1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pastsearch Newsletter Issue 102: June 2021

PastSearch Newsletter Issue 102: June 2021 Welcome to PastSearch Newsletter You can find a downloadable version at www.pastsearch-archaeo-history.co.uk May Round Up...................1 York: The Story of its Walls May Round Up Bars and Castles – The Normans (part 5)……….....2 St. John’s Dance……..……6 This Month in History.....................7 British Monarchs ...............8 HOSM Local History Society...................10 Bishops Palace Community Dig & Howdenshire Archaeological Society …………………………11 Managed to get out and complete a site in Holme-on Spalding Moor Picture This........................12 area, unfortunately after another few days of rain, so very soggy. Just For Fun.......................12 Thankfully the machine driver was able to scrape the slop away to Just for Fun make a route through for me between the seven trenches. Answers.................13 Dates for Diary…………..13 Although Holme-on Spalding Moor parish has a lot of archaeology, PastSearch YouTube there were only land drains encountered in these trenches, which must Channel………………..…13 have been blocked, considering the amount of surface water. What’s Been in the News..............14 Adverts..............................15 Zoom Talks this month looked at the 1984 York Minster Fire, which completed the series of three talks. Also the history of British coins, from the Celtic Potins (c.80BC), through the centuries, noting the new introductions and those taken out of circulation to the 20th century and decimalization. For June and July Zoom Talks see ‘Dates for Diary’ on page 13 and Adverts on pages 15-18. Or go directly to the PastSeach Eventbrite page to find all the talks as they are added. -

Forn Sigulfsson and Ivo Fitz Forn 1

20 OCTOBER 2014 FORN SIGULFSSON AND IVO FITZ FORN 1 Release date Version notes Who Current version: H1-Forn Sigulfsson 20/10/2014 Original version DC, HD and Ivo fitz Forn-2014- 1 Previous versions: ———— This text is made available through the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs License; additional terms may apply Authors for attribution statement: Charters of William II and Henry I Project David X Carpenter, Faculty of History, University of Oxford Hugh Doherty, University of East Anglia FORN SIGULFSSON AND IVO FITZ FORN Tenants-in-chief in Yorkshire, Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumberland Archive of the Dacre family, Narworth Forn Sigulfsson and his son Ivo were important landholders in northern England during the reign of Henry I, but nothing can be said with confidence of Forn or his antecedents before that.1 Forn first occurs, as ‘Forna Sigulfi filio’, witnessing Ranulf Meschin’s deed giving to Abbot Stephen and St Mary’s Abbey the manor of Wetheral (Ctl. Wetherhal, 1– 5, no. 1; Sharpe, St Mary’s Abbey, Deeds, X; see also Headnote for Wetheral priory). The date must be before Christmas 1113, when Stephen’s successor Richard was appointed. St Mary’s soon established a dependent priory at Wetheral, which lies some five miles east of Carlisle. Forn’s attestion, between Waltheof fitz Gospatric and Ketel son of Eltred, indicates he was already an important force in Cumbria. We may speculate, from the name he gave to his only known son Ivo, that he 1 C. Phythian-Adams is not the first to propose a connection with Sigulf, named in a pre-Conquest Cumbrian writ in the name of Gospatric, but this may be no more than a coincidence of names (C. -

The Holinshed Editors: Religious Attitudes and Their Consequences

The Holinshed editors: religious attitudes and their consequences By Felicity Heal Jesus College, Oxford This is an introductory lecture prepared for the Cambridge Chronicles conference, July 2008. It should not be quoted or cited without full acknowledgement. Francis Thynne, defending himself when writing lives of the archbishops of Canterbury, one of sections of the 1587 edition of Holinshed that was censored, commented : It is beside my purpose, to treat of the substance of religion, sith I am onelie politicall and not ecclesiasticall a naked writer of histories, and not a learned divine to treat of mysteries of religion.1 And, given the sensitivity of any expression of religious view in mid-Elizabethan England, he and his fellow-contributors were wise to fall back, on occasions, upon the established convention that ecclesiastical and secular histories were in two separate spheres. It is true that the Chronicles can appear overwhelmingly secular, dominated as they are by scenes of war and political conflict. But of course Thynne did protest too much. No serious chronicler could avoid giving the history of the three kingdoms an ecclesiastical dimension: the mere choice of material proclaimed religious identity and, among their other sources, the editors drew extensively upon a text that did irrefutably address the ‘mysteries of religion’ – Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.2 Moreover, in a text as sententious as Holinshed the reader is constantly led in certain interpretative directions. Those directions are superficially obvious – the affirmation 1 Citations are to Holinshed’s Chronicles , ed. Henry Ellis, 6 vols. (London, 1807-8): 4:743 2 D.R.Woolf, The Idea of History in Early Stuart England (Toronto, 1990), ch 1 1 of the Protestant settlement, anti-Romanism and a general conviction about the providential purposes of the Deity for Englishmen. -

The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service

Quidditas Volume 9 Article 9 1988 The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Platt, F. Jeffrey (1988) "The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service," Quidditas: Vol. 9 , Article 9. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol9/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. JRMMRA 9 (1988) The Elizabethan Diplomatic Service by F. Jeffrey Platt Northern Arizona University The critical early years of Elizabeth's reign witnessed a watershed in European history. The 1559 Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis, which ended the long Hapsburg-Valois conflict, resulted in a sudden shift in the focus of international politics from Italy to the uncomfortable proximity of the Low Countries. The arrival there, 30 miles from England's coast, in 1567, of thousands of seasoned Spanish troops presented a military and commer cial threat the English queen could not ignore. Moreover, French control of Calais and their growing interest in supplanting the Spanish presence in the Netherlands represented an even greater menace to England's security. Combined with these ominous developments, the Queen's excommunica tion in May 1570 further strengthened the growing anti-English and anti Protestant sentiment of Counter-Reformation Europe. These circumstances, plus the significantly greater resources of France and Spain, defined England, at best, as a middleweight in a world dominated by two heavyweights. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

Two Elizabethan Women Correspondence of Joan and Maria Thynne 1575-1611

%iltalJir2 imzturh éutietp (formerly the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society) VOLUME XXXVIII FOR THE YEAR 1982 THIS VOLUME IS PUBLISHED WITH THE HELP OF A GRANT FROM THE LATE MISS ISOBEL THORNLEY'S BEQUEST TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Impression of 450 copies TWO ELIZABETHAN WOMEN CORRESPONDENCE OF JOAN AND MARIA THYNNE 1575-1611 EDITED BY ALISON D. WALL DEVIZES 1983 © Wiltshire Record Society ISBN: 0 901333 15 8 Set in Times New Roman 10/1 lpt. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY J. G. FENN LTD. (Print Division) STOKE-ON-TRENT STAFFS. CONTENTS Frontispiece P4895 ii. vi Ralph Bernard Pugh ix Preface xi Abbreviations xiii List of Frequently Mentioned Persons xv INTRODUCTION Joan Hayward and the Thynne Marriage xvii Expansion to Caus Castle xxii A Secret Marriage xxv The Documents and Editorial Method xxxii THE LETTERS, nos. 1 to 68 I APPENDIX Other Relevant Letters, nos. 69 to 75 54 Joan Thynne’s Will, no. 76 61 INDEX OF PERSONS AND PLACES 63 INDEX OF SUBJECTS 70 List of Members 72 Publications of the Society 78 RALPH BERNARD PUGH Ralph Bernard Pugh, President of the Wiltshire Record Society, died on 3rd December 1982. Ralph Pugh was the principal founder of the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, which in 1967 became the Wiltshire Record Society. Editing the first volume himself he remained general editor and honorary secretary of the Branch until 1953. From that date until his death he was continuously Chairman of the Branch, and President of the Society. Three further volumes were edited by himself, and in every other one he took a close personal interest. -

Notices of the Family of Buckler

Cfje JFamtlj of iSucfeler* Üuclertana * NOTICES OF THE FAMILY OF COLLECTED BY CHARLES ALBAN BUCKLER, A.D. 1880. jfav |3rtbate CLtrculatton. LONDON: MITCHELL AND HUGHES, 140 WARDOUR STREET, W. 1886. 1910181 Eijese lotoljj offspring of the mini a frtenolg Bucftler fain tooulo finö; Beneath its shelter let them Lie, Suil then the critics' shaft oefg, c IMITATED FROM PARKHUBST BY J. E. MILLARD, D.D. f J ïntrotmctíom THE Family of Buckler is of Norman origin, from Rouen and its vicinity, where the name is preserved in Ecclesiastical Records of early date. The surname was one easily Anglicised, and variously spelt Bucler, Boclar, Bokeler, Bukeler, Boucler, Buckler, and in English signifies a shield. The Bucklers appear to have settled in Hampshire soon after the Norman Conquest, and subsequently in Dorsetshire, where they were located at the time of the Heralds' Visitations in 1565 and 1623, about which period a younger branch was firmly established at Warminster in the county of Wilts. In a beautiful valley on the banks of the Beaulieu river or Boldre Water is Buckler's hard, a populous village, principally inhabited by workmen employed in shipbuilding. Many frigates and men-of-war have been built there, the situation being very convenient for the purpose, and the tide forming a fine bay at high water. The word hard signifies a causeway made upon the mud for the purpose of landing. ('Beauties of England and Wales.') PEDIGREE Butfcler ot Causetoap antr Wolcnmije JHaltrafcus, to* Borget, CONTINUED FROM THE HERALDS' VISITATIONS OP A.D. 1565 AND A.D. 1623. L ARMS.—Sable, on a fesse between three dragons' heads erased or, as many estoiles of eight points of the field. -

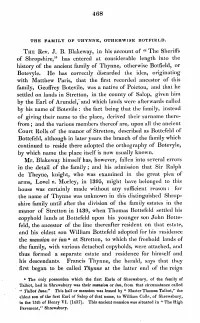

The Sheriffs of Shropshire," Has Entered at Considerable Length Into the History of the Ancient Family of Thynne, Otherwise Botfield, Or Botevyle

468 THE FAMILY OF 'l'HYNNE, OTHERWISE BO'l'FIELD. THE Rev. J. B. Blakeway, in his account of "The Sheriffs of Shropshire," has entered at considerable length into the history of the ancient family of Thynne, otherwise Botfield, or Botevyle. He has correctly discarded the idea, originating with Matthew Paris, that the first recorded ancestor of this family, Geoffrey Botevile, was a native of Poictou, and that he settled on lands in Stretton, in the county of Salop, given him by the Earl of Arundel,' .and which lands were afterwards called by his name of Botevile: the fact being that the family, instead of giving their name to the place, derived their surname there• from; and the various members thereof are, upon all the ancient Court Rolls of the manor of Stretton, described as Bottefeld of Bottefeld, although in later years the branch of the family which continued to reside there adopted the orthography of Botevyle, by which name the place itself is now usually known. Mr. Blakeway himself has, however, fallen into several errors in the detail of the family; and his admission that Sir Ralph de Theyne, knight, who was examined in the great plea of arms, Lovel v. Morley, in 1395, might have belonged to this house was certainly made without any sufficient reason : for the name of Thynne was unknown in this distinguished Shrop• shire family until after the division of the family estates in the manor of Stretton in 1439, when Thomas Bottefeld settled his copyhold lands at Bottefeld upon his younger son John Botte• feld, the ancestor of the line thereafter resident on that estate, and his eldest son William Bottefeld adopted for his residence the mansion or inn a at Stretton, to which the freehold lands of the family, with various detached copyholds, were attached, and thus formed a separate estate and residence for himself and his descendants. -

The Misfortunes of Arthur and Its Extensive Links to a Whole Range of His Other Shakespeare Plays

FRANCIS BACON AND HIS FIRST UNACKNOWLEDGED SHAKESPEARE PLAY THE MISFORTUNES OF ARTHUR AND ITS EXTENSIVE LINKS TO A WHOLE RANGE OF HIS OTHER SHAKESPEARE PLAYS By A Phoenix It is an immense ocean that surrounds the island of truth Francis Bacon If circumstances lead me I will find Where truth is hid, though it were hid indeed Within the centre [Hamlet: 2:2: 159-61] Tempore Patet Occulta Veritas (In Time the Hidden Truth will be Revealed) Francis Bacon 1 CONTENTS 1. The Silence of the Bacon Editors and Biographers 4 2. The So-called Contributors of The Misfortunes of Arthur 7 3. The Background of The Misfortunes of Arthur 28 4. The Political Allegory of The Misfortunes of Arthur 41 5. Francis Bacon Sole Author of The Misfortunes of Arthur 47 6. The Misfortunes of Arthur and the Shakespeare Plays 57 References 102 2 FACSIMILES Fig. 1 The Title Page of The Misfortunes of Arthur 52 Fig. 2 The First Page of the Introduction 53 Fig. 3 The Last Page of the Introduction 54 Fig. 4 The Page naming Hughes as the Principal Author 55 Fig. 5 The Final Page of The Misfortunes of Arthur 56 [All Deciphered] 3 1. THE SILENCE OF THE BACON EDITORS AND BIOGRAPHERS In normal circumstances any drama with any kind of proximity to the Shakespeare plays however remote or tenuous would ordinarily attract the attention of biographers, editors and commentators in their battalions. Who would individually and collectively scrutinize it for all traces, echoes, parallels, mutual links, and any and all connections to the hallowed Shakespeare canon. -

J\S-Aacj\ Cwton "Wallop., $ Bl Sari Of1{Ports Matd/I

:>- S' Ui-cfAarria, .tffzatirU&r- J\s-aacj\ cwton "Wallop., $ bL Sari of1 {Ports matd/i y^CiJixtkcr- ph JC. THE WALLOP FAMILY y4nd Their Ancestry By VERNON JAMES WATNEY nATF MICROFILMED iTEld #_fe - PROJECT and G. S ROLL * CALL # Kjyb&iDey- , ' VOL. 1 WALLOP — COLE 1/7 OXFORD PRINTED BY JOHN JOHNSON Printer to the University 1928 GENEALOGirA! DEPARTMENT CHURCH ••.;••• P-. .go CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Omnes, si ad originem primam revocantur, a dis sunt. SENECA, Epist. xliv. One hundred copies of this work have been printed. PREFACE '•"^AN these bones live ? . and the breath came into them, and they ^-^ lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.' The question, that was asked in Ezekiel's vision, seems to have been answered satisfactorily ; but it is no easy matter to breathe life into the dry bones of more than a thousand pedigrees : for not many of us are interested in the genealogies of others ; though indeed to those few such an interest is a living thing. Several of the following pedigrees are to be found among the most ancient of authenticated genealogical records : almost all of them have been derived from accepted and standard works ; and the most modern authorities have been consulted ; while many pedigrees, that seemed to be doubtful, have been omitted. Their special interest is to be found in the fact that (with the exception of some of those whose names are recorded in the Wallop pedigree, including Sir John Wallop, K.G., who ' walloped' the French in 1515) every person, whose lineage is shown, is a direct (not a collateral) ancestor of a family, whose continuous descent can be traced since the thirteenth century, and whose name is identical with that part of England in which its members have held land for more than seven hundred and fifty years. -

The Elizabethan Court Day by Day--1589

1589 1589 At RICHMOND PALACE, Surrey. Jan 1,Wed New Year gifts. Among 185 gifts to the Queen: by Sir Thomas Heneage: ‘One jewel of gold like an Alpha and Omega with sparks of diamonds’; by William Dethick, Garter King of Arms: ‘A Book of Arms of the Noblemen in Henry the Fifth’s time’; by John Smithson, Master Cook: ‘One fair marchpane [marzipan] with St George in the midst’; NYG by Petruccio Ubaldini: ‘A book covered with vellum of Italian. Also Jan 1: play, by the Children of Paul’s.T Jan 1, London, Jean Morel dedicated to the Queen: De Ecclesia ab Antechristo liberanda. [Of the Church, liberated from Anti-Christ]. Epistle to the Queen, praising her for her victories over all enemies, through God’s guidance. Preface to the Reader. Text: 104p. (London, 1589). Jan 1, Thomas Churchyard dedicated to the Queen: ‘A Rebuke to Rebellion’, in verse. [Modern edition: Nichols, Progresses (2014), iii.470-480]. Jan 5: Anthony Bridgeman, of Mitcheldean, Gloucs, to the Queen: ‘Sacred and most gracious Queen may it please your Majesty to accept as a New Year’s gift at the hands of me your most humble poor subject these thirteen branches...to be planted in this your Highness’s garden of England’. Each ‘branch’ being a proposed religious or social reform, including: ‘A restraint of the profaning of the Sabbath Day especially with minstrelsey, baiting of bears and other beasts, and such like’. ‘A restraint of publishing profane poetry, books of profane songs, sonnets, pamphlets and such like’. ‘That there be no book, pamphlet, sonnet, ballad or libel printed or written of purpose either to be sold or openly published without your Majesty’s licence’. -

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti Eethelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi

Sanctity in Tenth-Century Anglo-Latin Hagiography: Wulfstan of Winchester's Vita Sancti EEthelwoldi and Byrhtferth of Ramsey's Vita Sancti Oswaldi Nicola Jane Robertson Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds, Centre for Medieval Studies, September 2003 The candidate confinns that the work submitted is her own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Mary Swan and Professor Ian Wood for their guidance and support throughout the course of this project. Professor Wood's good-natured advice and perceptive comments have helped guide me over the past four years. Dr Swan's counsel and encouragement above and beyond the call of duty have kept me going, especially in these last, most difficult stages. I would also like to thank Dr William Flynn, for all his help with my Latin and useful commentary, even though he was not officially obliged to offer it. My advising tutor Professor Joyce Hill also played an important part in the completion of this work. I should extend my gratitude to Alison Martin, for a constant supply of stationery and kind words. I am also grateful for the assistance of the staff of the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds. I would also like to thank all the students of the Centre for Medieval Studies, past and present, who have always offered a friendly and receptive environment for the exchange of ideas and assorted cakes.