Old and New John Chrysostom 15 November 2015 Peter Sarris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 2018 Newsletter

Proistamenos: Fr. Douglas Papulis ST. NICHOLAS (636) 527-7843 (314) 974-4613cell MONTHLY NEWSLETTER Parish Priest: Fr. Michael Arbanas ST. NICHOLAS GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH (314)909-6999 4967 FOREST PARK AVENUE Office (314)361-6924 ST. LOUIS, MO 63108-1495 Fax (314)361-3539 Executive Secretary: Kathy Ellis ST. NICHOLAS CHURCH FAMILY LIFE CENTER Bookkeeper: Diane Winkler 12550 S FORTY DRIVE Email: [email protected] ST. LOUIS, MO 63141 Website: www.sngoc.org January 2018 Volume 22- Number 1 The Feast of Epiphany Christ, according to Orthodox teaching, gave the rite of passage to the Church on the day He Himself was baptized. On this day, St. Gregory of Nyssa tells us, Jesus entered the filthy water of the world, and thereafter brought up and purified the world. It is this purification through Je- sus’ Baptism that we commemorate on this day. And it is God’s revelation of Himself as Trinity who makes salvation and eternal life possible, that we also observe. Epiphany’s Gospel les- son, which comes from Matthew 3:12-17, speaks to us about these events, both of which are necessary for salvation The Gospel lesson is a simple one. Shortly before Jesus’ desert experience and the com- mencement of his earthly ministry, Jesus went to the River Jordan to be Baptized by his cousin John. John, on seeing Jesus, knowing that He is without sin, sought to prevent Him from being baptized by saying, “I need to be Baptized by you, and are you coming to me” (Jn. 3:14)? But Jesus retorted by saying, “Permit it to be so now, for thus it is fitting to fulfill all righteousness.” Oh what a marvel! Jesus who was fully God and fully man, who had no need to be saved “through the washing of regeneration and renewing of the Holy Spirit,” condescended to be Baptized. -

The Homilies of John Chrysostom

366 Tsamakda Chapter 25 The Homilies of John Chrysostom Vasiliki Tsamakda The Author and His Work St John Chrysostom (c.347-407) was the most important Father of the Orthodox Church. Archbishop of Constantinople from 398 to 404, he was officially recog- nized as a Doctor of the Orthodox Church by the Council of Chalcedon in 4511 due to his vast and important theological writings.2 He was the most produc- tive among the Church Fathers, with over 1,500 works written by, or ascribed to him. His name was firmly associated with the Liturgy, but above all he was appreciated for his numerous sermons and as an extraordinary preacher. From the 6th century on he was called Chrysostomos, the “golden mouthed”. The fact that over 7,000 manuscripts including his writings exist, attests to the impor- tance and great distribution of his works, many of which were translated into other languages. The great majority of them date after the Iconoclasm. The homilies of John Chrysostom were read during the Service of the Matins (Orthros) mainly in Byzantine monasteries. They were transmitted in various collections or series from which only a few were selected for illustration. Illustrated homilies of John Chrysostom The exact number of illustrated manuscripts containing Chrysostomic ser- mons is unknown,3 but their number is extremely low in view of the very rich 1 The translation of his relics to Constantinople and their deposition in the Church of the Holy Apostles marks the beginning of his cult in Byzantium. The Orthodox Church commemorates him on 27 January, 13 November and also on 30 January together with the other two Cappadocian Fathers, Basil the Great and Gregory of Nazianzus. -

Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa

Durham E-Theses Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Neamµu, Mihail G. How to cite: Neamµu, Mihail G. (2002) Language and theology in St Gregory of Nyssa, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4187/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk University of Durham Faculty of Arts Department of Theology The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa Mihail G. Neamtu St John's College September 2002 M.A. in Theological Research Supervisor: Prof Andrew Louth This dissertation is the product of my own work, and the work of others has been properly acknowledged throughout. Mihail Neamtu Language and Theology in St Gregory of Nyssa MA (Research) Thesis, September 2002 Abstract This MA thesis focuses on the work of one of the most influential and authoritative theologians of the early Church: St Gregory of Nyssa (f396). -

The Forerunner

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

BC Times Spring 2012 (Pdf)

2625 West Ninth Street, SPRING 2012 Bernardine Center Staff Chester, PA 19013 P: 610.497.3225 Sister Carolyn Muus F: 610.497.3659 Hunger Facts Coordinator of Westside Brunch [email protected] Sister plans the menus, www.bernardinecenter.org • More than one in seven Americans – prepares and oversees the including more than one in five children – serving of healthy brunch A NEWSLETTER OF THE BERNARDINE CENTER meals three times each THE live below the poverty line week for hungry folks in ($22,113 for a family of four). the neighborhood. Sister Sister Maria Denise Prorock also works alongside Food Pantry Assistant • The number of people at risk of hunger volunteers who offer Organizes and distributes Center in the United States increased from 36.2 to prepare and serve supplies and donated clothing Bernardine million in 2007 to 48.8 million in 2010. occasional brunch meals. to families and individuals who seek assistance from our center. Sister develops the diverse • Food banks in the United States saw a Mary Lou Laboy monthly thank you letters that 46 percent increase in clients seeking Food Pantry Coordinator receive so many compliments emergency food assistance between 2006 Orders food, organizes from our donors. and 2010. food shelves and plans Bernardine Center is grateful to Danny Califf (Philadelphia Union Defender) and his for the distribution ETHEL SARGEANT CLARK SMITH wife Erin with their children took the opportunity to learn of emergency and • One in seven Americans currently receive supplemental food; Sister Sandra Lyons MEMORIAL FUND SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance about hunger and served Westside Brunch during the Christmas holidays. -

Church Newsletter

Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos Missionary Parish, Orange County, California CHURCH NEWSLETTER January – March 2010 Parish Center Location: 2148 Michelson Drive (Irvine Corporate Park), Irvine, CA 92612 Fr. Blasko Paraklis, Parish Priest, (949) 830-5480 Zika Tatalovic, Parish Board President, (714) 225-4409 Bishop of Nis Irinej elected as new Patriarch of Serbia In the early morning hours on January 22, 2010, His Eminence Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, locum tenens of the Patriarchate throne, served the Holy Hierarchal liturgy at the Cathedral church. His Eminence served with the concelebration of Bishops: Lukijan of Osijek Polje and Baranja, Jovan of Shumadia, Irinej of Australia and New Zealand, Vicar Bishop of Teodosije of Lipljan and Antonije of Moravica. After the Holy Liturgy Bishops gathered at the Patriarchate court. The session was preceded by consultations before the election procedure. At the Election assembly Bishop Lavrentije of Shabac presided, the oldest bishop in the ordination of the Serbian Orthodox Church. The Holy Assembly of Bishops has 44 members, and 34 bishops met the requirements to be nominated as the new Patriarch of Serbia. By the secret ballot bishops proposed candidates, out of which three bishops were on the shortlist, who received more than half of the votes of the members of the Election assembly. In the first round the candidate for Patriarch became the Metropolitan Amfilohije of Montenegro and the Littoral, in the second round the Bishop Irinej of Nis, and a third candidate was elected in the fourth round, and that was Bishop Irinej of Bachka. These three candidates have received more that a half votes during the four rounds of voting. -

'Incident at Antioch': Chrysostom on Galatians 2:11-14

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Apostolic authority and the ‘incident at Antioch’: Chrysostom on Galatians 2:11-14 Griffith, Susan B License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NoDerivs (CC BY-ND) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Griffith, SB 2017, Apostolic authority and the ‘incident at Antioch’: Chrysostom on Galatians 2:11-14. in Studia Patristica: Papers presented at the Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic Studies held in Oxford 2015. vol. 96, Studia Patristica, vol. 96, Peeters, Leuven, Belgium, pp. 117-126, Seventeenth International Conference on Patristic Studies, Oxford, United Kingdom, 10/08/15. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Open access fees paid by COMPAUL project in 2016. General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Circumcision of the Spirit in the Soteriology of Cyril of Alexandria Jonathan Stephen Morgan Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Circumcision of the Spirit in the Soteriology of Cyril of Alexandria Jonathan Stephen Morgan Marquette University Recommended Citation Morgan, Jonathan Stephen, "Circumcision of the Spirit in the Soteriology of Cyril of Alexandria" (2013). Dissertations (2009 -). Paper 277. http://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/277 CIRCUMCISION OF THE SPIRIT IN THE SOTERIOLOGY OF CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA by Jonathan S. Morgan, B.S., M.A. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2013 ABSTRACT CIRCUMCISION OF THE SPIRIT IN THE SOTERIOLOGY OF CYRIL OF ALEXANDRIA Jonathan S. Morgan, B.S., M.A. Marquette University, 2013 In this dissertation I argue that Cyril of Alexandria’s interpretation of “spiritual circumcision” provides invaluable insight into his complex doctrine of salvation. Spiritual Circumcision – or Circumcision by the Spirit -- is a recurring theme throughout his extensive body of exegetical literature, which was written before the Nestorian controversy (428). When Cyril considers the meaning and scope of circumcision, he recognizes it as a type that can describe a range of salvific effects. For him, circumcision functions as a unifying concept that ties together various aspects of salvation such as purification, sanctification, participation, and freedom. Soteriology, however, can only be understood in relation to other doctrines. Thus, Cyril’s discussions of circumcision often include correlative areas of theology such as hamartiology and Trinitarian thought. In this way, Cyril’s discussions on circumcision convey what we are saved from, as well as the Trinitarian agency of our salvation. -

An Analysis of the Rhetoric of St. John Chrysostom with Special Reference to Selected Homilies on the Gospel According to St

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1949 An Analysis of the Rhetoric of St. John Chrysostom with Special Reference to Selected Homilies on the Gospel According to St. Matthew Henry A. Toczydlowski Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Toczydlowski, Henry A., "An Analysis of the Rhetoric of St. John Chrysostom with Special Reference to Selected Homilies on the Gospel According to St. Matthew" (1949). Master's Theses. 702. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/702 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1949 Henry A. Toczydlowski AN AN!LYSIS OF THE RHETORIC OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOK WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO SELECTED HOMILIES ON mE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. MATTHEW' by Henry A. Toozydlowski A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ1r~ents tor the Degree of Master of Arts in Loyola University June 1949 LIFE Henry A. Toczydlowski was born in Chicago, Illinois, October 20, Be was graduated trom Quigley Preparatory Saainary, Chicago, Illinois, June, 1935, and trom St. Mary ot the Lake Seminary, Mundelein, Ill1Doil, June, 1941, with the degree ot Master ot Arts, and ot Licentiate .t Sacred Theology. He waa ordained priest by Hia Eminenoe Saauel Cardinal &tritoh, Kay 3, 1941. -

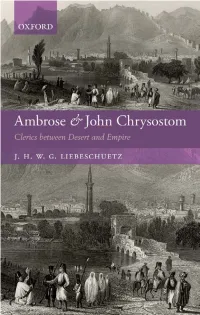

AMBROSE and JOHN CHRYSOSTOM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Ambrose and John Chrysostom Clerics Between Desert and Empire

AMBROSE AND JOHN CHRYSOSTOM This page intentionally left blank Ambrose and John Chrysostom Clerics between Desert and Empire J. H. W. G. LIEBESCHUETZ 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With oYces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # J. H. W. G. Liebeschuetz 2011 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other -

The Figure of Joseph the Patriarch in the New Testament and the Early Church

ABSTRACT “Much More Ours Than Yours”: The Figure of Joseph the Patriarch in the New Testament and the Early Church by John Lee Fortner This paper investigates the figure of Joseph the patriarch in early Christian interpretation, demonstrating the importance of such figures in articulating a Christian reading of the history of Israel, and the importance of this reading in the identity formation of early Christianity. The paper also illumines the debt of this Christian reading of Israel’s history to the work of Hellenistic Judaism. The figure of Joseph the patriarch is traced through early Christian interpretation, primarily from the Eastern Church tradition up to the 4th century C.E. The key methodological approach is an analysis of how the early church employed typological, allegorical, and moral exegesis in its construction of Joseph as a “Christian saint of the Old Testament.” A figure who, to borrow Justin Martyr’s phrase, became in the Christian identity “much more ours than yours.” “Much More Ours Than Yours”: The Figure of Joseph the Patriarch in the New Testament and the Early Church A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by John Lee Fortner Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2004 Advisor ________________________ Dr. Edwin Yamauchi Reader ________________________ Dr. Charlotte Goldy Reader _________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Table of Contents Introduction 1 Early Christian Hermeneutics 1 The Aura of Antiquity 6 Apologetics of Hellenistic Judaism 8 Scope and Purpose of Study 12 1. Joseph in the New Testament 13 Acts 7 14 Heb 11 15 2. -

The Patristic Witness to the Virgin Mary As the New Eve

Marian Studies Volume 29 Proceedings of the Twenty-ninth National Convention of The Mariological Society of America Article 9 held in Baltimore, Md. 1978 The aP tristic Witness to the Virgin Mary as the New Eve J. A. Ross Mackenzie Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Ross Mackenzie, J. A. (1978) "The aP tristic Witness to the Virgin Mary as the New Eve," Marian Studies: Vol. 29, Article 9. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol29/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Ross Mackenzie: The Patristic Witness to the New Eve THE PATRISTIC WITNESS TO THE VIRGIN MARY AS THE NEW EVE A Retttrn to the Historical Witness The angel who brought the news of Jesus' birth to Mary uses words, recorded by St. Luke, which were hallowed within Jewish tradition. The account is given with a reserve, a purity of expression, and a lyrical form that undoubtedly arose and took shape in the liturgical life of the early Church. Six hundred years after St. Luke composed his Gospel,Germanus, patriarch of Constantinople and devoted supporter of the cult of Mary in that place, acclaimed her thus in a sermon on the Dormition of the Virgin: Indeed, you are the Mother of true life, the leaven of Adam's recreation, Eve's freedom from reproach.