A Stable Sub-Complex Between GCP4, GCP5 and GCP6 Promotes The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sirt1 Is Regulated by Mir-135A and Involved in DNA Damage Repair During Mouse Cellular Reprogramming

www.aging-us.com AGING 2020, Vol. 12, No. 8 Research Paper Sirt1 is regulated by miR-135a and involved in DNA damage repair during mouse cellular reprogramming Andy Chun Hang Chen1,2,*, Qian Peng2,*, Sze Wan Fong1, William Shu Biu Yeung1,2, Yin Lau Lee1,2 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China 2Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Fertility Regulation, The University of Hong Kong Shenzhen Hospital, Shenzhen, China *Co-first authors Correspondence to: Yin Lau Lee, William Shu Biu Yeung; email: [email protected], [email protected] Keywords: mouse induced pluripotent stem cells, cellular reprogramming, Sirt1, miR-135a, DNA damage repair Received: December 30, 2019 Accepted: March 30, 2020 Published: April 26, 2020 Copyright: Chen et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Sirt1 facilitates the reprogramming of mouse somatic cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). It is regulated by micro-RNA and reported to be a target of miR-135a. However, their relationship and roles on cellular reprogramming remain unknown. In this study, we found negative correlations between miR-135a and Sirt1 during mouse embryonic stem cells differentiation and mouse embryonic fibroblasts reprogramming. We further found that the reprogramming efficiency was reduced by the overexpression of miR-135a precursor but induced by the miR-135a inhibitor. Co-immunoprecipitation followed by mass spectrometry identified 21 SIRT1 interacting proteins including KU70 and WRN, which were highly enriched for DNA damage repair. -

Microtubule Nucleation Remote from Centrosomes May Explain

Microtubule nucleation remote from centrosomes may INAUGURAL ARTICLE explain how asters span large cells Keisuke Ishiharaa,b,1, Phuong A. Nguyena,b, Aaron C. Groena,b, Christine M. Fielda,b, and Timothy J. Mitchisona,b,1 aDepartment of Systems Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; and bMarine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA 02543 This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2014. Edited by Ronald D. Vale, Howard Hughes Medical Institute and University of California, San Francisco, CA, and approved November 13, 2014 (received for review October 6, 2014) A major challenge in cell biology is to understand how nanometer- aster growth in large cells, such as microtubule sliding, tread- sized molecules can organize micrometer-sized cells in space and milling, or nucleation remote from centrosomes. time. One solution in many animal cells is a radial array of Previously we developed a cell-free system to reconstitute microtubules called an aster, which is nucleated by a central cleavage furrow signaling where growing asters interacted (5, organizing center and spans the entire cytoplasm. Frog (here 12). Here, we combine cell-free reconstitution and quantitative Xenopus laevis) embryos are more than 1 mm in diameter and imaging to identify microtubule nucleation away from the cen- divide with a defined geometry every 30 min. Like smaller cells, trosome as the key biophysical mechanism underlying aster they are organized by asters, which grow, interact, and move to growth. We propose that aster growth in large cells should be precisely position the cleavage planes. -

Role of Nucleation in Cortical Microtubule Array Organization: Variations on a Theme Erica A

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations Biology 7-2013 Role of nucleation in cortical microtubule array organization: variations on a theme Erica A. Fishel Washington University in St Louis Ram Dixit Washington University in St Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bio_facpubs Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Biology Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Fishel, Erica A. and Dixit, Ram, "Role of nucleation in cortical microtubule array organization: variations on a theme" (2013). Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations. 37. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bio_facpubs/37 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Title: Role of nucleation in cortical microtubule array organization: variations on a theme Authors: Erica A. Fishel and Ram Dixit Running title: Microtubule nucleation in the CMT array Key words: Noncentrosomal microtubules, γ-tubulin, Arabidopsis thaliana, Branching microtubules, Computer simulations, Interphase Corresponding Author: Ram Dixit Biology Department Washington University in St. Louis One Brookings Drive, CB 1137 St. Louis, MO 63130. Phone: (314) 935-8823 Fax: (314) 935-4432 Email: [email protected] 2 Abstract The interphase cortical microtubules (CMTs) of plant cells form strikingly ordered arrays in the absence of a dedicated microtubule-organizing center. Considerable effort has focused on activities such as bundling and severing that occur after CMT nucleation and are thought to be important for generating and maintaining ordered arrays. -

Microtubule Nucleation by Γ-Tubulin Complexes

REVIEWS Microtubule nucleation by γ‑tubulin complexes Justin M. Kollman*, Andreas Merdes‡, Lionel Mourey§ and David A. Agard* Abstract | Microtubule nucleation is regulated by the γ‑tubulin ring complex (γTuRC) and related γ‑tubulin complexes, providing spatial and temporal control over the initiation of microtubule growth. Recent structural work has shed light on the mechanism of γTuRC-based microtubule nucleation, confirming the long-standing hypothesis that the γTuRC functions as a microtubule template. The first crystallographic analysis of a non-γ‑tubulin γTuRC component (γ‑tubulin complex protein 4 (GCP4)) has resulted in a new appreciation of the relationships among all γTuRC proteins, leading to a refined model of their organization and function. The structures have also suggested an unexpected mechanism for regulating γTuRC activity via conformational modulation of the complex component GCP3. New experiments on γTuRC localization extend these insights, suggesting a direct link between its attachment at specific cellular sites and its activation. 4 Microtubule catastrophe The microtubule cytoskeleton is critically important in vitro from purified tubulin . In vivo, though, almost The rapid depolymerization of for the spatial and temporal organization of eukaryotic all microtubules have 13 protofilaments5–7, suggesting microtubules that occurs when cells, playing a central part in functions as diverse as that one level of cellular control involves defining unique GTP has been hydrolysed in all intracellular transport, organelle positioning, motil‑ microtubule geometry. The 13‑fold symmetry is probably tubulin subunits up to the growing tip. ity, signalling and cell division. The ability to play this preferred because it is the only geometry in which proto‑ range of parts requires microtubules to be arranged in filaments run straight along the microtubule length, as complex arrays that are capable of rapid reorganization. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A. -

Microtubule Organization and Microtubule- Associated Proteins (Maps)

Chapter 3 Microtubule Organization and Microtubule- Associated Proteins (MAPs) Elena Tortosa, Lukas C. Kapitein, and Casper C. Hoogenraad Abstract Dendrites have a unique microtubule organization. In vertebrates, den- dritic microtubules are organized in antiparallel bundles, oriented with their plus ends either pointing away or toward the soma. The mixed microtubule arrays control intracellular trafficking and local signaling pathways, and are essential for dendrite development and function. The organization of microtubule arrays largely depends on the combined function of different microtubule regulatory factors or generally named microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs). Classical MAPs, also called structural MAPs, were identified more than 20 years ago based on their ability to bind to and copurify with microtubules. Most classical MAPs bind along the microtubule lattice and regulate microtubule polymerization, bundling, and stabilization. Recent evidences suggest that classical MAPs also guide motor protein transport, interact with the actin cytoskeleton, and act in various neuronal signaling networks. Here, we give an overview of microtubule organization in dendrites and the role of classical MAPs in dendrite development, dendritic spine formation, and synaptic plasticity. Keywords Neuron • Dendrite • Cytoskeleton • Microtubule • Microtubule- associated protein • MAP1 • MAP2 • MAP4 • MAP6 • MAP7 • MAP9 • Tau 3.1 Introduction Microtubules (MTs) are cytoskeletal structures that play essential roles in all eukaryotic cells. MTs are important not only during cell division but also in non-dividing cells, where they are critical structures in numerous cellular processes such as cell motility, migration, differentiation, intracellular transport and organelle positioning. MTs are composed of two proteins, α- and β-tubulin, that form heterodimers and organize themselves in a head-to-tail manner. -

Downloaded 10 April 2020)

Breeze et al. Genome Medicine (2021) 13:74 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-021-00877-z RESEARCH Open Access Epigenome-wide association study of kidney function identifies trans-ethnic and ethnic-specific loci Charles E. Breeze1,2,3* , Anna Batorsky4, Mi Kyeong Lee5, Mindy D. Szeto6, Xiaoguang Xu7, Daniel L. McCartney8, Rong Jiang9, Amit Patki10, Holly J. Kramer11,12, James M. Eales7, Laura Raffield13, Leslie Lange6, Ethan Lange6, Peter Durda14, Yongmei Liu15, Russ P. Tracy14,16, David Van Den Berg17, NHLBI Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) Consortium, TOPMed MESA Multi-Omics Working Group, Kathryn L. Evans8, William E. Kraus15,18, Svati Shah15,18, Hermant K. Tiwari10, Lifang Hou19,20, Eric A. Whitsel21,22, Xiao Jiang7, Fadi J. Charchar23,24,25, Andrea A. Baccarelli26, Stephen S. Rich27, Andrew P. Morris28, Marguerite R. Irvin29, Donna K. Arnett30, Elizabeth R. Hauser15,31, Jerome I. Rotter32, Adolfo Correa33, Caroline Hayward34, Steve Horvath35,36, Riccardo E. Marioni8, Maciej Tomaszewski7,37, Stephan Beck2, Sonja I. Berndt1, Stephanie J. London5, Josyf C. Mychaleckyj27 and Nora Franceschini21* Abstract Background: DNA methylation (DNAm) is associated with gene regulation and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), a measure of kidney function. Decreased eGFR is more common among US Hispanics and African Americans. The causes for this are poorly understood. We aimed to identify trans-ethnic and ethnic-specific differentially methylated positions (DMPs) associated with eGFR using an agnostic, genome-wide approach. Methods: The study included up to 5428 participants from multi-ethnic studies for discovery and 8109 participants for replication. We tested the associations between whole blood DNAm and eGFR using beta values from Illumina 450K or EPIC arrays. -

Dynein Activators and Adaptors at a Glance Mara A

© 2019. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Cell Science (2019) 132, jcs227132. doi:10.1242/jcs.227132 CELL SCIENCE AT A GLANCE Dynein activators and adaptors at a glance Mara A. Olenick and Erika L. F. Holzbaur* ABSTRACT ribonucleoprotein particles for BICD2, and signaling endosomes for Cytoplasmic dynein-1 (hereafter dynein) is an essential cellular motor Hook1. In this Cell Science at a Glance article and accompanying that drives the movement of diverse cargos along the microtubule poster, we highlight the conserved structural features found in dynein cytoskeleton, including organelles, vesicles and RNAs. A long- activators, the effects of these activators on biophysical parameters, standing question is how a single form of dynein can be adapted to a such as motor velocity and stall force, and the specific intracellular wide range of cellular functions in both interphase and mitosis. functions they mediate. – Recent progress has provided new insights dynein interacts with a KEY WORDS: BICD2, Cytoplasmic dynein, Dynactin, Hook1, group of activating adaptors that provide cargo-specific and/or Microtubule motors, Trafficking function-specific regulation of the motor complex. Activating adaptors such as BICD2 and Hook1 enhance the stability of the Introduction complex that dynein forms with its required activator dynactin, leading Microtubule-based transport is vital to cellular development and to highly processive motility toward the microtubule minus end. survival. Microtubules provide a polarized highway to facilitate Furthermore, activating adaptors mediate specific interactions of the active transport by the molecular motors dynein and kinesin. While motor complex with cargos such as Rab6-positive vesicles or many types of kinesins drive transport toward microtubule plus- ends, there is only one major form of dynein, cytoplasmic dynein-1, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA 19104, which drives the trafficking of a wide array of minus-end-directed USA. -

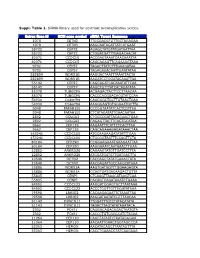

Suppl. Table 1

Suppl. Table 1. SiRNA library used for centriole overduplication screen. Entrez Gene Id NCBI gene symbol siRNA Target Sequence 1070 CETN3 TTGCGACGTGTTGCTAGAGAA 1070 CETN3 AAGCAATAGATTATCATGAAT 55722 CEP72 AGAGCTATGTATGATAATTAA 55722 CEP72 CTGGATGATTTGAGACAACAT 80071 CCDC15 ACCGAGTAAATCAACAAATTA 80071 CCDC15 CAGCAGAGTTCAGAAAGTAAA 9702 CEP57 TAGACTTATCTTTGAAGATAA 9702 CEP57 TAGAGAAACAATTGAATATAA 282809 WDR51B AAGGACTAATTTAAATTACTA 282809 WDR51B AAGATCCTGGATACAAATTAA 55142 CEP27 CAGCAGATCACAAATATTCAA 55142 CEP27 AAGCTGTTTATCACAGATATA 85378 TUBGCP6 ACGAGACTACTTCCTTAACAA 85378 TUBGCP6 CACCCACGGACACGTATCCAA 54930 C14orf94 CAGCGGCTGCTTGTAACTGAA 54930 C14orf94 AAGGGAGTGTGGAAATGCTTA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CCCGGTAATATCACTCGTTAA 5048 PAFAH1B1 CTCATAGATATTGAACAATAA 2802 GOLGA3 CTGGCCGATTACAGAACTGAA 2802 GOLGA3 CAGAGTTACTTCAGTGCATAA 9662 CEP135 AAGAATTTCATTCTCACTTAA 9662 CEP135 CAGCAGAAAGAGATAAACTAA 153241 CCDC100 ATGCAAGAAGATATATTTGAA 153241 CCDC100 CTGCGGTAATTTCCAGTTCTA 80184 CEP290 CCGGAAGAAATGAAGAATTAA 80184 CEP290 AAGGAAATCAATAAACTTGAA 22852 ANKRD26 CAGAAGTATGTTGATCCTTTA 22852 ANKRD26 ATGGATGATGTTGATGACTTA 10540 DCTN2 CACCAGCTATATGAAACTATA 10540 DCTN2 AACGAGATTGCCAAGCATAAA 25886 WDR51A AAGTGATGGTTTGGAAGAGTA 25886 WDR51A CCAGTGATGACAAGACTGTTA 55835 CENPJ CTCAAGTTAAACATAAGTCAA 55835 CENPJ CACAGTCAGATAAATCTGAAA 84902 CCDC123 AAGGATGGAGTGCTTAATAAA 84902 CCDC123 ACCCTGGTTGTTGGATATAAA 79598 LRRIQ2 CACAAGAGAATTCTAAATTAA 79598 LRRIQ2 AAGGATAATATCGTTTAACAA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TTGGATTTGTCTATACATATA 51143 DYNC1LI1 TAGACTTAGTATATAAATACA 2302 FOXJ1 CAGGACAGACAGACTAATGTA -

The Cytoskeleton

The Cytoskeleton •Organizes and stabilizes cells •Pulls chromosomes apart •Drives intracellular traffic •Supports plasma membrane and nuclear envelope •Enables cellular movement •Guides growth of the plant cell wall •Provides machinery for muscle contraction and nerve cell extension •Controls the amazing diversity of eukaryotic cell shapes Three major types of cytoskeleton •Microtubules •Actin Filaments (Microfilaments) •Intermediate Filaments (still debated for plants) •Cytoskeleton can be visualizes simply by staining for protein - Coomassie blue here. All filaments are assembled from smaller protein sububits Sububits of filaments: Actin for Microfilaments Tubulin for Microtubules IF protein for IFs “Cytoskeletal systems are dynamic and adaptable, organized more like an ant trail than like interstate highways”. Microtubules - Tubulin Microfilaments -Actin Intermediate Filaments Evolutionary Conservation •Actin and tubulins are highly conserved among organisms. •Actin amino acid sequence is usually 90% identical (great control antibody!). •IF proteins less conserved. Cytoplasmic IF proteins mostly in metazoan lines, nuclear IF proteins (lamins) more widely conserved, possibly ancestral. •Actin and MTs bind to so many proteins that sequence might be very constrained. Concepts: Thermal stability and structure Structure of MT and MF allows for both stability and dynamic ends. Structure of IF more “rope-like” due to staggered long subunits. ATP binding to actin promotes its polymerization Treadmilling Concepts: Two ends of filament have different on/off rates (due to conformation of monomers. Monomer carries NTF (Actin: ATP, tubulin: GTP). Slow hydrolysis occurs in polymer. Critical concentration is different for plus and minus end: Results in net assembly at plus end and net disassembly at minus end. Treadmilling of a microtubule in vivo Microinjection of rhodamin-labeleld tubulin (1:20 with unlabeled tubulin). -

Effector Gene Expression Potential to Th17 Cells by Promoting Microrna

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 26, 2021 is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology published online 17 May 2013 from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2013/05/17/jimmun ol.1300351 MicroRNA-155 Confers Encephalogenic Potential to Th17 Cells by Promoting Effector Gene Expression Ruozhen Hu, Thomas B. Huffaker, Dominique A. Kagele, Marah C. Runtsch, Erin Bake, Aadel A. Chaudhuri, June L. Round and Ryan M. O'Connell J Immunol Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2013/05/17/jimmunol.130035 1.DC1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2013 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 26, 2021. Published May 17, 2013, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300351 The Journal of Immunology MicroRNA-155 Confers Encephalogenic Potential to Th17 Cells by Promoting Effector Gene Expression Ruozhen Hu,* Thomas B. Huffaker,* Dominique A. Kagele,* Marah C. Runtsch,* Erin Bake,* Aadel A. Chaudhuri,† June L. -

The Alter Retina: Alternative Splicing of Retinal Genes in Health and Disease

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The Alter Retina: Alternative Splicing of Retinal Genes in Health and Disease Izarbe Aísa-Marín 1,2 , Rocío García-Arroyo 1,3 , Serena Mirra 1,2 and Gemma Marfany 1,2,3,* 1 Departament of Genetics, Microbiology and Statistics, Avda. Diagonal 643, Universitat de Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (I.A.-M.); [email protected] (R.G.-A.); [email protected] (S.M.) 2 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Enfermedades Raras (CIBERER), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII), Universitat de Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain 3 Institute of Biomedicine (IBUB, IBUB-IRSJD), Universitat de Barcelona, 08028 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Alternative splicing of mRNA is an essential mechanism to regulate and increase the diversity of the transcriptome and proteome. Alternative splicing frequently occurs in a tissue- or time-specific manner, contributing to differential gene expression between cell types during development. Neural tissues present extremely complex splicing programs and display the highest number of alternative splicing events. As an extension of the central nervous system, the retina constitutes an excellent system to illustrate the high diversity of neural transcripts. The retina expresses retinal specific splicing factors and produces a large number of alternative transcripts, including exclusive tissue-specific exons, which require an exquisite regulation. In fact, a current challenge in the genetic diagnosis of inherited retinal diseases stems from the lack of information regarding alternative splicing of retinal genes, as a considerable percentage of mutations alter splicing Citation: Aísa-Marín, I.; or the relative production of alternative transcripts. Modulation of alternative splicing in the retina García-Arroyo, R.; Mirra, S.; Marfany, is also instrumental in the design of novel therapeutic approaches for retinal dystrophies, since it G.