The Holinshed Editors: Religious Attitudes and Their Consequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Genre and Identity in British and Irish National Histories, 1541-1691

“NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 A dissertation presented by Sarah Elizabeth Connell to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2014 1 “NO ROOM IN HISTORY”: GENRE AND IDENTIY IN BRITISH AND IRISH NATIONAL HISTORIES, 1541-1691 by Sarah Elizabeth Connell ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2014 2 ABSTRACT In this project, I build on the scholarship that has challenged the historiographic revolution model to question the valorization of the early modern humanist narrative history’s sophistication and historiographic advancement in direct relation to its concerted efforts to shed the purportedly pious, credulous, and naïve materials and methods of medieval history. As I demonstrate, the methodologies available to early modern historians, many of which were developed by medieval chroniclers, were extraordinary flexible, able to meet a large number of scholarly and political needs. I argue that many early modern historians worked with medieval texts and genres not because they had yet to learn more sophisticated models for representing the past, but rather because one of the most effective ways that these writers dealt with the political and religious exigencies of their times was by adapting the practices, genres, and materials of medieval history. I demonstrate that the early modern national history was capable of supporting multiple genres and reading modes; in fact, many of these histories reflect their authors’ conviction that authentic past narratives required genres with varying levels of facticity. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

Two Elizabethan Women Correspondence of Joan and Maria Thynne 1575-1611

%iltalJir2 imzturh éutietp (formerly the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society) VOLUME XXXVIII FOR THE YEAR 1982 THIS VOLUME IS PUBLISHED WITH THE HELP OF A GRANT FROM THE LATE MISS ISOBEL THORNLEY'S BEQUEST TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON Impression of 450 copies TWO ELIZABETHAN WOMEN CORRESPONDENCE OF JOAN AND MARIA THYNNE 1575-1611 EDITED BY ALISON D. WALL DEVIZES 1983 © Wiltshire Record Society ISBN: 0 901333 15 8 Set in Times New Roman 10/1 lpt. PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY J. G. FENN LTD. (Print Division) STOKE-ON-TRENT STAFFS. CONTENTS Frontispiece P4895 ii. vi Ralph Bernard Pugh ix Preface xi Abbreviations xiii List of Frequently Mentioned Persons xv INTRODUCTION Joan Hayward and the Thynne Marriage xvii Expansion to Caus Castle xxii A Secret Marriage xxv The Documents and Editorial Method xxxii THE LETTERS, nos. 1 to 68 I APPENDIX Other Relevant Letters, nos. 69 to 75 54 Joan Thynne’s Will, no. 76 61 INDEX OF PERSONS AND PLACES 63 INDEX OF SUBJECTS 70 List of Members 72 Publications of the Society 78 RALPH BERNARD PUGH Ralph Bernard Pugh, President of the Wiltshire Record Society, died on 3rd December 1982. Ralph Pugh was the principal founder of the Records Branch of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, which in 1967 became the Wiltshire Record Society. Editing the first volume himself he remained general editor and honorary secretary of the Branch until 1953. From that date until his death he was continuously Chairman of the Branch, and President of the Society. Three further volumes were edited by himself, and in every other one he took a close personal interest. -

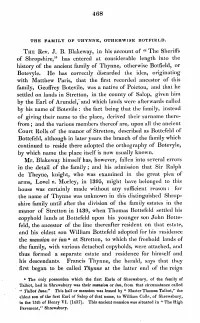

The Sheriffs of Shropshire," Has Entered at Considerable Length Into the History of the Ancient Family of Thynne, Otherwise Botfield, Or Botevyle

468 THE FAMILY OF 'l'HYNNE, OTHERWISE BO'l'FIELD. THE Rev. J. B. Blakeway, in his account of "The Sheriffs of Shropshire," has entered at considerable length into the history of the ancient family of Thynne, otherwise Botfield, or Botevyle. He has correctly discarded the idea, originating with Matthew Paris, that the first recorded ancestor of this family, Geoffrey Botevile, was a native of Poictou, and that he settled on lands in Stretton, in the county of Salop, given him by the Earl of Arundel,' .and which lands were afterwards called by his name of Botevile: the fact being that the family, instead of giving their name to the place, derived their surname there• from; and the various members thereof are, upon all the ancient Court Rolls of the manor of Stretton, described as Bottefeld of Bottefeld, although in later years the branch of the family which continued to reside there adopted the orthography of Botevyle, by which name the place itself is now usually known. Mr. Blakeway himself has, however, fallen into several errors in the detail of the family; and his admission that Sir Ralph de Theyne, knight, who was examined in the great plea of arms, Lovel v. Morley, in 1395, might have belonged to this house was certainly made without any sufficient reason : for the name of Thynne was unknown in this distinguished Shrop• shire family until after the division of the family estates in the manor of Stretton in 1439, when Thomas Bottefeld settled his copyhold lands at Bottefeld upon his younger son John Botte• feld, the ancestor of the line thereafter resident on that estate, and his eldest son William Bottefeld adopted for his residence the mansion or inn a at Stretton, to which the freehold lands of the family, with various detached copyholds, were attached, and thus formed a separate estate and residence for himself and his descendants. -

Archbishop of Canterbury, and One of the Things This Meant Was That Fruit Orchards Would Be Established for the Monasteries

THE ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY And yet — in fact you need only draw a single thread at any point you choose out of the fabric of life and the run will make a pathway across the whole, and down that wider pathway each of the other threads will become successively visible, one by one. — Heimito von Doderer, DIE DÂIMONEN “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Archbishops of Canterb HDT WHAT? INDEX ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY 597 CE Christianity was established among the Anglo-Saxons in Kent by Augustine (this Roman import to England was of course not the Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo in Africa who had been in the ground already for some seven generations — and therefore he is referred to sometimes as “St. Augustine the Less”), who in this year became the 1st Archbishop of Canterbury, and one of the things this meant was that fruit orchards would be established for the monasteries. Despite repeated Viking attacks many of these survived. The monastery at Ely (Cambridgeshire) would be particularly famous for its orchards and vineyards. DO I HAVE YOUR ATTENTION? GOOD. Archbishops of Canterbury “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY 604 CE May 26, 604: Augustine died (this Roman import to England was of course not the Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo in Africa who had been in the ground already for some seven generations — and therefore he is referred to sometimes as “St. Augustine the Less”), and Laurentius succeeded him as Archbishop of Canterbury. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Archbishops of Canterbury – Universities Attended Abbreviations: B

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Archbishops of Canterbury – Universities attended abbreviations: b. = born. c or c. = circa. e = education. e. = educated. esp. = especially. nr. = near. s = school. (ap) = apparently. (pr) = probably. (ps) = possibly. (r) = reputedly. 105th 2013- Justin Portal Welby (b. 1956) Trinity College Cambridge BA 78; St John’s College Durham BA 91. 104th 2002-2012 Rowan Douglas Williams (b. 1950) Christ’s College Cambridge BA 71, MA 75; Wadham College, Oxford DPhil 75; DD 89. 103rd 1991-2002 George Leonard Carey (b.1935) London College of Divinity. King's College London. Associate of the London College of Divinity 1st class 1961, BD Hons 1962 (London), MTh1965 (London), PhD1971 (London). 102nd 1980-1991 Robert Alexander Kennedy Runcie (1921-2000) Brasenose College Oxford (1 year). Sandhurst (trained for Guards Armoured Division). Brasenose College Oxford. BA (1st class lit. hum) 1948, MA 1948. 101st 1974-1980 Frederick Donald Coggan (1909-2000) St John's College Cambridge. 1st class oriental languages tripos part i 1930, BA (1st class oriental languages tripos part ii), MA 1935. 100th 1961-1974 Arthur Michael Ramsey (1904-1988) Magdalene College Cambridge. 2nd class classical tripos part i 1925, BA (1st class theological tripos part i) 1927, MA1930, BD1950. 99th 1945-1961 Geoffrey Francis Fisher (1887-1972) Exeter College Oxford. 1st class classical honour moderations 1908, BA (1st class literae humaniores) 1910, 1st class theology 1911, MA1913. 98th 1942-1944 William Temple (1881-1944) Balliol College Oxford. 1st class honour moderations 1902 & literae humaniores 1904. 97th 1928-1941 William Cosmo Gordon Lang (1864-1945) Glasgow. MA. Balliol College Oxford. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article. -

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print Author(S): Louise M

Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print Author(s): Louise M. Bishop Source: The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Vol. 106, No. 3 (Jul., 2007), pp. 336- 363 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27712660 . Accessed: 25/10/2011 14:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of English and Germanic Philology. http://www.jstor.org Father Chaucer and the Vivification of Print Louise M. Bishop, Robert D. Clark Honors College, University of Oregon Even in the fifteenth century, Chaucer was seen by his countrymen as the was preeminent English poet, the father, as Dryden to call him in 1700, of English poetry.1 Despite general agreement in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries Thomas about Chaucer's poetic preeminence, however, Speght's edition of Chaucer's Works (1598, STC 5077, 5078, 5079; 1602, STC 5080, 5081)2 adds elaborate textual apparatus?illustrated frontispieces, life i. Ethan Knapp, The Bureaucratic Muse: Thomas Hoccleve and the Literature of Late Medieval England (University Park, PA: Penn State Univ. -

El Código Secreto Del Esopete Ystoriado En El Contexto De La Exégesis Literaria Y Su Evolución Hacia Un Método Científico Tardomedieval

El Código Secreto del Esopete Ystoriado en el Contexto de la Exégesis Literaria y su Evolución Hacia un Método Científico Tardomedieval Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Anchondo, Luis Adrian Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 08/10/2021 19:39:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/314672 EL CÓDIGO SECRETO DEL ESOPETE YSTORIADO EN EL CONTEXTO DE LA EXÉGESIS LITERARIA Y SU EVOLUCIÓN HACIA UN MÉTODO CIENTÍFICO TARDOMEDIEVAL by Luis Anchondo __________________________ Copyright © Luis Anchondo 2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN SPANISH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Luis Anchondo, titled “El código secreto del Esopete ystoriado en el contexto de la exégesis literaria y su evolución hacia un método científico tardomedieval” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________________________________________________ Date: Richard P. Kinkade _______________________________________________________________________ Date: Malcolm Compitello _______________________________________________________________________ Date: Eliud Chuffe Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’.