The Routledge International Handbook of Sexual Addiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Outer Circle the Official Newsletter of The

The Outer Circle The Official Newsletter of the PO Box 70949, Houston, TX 77270 Volume 3, Issue 4 July - August 2009 ® THE ISO ENCOURAGES GROUPS TO REPRODUCE THE OUTER CIRCLE SO THAT COPIES WILL BE AVAILABLE I TO ALL MEMBERS. THE OUTER CIRCLE IS MAILED FREE TO ALL WHO REQUEST IT. VOLUME 3, ISSUE 4 Table of Contents PAGE 1 ISO News Articles ISO Financial News ISO Board News Income/Expense Summary Page 14 ISO Board Actions Page 2 Financial Results Letter Page 15 Delegate Actions Page 5 Letter from the Editor Literature Committee News By M ke L. Page 16 Report From Oakland Page 6 Personal Story General ISO Information Submission Guidelines Page 9 E-mail Addresses Page 38 Opinion Poll / Survey Page 10 ISO Structure & Contacts Page 39 Feedback on Article Submissions Sex Addicts Anonymous Page 11 Guidelines, Deadlines, and Meditation Book Submission Guidelines Page 12 Topic Suggestions Page 40 Release Form Page 40 Literature Articles Stepping Up to Service in Oakland Page 19 Going to a Convention Page 22 Remembrance Page 23 Step Five Page 26 My Story Page 28 In Solitude is the Solution Page 31 A Recovery Choice: Dishonesty or Honesty Page 32 Sharing My Second Step Page 34 © Copyright 2009 International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Except for the purpose of redistributing The Outer Circle as a whole, The Outer Circle may not be downloaded, copied, reproduced, duplicated, or conveyed in any other way without the express written permission of Interna- tional Service Organization of SAA, Inc. ® Registered Trademark Sex Addicts Anonymous and the SAA logo are registered trademarks of the International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. -

Are Your Sexual Behaviors Causing You Problems.Web2.Indd

Are Your Sexual Behaviors Causing You Problems? Literature Committee Approved March 2021 PI/CPC Series © 2021 International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. • Do you keep secrets about or hide your behaviors? • Have your behaviors damaged important relationships? • Has your avoidance of sex or intimacy damaged important relationships? • Do you try to stop certain behaviors only to repeat them over and over again? • Does your sexual behavior lack loving connection with self or others? You are not alone – Sex Addicts Anonymous can help Sex Addicts Anonymous is a fellowship whose members share their experience, strength, and hope with each other so that they may fi nd freedom from addictive sexual be- havior and help others recover from sexual addiction. SAA was founded in 1977 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Today SAA is an international fellowship with meetings in many countries. Is sex addiction real? This is a common question. We can defi nitely say that for us, sex addiction exists. It’s true that not every person who has an affair, watches pornography, or uses a dating app is a sex addict. We have found most sex addicts experience one or both of these characteristics: once we start we can- not control our behaviors, or when we make up our mind to quit, sooner or later we return to those behaviors. We have also found that sex addiction is progressive, with the behaviors and their consequences usually becoming more severe over time. Examples of addictive sexual behavior • Porn addiction, cyber stalking or sex • Compulsive sexting, using social -

SEX ADDICTION and DIVORCE Cynthia L

SEX ADDICTION AND DIVORCE Cynthia L. Ciancio, Esq., and David A. Lamb, Esq. August 2015 – Family Law Institute 1. Sex Addiction, What is it? Is it Even Real? While there still does not appear to be an official diagnoses of “sex addiction,” it certainly is real, and it is a growing prevalent problem in society. As divorce practitioners, we are experiencing more and more cases driven by an underlying sex addiction by one or both spouses. The degree and severity of the addiction vary widely from case to case. The DSM-IV and V refer to sex addiction as “Hypersexuality” and/or “Sexual Disorders Not Otherwise Specified.” Web MD uses the term “hypersexual disorder (HD).” Other experts have referred to it simply as an “addiction disorder” or a “behavior disorder,” and others refer to sex addiction as being associated with “obsessive compulsive disorder.” One treatment oriented website, The Recovery Ranch, had a concise definition followed by a criteria list as follows1: DSM 5 PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR HYPERSEXUAL DISORDER Over a period of at least 6 months, recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual urges, or sexual behaviors in association with 3 or more of the following 5 criteria: 1 Should Sexual Addiction Be In the DSM-V, http://www.recoveryranch.com/articles/sexual-addiction-hypersexuality-dsm-v/ 1 1. Time consumed by sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors repetitively interferes with other important (non-sexual) goals, activities and obligations. 2. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors in response to dysphoric mood states (e.g., anxiety, depression, boredom, irritability). 3. -

Mixed Methods Analysis of Counselor Views, Attitudes and Perceived Competencies Regarding the Treatment of Internet Pornography Addiction

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2013 Mixed Methods Analysis of Counselor Views, Attitudes and Perceived Competencies Regarding the Treatment of Internet Pornography Addiction Bradly K. Hinman Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hinman, Bradly K., "Mixed Methods Analysis of Counselor Views, Attitudes and Perceived Competencies Regarding the Treatment of Internet Pornography Addiction" (2013). Dissertations. 207. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/207 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIXED METHODS ANALYSIS OF COUNSELOR VIEWS, ATTITUDES AND PERCEIVED COMPETENCIES REGARDING THE TREATMENT OF INTERNET PORNOGRAPHY ADDICTION by Bradly K. Hinman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Counselor Education and Counseling Psychology Western Michigan University December 2013 Doctoral Committee: Gary H. Bischof, Ph.D., Chair Alan Hovestadt, Ed.D. Karen Blaisure, Ph.D. MIXED METHODS ANALYSIS OF COUNSELOR VIEWS, ATTITUDES AND PERCEIVED COMPETENCIES REGARDING THE TREATMENT OF INTERNET PORNOGRAPHY -

Welcome to the IRI 7-‐Step Training for Therapists

Welcome to the IRI 7-Step Training For Therapists Version: 3.0 Date: May 2015 Course Tools: http://infidelityrecoveryinstitute.com/7-step-infidelity-recovery- program-proFessional-training/ © Copyright 2015 by The Infidelity Recovery Institute, all rights reserved 2 Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 The 7-Step InFidelity Recovery Model ................................................................................................................................... 6 The 7 Types oF AFFairs ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 What Is The Infidelity Recovery Model? ......................................................................................... 7 General InFormation: ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 General Purpose: ............................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Terms .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Goals of training ........................................................................................................................................ -

Bound to Shame: Sexual Addiction and Christian Ethics

Durham E-Theses Bound to Shame: Sexual Addiction and Christian Ethics ARENS, JOHANNES How to cite: ARENS, JOHANNES (2011) Bound to Shame: Sexual Addiction and Christian Ethics , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/714/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Johannes Arens Bound to Shame: Sexual Addiction and Christian Ethics Abstract This thesis is an attempt to add understanding and meaning to the concept of sexual addiction by correlating the clinical observation that sex addicts in particular, and shame-bound people in general, behave in cycles of control and release to the types of the two sons in the Lukan parable of the prodigal. This parable may be understood as shedding light on the equal dangers of patterns of control and release. Additionally, sex addiction is viewed from an Augustinian perspective of sin. -

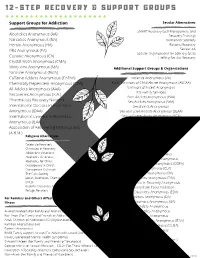

12-Step Recovery Groups

1 2 - S T E P R E C O V E R Y & S U P P O R T G R O U P S Support Groups for Addiction Secular Alternatives SMART Recovery (Self-Management and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) Recovery Training) Narcotics Anonymous (NA) Women for Sobriety Heroin Anonymous (HA) Rational Recovery Pills Anonymous (PA) Secular AA Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS) Cocaine Anonymous (CA) LifeRing Secular Recovery Crystal Meth Anonymous (CMA) Marijuana Anonymous (MA) Additional Support Groups & Organizations Nicotine Anonymous (NicA) Caffeine Addicts Anonymous (CAFAA) Violence Anonymous (VA) Chemically Dependent Anonymous (CDA) Adult Survivors of Child Abuse Anonymous (ASCAA) All Addicts Anonymous (AAA) Survivors of Incest Anonymous lDS Family Services Recoveries Anonymous (R.A.) Porn Addicts Anonymous (PAA) Pharmacists Recovery Network Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) International Doctors in Alcoholics Sexaholics Anonymous Anonymous (IDAA) Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA) International Lawyers in Alcoholics Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA) Anonymous (ILAA) Sexual Recovery ANonymous (SRA) Association of Recovering Motorcyclists Co-dependents Anonymous (CoDa) Emotions Anonymous (A.R.M.) Religious Alternatives Dual Recovery Anonymous Depressed Anonymous Celebrate Recovery Social Anxiety Anonymous Christians in Recovery PTSD Anonymous Addictions Victorious Self Mutilators Anonymous Alcoholics Victorious Obsessive Compulsive Anonymous Alcoholics for Christ Obsessive Skin Pickers Anonymous (OSPA) Overcomers in Christ Overcomers Outreach Clutters Anonymous (CLA) -

The Pornography Pandemic: Implications, Scope and Solutions for the Church in the Post-Internet Age

Southeastern University FireScholars Selected Honors Theses Spring 2018 THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE Dillon A. Diaz Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Diaz, Dillon A., "THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE" (2018). Selected Honors Theses. 127. https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors/127 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE by Dillon Amadeus Diaz Submitted to the Honors Program Committee in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors Scholars Southeastern University 2018 Diaz 1 Copyright by Dillon Amadeus Diaz 2018 Diaz 2 Dedication To Dr. Gordon Miller, whose Thesis class I accidentally missed on the 12th of March, 2018. I asked if I missed anything important; he replied, “Of course you missed something important. My class is always important.” To Dr. Joseph Davis, my thesis advisor and greatest inspiration in the defense of the true faith, whose words still ring true in my ears: “You either worship a God of revelation, or a God of imagination.” To Abigail Sprinkle, my beautiful bride-to-be, lovely beyond compare. One night, I told her every wicked thing I had ever done, and she looked at me with a smile that betrayed everything I had just confessed. -

The Outer Circle

The Outer Circle The Newsletter of the International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. PO Box 70949, Houston, TX 77270 Volume 7, Issue 6 November - December 2013 ® THE ISO ENCOURAGES GROUPS TO REPRODUCE THE ISOTHE ENCOURAGES OUTER CIRCLE, GROUPS SO THAT COPIESTO REPRODUCE WILL BE THE AVAILABLE TO ALL MEMBERS. PLAIN BROWN RAPPER SO THAT COPIES WILL BE AVAILABLETHE OUTERTO ALL CIRCLE MEMBERS. IS VIEWABLE THE OUTERONLINE AT:CIRCLE IS MAILED FREEwww.saa-recovery.org/Newsletter/ TO ALL WHO REQUEST IT. THE OUTER CIRCLE IS MAILED FOR FREE UPON REQUEST. MEMBER DONATIONS ARE GRATEFULLY ACCEPTED. VOLUME 7, ISSUE 6 Table of Contents PAGE 31 ISO News ISO News & Announcements Literature Committee News Board Actions Page 2 Meditation Book Submission Guidelines Page 10 Conference Charter News Page 2 Tele-Workshops Page 11 ISO Structure Personal Story Submissions Committee News Page 4 and Guidelines Page 12 Please Write a Mediation Page 5 ISO Financial News ISO to Hire New Editor Income/Expense Summary Page 14 for The Outer Circle Page 6 Financial Results Letter Page 15 LGBT Outreach Subcommittee News Page 7 Additional Information Women’s Outreach ISO E-mail Addresses Page 34 Subcommittee News Page 8 ISO Structure & Contacts Page 35 Article Guidelines, Deadlines, Topics, and Release Form Page 36 Member Articles From the Editor Page 16 Step Twelve, Tradition Twelve, and Right Thinking Page 18 Give ’Til It Feels Good! Page 19 Dear Grace Page 20 Dear Will Page 22 Every Day New Page 23 A Christmas Surprise in My Outer Circle Page 24 Signing Up for Sobriety? It’s Like Signing Up for a Marathon Page 25 Relationships and Tradition Three Page 26 I Was Standing at the Fork Page 28 A Way Out of the Shame and the Despair Page 29 Letting Go of Ego Page 32 © Copyright 2013 International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. -

Sex in the Sanctuary: Art, Faith and Female Sexual Addiction

Merrimack College Merrimack ScholarWorks Community Engagement Student Work Education Student Work Spring 2020 Sex in the Sanctuary: Art, Faith and Female Sexual Addiction Katrina Everett Merrimack College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/soe_student_ce Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Everett, Katrina, "Sex in the Sanctuary: Art, Faith and Female Sexual Addiction" (2020). Community Engagement Student Work. 39. https://scholarworks.merrimack.edu/soe_student_ce/39 This Capstone - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Education Student Work at Merrimack ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Engagement Student Work by an authorized administrator of Merrimack ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: ART, FAITH AND FEMALE SEXUAL ADDICTION 1 Sex in the Sanctuary: Art, Faith and Female Sexual Addiction Katrina Everett Merrimack College 2020 ART, FAITH AND FEMALE SEXUAL ADDICTION 2 MERRIMACK COLLEGE CAPSTONE PAPER SIGNATURE PAGE CAPSTONE SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF EDUCATION IN COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT CAPSTONE TITLE: Sex in the Sanctuary: Art, Faith and Female Sexual Addiction AUTHOR: Katrina Everett THE CAPSTONE PAPER HAS BEEN ACCEPTED BY THE COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF EDUCATION IN COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT. Audrey Falk, Ed.D. May 2, 2020 DIRECTOR, COMMUNITY SIGNATURE DATE ENGAGEMENT Melissa Nemon, Ph.D. May 2, 2020 INSTRUCTOR, CAPSTONE SIGNATURE DATE COURSE ART, FAITH AND FEMALE SEXUAL ADDICTION 3 Acknowledgments To my husband who has been abundantly supportive during this past year, I could not have accomplished this work without you. -

Male Sexual Addiction

NATIONAL FORUM JOURNAL OF COUNSELING AND ADDICTION VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1, 2012 Male Sexual Addiction LaVelle Hendricks, EdD Assistant Professor Department of Psychology, Counseling, and Special Education College of Education and Human Services Texas A&M University-Commerce Commerce, TX ______________________________________________________________________________ Abstract For years the question of whether sexual addiction can be considered an actual “addiction” has been the focus of many discussions among psychological practitioners. Licensed Marriage & Family Therapist, Sharon O’Hara states that in order for a behavior to be considered an addiction it must be certain elements present such as: unable to stop the behavior despite negative consequences, presence of a mood-altered state, strong element of denial, behavior is chronic and escalating because of tolerance, and occurrence of withdrawal symptoms (2004). Despite many people claiming to be addicted to sex, an actual diagnosis has been slow to come. However, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) is currently working on including sexual addiction as an actual disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). ______________________________________________________________________________ More frequently related to men than to women, sexual addiction exhibits some of the same signs and symptoms as other addictions, such as those with drug and alcohol. And just as with drug and alcohol addiction, treatment is available. Sexual addiction is the term used to describe a person’s overwhelming desire to have sex. Other names used for sexual addiction include: hypersexuality, erotomania, perversion, and sexual obsession. It is important to make clear the difference between simply enjoying sex and having an unusual intense sex drive or obsession with sex. -

Addictive Sexual Disorders

Addictive Sexual Disorders Richard R. Irons, MD 0 Jennifer PgSchneider, MD,PhD Indulgence in the gratification of sexual de‑ gage in fantasy and seductive behavior with sires and appetites to excess has been a major out significant consequences to their persona subject in literature, myths, and the creative or professional life. However, for some, it i: arts from the begirming of recorded history. notpossible to limitthe intensity of their desire One example of the hyp'ersexual predatory or expression of sexual behavior. For them male is DonJuan, the legendary lover of many sexual excesses can become addictive in nature women, who suffered a multitude of adverse and represent a serious mental disorder. consequences, including death, as a result of A distinction mustbe madebetween a situa‑ his behavior. He is immortalized asthe sexual tional and a pervasive use of sex. Twc athlete who worshipped the female body as surveys" 2 confirm that unmarried persons the ideal object of desire, created for himto be have more sexual partners than married peo consumed and ravished, and who had to make ple. For most,sexual variety is situational. Oth‑ his escape from each one before potential en‑ ers, dealing with a life crisis such as the gulfrnent by intimacy in a relationship. His breakup of a relationship, may find themselves story was immortalized in the plays of Cor‑ using sex compulsively for a brief period. For neille, Moliere, Shaw, and Rostand, in Byron’s those with addictive sexual disorders, on the unfinished poem, and in Mozart’s Don Gio‑ other hand, sex is the pervasive organizing vanni.