Managing Turmoil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journaux Journals

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 37th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 37e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 12 No 12 Tuesday, February 13, 2001 Le mardi 13 février 2001 10:00 a.m. 10 heures The Clerk informed the House of the unavoidable absence of the Le Greffier informe la Chambre de l’absence inévitable du Speaker. Président. Whereupon, Mr. Kilger (Stormont — Dundas — Charlotten- Sur ce, M. Kilger (Stormont — Dundas — Charlottenburgh), burgh), Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees of the Vice–président et président des Comités pléniers, assume la Whole, took the Chair, pursuant to subsection 43(1) of the présidence, conformément au paragraphe 43(1) de la Loi sur le Parliament of Canada Act. Parlement du Canada. PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES PRESENTING REPORTS FROM COMMITTEES PRÉSENTATION DE RAPPORTS DE COMITÉS Mr. Lee (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of the M. Lee (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Government in the House of Commons), from the Standing Chambre des communes), du Comité permanent de la procédure et Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, presented the des affaires de la Chambre, présente le 1er rapport de ce Comité, 1st Report of the Committee, which was as follows: dont voici le texte : The Committee recommends, pursuant to Standing Orders 104 Votre Comité recommande, conformément au mandat que lui and 114, that the list of members and associate members for confèrent les articles 104 et 114 du Règlement, que la liste -

House & Senate

HOUSE & SENATE COMMITTEES / 63 HOUSE &SENATE COMMITTEES ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PRIVACY AND Meili Faille, Vice-Chair (BQ)......................47 A complete list of all House Standing Andrew Telegdi, Vice-Chair (L)..................44 and Sub-Committees, Standing Joint ETHICS / L’ACCÈS À L’INFORMATION, DE LA PROTECTION DES RENSEIGNEMENTS Omar Alghabra, Member (L).......................38 Committees, and Senate Standing Dave Batters, Member (CON) .....................36 PERSONNELS ET DE L’ÉTHIQUE Committees. Includes the committee Barry Devolin, Member (CON)...................40 clerks, chairs, vice-chairs, and ordinary Richard Rumas, Committee Clerk Raymond Gravel, Member (BQ) .................48 committee members. Phone: 613-992-1240 FAX: 613-995-2106 Nina Grewal, Member (CON) .....................32 House of Commons Committees Tom Wappel, Chair (L)................................45 Jim Karygiannis, Member (L)......................41 Directorate Patrick Martin, Vice-Chair (NDP)...............37 Ed Komarnicki, Member (CON) .................36 Phone: 613-992-3150 David Tilson, Vice-Chair (CON).................44 Bill Siksay, Member (NDP).........................33 Sukh Dhaliwal, Member (L)........................32 FAX: 613-996-1962 Blair Wilson, Member (IND).......................33 Carole Lavallée, Member (BQ) ...................48 Senate Committees and Private Glen Pearson, Member (L) ..........................43 ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE Legislation Branch Scott Reid, Member (CON) .........................43 DEVELOPMENT / ENVIRONNEMENT -

Rare Artifact Found and Donated to Local Museum

News Volume 54 • Issue 44 • November 8, 2019 1 -“Delivering The Contact news and information. At home and around the world.” • “Transmettre des nouvelles et de l’information, d’ici et d’ailleurs.” November 08, 2019 CHRISTINASELLSQUINTE Christina Charbonneau Sales Representative Certified Negotiation Expert (CNE1) #3 Ranked Agent* - EXIT Realty Group - 2017 to 2019, Trenton S e r v i n g 8 W i n g / C F B T r e n t o n • 8 e E s c a d re / B F C T r e n t o n • h t t p : // t h e c o n t a c t n e w s p a p e r . c f b t r e n t o n . c o m *Ranked in the Top 3 for 1st Quarter, 2019 436 Transport Squadron Cell: 613-243-0037 Address: 309 Dundas Street East, INSIDE Quinte West, K8V 1M1 th BRONZE AWARD WINNER, Regional 75 ANNIVERSARY & National EXIT Realty, 2017 & 2018 SPOTTING THE WESTERN 75e anniversaire du 436e Escadron de transport www.christinasellsquinte.com CHORUS FROG Rare artifact found and donated to Page 5 local museum NEW HONORARY COLONEL FOR 436 TRANSPORT SQUADRON 1-877-857-7726 613-962-7100 bellevillenissan.com By Makala Chapman elleville resident Jeremy BBraithwaite will be one of the rst to tell you that one man’s trash really is another man’s treasure. In this case, the treasure is a membership card to the caterpillar club, an artifact as rare as it is signi- cant in the aviation community. -

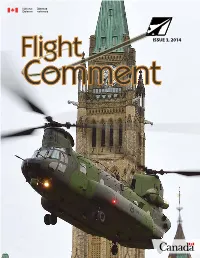

Issue 3, 2014

National Défense Defence nationale ISSUE 3, 2014 Cover – A CH147F Chinook helicopter prepares to land on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario on May 8, 2014 in preparation for the National Day of Honour to mark the end of our country’s military mission in Afghanistan. Visual Protection 8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 3, 2014 Always the Unexpected 18 Regular Columns Views on Flight Safety 2 Editor’s Corner 3 Good Shows 4 From the Flight Surgeon – Visual Protection 8 Maintenance in Focus – Indirect Effects on Flight Safety 10 Check Six – Air Frame Icing 12 On Track 14 From the Image Technician 17 Flight Safety Coin 21 Photo: Cplc Marc-Andre Gaudreault Gaudreault Marc-Andre Cplc Photo: From the Investigator – CH146485 Griffon 30 From the Investigator – SZ 2-33A 31 The Back Page- Directorate of Flight Safety (Ottawa) & 1 Canadian Air Division Flight Safety (Winnipeg) Organizational Chart 32 Dossiers Always the Unexpected 18 Flight Safety Coin 21 The Strength of an Idea 24 What’s Between Your Legs? 22 Lessons Learned Error on the Side of Safety 23 The Strength of an Idea 24 What’s That Smell? 26 Laser Guided Training 27 Crew Rest Limits 28 What’s That Smell? 26 DIRECTORATE OF THE CANADIAN FORCES Send submissions to: To contact DFS personnel on FLIGHT SAFETY FLIGHT SAFETY MAGAZINE an URGENT flight safety issue, National Defence Headquarters please call an investigator who is Director of Flight Safety Flight Comment is produced four times Directorate of Flight Safety available 24 hours a day at Colonel Steve Charpentier a year by the Directorate of Flight Safety. -

National Defence Team DEMOGRAPHICS ADVERTISE in 167 CANADIAN FORCES NEWSPAPERS LOCATED ACROSS CANADA Representing the Three CF Elements: Army, Air Force & Navy

MEDIA KIT REACH DND and the National Defence Team DEMOGRAPHICS ADVERTISE IN 167 CANADIAN FORCES NEWSPAPERS LOCATED ACROSS CANADA representing the three CF elements: Army, Air Force & Navy Canadian Forces COMMUNITY PROFILE Members of the CF and the Department of National Defence are powerful consumer groups. The National Defence Team Regular Force 64 000 Primary Reserve 34 500 Supplementary Reserve, Cadet Instructors Cadre and the Canadian Rangers 41 100 DND Public Servants 26 600 Total : 166 200 Regular Force DND 38% Public Servants 16% Supp. Reserve, Primary Cadet Inst. Reserve and Rangers 21% 25% *Data as of 2008 Statistics on the Canadian Forces members (Regular Force) Average age 35 Married or common-law 62% Married or common-law, with children 41% Reach this unique market Number of families 39 300 Average number of children 1.99 with only 1 point of contact! *Average income of officers $81 300 *Average income of non-commissioned members $55 600 * Based on average rank Captain/Corporal Stats are based on information provided by Director General Military Personnel and are current as of July 2008. CANADIAN FORCES NEWSPAPERS www.forcesadvertising.com OUR NEWSPAPERS Adsum The Aurora Borden Citizen Contact VALCARTIER GARRISON 14 WING GREENWOOD CFB BORDEN 8 WING TRENTON Québec, QC Greenwood, NS Borden, ON Trenton, ON The Courier Lookout North Bay Shield Petawawa Post 4 WING COLD LAKE CBF ESQUIMALT 22 WING NORTH BAY CFB PETAWAWA Cold Lake, AB Victoria, BC North Bay, ON Petawawa, ON The Post Gazette Servir The Shilo Stag Totem Times CFB GAGETOWN -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

Borden CAF Day & Air Show

2020 13 & 14 June 2020 Sponsorship Guide www.bordenairshow.ca A Modern Military on Display Each year, Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Borden trains 18,000 soldiers, sailors, and aviators to meet the challenges of modern security, warfare and peacekeeping.CF The Borden Canadian Armed Forces Day and Air Show is an opportunity to view military aircraft, vehicles and equipment up close and meet the men and women who use these tools to get the job done! CFB Borden is a part of your community CFB Borden actively participates and gives back to the community. GCWCC (Government of Canada Workplace Charitable Campaign) M.A.S.H. BASH Barrie Dragon Boat Festival Local Food Banks Terry Fox Foundation Seasonal Sharing Basket Hockey-thon for Soldier On Operation Red Nose Sponsorship Guide Base Borden Canadian Armed Forces Day & Air Show – 13 & 14 June 2020 Air show Audience demographics* Gender Age 20.00% Women 15.00% 43% Men 57% 10.00% 5.00% 0.00% 18 - 25 26 - 29 30 - 34 35 - 39 40 - 44 45 - 49 50 - 54 55 - 59 60+ Men Women Household Income Home Ownership 3% 35% 28% 30% 25% 69% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% Own Ren t Other Under $18 K $18 - 25 K $25 - 35 K $35 - 50 k $50 - 75 k $75 - 100 k $100 k + Education Level DistanceDistance travelled traveled to to attend attend an AirAir Show Some high Post grad High school school 18% grad15% 30.00% 2% 4 year degree Some college 20.00% 30% 35% 10.00% 0.00% Less than 17 km 17 - 32 km 32 - 64 km 64 - 96 km 96 - 128 km 128 - 160 km 160 + km Some high school High school grad Some college 4 year degree Post grad *2016 ICAS Spectator -

A Big Screen Finish

The WEDNESDAY, APRIL 30, 2014 • VOL. 24, NO.24 $1.25 Congratulations SOVA Class of KLONDIKE 2013-2014! SUN A big screen finish Dawson's Kit Hepburn accepts the Made In The Yukon award from Dawson City International Short Film Festival director Dan Sokolowski. Read the festival wrap on page 10. Photo by Dan Davidson. in this Issue Spring's here 3 1,200 km 8 A lifetime award 7 Don’t forget, The Ice Bridge is officially closed. Caribou Legs is on the move. There is more to come from the Mother’s Day TH Heritage Department. is May 11th! What to see and do in Dawson! 2 Letters 5 We need your glasses! 8 Bookends 17 Letters 3 A reunion banquet 5 Rangers' report 9 Business Directory & Job Board 19 Uffish Thoughts 4 More Waste Water issues 6 TV Guide 13-16 City Notices 20 P2 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 30, 2014 THE KLONDIKE SUN What to SEE AND DO in DAWSON now: SOVA SOVA STUDENT EXHIBITIONS: This free public service helps our readers find their way through the many activities all over town. Any small happening may need preparation and At the SOVA Gallery & ODD Gallery, from April planning, so let us know in good time! To join this listing contact the office at 25 to May 14. SOVA Gallery will be open to the public for viewing from 9 to 1 p.m. [email protected]. ADMIN OFFICE HOURS Events Monday to Thursday or by appointment. DARK STRANGERS TOUR: JUSTIN RUTLEDGE, OH SUSANNA & KIM LIBRARY HOURS : Monday to Thursday, 8:30 a.m. -

Joint Statement Calling for Sanctioning of Chinese and Hong Kong Officials and Protection for Hong Kongers at Risk of Political Persecution

Joint statement calling for sanctioning of Chinese and Hong Kong officials and protection for Hong Kongers at risk of political persecution We, the undersigned, call upon the Government of Canada to take action in light of the mass arrests and assault on civil rights following the unilateral imposition of the new National Security Law in Hong Kong. Many in Hong Kong fear they will face the same fate as the student protestors in Tiananmen Square, defenders’ lawyers, and millions of interned Uyghurs, Tibetans, and faith groups whose rights of free expression and worship are denied. We urge the Government of Canada to offer a “Safe Harbour Program” with an expedited process to grant protection and permanent residency status to Hong Kongers at risk of political persecution under the National Security Law, including international students and expatriate workers who have been involved in protest actions in Canada. Furthermore, Canada must invoke the Sergei Magnitsky Law to sanction Chinese and Hong Kong officials who instituted the National Security Law, as well as other acts violating human rights; and to ban them and their immediate family members from Canada and freeze their Canadian assets. Canada needs to work closely with international allies with shared values to institute a strong policy toward China. It is time for Canada to take meaningful action to show leadership on the world stage. Signatories: Civil society organizations Action Free Hong Kong Montreal Canada-Hong Kong Link Canada Tibet Committee Canadian Centre for Victims of -

Report on Transformation: a Leaner NDHQ?

• INDEPENDENT AND INFORMED • AUTONOME ET RENSEIGNÉ ON TRACK The Conference of Defence Associations Institute • L’Institut de la Conférence des Associations de la Défense Autumn 2011 • Volume 16, Number 3 Automne 2011 • Volume 16, Numéro 3 REPORT ON TRANSFORMATION: A leaner NDHQ? Afghanistan: Combat Mission Closure Reflecting on Remembrance ON TRACK VOLUME 16 NUMBER 3: AUTUMN / AUTOMNE 2011 PRESIDENT / PRÉSIDENT Dr. John Scott Cowan, BSc, MSc, PhD VICE PRESIDENT / VICE PRÉSIDENT Général (Ret’d) Raymond Henault, CMM, CD CDA INSTITUTE BOARD OF DIRECTORS LE CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE L’INSTITUT DE LA CAD EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / DIRECTEUR EXÉCUTIF Colonel (Ret) Alain M. Pellerin, OMM, CD, MA Admiral (Ret’d) John Anderson SECRETARY-TREASURER / SECRÉTAIRE TRÉSORIER Mr. Thomas d’Aquino Lieutenant-Colonel (Ret’d) Gordon D. Metcalfe, CD Dr. David Bercuson HONOURARY COUNSEL / AVOCAT-CONSEIL HONORAIRE Dr. Douglas Bland Mr. Robert T. Booth, QC, B Eng, LL B Colonel (Ret’d) Brett Boudreau DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH / Dr. Ian Brodie DIRECTEUR DE LA RECHERCHE Mr. Paul Chapin, MA Mr. Thomas S. Caldwell Mr. Mel Cappe PUBLIC AFFAIRS / RELATIONS PUBLIQUES Captain (Ret’d) Peter Forsberg, CD Mr. Jamie Carroll Dr. Jim Carruthers DEFENCE POLICY ANALYSTS / ANALYSTES DES POLITIQUES DE DÉFENSE Mr. Paul H. Chapin Ms. Meghan Spilka O’Keefe, MA Mr. Terry Colfer Mr. Arnav Manchanda, MA M. Jocelyn Coulon Mr. Dave Perry, MA Dr. John Scott Cowan PROJECT OFFICER / AGENT DE PROJET Mr. Dan Donovan Mr. Paul Hillier, MA Lieutenant-général (Ret) Richard Evraire Conference of Defence Associations Institute Honourary Lieutenant-Colonel Justin Fogarty 151 Slater Street, Suite 412A Ottawa ON K1P 5H3 Colonel, The Hon. -

Making Positive Impacts ISSUE 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 QMS CONNECTIONS ISSUE 4 SEPTEMBER 2016

Making Positive Impacts ISSUE 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 QMS CONNECTIONS ISSUE 4 SEPTEMBER 2016 Back from the Brink IN THIS ISSUE The Wonder Wagon An Idea Takes Root 33 STUDENTS 2016 QMS Grad Class 2016GRAD CLASS Which CANADIAN UNIVERSITY WAS MOST POPULAR for the Class of 2016 to attend? UVIC THE UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA SENIOR SCHOOL Lifers’ Awards This year, four students received a Lifer’s Award for attending QMS for six or more years: Sydney McCrae, Isabelle Pumple, Lalaine Gower and Christine Coels 83 ACCEPTANCES to CANADIAN 11 Universities/Colleges ACCEPTANCES to 13 UK University/Colleges ACCEPTANCES to 1 AMERICAN ACCEPTANCE Universities/Colleges to an ASIAN UNIVERSITY Top programs of study Which a tie between Psychology (4) US UNIVERSITY and the Fine Arts (4) was MOST POPULAR for the Class of 2016 to attend? FIT FASHION INSTITUTE OF 108 TECHNOLOGY POST-SECONDARY ACCEPTANCES to educational institutions around the world Head’s Message BY WILMA JAMIESON Currently I am reading Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World. Described as one of this generation’s most compelling and provocative thought leaders, author Adam Grant addresses the challenge of how do we improve the world around us. in open and mutually beneficial ways, sharing knowledge, offering viewpoints and differing opinions. We invest time and energy in not what is, but what can be, striving to know more through inquiry and research. We get to the root of an issue, understanding contributing factors and arriving at new solutions. We provide inspiration to others; the overflow of positive energy within our community is uplifting, enriching the lives of others. -

Children: the Silenced Citizens

Children: The Silenced Citizens EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF CANADA’S INTERNATIONAL OBLIGATIONS WITH RESPECT TO THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN Final Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights The Honourable Raynell Andreychuk Chair The Honourable Joan Fraser Deputy Chair April 2007 Ce document est disponible en français. This report and the Committee’s proceedings are available online at www.senate-senat.ca/rights-droits.asp Hard copies of this document are available by contacting the Senate Committees Directorate at (613) 990-0088 or by email at [email protected] Membership Membership The Honourable Raynell Andreychuk, Chair The Honourable Joan Fraser, Deputy Chair and The Honourable Senators: Romeo Dallaire *Céline Hervieux-Payette, P.C. (or Claudette Tardif) Mobina S.B. Jaffer Noël A. Kinsella *Marjory LeBreton, P.C. (or Gerald Comeau) Sandra M. Lovelace Nicholas Jim Munson Nancy Ruth Vivienne Poy *Ex-officio members In addition, the Honourable Senators Jack Austin, George Baker, P.C., Sharon Carstairs, P.C., Maria Chaput, Ione Christensen, Ethel M. Cochrane, Marisa Ferretti Barth, Elizabeth Hubley, Laurier LaPierre, Rose-Marie Losier-Cool, Terry Mercer, Pana Merchant, Grant Mitchell, Donald H. Oliver, Landon Pearson, Lucie Pépin, Robert W. Peterson, Marie-P. Poulin (Charette), William Rompkey, P.C., Terrance R. Stratton and Rod A. Zimmer were members of the Committee at various times during this study or participated in its work. Staff from the Parliamentary Information and Research Service of the Library of Parliament: