In the Polite Eighteenth Century, 1750–1806 A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Education Forum

The newsletter for the Education Section of the BSHS No 42 Education February 2004 Forum Edited by Martin Monk 32, Rainville Road, Hammersmith, London W6 9HA Tel: 0207-385-5633. e-mail: [email protected] Contents Editorial 1 Articles - Poems of science: Chaucer’s doctor of physic 1 - Deadening uniformity or liberated pluralism: 5 can we learn from the past? - A tale of two teachers? 8 News Items 12 Forthcoming Events 14 Reviews - Great Physicists: the life and times of leading physicists from Galileo to Hawking 15 - Mercator: the man who mapped the planet 17 - The Lunar Men: the friends who made the future 19 - Gods in the Sky: Astronomy from the ancients to the Renaissance 21 Resources - Wright Brothers and flight 22 - Darwin and Design 22 - How to Win The Nobel Prize 22 - 1 - Editorial Martin Monk I have been helping Kate Buss with the editing for the past year. Now she has asked me to take over. I wish to thank Kate for more than four years of patience and skill in editing Education Forum. I think we all wish her well in the future. So this is the first issue of Education Forum for which I take sole responsibility Tuesday 4th May is the deadline for copy for the next issue of Education Forum. [email protected] Articles Poems of science John Cartwright In this new series John Cartwright takes a poem each issue of Forum and examines its scientific content. With last year’s BBC screening of an updated version of the Canterbury Tales there is more than one reason to start with Chaucer. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN Norman, Oklahoma 2009 SCIENCE IN THE AMERICAN STYLE, 1700 – 1800 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ________________________ Prof. Paul A. Gilje, Chair ________________________ Prof. Catherine E. Kelly ________________________ Prof. Judith S. Lewis ________________________ Prof. Joshua A. Piker ________________________ Prof. R. Richard Hamerla © Copyright by ROBYN DAVIS M CMILLIN 2009 All Rights Reserved. To my excellent and generous teacher, Paul A. Gilje. Thank you. Acknowledgements The only thing greater than the many obligations I incurred during the research and writing of this work is the pleasure that I take in acknowledging those debts. It would have been impossible for me to undertake, much less complete, this project without the support of the institutions and people who helped me along the way. Archival research is the sine qua non of history; mine was funded by numerous grants supporting work in repositories from California to Massachusetts. A Friends Fellowship from the McNeil Center for Early American Studies supported my first year of research in the Philadelphia archives and also immersed me in the intellectual ferment and camaraderie for which the Center is justly renowned. A Dissertation Fellowship from the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History provided months of support to work in the daunting Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library. The Chandis Securities Fellowship from the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens brought me to San Marino and gave me entrée to an unequaled library of primary and secondary sources, in one of the most beautiful spots on Earth. -

Augustine on Knowledge

Augustine on Knowledge Divine Illumination as an Argument Against Scepticism ANITA VAN DER BOS RMA: RELIGION & CULTURE Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Research Master Thesis s2217473, April 2017 FIRST SUPERVISOR: dr. M. Van Dijk SECOND SUPERVISOR: dr. dr. F.L. Roig Lanzillotta 1 2 Content Augustine on Knowledge ........................................................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 4 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 The life of Saint Augustine ................................................................................................................... 9 The influence of the Contra Academicos .......................................................................................... 13 Note on the quotations ........................................................................................................................ 14 1. Scepticism ........................................................................................................................................ -

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy The Renaissance was one of the most innovative periods in Western civi- lization.1 New waves of expression in fijine arts and literature bloomed in Italy and gradually spread all over Europe. A new approach with a strong philological emphasis, called “humanism” by historians, was also intro- duced to scholarship. The intellectual fecundity of the Renaissance was ensured by the intense activity of the humanists who were engaged in collecting, editing, translating and publishing the ancient literary heri- tage, mostly in Greek and Latin, which had hitherto been scarcely read or entirely unknown to the medieval world. The humanists were active not only in deciphering and interpreting these “newly recovered” texts but also in producing original writings inspired by the ideas and themes they found in the ancient sources. Through these activities, Renaissance humanist culture brought about a remarkable moment in Western intel- lectual history. The effforts and legacy of those humanists, however, have not always been appreciated in their own right by historians of philoso- phy and science.2 In particular, the impact of humanism on the evolution of natural philosophy still awaits thorough research by specialists. 1 By “Renaissance,” I refer to the period expanding roughly from the fijifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century, when the humanist movement begun in Italy was difffused in the transalpine countries. 2 Textbooks on the history of science have often minimized the role of Renaissance humanism. See Pamela H. Smith, “Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science,” Renaissance Quarterly 62 (2009), 345–75, esp. -

Christianity Unveiled; Being an Examination of the Principles and Effects of the Christian Religion

Christianity Unveiled; Being An Examination Of The Principles And Effects Of The Christian Religion by Paul Henri d’Holbach - 1761 [1819 translation by W. M. Johnson] CONTENTS. A LETTER from the Author to a Friend. CHAPTER I. - Of the necessity of an Inquiry respecting Religion, and the Obstacles which are met in pursuing this Inquiry. CHAPTER II. - Sketch of the History of the Jews. CHAPTER III. - Sketch of the History of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER IV. - Of the Christian Mythology, or the Ideas of God and his Conduct, given us by the Christian Religion. CHAPTER V. - Of Revelation. CHAPTER VI. - Of the Proofs of the Christian Religion, Miracles, Prophecies, and Martyrs. CHAPTER VII. - Of the Mysteries of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER VIII. - Mysteries and Dogmas of Christianity. CHAPTER IX. - Of the Rites and Ceremonies or Theurgy of the Christians. CHAPTER X. - Of the inspired Writings of the Christians. CHAPTER XI. - Of Christian Morality. CHAPTER XII. - Of the Christian Virtues. CHAPTER XIII. - Of the Practice and Duties of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER XIV. - Of the Political Effects of the Christian Religion. CHAPTER XV. - Of the Christian Church or Priesthood. CHAPTER XVI. - Conclusions. A LETTER FROM THE AUTHOR TO A FRIEND I RECEIVE, Sir, with gratitude, the remarks which you send me upon my work. If I am sensible to the praises you condescend to give it, I am too fond of truth to be displeased with the frankness with which you propose your objections. I find them sufficiently weighty to merit all my attention. He but ill deserves the title of philosopher, who has not the courage to hear his opinions contradicted. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

The Enlightenment, Special Ediction October 2010

The Enlightenment The Newsletter of the Humanist Association of London and Area An Affiliate of Humanist Canada (HC) Volume 6 Number 8 Special Issue Two Contrasting Legacies of the Axial Age Grecian Philosophical Rationalism & Monotheistic Christianity From about 900 to 200 BCE (Before the Common Era) in different regions of the world, four great traditions came into being that have continued to influence humanity to this day. They were Confucianism and Taoism in China; Hinduism and Buddhism in India; monotheistic Judaism in Israel (followed by its offshoot Christianity); and philosophical rationalism in Greece. This was the period of Confucius, Buddha, Jeremiah and Socrates. During this era, which came to be known as The Axial Age, spiritual and philosophical geniuses pioneered intense creativity and generated new kinds of human experiences unlike anything that had occurred up until that time. This special issue of The Enlightenment will explore the outcomes of two of these historical entities, the glory that was Greece and the monotheistic Judaism in Israel that led to the invention of Christianity and the founding of the early Roman Catholic Church. In the centuries leading up to the beginning of the Common Era (CE) great things were happening in Greece. This was the civilization that spawned philosophy, democracy, and humanism, among other things, in a polytheistic society that honoured many gods and goddesses. At the same time, not far away in Palestine, the Jews were worshiping only one God called Yahweh. In the first century CE, one of these Jews who went by the name of Jesus, organized a band of twelve disciples and began preaching a reformed gospel that irritated the leaders in the Jerusalem Temple, and possibly the Roman civic authorities as well. -

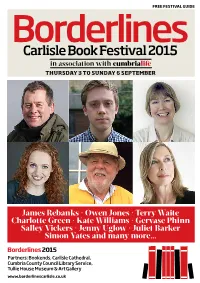

Borderlines 2015

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE BorderlinesCarlisle Book Festival 2015 in association with cumbrialife THURSDAY 3 TO SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER James Rebanks � Owen Jones � Terry Waite Charlotte Green � Kate Williams � Gervase Phinn Salley Vickers � Jenny Uglow � Juliet Barker Simon Yates and many more... Borderlines 2015 Partners: Bookends, Carlisle Cathedral, Cumbria County Council Library Service, Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery www.borderlinescarlisle.co.uk President’s welcome city strolling Rigby Phil Photography The Lanes Carlisle ell done to everyone at The growth in literary festivals in the last image courtesy of BHS Borderlines for making it decade has partly been because the such a resounding reading public, in fact the general public, success, for creating a do like to hear and see real live people for Wliterary festival and making it well and a change, instead of staring at some sort truly a part of the local community, nay, of inanimate box or computer contrap- part of national literary life. It is now so tion. The thing about Borderlines is that well established and embedded that it it is totally locally created and run, a feels as if it has been going for ever, not- for- profit event, from which no one though in fact it only began last year… gets paid. There is a committee of nine yes, only one year ago, so not much to who include representatives from boast about really, but existing- that is an Cumbria County Council, Bookends, achievement in itself. There are now Tullie House and the Cathedral. around 500 annual literary festivals in So keep up the great work. -

HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA J\Roi^RISTOWN

BULLETIN joffAe- HISTORICAL 50CIETY MONTGOMERY COUNTY PENNSYLVANIA J\rOI^RISTOWN £omery PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY AT IT5 R00M5 IS EAST PENN STREET NORRI5TOWN.PA. OCTOBER, 1939 VOLUME II NUMBER 1 PRICE 50 CENTS Historical Society of Montgomery County OFFICERS Nelson P. Fegley, Esq., President S. Cameron Corson, First Vice-President Mrs. John Faber Miller, Second Vice-President Charles Harper Smith, Third Vice-President Mrs. Rebecca W. Brecht, Recording Secretary Ella Slinglupp, Corresponding Secretary Annie B. Molony, Financial Secretary Lyman a. Kratz, Treasurer Emily K. Preston, Librarian TRUSTEES Franklin A. Stickler, Chairman Mrs. A. Conrad Jones Katharine Preston H. H. Ganser Floyd G. Frederick i David Rittenhouse THE BULLETIN of the Historical Society of Montgomery County Published Semi-Anrvmlly — October and April Volume II October, 1939 Number 1 CONTENTS Dedication of the David Rittenhouse Marker, June 3, 1939 3 David Rittenhouse, LL.D., F.R.S. A Study from ContemporarySources, Milton Rubincam 8 The Lost Planetarium of David Ritten house James K. Helms 31 The Weberville Factory Charles H. Shaw 35 The Organization of Friends Meeting at Norristown Helen E. Richards 39 Map Making and Some Maps of Mont gomery County Chester P. Cook 51 Bible Record (Continued) 57 Reports 65 Publication Committee Dr. W. H. Reed, Chairman Charles R. Barker Hannah Gerhard Chester P. Cook Bertha S. Harry Emily K. Preston, Editor 1 Dedication of the David Rittenhouse Marker June 3, 1939 The picturesque farm of Mr. Herbert T. Ballard, Sr., on Germantown Pike, east of Fairview Village, in East Norriton township, was the scene of a notable gathering, on June 3, 1939, the occasion being the dedication by the Historical So ciety of Montgomery County of the marker commemorating the observation of the transit of Venus by the astronomer, David Rittenhouse, on nearby ground, and on the same month and day, one hundred and seventy years before. -

Notes on the Almanacs of Massachusetts

1912.] Almmmcs of Massachusetts. 15 NOTES ON THE ALMANACS OF MASSACHUSETTS. BY CHARLES L. NICHOLS The origin of the almanac is wrapped in as much obscurity as that of the science of astronomy upon which its usefulness depends. It is possible, however, to trace some of the steps of its evolution and to note the uses to which it has been applied as that evolution has taken place. « When Fabius, the secretary of Appius Claudius, stole the fasti-sacri or Kalendares of the Roman priest- hood three hundred years before Christ, and exhibited the white tablets on the walls of the Forum, he not only struck a blow for reUgious freedom, but also gave to the people a long coveted source of information. Until that period no fast or holy-day had been pro- claimed except by the decision of the priests, since by their secret methods were made the calculations for those days. From that time the calendar of days has belonged to the people themselves, and has held an important position in the almanac of all nations. When Ptolemy in 150, A. D., prepared his catalogue of stars, and laid the foundation for more exact and con- tinuous records of their movements, the development of the Ephemeris, or daily note-book of the planets' places in our almanacs was assured. The meaning of the "man of signs," which is still so commonly seen, was minutely described by Manil- ius in his Astronomicon, written in the reign of the Emperor Tiberius. Origen and Jamblicus state that the principle underlying this belonged to a much earlier 16 American Aritiquarian Society. -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so.