklin’s home was Me by his close friend and associate Amos the mouse. they discuss their needs, and then they write Research the life of Ben Franklin to find not realize the problem it will cause. Later, Author Robert Lawson claims to have been given information about three of his friends. Then create when he and Ben are awakened by an angry freezing cold, which prompted him to invent the the contract. Amos wants food, shelter, and Franklin stove. He also invented a chair that Amos’s tiny journals in which Amos boasts of being the protection for himself and his family. Ben wants a booklet about Ben and his friends. Obtain four mob of Shipmasters whose ships have all run wisdom behind this famous man. Amos, under the cover sheets of white paper. Write the title “Ben and aground, he understands the importance of the converted into a stepladder and bifocal glasses advice and assistance from Amos. -

05-06 Annual Report TERCE NTEN NIAL ANNIVERSARY of the BIRTH of PENN’S FOUNDER

05-06 Annual Report TERCE NTEN NIAL ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIRTH OF PENN’S FOUNDER “ Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.” – Benjamin Franklin University of Pennsylvania Nondiscrimination Statement The University of Pennsylvania values diversity and seeks talented students, faculty and staff from diverse backgrounds. The University of Pennsylvania does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, color, national or ethic origin, age, dis- ability, or status as a Vietnam Era Veteran or disabled veteran in the administration of educational policies, programs or activities; admissions policies; scholarship and loan awards; athletic, or other University administered programs or employment. Questions or complaints regarding this policy should be directed to: Executive Director, Office of Affirmative Action and Equal Opportunity Programs, Sansom Place East, 3600 Chestnut Street, Suite 228, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6106 or by phone at (215) 898-6993 (Voice) or (215) 898-7803 (TDD). Table of Contents Message from the Vice President for Finance and Treasurer 5 Endowment and Investments 24 Management Responsibility for Financial Statements 29 Report of Independent Accountants 30 Statement of Financial Position 31 Statement of Activities 32 Statement of Cash Flows 33 Notes to Financial Statements 34 Trustees 52 Statutory Officers 53 Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston in 1706. At 17, he settled in Philadelphia, where he began his lifelong quest to serve humanity. A printer by trade, Franklin was also an inventor, innovator, statesman, philanthropist, writer and visionary. As a statesman, he represented Pennsylvania at the revolutionary meetings that resulted in the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. -

Abou T B En Fran Klin

3 Continuing Eventsthrough December 31,2006 January 17– March 15, 2006 LEAD SPONSOR B F o O u f O o nding Father nding r KS 1 In Philadelphia EVERYONE IS READING about Ben Franklin www.library.phila.gov The Autobiography Ben and Me Franklin: The Essential of Benjamin Franklin BY ROBERT LAWSON Founding Father RBY BENeJAMIN FRAsNKLIN ource BY JAGMES SRODES uide One Book, One Philadelphia The Books — Three Books for One Founding Father In 2006, One Book, One Philadelphia is joining Ben Franklin 300 Philadelphia to celebrate the tercentenary (300 years) of Franklin’s birth. Franklin’s interests were diverse and wide-ranging. Countless volumes have been written about him. The challenge for the One Book program was to choose works that would adequately capture the true essence of the man and his times. Because of the complexity of this year’s subject, and in order to promote the widest participation possible, One Book, One Philadelphia has chosen to offer not one, but three books about Franklin. This year’s theme will be “Three Books for One Founding Father.” The featured books are: • The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin (various editions) • Ben and Me by Robert Lawson (1939, Little, Brown & Company) • Franklin: The Essential Founding Father by James Srodes (2002, Regnery Publishing, Inc.) The Authors BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, author of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, was born in 1706 and died in 1790 at the age of 84. He was an author, inventor, businessman, scholar, scientist, revolutionary, and statesman whose contributions to Philadelphia and the world are countless. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory

Form No. ^0-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Independence National Historical Park AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 313 Walnut Street CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT t Philadelphia __ VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE PA 19106 CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE 2LMUSEUM -BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE X-UNOCCUPIED —^COMMERCIAL 2LPARK .STRUCTURE 2EBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —XEDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE -SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS -OBJECT —IN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED ^GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: REGIONAL HEADQUABIER REGION STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE PHILA.,PA 19106 VICINITY OF COURTHOUSE, ____________PhiladelphiaREGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. _, . - , - , Ctffv.^ Hall- - STREET & NUMBER n^ MayTftat" CITY. TOWN STATE Philadelphia, PA 19107 TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL CITY. TOWN CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED 2S.ORIGINALSITE _GOOD h^b Jk* SANWJIt's ALTERED _MOVED DATE. —FAIR _UNEXPOSED Description: In June 1948, with passage of Public Law 795, Independence National Historical Park was established to preserve certain historic resources "of outstanding national significance associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States." The Park's 39.53 acres of urban property lie in Philadelphia, the fourth largest city in the country. All but .73 acres of the park lie in downtown Phila-* delphia, within or near the Society Hill and Old City Historic Districts (National Register entries as of June 23, 1971, and May 5, 1972, respectively). -

MCMANUS-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (4.095Mb)

The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation McManus, Stuart Michael. 2016. The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493519 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World A dissertation presented by Stuart Michael McManus to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Stuart Michael McManus All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisors: James Hankins, Tamar Herzog Stuart Michael McManus The Global Lettered City: Humanism and Empire in Colonial Latin America and the Early Modern World Abstract Historians have long recognized the symbiotic relationship between learned culture, urban life and Iberian expansion in the creation of “Latin” America out of the ruins of pre-Columbian polities, a process described most famously by Ángel Rama in his account of the “lettered city” (ciudad letrada). This dissertation argues that this was part of a larger global process in Latin America, Iberian Asia, Spanish North Africa, British North America and Europe. -

Ben Franklin: Highlighting the Printer

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS ECONOMIC EDUCATION Ben Franklin: Highlighting the Printer Lesson Author Jeannette Bennett, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis–Memphis Branch Standards and Benchmarks (see page 24) Lesson Description In this lesson, students will learn that money is an invention. They will read and analyze an essay focusing primarily on one aspect of Ben Franklin’s life—his work as a printer— and how he was an inventor and entrepreneur who also promoted the use of currency in the United States. Students will cite specific textual evidence regarding problems and solutions and will answer questions and complete a timeline. By using evidence and information gleaned from text, students will write a fictitious social-media post defending the selection of Ben Franklin’s portrait for the $100 note. Grade Level 5-8 Time Required 90-120 minutes Concepts Currency Entrepreneur Entrepreneurship Human capital Money Profit Timeline ©2012, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Permission is granted to reprint or photocopy this lesson in its entirety for educational purposes, provided the user credits the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, www.stlouisfed.org/education_resources. 1 Lesson Plan Ben Franklin: Highlighting the Printer Objectives Students will be able to • differentiate between an inventor and an entrepreneur; • define entrepreneur, entrepreneurship, money, and profit; • define human capital; • explain how an investment in human capital can affect a person’s productivity and income; • identify portraits on U.S. currency; • identify important events in Ben Franklin’s printing career; • describe Ben Franklin’s entrepreneurial behaviors; • identify problems and solutions noted in an essay; and • defend the placement of Ben Franklin’s portrait on the $100 note. -

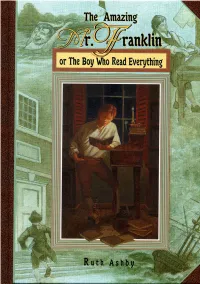

Amazingmrfranklin.Pdf

TheThe Amazing r.r. ranklin or The Boy Who Read Everything To Ernie —R.A. Published by PEACHTREE PUBLISHERS 1700 Chattahoochee Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30318-2112 www.peachtree-online.com Text © 2004 by Ruth Ashby Illustrations © 2004 by Michael Montgomery All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmit- ted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Book design by Loraine M. Joyner Composition by Melanie McMahon Ives Paintings created in oil on canvas Text typeset in SWFTE International’s Bronte; titles typeset in Luiz da Lomba’s Theatre Antione Printed in China Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ashby, Ruth. The amazing Mr. Franklin / written by Ruth Ashby.-- 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: Introduces the life of inventor, statesman, and founding father Benjamin Franklin, whose love of books led him to establish the first public library in the American colonies. ISBN 978-1-56145-306-1 1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790--Juvenile literature. 2. Statesmen--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 3. Scientists--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. 4. Inventors--United States-- Biography--Juvenile literature. 5. Printers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. [1. Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790. 2. Statesmen. 3. Scientists. 4. Inventors. 5. Printers.] I. Title. E302.6.F8A78 2004 973.3'092--dc22