Names and Arms Clauses. Howard V Howard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Forn Sigulfsson and Ivo Fitz Forn 1

20 OCTOBER 2014 FORN SIGULFSSON AND IVO FITZ FORN 1 Release date Version notes Who Current version: H1-Forn Sigulfsson 20/10/2014 Original version DC, HD and Ivo fitz Forn-2014- 1 Previous versions: ———— This text is made available through the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs License; additional terms may apply Authors for attribution statement: Charters of William II and Henry I Project David X Carpenter, Faculty of History, University of Oxford Hugh Doherty, University of East Anglia FORN SIGULFSSON AND IVO FITZ FORN Tenants-in-chief in Yorkshire, Cumberland, Westmorland and Northumberland Archive of the Dacre family, Narworth Forn Sigulfsson and his son Ivo were important landholders in northern England during the reign of Henry I, but nothing can be said with confidence of Forn or his antecedents before that.1 Forn first occurs, as ‘Forna Sigulfi filio’, witnessing Ranulf Meschin’s deed giving to Abbot Stephen and St Mary’s Abbey the manor of Wetheral (Ctl. Wetherhal, 1– 5, no. 1; Sharpe, St Mary’s Abbey, Deeds, X; see also Headnote for Wetheral priory). The date must be before Christmas 1113, when Stephen’s successor Richard was appointed. St Mary’s soon established a dependent priory at Wetheral, which lies some five miles east of Carlisle. Forn’s attestion, between Waltheof fitz Gospatric and Ketel son of Eltred, indicates he was already an important force in Cumbria. We may speculate, from the name he gave to his only known son Ivo, that he 1 C. Phythian-Adams is not the first to propose a connection with Sigulf, named in a pre-Conquest Cumbrian writ in the name of Gospatric, but this may be no more than a coincidence of names (C. -

The Construction of Northumberland House and the Patronage of Its Original Builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1603–14

The Antiquaries Journal, 90, 2010,pp1 of 60 r The Society of Antiquaries of London, 2010 doi:10.1017⁄s0003581510000016 THE CONSTRUCTION OF NORTHUMBERLAND HOUSE AND THE PATRONAGE OF ITS ORIGINAL BUILDER, LORD HENRY HOWARD, 1603–14 Manolo Guerci Manolo Guerci, Kent School of Architecture, University of Kent, Marlowe Building, Canterbury CT27NR, UK. E-mail: [email protected] This paper affords a complete analysis of the construction of the original Northampton (later Northumberland) House in the Strand (demolished in 1874), which has never been fully investigated. It begins with an examination of the little-known architectural patronage of its builder, Lord Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton from 1603, one of the most interesting figures of the early Stuart era. With reference to the building of the contemporary Salisbury House by Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, the only other Strand palace to be built in the early seventeenth century, textual and visual evidence are closely investigated. A rediscovered eleva- tional drawing of the original front of Northampton House is also discussed. By associating it with other sources, such as the first inventory of the house (transcribed in the Appendix), the inside and outside of Northampton House as Henry Howard left it in 1614 are re-configured for the first time. Northumberland House was the greatest representative of the old aristocratic mansions on the Strand – the almost uninterrupted series of waterfront palaces and large gardens that stretched from Westminster to the City of London, the political and economic centres of the country, respectively. Northumberland House was also the only one to have survived into the age of photography. -

Jetanh. 34253 FRIDAY, 7 FEBRUARY, 1936

JEtanh. 34253 801 Registered as a newspaper # * Table of Contents see last page FRIDAY, 7 FEBRUARY, 1936 Heralds College, Rouge Dragon Pursuivant, London. E. N. Geijer, Esq. 22nd January, 1936. York Herald, A. J. Toppin, Esq. THE PROCLAMATION OF HIS MAJESTY KING EDWARD VIII. Windsor Herald, In pursuance of the Order in Council of the A. T. Butler, Esq. 21st January, His Majesty's Officers of Arms Richmond Herald, this day made Proclamation declaring the H. R. C. Martin, Esq. Accession of His Majesty King Edward VIIT. At ten o'clock the Officers of Arms, habited Chester Herald, in their Tabards, assembled at St. James's J. D. Heaton-Armstrong, Esq. Palace and, attended by the Serjeants at Arms, Somerset Herald, proceeded to the balcony in Friary Court, where, after the trumpets had sounded thrice, The Hon. George Bellew. the Proclamation was read by Sir Gerald W. Lancaster Herald, Wollaston, K.C.V.O., Garter Principal King A. G. B. Russell, Esq. of Arms. A procession was then formed in the following order, the Kings of Arms, Heralds, Norroy King of Arms, and Pursuivants and the Serjeants at Arms Major A. H. S. Howard. being in Royal carriages. Clarenceux King of Arms, An Escort of Royal Horse Guards. A. W. S. Cochrane, Esq. The High Bailiff of Westminster, in his The Procession moved on to Charing Cross, carriage. where the Proclamation was read the second State Trumpeters. time by Lancaster Herald, and then moved on to the site of Temple Bar, where a temporary Serjeants at Arms, bearing their maces. -

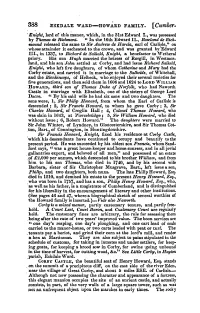

Charles Howard, of Croglin Hall

• 388 ESKDALE WARD HOWARD FAMILY. [Cumber- ' . ·Knight, lord of this inanor, which, in the 31st Edwa~d I., was possessed by Thomas de Richmont. " In the 16th Edward 11., Rowland de Rich mound released the same to Sir Andrew de Harcla, earl of Carlisle," on . whose attainder it escheated to the crown, and was granted by 'Edward Ill., in 1337, to Richard de Salkeld, Knight, a benefactor to Wetheral priory. His son Hugh married the heiress of Rosgill, in 'Vestmor. land, and his son John settled at Corby, and had issue Richard Salkeld, Knight" who left five daughters, of whom Catherine and Mary had the Corby estate, and carried it in marriage to the Salkelds, of Whitehall, and the Blenkinsops, of Helbeck, who.enjoyed their several moieties for five generations, and then sold them in 1606 and 1624 to LoRD WILLIAJ!I ·HoWARD, third son of Thomas Duke of Norfolk, who had Naworth Castle in marriage with Elizabeth, one of the sisters of George Lord Dacre. " By his said wife he had six sons and two daughters. The sons were, 1, Sir Philip Howard, from whom the Earl of Carlisle is descended; 2, Sir Francis Howard, to whom he gave Corby; 3, Sir · Charles Howard, of Croglin Hall; 4, Colonel Thomas Howard, who was slain in 1643, at Piercebridge; 5, Sir William Howard, who died without issue; 6, Robert Howard." The daughters were married to Sir John "\\rinter, of Lyndney, in Gloucestershire, and Sir Thomas Cot. _ton, Bart., of Connington, in Huntingdonshire. Sir Francis Howard, Knight, fixed his residence at Corby Castle, :whicnhis descendants have continued to occupy and beautify to the present period. -

1 Aldred/Nattes/RS Corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1

1 Tittler Roberts:1 Aldred/Nattes/RS corr 27/12/10 13:14 Page 1 Volume XI, No. 2 The BRITISH ART Journal Discovering ‘T. Leigh’ Tracking the elusive portrait painter through Stuart England and Wales1 Stephanie Roberts & Robert Tittler 1 Robert Davies III of Gwysaney by Thomas Leigh, 1643. Oil on canvas, 69 x 59 cm. National Museum Wales, Cardiff. With permission of Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales n a 1941 edition of The Oxford Journal, Maurice 2 David, 1st Earl Barrymore by Thomas Leigh, 1636. Oil on canvas, 88 x 81 Brockwell, then Curator of the Cook Collection at cm. Current location unknown © Christie’s Images Ltd 2008 IDoughty House in Richmond, Surrey, submitted the fol- lowing appeal for information: [Brockwell’s] vast amount of data may not amount to much T. LEIGH, PORTRAIT-PAINTER, 1643. Information is sought in fact,’5 but both agreed that the little available information regarding the obscure English portrait-painter T. Leigh, who on Leigh was worth preserving nonetheless. Regrettably, signed, dated and suitably inscribed a very limited number of Brockwell’s original notes are lost to us today, and since then pictures – and all in 1643. It is strange that we still know nothing no real attempt has been made to further identify Leigh, until about his origin, place and date of birth, residence, marriage and now. death… Much research proves that the biographical facts Brockwell eventually sold the portrait of Robert Davies to regarding T. Leigh recited in the Burlington Magazine, 1916, xxix, the National Museum of Wales in 1948, thus bringing p.3 74, and in Thieme Becker’s Allgemeines Lexikon of 1928 are ‘Thomas Leigh’ to national attention as a painter of mid-17th too scanty and not completely accurate. -

The Life of Philip Thomas Howard, OP, Cardinal of Norfolk

lllifa Ex Lrauis 3liiralw* (furnlu* (JlnrWrrp THE LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CARDINAL OF NORFOLK. [The Copyright is reserved.] HMif -ft/ tutorvmjuiei. ifway ROMA Pa && Urtts.etOrl,,* awarzK ^n/^^-hi fofmmatafttrpureisJPTUS oJeffe Chori quo lufas mane<tt Ifouigionis THE LIFE OP PHILIP THOMAS HOWAKD, O.P. CARDINAL OF NORFOLK, GRAND ALMONER TO CATHERINE OF BRAGANZA QUEEN-CONSORT OF KING CHARLES II., AND RESTORER OF THE ENGLISH PROVINCE OF FRIAR-PREACHERS OR DOMINICANS. COMPILED FROM ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS. WITH A SKETCH OF THE EISE, MISSIONS, AND INFLUENCE OF THE DOMINICAN OEDEE, AND OF ITS EARLY HISTORY IN ENGLAND, BY FE. C. F, EAYMUND PALMEE, O.P. LONDON: THOMAS KICHAKDSON AND SON; DUBLIN ; AND DERBY. MDCCCLXVII. TO HENRY, DUKE OF NORFOLK, THIS LIFE OF PHILIP THOMAS HOWARD, O.P., CAEDINAL OF NOEFOLK, is AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED IN MEMORY OF THE FAITH AND VIRTUES OF HIS FATHEE, Dominican Priory, Woodchester, Gloucestershire. PREFACE. The following Life has been compiled mainly from original records and documents still preserved in the Archives of the English Province of Friar-Preachers. The work has at least this recommendation, that the matter is entirely new, as the MSS. from which it is taken have hitherto lain in complete obscurity. It is hoped that it will form an interesting addition to the Ecclesiastical History of Eng land. In the acknowledging of great assist ance from several friends, especial thanks are due to Philip H. Howard, Esq., of Corby Castle, who kindly supplied or directed atten tion to much valuable matter, and contributed a short but graphic sketch of the Life of the Cardinal of Norfolk taken by his father the late Henry Howard, Esq., from a MS. -

Harleian Society Publications

HARLEIAN SOCIETY Register Section Leveson Gower, G.W.G. ed., A register of all the christninges, burialles and weddings, within the parish of Saint Peeters upon Cornhill beginning at the raigne of our most soueraigne ladie Queen Elizabeth. Part I, Harleian Society Register Section, 1 (1877) Hovenden, R. ed., A register of all the christninges, marriages and burialls, within the precinct of the cathedral and metropoliticall church of Christe of Canterburie, Harleian Society Register Section, 2 (1878) Chester, J.L. ed., The reiester booke of Saynte De’nis Backchurch parishe for maryages, christenynges and buryalles begynnynge in the yeare of o’lord God 1538, Harleian Society Register Section, 3 (1878) Leveson Gower, G.W.G. ed., A register of all the christninges, burialles and weddings, within the parish of Saint Peeters upon Cornhill beginning at the raigne of our most soueraigne ladie Queen Elizabeth. Part II, Harleian Society Register Section, 4 (1879) Chester, J.L. ed., The parish registers of St. Mary Aldermary, London, containing the marriages, baptisms and burials from 1558 to 1754, Harleian Society Register Section, 5 (1881) Chester, J.L. ed., The parish registers of St. Thomas the Apostle, London, containing the marriages, baptisms and burials from 1558 to 1754, Harleian Society Register Section, 6 (1881) Chester, J.L. ed., The parish registers of St. Michael, Cornhill, London, containing the marriages, baptisms and burials from 1546 to 1754, Harleian Society Register Section, 7 (1882) Chester, J.L. with Armytage, Gen. J ed., The parish registers of St. Antholin, Budge Row, London, containing the marriages, baptisms and burials from 1538 to 1754; and of St. -

Hrmorial Bearing Grantcfc to Tbe Gown of Hiverpool

HiverpooL 179?- of March, Gown 2jrd tbe to patent, original grantcfc the from Bearing Facsimile Hrmorial TRANSACTIONS. THE ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CITY OF LIVERPOOL.* By J. Paul Rylands, F.S.A. WITH A REPORT THEREON ISY GEORGE WILLIAM MARSHALL, LL.D., F.S.A., ROUGE CROIX PURSUIVANT OF ARMS. Read 2oth November, 1890. N The Stranger in Liverpool; or an historical and I descriptive view of the town of Liverpool and its environs the twelfth edition Liverpool: printed and sold by Thos. Kaye, Castle Street; i~$J<S, the following foot-note to a description of the armorial ensigns of the town of Liverpool occurs : " The coat and crest of the town of Liverpool, "as by Flower, (No. 2167) who was herald for " Lancashire argent, and in base, water proper, " standing in which a wild drake sable, beaked "gules crest a heron sable, in its beak gules, a " branch of lever virt. In some of the old books " of the Corporation, about 1611, the town's arms " are said to be a cormorant. In the year 1667 " the Earl of Derby gave the town ' a large mace * At the meeting at which this paper was read the original patents of the Arms of Liverpool and Birkenhead were exhibited. 2 Armorial Bearings of Liverpool. " ' of silver, richly gilt, and engraved with his " ' Majesty's arms and the arms of the town, viz. " ' a leaver.' " This suggested the idea that the town might have had a grant of armorial bearings, or a recognition of a right to bear arms, long anterior to the grant of the arms now borne by the City of Liverpool, the patent for which is dated the 22nd March, 1797. -

The University of Hull the Early Career of Thomas

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL THE EARLY CAREER OF THOMAS, LORD HOWARD, EARL OF SURREY AND THIRD DUKE OF NORFOLK, 1474—c. 1525 being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Susan Elisabeth Vokes, B.A. September, 1988 Acknowledgements I should like to thank the University of Hull for my postgraduate scholarship, and the Institute of Historical Research and Eliot College, the Universiy of Kent, for providing excellent facilities in recent years. I am especially grateful to the Duke of Norfolk and his archivists for giving me access to material in his possession. The staff of many other archives and libraries have been extremely helpful in answering detailed enquiries and helping me to locate documents, and / regret that it is not possible to acknowledge them individually. I am grateful to my supervisor, Peter Heath, for his patience, understanding and willingness to read endless drafts over the years in which this study has evolved. Others, too, have contributed much. Members of the Russell/Starkey seminar group at the Institute of Historical Research, and the Late Medieval seminar group at the University of Kent made helpful comments on a paper, and I have benefitted from suggestions, discussion, references and encouragement from many others, particularly: Neil Samman, Maria Dowling, Peter Gwynn, George Bernard, Greg Walker and Diarmaid MacCulloch. I am particularly grateful to several people who took the trouble to read and comment on drafts of various chapters. Margaret Condon and Anne Crawford commented on a draft of the first chapter, Carole Rawcliffe and Linda Clerk on my analysis of Norfolk's estate accounts, Steven Ellis on my chapters on Surrey in Ireland and in the north of England, and Roger Virgoe on much of the thesis, including all the East Anglian material. -

6242 Supplement to the London Gazette, 20 November, 1953

6242 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, 20 NOVEMBER, 1953 THE LORD HIGH CHANCELLOR The Lord Simonds attended by his Pursebearer T. Cokayne, Esq. his coronet carried by his page Andrew Parker-Bowles, Esq. THE CROSS OF CANTERBURY borne by the Reverend John S. Long, M.A. THE ARCHBISHOP OF CANTERBURY The Most Reverend Geoffrey Francis Fisher, D.D. attended by the Reverend Eric G. Jay, Ph.D. and the Reverend Canon I. H. White-Thomson, M.A. ARUNDEL HERALD EXTRAORDINARY NORFOLK HERALD EXTRAORDINARY Dermot Morrah, Esq. H. S. London, Esq. SOMERSET HERALD LYON KING OF ARMS WINDSOR HERALD M. R. Trappes-Lomax, Esq. Sir Thomas Innes of Learney, R. P. Graham-Vivian, Esq., K.C.V.O. M.C. The Harbinger (Major- ADMIRAL OF THE FLEET The Standard Bearer Genefal Arthur Chater, HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS (Major-General Hon. C.B., D.S.O., O.B.E.) THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH, Maurice Wingfield, and Three Gentlemen-at-Arms K.G., K.T., G.M.B.E. C.M.G., D.S.O.) and Three his coronet carried by his page Gentlemen-at-Arms MJ. N. G. Rees, Midshipman, R.N. THE EQUERRY TO THE THE TREASURER TO THE THE PRIVATE SECRETARY TO THE DUKE OF EDINBURGH DUKE OF EDINBURGH DUKE OF EDINBURGH Squadron-Leader Lieut-General Sir Lieut.-Commander Beresford Horsley, A.F.C. Frederick Browning, K.B.E., Michael Parker, M.V.O., C.B., D.S.O. R.N. SERJEANT-AT-ARMS SERJEANT-AT-ARMS Lieut.-Commander (S) George A. Titman, Esq., C.B.E., M.V.O. Albert W. -

Subject Indexes

Subject Indexes. p.4: Accession Day celebrations (November 17). p.14: Accession Day: London and county index. p.17: Accidents. p.18: Accounts and account-books. p.20: Alchemists and alchemy. p.21: Almoners. p.22: Alms-giving, Maundy, Alms-houses. p.25: Animals. p.26: Apothecaries. p.27: Apparel: general. p.32: Apparel, Statutes of. p.32: Archery. p.33: Architecture, building. p.34: Armada; other attempted invasions, Scottish Border incursions. p.37: Armour and armourers. p.38: Astrology, prophecies, prophets. p.39: Banqueting-houses. p.40: Barges and Watermen. p.42: Battles. p.43: Birds, and Hawking. p.44: Birthday of Queen (Sept 7): celebrations; London and county index. p.46: Calendar. p.46: Calligraphy and Characterie (shorthand). p.47: Carts, carters, cart-takers. p.48: Catholics: selected references. p.50: Census. p.51: Chapel Royal. p.53: Children. p.55: Churches and cathedrals visited by Queen. p.56: Church furnishings; church monuments. p.59: Churchwardens’ accounts: chronological list. p.72: Churchwardens’ accounts: London and county index. Ciphers: see Secret messages, and ciphers. p.76: City and town accounts. p.79: Clergy: selected references. p.81: Clergy: sermons index. p.88: Climate and natural phenomena. p.90: Coats of arms. p.92: Coinage and coins. p.92: Cooks and kitchens. p.93: Coronation. p.94: Court ceremonial and festivities. p.96: Court disputes. p.98: Crime. p.101: Customs, customs officers. p.102: Disease, illness, accidents, of the Queen. p.105: Disease and illness: general. p.108: Disease: Plague. p.110: Disease: Smallpox. p.110: Duels and Challenges to Duels.