Bound to Shame: Sexual Addiction and Christian Ethics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Outer Circle the Official Newsletter of The

The Outer Circle The Official Newsletter of the PO Box 70949, Houston, TX 77270 Volume 3, Issue 4 July - August 2009 ® THE ISO ENCOURAGES GROUPS TO REPRODUCE THE OUTER CIRCLE SO THAT COPIES WILL BE AVAILABLE I TO ALL MEMBERS. THE OUTER CIRCLE IS MAILED FREE TO ALL WHO REQUEST IT. VOLUME 3, ISSUE 4 Table of Contents PAGE 1 ISO News Articles ISO Financial News ISO Board News Income/Expense Summary Page 14 ISO Board Actions Page 2 Financial Results Letter Page 15 Delegate Actions Page 5 Letter from the Editor Literature Committee News By M ke L. Page 16 Report From Oakland Page 6 Personal Story General ISO Information Submission Guidelines Page 9 E-mail Addresses Page 38 Opinion Poll / Survey Page 10 ISO Structure & Contacts Page 39 Feedback on Article Submissions Sex Addicts Anonymous Page 11 Guidelines, Deadlines, and Meditation Book Submission Guidelines Page 12 Topic Suggestions Page 40 Release Form Page 40 Literature Articles Stepping Up to Service in Oakland Page 19 Going to a Convention Page 22 Remembrance Page 23 Step Five Page 26 My Story Page 28 In Solitude is the Solution Page 31 A Recovery Choice: Dishonesty or Honesty Page 32 Sharing My Second Step Page 34 © Copyright 2009 International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Except for the purpose of redistributing The Outer Circle as a whole, The Outer Circle may not be downloaded, copied, reproduced, duplicated, or conveyed in any other way without the express written permission of Interna- tional Service Organization of SAA, Inc. ® Registered Trademark Sex Addicts Anonymous and the SAA logo are registered trademarks of the International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. -

Are Your Sexual Behaviors Causing You Problems.Web2.Indd

Are Your Sexual Behaviors Causing You Problems? Literature Committee Approved March 2021 PI/CPC Series © 2021 International Service Organization of SAA, Inc. • Do you keep secrets about or hide your behaviors? • Have your behaviors damaged important relationships? • Has your avoidance of sex or intimacy damaged important relationships? • Do you try to stop certain behaviors only to repeat them over and over again? • Does your sexual behavior lack loving connection with self or others? You are not alone – Sex Addicts Anonymous can help Sex Addicts Anonymous is a fellowship whose members share their experience, strength, and hope with each other so that they may fi nd freedom from addictive sexual be- havior and help others recover from sexual addiction. SAA was founded in 1977 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Today SAA is an international fellowship with meetings in many countries. Is sex addiction real? This is a common question. We can defi nitely say that for us, sex addiction exists. It’s true that not every person who has an affair, watches pornography, or uses a dating app is a sex addict. We have found most sex addicts experience one or both of these characteristics: once we start we can- not control our behaviors, or when we make up our mind to quit, sooner or later we return to those behaviors. We have also found that sex addiction is progressive, with the behaviors and their consequences usually becoming more severe over time. Examples of addictive sexual behavior • Porn addiction, cyber stalking or sex • Compulsive sexting, using social -

Igrati Sa Sobom Bili Ajdol.Indd

Preveo Dejan Cukić Naslov originala Billy Idol Dancing with Myself Copyright © 2014 by Billy Idol Translation copyright © 2015 za srpsko izdanje, LAGUNA Za Džoun i Bila Brouda SADRŽAJ PROLOG: Kažu da, ako čuješ tresak, još uvek si živ 1 PRVI DEO: LONDON Prvo poglavlje: Prvi buntovnički krik 11 Drugo poglavlje: Razigrani London 21 Treće poglavlje: Rokenrol gimnazija – duga kosa, zvoncare i cigarete sa hašišom 38 Četvrto poglavlje: Dudlanje sedamdesetih 53 Peto poglavlje: I bî pank 67 Šesto poglavlje: U revoluciji, jedna godina je kao pet 74 Sedmo poglavlje: Generation X zauzima pozicije – Vilijam Broud postaje Bili Ajdol 80 Osmo poglavlje: Noć u Roksiju 93 Deveto poglavlje: Odrastanje panka u „sudaru dve sedmice“ 104 Deseto poglavlje: „Mladost, mladost, mladost“ – proboj na drugu stranu 113 viii Bili Ajdol Jedanaesto poglavlje: Belo svetlo, Belo usijanje, Bela pobuna 117 Dvanaesto poglavlje: Ne rasprodaja, već ulog 121 Trinaesto poglavlje: Veze preko okeana 134 Četrnaesto poglavlje: Spremi se, pozor, kreni 142 Petnaesto poglavlje: Pretpostavljam da jednostavno ne znam 159 Šesnaesto poglavlje: Bolje u se i u svoje kljuse 164 DRUGI DEO: NJUJORK Sedamnaesto poglavlje: Rokenrol konkistador osvaja Ameriku pa spaljuje sopstvene brodove 177 Osamnaesto poglavlje: Nastajanje „Mony Mony“ – spoj panka i diska sa Zapadne obale 186 Devetnaesto poglavlje: Ako ovde uspeš 195 Dvadeseto poglavlje: „Vrelina u gradu“ – nastanak soliste Bilija Ajdola 201 Dvadeset prvo poglavlje: Holivudska omama i noći tekile 210 Dvadeset drugo poglavlje: Hoću svoj MTV – -

SEX ADDICTION and DIVORCE Cynthia L

SEX ADDICTION AND DIVORCE Cynthia L. Ciancio, Esq., and David A. Lamb, Esq. August 2015 – Family Law Institute 1. Sex Addiction, What is it? Is it Even Real? While there still does not appear to be an official diagnoses of “sex addiction,” it certainly is real, and it is a growing prevalent problem in society. As divorce practitioners, we are experiencing more and more cases driven by an underlying sex addiction by one or both spouses. The degree and severity of the addiction vary widely from case to case. The DSM-IV and V refer to sex addiction as “Hypersexuality” and/or “Sexual Disorders Not Otherwise Specified.” Web MD uses the term “hypersexual disorder (HD).” Other experts have referred to it simply as an “addiction disorder” or a “behavior disorder,” and others refer to sex addiction as being associated with “obsessive compulsive disorder.” One treatment oriented website, The Recovery Ranch, had a concise definition followed by a criteria list as follows1: DSM 5 PROPOSED DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR HYPERSEXUAL DISORDER Over a period of at least 6 months, recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual urges, or sexual behaviors in association with 3 or more of the following 5 criteria: 1 Should Sexual Addiction Be In the DSM-V, http://www.recoveryranch.com/articles/sexual-addiction-hypersexuality-dsm-v/ 1 1. Time consumed by sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors repetitively interferes with other important (non-sexual) goals, activities and obligations. 2. Repetitively engaging in sexual fantasies, urges or behaviors in response to dysphoric mood states (e.g., anxiety, depression, boredom, irritability). 3. -

The Routledge International Handbook of Sexual Addiction

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 25 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge International Handbook of Sexual Addiction Thaddeus Birchard, Joanna Benfield Sexual addiction Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315639512.ch1_3 Gerard A. Schaefer, Christoph J. Ahlers Published online on: 13 Sep 2017 How to cite :- Gerard A. Schaefer, Christoph J. Ahlers. 13 Sep 2017, Sexual addiction from: The Routledge International Handbook of Sexual Addiction Routledge Accessed on: 25 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315639512.ch1_3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 21 1.3 Sexual addiction Terminology, definitions and conceptualisation Gerard A. Schaefer and Christoph J. Ahlers The phenomenon of concern In 1986 the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) devoted an issue of their bimonthly report (with contributions by Patrick J. -

Mixed Methods Analysis of Counselor Views, Attitudes and Perceived Competencies Regarding the Treatment of Internet Pornography Addiction

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2013 Mixed Methods Analysis of Counselor Views, Attitudes and Perceived Competencies Regarding the Treatment of Internet Pornography Addiction Bradly K. Hinman Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Counseling Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hinman, Bradly K., "Mixed Methods Analysis of Counselor Views, Attitudes and Perceived Competencies Regarding the Treatment of Internet Pornography Addiction" (2013). Dissertations. 207. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/207 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MIXED METHODS ANALYSIS OF COUNSELOR VIEWS, ATTITUDES AND PERCEIVED COMPETENCIES REGARDING THE TREATMENT OF INTERNET PORNOGRAPHY ADDICTION by Bradly K. Hinman A dissertation submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Counselor Education and Counseling Psychology Western Michigan University December 2013 Doctoral Committee: Gary H. Bischof, Ph.D., Chair Alan Hovestadt, Ed.D. Karen Blaisure, Ph.D. MIXED METHODS ANALYSIS OF COUNSELOR VIEWS, ATTITUDES AND PERCEIVED COMPETENCIES REGARDING THE TREATMENT OF INTERNET PORNOGRAPHY -

Welcome to the IRI 7-‐Step Training for Therapists

Welcome to the IRI 7-Step Training For Therapists Version: 3.0 Date: May 2015 Course Tools: http://infidelityrecoveryinstitute.com/7-step-infidelity-recovery- program-proFessional-training/ © Copyright 2015 by The Infidelity Recovery Institute, all rights reserved 2 Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 The 7-Step InFidelity Recovery Model ................................................................................................................................... 6 The 7 Types oF AFFairs ................................................................................................................................................................... 6 What Is The Infidelity Recovery Model? ......................................................................................... 7 General InFormation: ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 General Purpose: ............................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Terms .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 Goals of training ........................................................................................................................................ -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) This is Pop…XTC (3/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Airport…Motors (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) Roxanne…The Police (2/79) Lucky Number (slavic dance version)…Lene Lovich (3/79) Good Times Roll…The Cars (3/79) Dance -

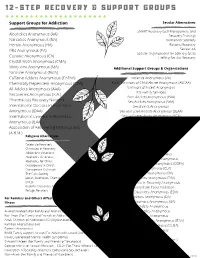

12-Step Recovery Groups

1 2 - S T E P R E C O V E R Y & S U P P O R T G R O U P S Support Groups for Addiction Secular Alternatives SMART Recovery (Self-Management and Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) Recovery Training) Narcotics Anonymous (NA) Women for Sobriety Heroin Anonymous (HA) Rational Recovery Pills Anonymous (PA) Secular AA Secular Organizations for Sobriety (SOS) Cocaine Anonymous (CA) LifeRing Secular Recovery Crystal Meth Anonymous (CMA) Marijuana Anonymous (MA) Additional Support Groups & Organizations Nicotine Anonymous (NicA) Caffeine Addicts Anonymous (CAFAA) Violence Anonymous (VA) Chemically Dependent Anonymous (CDA) Adult Survivors of Child Abuse Anonymous (ASCAA) All Addicts Anonymous (AAA) Survivors of Incest Anonymous lDS Family Services Recoveries Anonymous (R.A.) Porn Addicts Anonymous (PAA) Pharmacists Recovery Network Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) International Doctors in Alcoholics Sexaholics Anonymous Anonymous (IDAA) Sex and Love Addicts Anonymous (SLAA) International Lawyers in Alcoholics Sexual Compulsives Anonymous (SCA) Anonymous (ILAA) Sexual Recovery ANonymous (SRA) Association of Recovering Motorcyclists Co-dependents Anonymous (CoDa) Emotions Anonymous (A.R.M.) Religious Alternatives Dual Recovery Anonymous Depressed Anonymous Celebrate Recovery Social Anxiety Anonymous Christians in Recovery PTSD Anonymous Addictions Victorious Self Mutilators Anonymous Alcoholics Victorious Obsessive Compulsive Anonymous Alcoholics for Christ Obsessive Skin Pickers Anonymous (OSPA) Overcomers in Christ Overcomers Outreach Clutters Anonymous (CLA) -

The Pornography Pandemic: Implications, Scope and Solutions for the Church in the Post-Internet Age

Southeastern University FireScholars Selected Honors Theses Spring 2018 THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE Dillon A. Diaz Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Diaz, Dillon A., "THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE" (2018). Selected Honors Theses. 127. https://firescholars.seu.edu/honors/127 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PORNOGRAPHY PANDEMIC: IMPLICATIONS, SCOPE AND SOLUTIONS FOR THE CHURCH IN THE POST-INTERNET AGE by Dillon Amadeus Diaz Submitted to the Honors Program Committee in partial fulfillment of the requirements for University Honors Scholars Southeastern University 2018 Diaz 1 Copyright by Dillon Amadeus Diaz 2018 Diaz 2 Dedication To Dr. Gordon Miller, whose Thesis class I accidentally missed on the 12th of March, 2018. I asked if I missed anything important; he replied, “Of course you missed something important. My class is always important.” To Dr. Joseph Davis, my thesis advisor and greatest inspiration in the defense of the true faith, whose words still ring true in my ears: “You either worship a God of revelation, or a God of imagination.” To Abigail Sprinkle, my beautiful bride-to-be, lovely beyond compare. One night, I told her every wicked thing I had ever done, and she looked at me with a smile that betrayed everything I had just confessed. -

UN Imposes Air Embargo on Iraq 1 Inside Candidates for Senate Offer

rTHE TUFTS DAILY? Medford, MA 02155 Wednesday, September 26,1990 Vol XXI, Number 14 Children IA WINNING START I Candidates for Senate victims of offer views on issues AIDS virus MASSPIRG, Financial aid debated GENEVA (AP)-- The virus by CONSTANTINE ATHANAS ter Somtino, Jessica Foster, Adam that causes AIDS is likely to have Scnior Staff Writer Tratt, Silvana Nardone, Peter spread to at least 10 million chil- Freshmen and sophomore Cushing, Allison Feiner, Michael dren by the end of the century, the candidates for open seats on the Plotnick, Jeff Ehrenkranz, Mona World Health Organization said Tufts Community Union Senate Fetouh, Robert Zucker, Scott Tuesday. discussed several issues includ- Noonan, Gregory Bedward, and An additional 10 million chil- ing funding for the Massachu- Vaughn Minassian are the 18 can- dren will have lost their parents setts Public Interest Research didates for the seven open fresh- to the deadly disease, a WHO Group, freedom of speech, and men seats on the Senate. official said. increased financial aid at an open Among several students who Dr. Michael Merson said most forum held in Hotung Cafe Mon- spoke about MASSPIRG, Toby victims would be in the Third Photo by Pam Yudin day. * Yim said that the Senate should World, where AIDS would be- With a 3-1 record, the men’s soccer team is off to its best start in sophomores Melissa Channing have tighter controls on funding come a major child killer, revers- recent history. Yesterday, the team defeated the BrandeisJudges, and Meredith Hennessey are the and should not fund groups that ing progress made in improving 3-2. -

DAN KELLY's Ipod 80S PLAYLIST It's the End of The

DAN KELLY’S iPOD 80s PLAYLIST It’s The End of the 70s Cherry Bomb…The Runaways (9/76) Anarchy in the UK…Sex Pistols (12/76) X Offender…Blondie (1/77) See No Evil…Television (2/77) Police & Thieves…The Clash (3/77) Dancing the Night Away…Motors (4/77) Sound and Vision…David Bowie (4/77) Solsbury Hill…Peter Gabriel (4/77) Sheena is a Punk Rocker…Ramones (7/77) First Time…The Boys (7/77) Lust for Life…Iggy Pop (9/7D7) In the Flesh…Blondie (9/77) The Punk…Cherry Vanilla (10/77) Red Hot…Robert Gordon & Link Wray (10/77) 2-4-6-8 Motorway…Tom Robinson (11/77) Rockaway Beach…Ramones (12/77) Statue of Liberty…XTC (1/78) Psycho Killer…Talking Heads (2/78) Fan Mail…Blondie (2/78) Who’s Been Sleeping Here…Tuff Darts (4/78) Because the Night…Patty Smith Group (4/78) Touch and Go…Magazine (4/78) Ce Plane Pour Moi…Plastic Bertrand (4/78) Do You Wanna Dance?...Ramones (4/78) The Day the World Turned Day-Glo…X-Ray Specs (4/78) The Model…Kraftwerk (5/78) Keep Your Dreams…Suicide (5/78) Miss You…Rolling Stones (5/78) Hot Child in the City…Nick Gilder (6/78) Just What I Needed…The Cars (6/78) Pump It Up…Elvis Costello (6/78) Sex Master…Squeeze (7/78) Surrender…Cheap Trick (7/78) Top of the Pops…The Rezillos (8/78) Another Girl, Another Planet…The Only Ones (8/78) All for the Love of Rock N Roll…Tuff Darts (9/78) Public Image…PIL (10/78) I Wanna Be Sedated (megamix)…The Ramones (10/78) My Best Friend’s Girl…the Cars (10/78) Here Comes the Night…Nick Gilder (11/78) Europe Endless…Kraftwerk (11/78) Slow Motion…Ultravox (12/78) I See Red…Split Enz (12/78) Roxanne…The