Gregory Nazianzen's Poems on Scripture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thinking Through Matters of Faith

THINKING THROUGH MATTERS OF FAITH “Born of the Virgin Mary”: Toward a Sprachregelung on a Delicate Point of Doctrine his essay offers an interpretation of the traditional Catholic teach- Ting that “Jesus Christ, conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit, was born of the Virgin Mary.” It will be attempted to do so in such a way as to positively acknowledge three blocks of non-theological knowledge: (1) the critical difference between tacit, unspoken mean- ing-elements in speech and the invisible, unwritten meaning-elements discoverable in texts; (2) the account of the anatomical and physiolog- ical “facts” involved in human fertilization and conception as they were widely understood in the classical and medieval periods, and thus, presumably, at the place and time of the composition of the infancy narratives in the gospels of Matthew and Luke, and (3) the modern, scientific account of these same “facts,” now generally understood and accepted. Indirectly, the contrasts treated in (1) and between (2) and (3) will raise issues in the field of the hermeneutics of Christian doctrine. For all this, the author’s chief purpose in writing is systematic- theological, but in such a way as to emphasize linguistic, and hence, pastoral elements as well. After all, the accepted, shared language of faith must never be totally severed from the live speech of the people professing it, and silence is a strangely telling part of live speech. Happily, the Great Tradition’s constant teaching on this point is now being studied in many places. Unhappily, some of the scrutiny, often allegedly academic, is mixed with scorn; still, scrutinizing (as against doubting) Christian doctrine is the birthright of Christians; if they do not take advantage of this privilege, non-Christians will. -

The Homilies of John Chrysostom

366 Tsamakda Chapter 25 The Homilies of John Chrysostom Vasiliki Tsamakda The Author and His Work St John Chrysostom (c.347-407) was the most important Father of the Orthodox Church. Archbishop of Constantinople from 398 to 404, he was officially recog- nized as a Doctor of the Orthodox Church by the Council of Chalcedon in 4511 due to his vast and important theological writings.2 He was the most produc- tive among the Church Fathers, with over 1,500 works written by, or ascribed to him. His name was firmly associated with the Liturgy, but above all he was appreciated for his numerous sermons and as an extraordinary preacher. From the 6th century on he was called Chrysostomos, the “golden mouthed”. The fact that over 7,000 manuscripts including his writings exist, attests to the impor- tance and great distribution of his works, many of which were translated into other languages. The great majority of them date after the Iconoclasm. The homilies of John Chrysostom were read during the Service of the Matins (Orthros) mainly in Byzantine monasteries. They were transmitted in various collections or series from which only a few were selected for illustration. Illustrated homilies of John Chrysostom The exact number of illustrated manuscripts containing Chrysostomic ser- mons is unknown,3 but their number is extremely low in view of the very rich 1 The translation of his relics to Constantinople and their deposition in the Church of the Holy Apostles marks the beginning of his cult in Byzantium. The Orthodox Church commemorates him on 27 January, 13 November and also on 30 January together with the other two Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. -

Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa

Durham E-Theses Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Neamµu, Mihail G. How to cite: Neamµu, Mihail G. (2002) Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4187/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham Faculty of Arts Department of Theology The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Mihail G. Neamtu St John's College September 2002 M.A. in Theological Research Supervisor: Prof Andrew Louth This dissertation is the product of my own work, and the work of others has been properly acknowledged throughout. Mihail Neamtu Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa MA (Research) Thesis, September 2002 Abstract This MA thesis focuses on the work of one of the most influential and authoritative theologians of the early Church: St Gregory of Nyssa (f396). -

The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments

Durham E-Theses The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments Metallidis, George How to cite: Metallidis, George (2003) The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene : philosophical terminology and theological arguments, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1085/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM DEPARTMENT OF THEOLOGY GEORGE METALLIDIS The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consentand information derived from it should be acknowledged. The Chalcedonian Christology of St John Damascene: Philosophical Terminology and Theological Arguments PhD Thesis/FourthYear Supervisor: Prof. ANDREW LOUTH 0-I OCT2003 Durham 2003 The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene To my Mother Despoina The ChalcedonianChristology of St John Damascene CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS 7 ACKNOWLEDGMENT 12 INTRODUCTION 14 CHAPTER ONE TheLife of St John Damascene 1. -

Circumcision of the Spirit in the Soteriology of Cyril of Alexandria Jonathan Stephen Morgan Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Circumcision of the Spirit in the Soteriology of Cyril of Alexandria Jonathan Stephen Morgan Marquette University Recommended Citation Morgan, Jonathan Stephen, "Circumcision of the Spirit in the Soteriology of Cyril of Alexandria" (2013). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 277. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/277 CIRCUMCISION OF THE SPIRIT IN THE SOTERIOLOGY OF CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA by Jonathan S. Morgan, B.S., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2013 ABSTRACT CIRCUMCISION OF THE SPIRIT IN THE SOTERIOLOGY OF CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA Jonathan S. Morgan, B.S., M.A. Marquette University, 2013 In this dissertation I argue that Cyril of Alexandria’s interpretation of “spiritual circumcision” provides invaluable insight into his complex doctrine of salvation. Spiritual Circumcision – or Circumcision by the Spirit -- is a recurring theme throughout his extensive body of exegetical literature, which was written before the Nestorian controversy (428). When Cyril considers the meaning and scope of circumcision, he recognizes it as a type that can describe a range of salvific effects. For him, circumcision functions as a unifying concept that ties together various aspects of salvation such as purification, sanctification, participation, and freedom. Soteriology, however, can only be understood in relation to other doctrines. Thus, Cyril’s discussions of circumcision often include correlative areas of theology such as hamartiology and Trinitarian thought. In this way, Cyril’s discussions on circumcision convey what we are saved from, as well as the Trinitarian agency of our salvation. -

Shiatu in Arabic)—Eventually Came to Be Called Shia (Often Spelled Shiite in English Sources)

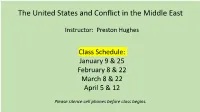

The United States and Conflict in the Middle East Instructor: Preston Hughes Class Schedule: January 9 & 25 February 8 & 22 March 8 & 22 April 5 & 12 Please silence cell phones before class begins. The US and Conflict in the Middle East Setting the Stage HITTITE EMPIRE circa 1600 BC – 1178 BC Shown in Blue is Hittite Empire circa 1300 BC The first written international treaty known to humankind, Kadesh, was made between Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II and Hittite King Hattushili, in 1269 BCE. The tablet is now displayed at the Istanbul Archeological Museum, where you can also find the oldest love poem, written by the Sumerian queen to the Sumerian king in 2037-2039 BCE. The museum also houses the Alexander Sarcophagus. Assyrian Empire circa 7th century BCE (greatest extent) Babylonia Tomb of Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenid Empire (the first Persian Empire) in the 6th century BCE The Persian Empire circa 500 BCE Empire of Alexander the Great 4th century BCE Post Alexander Armenian Empire Armenia its greatest extent under Tigranes the Great, 69 BC (including vassals) Kurds Roman Empire At its greatest extent (vassals in pink) Roman Empire Sassanid Empire The Sasanian Empire at its greatest extent c. 620 CE, under Khosrow II . Greatest temporary extent during Byzantine – Sasanian War of 602-628 shown in stripes. Next Slide: Islamic Empire For Byzantine Slide discuss who lives in Byzantine Empire, Christian heretics, conditions under which they live just prior to birth of Muhammad The Qur’an on the Qur’an We sent to you [Muhammad] the Scripture with the truth, confirming the Scriptures that came before it, and with final authority over them: so judge between them according to what God has sent down. -

Xi Colloquium Anatolicum

COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM XI 2012 INSTITUTUM TURCICUM SCIENTIAE ANTIQUITATIS TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM ANADOLU SOHBETLERİ XI 2012 INSTITUTUM TURCICUM SCIENTIAE ANTIQUITATIS TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM ANADOLU SOHBETLERİ XI ISSN 1303-8486 COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM dergisi, TÜBİTAK-ULAKBİM Sosyal Bilimler Veri Tabanında taranmaktadır. COLLOQUIUM ANATOLICUM dergisi hakemli bir dergi olup, yılda bir kez yayınlanmaktadır. © 2012 Türk Eskiçağ Bilimleri Enstitüsü Her hakkı mahfuzdur. Bu yayının hiçbir bölümü kopya edilemez. Dipnot vermeden alıntı yapılamaz ve izin alınmadan elektronik, mekanik, fotokopi vb. yollarla kopya edilip yayınlanamaz. Editörler/Editors Metin Alparslan Ali Akkaya Baskı / Printing MAS Matbaacılık A.Ş. Hamidiye Mah. Soğuksu Cad. No. 3 Kağıthane - İstanbul Tel: +90 (212) 294 10 00 Fax: +90 (212) 294 90 80 Sertifika No: 12055 Yapım ve Dağıtım/Production and Distribution Zero Prodüksiyon Kitap-Yayın-Dağıtım Ltd. Şti. Tel: +90 (212) 244 7521 Fax: +90 (212) 244 3209 [email protected] www.zerobooksonline.com TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ İstiklal Cad. No. 181 Merkez Han Kat: 2 34433 Beyoğlu-İstanbul Tel: + 90 (212) 292 0963 / + 90 (212) 514 0397 [email protected] www.turkinst.org TÜRK ESKİÇAĞ BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ Uluslararası Akademiler Birliği Muhabir Üyesi Corresponding Member of the International Union of Academies ENST‹TÜMÜZÜN KURUCUSU VE BAfiKANI PROF. DR. AL‹ D‹NÇOL’UN AZ‹Z HATIRASINA IN PERPETUAM MEMORIAM CONDITORIS PRAESIDISQUE INSTITUTI NOSTRI PROF. DR. AL‹ D‹NÇOL -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2016 Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites Katherine Rousseau University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rousseau, Katherine, "Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1129. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by T.K. Rousseau June 2016 Advisor: Scott Montgomery ©Copyright by T.K. Rousseau 2016 All Rights Reserved Author: T.K. Rousseau Title: Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites Advisor: Scott Montgomery Degree Date: June 2016 Abstract Global mediation, communication, and technology facilitate pilgrimage places with porous boundaries, and the dynamics of porousness are complex and varied. Three Marian, Catholic pilgrimage places demonstrate the potential for variation in porous boundaries: Chartres cathedral; the Marian apparition location of Medjugorje; and the House of the Virgin Mary near Ephesus. -

Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel - St

Church of Our Lady of Good Counsel - St. Thomas More OLGC - 230 East 90th Street - STM - 65 East 89th Street New York City, New York 10128 OUR LADY OF GOOD COUNSEL PARISH OFFICE (212) 289-1742 FAX (646) 669-7811 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.OLGCSTM.org ST. THOMAS MORE PARISH OFFICE (212) 876-7718 FAX (212) 831-5756 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEBSITE: www.OLGCSTM.org January 1st, 2017 SUNDAY MASS SCHEDULE - OLGC Saturday Evening: 5:30 p.m. CLERGY Sunday Morning: 9:00 a.m. Rev. Kevin V. Madigan, Pastor 10:15 a.m.- Spanish Mass Msgr. Patrick McCahill, Deaf Ministry 11:30 a.m. - Choral Mass Sunday Evening: 6:00 p.m. Rev. Fernando Caindec, Parochial Vicar Rev. Maximo Villanueva, Parochial Vicar SUNDAY MASS SCHEDULE - STM Saturday Evening: 5:45 p.m. STAFF - OLGC Sunday Morning: 8:30 a.m. 10:00 a.m. - Family Mass Email: [email protected] Sunday Afternoon: 12:00 p.m. - Choral Mass Joan Barton, Director of Music Sunday Evening: 5:45 p.m. Marcelle Devine, Coordinator of Religious Ed. Christopher Gillespie, Dir. Liturgical Music Ed. WEEKDAY MASSES - OLGC Monday thru Friday: 9:00 am and 6:00 pm STAFF - STM Saturday: 9:00 am and 12:00 pm James Siranovich, Interim Director of Music WEEKDAY MASSES - STM [email protected] Monday thru Friday: 8:00 am and 12:15 pm Edward Litcher, Business Manager Saturday: 8:00 am and 12:15 pm [email protected] CONFESSIONS - OLGC Sharon McKenna, Sacristan Monday thru Friday - 5:45 pm Alex Miller, Director of Parish Programs Saturday 4:30 – 5:15 pm [email protected] CONFESSIONS - STM Margaret Peet, Development Monday thru Friday 12:00 pm - 12:10 pm (before Mass) PARISH TRUSTEES Saturday 5:00 – 5:30 pm Christopher Baldwin BAPTISM Paul Saunders OLGC - 12:30 pm on Sunday STM - 1:00 pm on Sunday PARISH COUNCIL PRESIDENT (Arrangements must be made six weeks in advance) Alicia Damley MARRIAGE Arrangements should be made at least six months prior FINANCE COMMITTEE CHAIRPERSON to the wedding Michael Poulos VISITS TO HOMEBOUND PARISHIONERS Our clergy are happy to visit. -

The Theological and Doxological Reference to the Resurrection And

The theological and doxological reference to the Resurrection and the Pentecost according to the orations of Gregory of Nazianzus XLI and XLV La referencia teológica y doxológica a la Resurrección y al Pentecostés según las oraciones de Gregorio Nacianceno XLI y XLV La referència teològica i doxològica a la Resurrecció i la Pentecosta segons les oracions de Gregori de Nazianz XLI i XLV A referência teológica e doxológica à Ressurreição e ao Pentecostes segundo as orações de Gregório de Nazianzo XLI e XLV Eirini ARTEMI1 Abstract: In the forty-one oration, Gregory of Nazianzus analyzes the divinity of the Holy Spirit, a subject that is developed again with more severe way in his Fifth Theological Oration. Gregory tries to establish the point by quite a different set of arguments from those adopted in the former discourse, none of whose points are here repeated. In the other oration, forty-five, Gregory refers to the importance of the resurrection for the human race. He presents Christ as the new Adam who saved the human from the death and reunites again the man with God. This is a subject that is referred to the oration forty-one, too. In this paper, we will examine the teaching of Gregory of Nazianzus about the divine status of the Holy Spirit and his equality to the other two persons of the Triune God through theological and biblical images. Also, we will present how he connects his teaching for anthropology based on the Christology. In the end we will show how Gregory produced these orations for public festivals within the literarily ripe tradition of pagan festival rhetoric, but he gives to his orations theological content. -

The Alexandrian and the Cappadocian Fathers of the Church in the Writings of Thomas Aquinas

The Alexandrian and the Cappadocian Fathers of the Church in the writings of Thomas Aquinas Los Padres alejandrinos y capadocios en los escritos de Tomás de Aquino Leo J. Elders s.v.d. Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas Resumen: Santo Tomás considera que los escritos de los Padres están directamente relacionados con las Escrituras ya que fueron escritos bajo la influencia rectora del mismo Espíritu Santo. Existe, pues, una continuidad de pensamiento entre los Padres como re- presentantes de la autoridad de los Apóstoles y la Biblia. Por este motivo, sería bueno re- conocer cuán profundamente santo Tomás se inspira en el pensamiento de los Padres. En esta contribución presentaremos los temas principales dentro de los escritos de los Padres Alejandrinos y Capadocios que han influido en el propio pensamiento de santo Tomás. Palabras clave: Atanasio de Alejandría, Cirilo de Alejandría, Basilio Magno, Gre- gorio Nacianceno, Gregorio de Nisa, Tomás de Aquino. Abstract: St. Thomas considers the writings of the Fathers as directly related to Scrip- ture since these were composed under the guiding influence of the same Holy Spirit. There exists therefore a continuity of thought between the Fathers as representatives of the au- thority of the Apostles and the Bible.1 For this reason, one would do well to recognize how deeply St. Thomas draw upon the thought of the Fathers. In this contribution we will present the main themes within the writings of the Alexandrian and Cappadocian Fathers that have influenced St. Thomas’s own thought.2 Key words: Athanasius of Alexandria, Cyril of Alexandria, Basil the Great, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gregory of Nyssa, Thomas Aquinas.