Report on Democracy in Spain 2008 the Stratgey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Legado De La Edad Media: El Régimen Señorial En El Reino De Jaén (Siglos XV-XVIII)

El legado de la Edad Media: el régimen señorial en el Reino de Jaén (siglos XV-XVIII) No pretende el presente trabajo exponer de modo exhaustivo to- das y cada una de las vicisitudes por las que atravesaron los seño- ríos y las familias que los detentaron en el Reino de Jaén, durante el largo período de cuatro siglos que nos ocupa. Más bien se trata de presentar el resultado de las investigaciones llevadas a cabo tanto por los historiadores preocupados por la historia giennense en este campo como por mí mismo. Para ello es de primordial interés establecer una primera evalua- ción de los pueblos que estuvieron situados bajo la órbita señorial desde el momento de la «Reconquista» del Reino hasta el siglo pa- sado, labor completa que, obviamente, desborda las pretensiones de cualquier investigador individual. No se agota, sin embargo, el estudio del régimen señorial en es- tos aspectos locales; este sistema de concebir la sociedad, que ocupa las Edades Media y Moderna, envuelve y caracteriza todas sus es- tructuras, hasta el extremo de que, incluso, los concejos realengos acaban siendo dominados por la nobleza local, que procura consti- tuir o ampliar su patrimonio a costa de los bienes de estos concejos. No obstante, tampoco esto debe extrañarnos, toda vez que el pro- pio concejo de realengo actúa con respecto a sus aldeas como un señor más, exigiéndoles la prestación de pleito-homenaje y la contri- bución de cantidades por diversos conceptos, así como sometiéndo- las a la directa jurisdicción de sus justicias. Podríamos definir el régimen señorial, siguiendo al profesor don Eduardo de Hinojosa, como «el conjunto de las relaciones de depen- dencia de unos individuos respecto de otros, ya por razón de la 798 Pedro A, Porras Arboledas persona, ya de la tierra [..], y la organización económica, social y política derivada de aquellas relaciones»’. -

Gibson CV 2020

Mara Gibson maragibson.com 5652 Burgundy Ave [email protected] Baton Rouge, LA 70806 (913) 957-6876: cell Education 1996--2001 Ph.D. Music Composition, State University of New York at Buffalo; Buffalo, NY Committee Members: David Felder, Martha Hyde, Erik Oña, Michael Long; Outside Reader: Stephen Jaffe, Duke University; Dissertation: mirar 1990--1994 Bachelor of Arts, Music Composition and Piano Performance, Bennington College; Bennington, VT Positions 2017—present Louisiana State University, Associate Professor of Composition (starting 2018) Visiting Assistant Professor: Composition (2017-18), Composition Forum, Laptop Orchestra, Constantinides New Music Ensemble, Orchestration (CxC certified), Contemporary Musical Practices PhD Committees: William Montgomery (chair), Landon Viator, Shane Courville, Christopher McCardle; MM Committee: Austin Franklin; Honors Thesis Committee: Hollyn Slykhuis, Mikeila McQueston (National Board of Sigma Phi Chapter Scholastic Award, LSU Presser Award) 2004--2017 Conservatory of Music and Dance, University of Missouri-Kansas City Associate Teaching Professor (2013- present), Instructor (2004-2013): Composition (133-433), Creative Strategies for Collaboration, Composition Forum, Ensembles for Composers, MUSE, graduate faculty (committee member), Musicianship IV, Composition Coordinator for Undergraduate Recruitment (2016), supervise all teaching artists for Conservatory in the Schools, Composition Workshop founder and director. Recent DMA committees: Dylan Baker, Tatev Amiryan, AMao Wang, MM Committees: -

Claimed Studios Self Reliance Music 779

I / * A~V &-2'5:~J~)0 BART CLAHI I.t PT. BT I5'HER "'XEAXBKRS A%9 . AFi&Lkz.TKB 'GMIG'GCIKXIKS 'I . K IUOF IH I tt J It, I I" I, I ,I I I 681 P U B L I S H E R P1NK FLOWER MUS1C PINK FOLDER MUSIC PUBLISH1NG PINK GARDENIA MUSIC PINK HAT MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PINK 1NK MUSIC PINK 1S MELON PUBL1SHING PINK LAVA PINK LION MUSIC PINK NOTES MUS1C PUBLISHING PINK PANNA MUSIC PUBLISHING P1NK PANTHER MUSIC PINK PASSION MUZICK PINK PEN PUBLISHZNG PINK PET MUSIC PINK PLANET PINK POCKETS PUBLISHING PINK RAMBLER MUSIC PINK REVOLVER PINK ROCK PINK SAFFIRE MUSIC PINK SHOES PRODUCTIONS PINK SLIP PUBLISHING PINK SOUNDS MUSIC PINK SUEDE MUSIC PINK SUGAR PINK TENNiS SHOES PRODUCTIONS PiNK TOWEL MUSIC PINK TOWER MUSIC PINK TRAX PINKARD AND PZNKARD MUSIC PINKER TONES PINKKITTI PUBLISH1NG PINKKNEE PUBLISH1NG COMPANY PINKY AND THE BRI MUSIC PINKY FOR THE MINGE PINKY TOES MUSIC P1NKY UNDERGROUND PINKYS PLAYHOUSE PZNN PEAT PRODUCTIONS PINNA PUBLISHING PINNACLE HDUSE PUBLISHING PINOT AURORA PINPOINT HITS PINS AND NEEDLES 1N COGNITO PINSPOTTER MUSIC ZNC PZNSTR1PE CRAWDADDY MUSIC PINT PUBLISHING PINTCH HARD PUBLISHING PINTERNET PUBLZSH1NG P1NTOLOGY PUBLISHING PZO MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PION PIONEER ARTISTS MUSIC P10TR BAL MUSIC PIOUS PUBLISHING PIP'S PUBLISHING PIPCOE MUSIC PIPE DREAMER PUBLISHING PIPE MANIC P1PE MUSIC INTERNATIONAL PIPE OF LIFE PUBLISHING P1PE PICTURES PUBLISHING 882 P U B L I S H E R PIPERMAN PUBLISHING P1PEY MIPEY PUBLISHING CO PIPFIRD MUSIC PIPIN HOT PIRANA NIGAHS MUSIC PIRANAHS ON WAX PIRANHA NOSE PUBL1SHING P1RATA MUSIC PIRHANA GIRL PRODUCTIONS PIRiN -

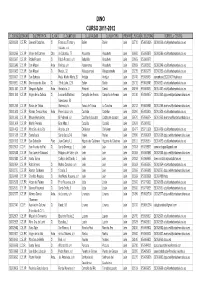

Programa Dino Jaen

DINO CURSO 2011-2012 C_CODIGOS_DENOMINA D_ESPECIFICA S_VIA D_DOMICILIO D_LOCALIDAD D_MUNICIPIO D_PROVINCIAC_POSTALN_TELEFONO CORREO_e CENTRO 23000039 C.E.PR. General Castaños C/ Francisco Tomás y Bailén Bailén Jaén 23710 953609926 [email protected] Valiente, s/n 23000283 C.E.I.P. Virgen del Carmen Ctra. de Córdoba, 77 Alcaudete Alcaudete Jaén 23660 953366878 [email protected] 23000337 C.E.I.P. Pablo Picasso C/ Pablo Picasso, s/n. Bobadilla Alcaudete Jaén 23669 953366970 23000349 C.E.I.P. San Miguel Avda. Delicias s/n Noguerones Alcaudete Jaén 23669 953366123 [email protected] 23000362 C.E.I.P. San Miguel C/ Mesón, 32 Aldeaquemada Aldeaquemada Jaén 23215 953609750 [email protected] 23000507 C.E.I.P. San Eufrasio Rvda. Madre Marta, 30 Andújar Andújar Jaén 23740 953539524 [email protected] 23000921 C.E.PR. Diecinueve de Julio C/ 19 de Julio, 123 Bailén Bailén Jaén 23710 953609545 [email protected] 23001147 C.E.I.P. Gregorio Aguilar Avda. Andalucía, 17 Arbuniel Cambil Jaén 23193 953366454 [email protected] 23001160 C.E.I.P. Virgen de la Cabeza C/ Leonardo Martínez Campillo de Arenas Campillo de Arenas Jaén 23130 953366957 [email protected] Valenzuela, 54 23001299 C.E.I.P. Navas de Tolosa Alamos,s/n. Navas de Tolosa La Carolina Jaén 23212 953609949 [email protected] 23001329 C.E.I.P. Román Crespo Hoyo Avda. Pepe López, s/n Castellar Castellar Jaén 23260 953409904 [email protected] 23001330 C.E.I.P. Miguel Hernández El Pedregal, s/n Castillo de Locubín Castillo de Locubín Jaén 23670 953599554 [email protected] 23001366 C.E.I.P. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science Civilian Control of the Military in Portugal and Spain: a Policy Instruments Approach José Javier Olivas Osuna A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, March 2012 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. e copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. is thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of words. Abstract Despite their economic, political and cultural similarities, Portugal and Spain experienced dif- ferent trajectories of civil-military relations during the twentieth century. After having handed power over to a civilian dictator, Salazar, the Portuguese military eventually caused the down- fall of his authoritarian Estado Novo regime and led the transition to democracy. In contrast, in Spain the military, which had helped Franco to defeat the Republic in remained loyal to the dictatorship’s principles and, after his death, obstructed the democratisation process. is research sheds light on these different patterns by comparing the policy instruments that governments used to control the military throughout Portuguese and Spanish dictatorships and transitions to democracy. First, it applies Christopher Hood’s () ‘’ (nodality, authority, treasure and organisation) framework for the study of tools of government in order to identify trajectories and establish comparisons across time and countries. -

Catalogue a ‐ Z

Catalogue A ‐ Z A ? MARK AND MYSTERIANS "Same" LP CAMEO 1966 € 60 (US Garage‐Original Canada Pressing VG++++/VG+) 007 & SCENE " Landscapes" LP Detour € 12 (UK mod‐beat ' 70/ ' 80) 1‐2‐5 “Same” LP Misty lane € 13 (Garage punk dall’Olanda) 13th FLOOR ELEVATORS "Easter every Where" CD Spalax € 15,00 ('60 US Psych) 13th FLOOR ELEVATORS "Graeckle Debacle" CD Spalax € 15,00 ('60 US Psych) 13th FLOOR ELEVATORS "The Psychedelic Sound Of…" CD Spalax € 15,00 ('60 US Psych) 13th FLOOR ELEVATORS "Unlock the Secret" CD Spalx € 15,00 ('66 US Psych) 20/20 "Giving It All" 7" LINE 1979 € 15 (US Power Pop) 27 DEVILS JOKING "The Sucking Effect" LP RAVE 1991 € 10 (US Garage VG/M‐) 3 NORMAL BEATLES "We Name Is Justice" DLP BUBACK € 23 (Beat from Germany) 39 CLOCKS "Cold Steel To The Heart " LP WHAT'S SO FUNNY ABOUT 1985 € 35 (Psychedelic Wave from Germany) 39 CLOCKS "Subnarcotic" LP WHAT'S SO FUNNY ABOUT 1982 € 35 (Psychedelic Wave from Germany 1988 Reissue) 39 CLOCKS "The Original Psycho Beat" LP WHAT'S SO FUNNY ABOUT 1993 € 20 (Psychedelic Wave from Germany) 3D INVISIBLES "Robot Monster" 7" NEUROTIC BOP 1994 € 5 (US Punk Rock) 3D INVISIBLES "They Won't StayDead" LP NEUROTIC BOP 1989 € 15 (US Punk Rock) 440’S “Gas Grass Or As” 7” Rockin’ Bones € 5 (US Punk) 5 LES “Littering..” 7” HAGCLAND 198? € 5 (Power Pop dal Belgio M‐/M‐) 5.6.7.8.'S "Can't Help It !" CD AUGOGO € 14 (Japan Garage i 7"M‐/M) 5.6.7.8's "Sho‐Jo‐Ji" 7" THIRD MAN € 9 (Garage Punk from Tokyo) 60 FT DOLLS "Afterglow" 7" DOLENT € 3 (Promo Only) 64 SPIDERS "Potty Swat" 7" REGAL SELECT 1989 € 17 (US Punk M‐/M‐) 68 COMEBACK "Do The Rub" 7" BAG OF HAMMERS 1994 € 7 (US Punk Blues) 68 COMEBACK "Flip,Flop,& Fly" 7" GET HIP 1994 € 13 (US Punk Blues) 68 COMEBACK "Great Million Sellers" 7" 1+2 1994 € 8 (US Punk Blues) 68 COMEBACK "High Scool Confidential" 7" PCP I. -

Wwaaagggooonnn Wwhhheeeeeell

WWAAGGOONN WWHHEEEELL RREECCOORRDDSS Music for Education & Recreation Rhythms • Folk • Movement YYoouurr CChhiillddrreenn’’ss aanndd TTeeaacchheerr’’ss SSppeecciiaalliisstt ffoorr MusicMusic andand DanceDance VS 067 Brenda Colgate WWAAGGOONN WWHHEEEELL RREECCOORRDDSS 16812 Pembrook Lane • Huntington Beach, CA 92649 Phone or Fax: 714-846-8169 • www.wagonwheelrecords.net TTaabbllee ooff CCoonntteennttss Music for Little People . .3 Holiday Music . .20 Quiet Time . .3 Kid’s Fun Music . .21-22 Expression . .3 Kid’s Dance/Party Music . .23 Fun For Little People . .4-5 Dance/Party Music . .24-26 Manipulatives & Games . .6-8 Sports . .26 Jump-Rope Skills . .6 Island Music . .26 Streamers/Scarves/Balls . .6 Dance Videos & Music - Christy Lane . .27-29 Games & Skills . .7 Country Dancing Bean Bag . .7 . .30 Parachute Activities . .8 Square Dancing . .31-33 Seated Exercises . .8 Christy Lane’s . .31 Aerobic/Fitness/Movement . .9 Everyone’s Square Dances . .32 Square Dancing for All Ages . .32 Fitness/Movement Activities . .10-11 Fundamentals of Square Dancing Instructional Series . .33 Lee Campbell-Towell . .10 Square Dance Party For The New Dancer Series . .33 Physical Education . .12-13 Folk Dancing . .34-37 Dynamic Program . .12 Rhythmically Moving Series . .34 Spark Program . .13 Beginning Folk Dances . .35 Music & Movement . .14-15 We Dance Series . .35 Rhythm & Movement . .16-18 Young People’s Folk Dances . .36 Rhythm Sticks . .16 Christy Lane . .37 Tinikling . .16 Multicultural Songs & Greg and Steve . .18 Dances . .38-39 Rhythm, Movement -

Municipios De La Provincia De Jaén

E JAEN NO SE PRESTA Sólo puede consultarse dentro de la sala de lectura O -era- o /¿• .%c/-<K ^/"""^fc Sierra, 180/ P.Yeímo £ c / *> /ítASAGRA 38 ©Caloría Qtiesaíía.i J üurúá Salera JAÉN O tai «<x- cU ffc tUíií. • .{AtBMTO MARTI». * * * Cimite di-^ptwiivcta, • .E01T0»-»ARCEL0I1A. G EsealcL, cU i: ISSO, 000 Gi't-titila*. • , CJ c PROVINCIA DE JAÉN Se halla situada en la parte alta de de Granada, y distrito Universitario de Andalucía, confinando por el N. con la esta última. provincia de Ciudad Real; al E. con las Orográfica é hidrográficamente consi• de Albacete y Granada; al S. esta última derada tiene mucha importancia esta pro• y al O. la de Córdoba. Viene compren• vincia, ya que su territorio en el extremo dida entre los 37o 28' y 38o 33' de lati• NE., mediante la sierra de Segura, forma tud N. y 00 35' de longitud O. y i0 i5' la divisoria entre las vertientes del río de al E. del meridiano de Madrid. este nombre, comprendido en la cuenca Su extensión superficial es de 13,480 Mediterránea, y el Guadalquivir en la kilómetros cuadrados, con una población Atlántica. La sierra Morena en sus estri• de 474,490 habitantes. baciones orientales, la separa de la pro• Comprende los 13 partidos judiciales vincia de Ciudad Real, figurando ade• de Alcalá la Real, Andújar, Baeza, La más entre sus montes principales la sierra Carolina, Cazorla, Huelma, Jaén, Lina• de Cazorla y sierra de Pozo-Alcón, entre res, Mancha Real, Martos, Orcera, Ube- las cuales tiene sus fuentes el Guadalqui• da y Villacarrillo, en la Audiencia pro• vir; la loma de Ubeda en el partido de vincial de Jaén y Territorial de Granada; este nombre; la de Chiclana, á la derecha segundo cuerpo de Ejército; diócesis en del Guadalimar, en el partido de Villa- la Capital, sufragánea del Arzobispado carrillo; la de Magina, de 2,170 metros de altitud, en el confín del de Mancha Real legumbres y pastos y muy especialmente y Huelma; Alto Coloma en este último y los productos minerales de plomo en Li• el monte Jabalcur al O. -

The Role of Smart Power in U.S.-Spain Relations, 1969-1986

THE ROLE OF SMART POWER IN U.S.-SPAIN RELATIONS, 1969-1986 By DAVID A. JUSTICE Bachelor of Arts in History Athens State University Athens, Alabama 2012 Master of Arts in History University of North Alabama Florence, Alabama 2014 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 2020 THE ROLE OF SMART POWER IN U.S.-SPAIN RELATIONS, 1969-1986 Dissertation Approved: Dr. Laura Belmonte Dissertation Adviser Dr. Douglas Miller Dr. Matthew Schauer Dr. Isabel Álvarez-Sancho ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation, this labor of love, would not be complete if it were not for a number of people. First, I would like to thank my dissertation committee of brilliant scholars. My advisor Laura Belmonte was integral in shaping this work and myself as an academic. Since my arrival at Oklahoma State, Dr. B has crafted me into the scholar that I am now. Her tireless encouragement, editing of multiple drafts, and support of this ever evolving project will always be appreciated. She also provided me with numerous laughs from the presidential pups, Willy and James. Doug Miller has championed my work since we began working together, and his candor and unconditional support was vital to finishing. Also, our discussions of Major League Baseball were much needed during coursework. Matt Schauer’s mentorship was integral to my time at Oklahoma State. The continuous laughter and support during meetings, along with discussions of classic films, were vital to my time at Oklahoma State. -

Authorized Catalogs - United States

Authorized Catalogs - United States Miché-Whiting, Danielle Emma "C" Vic Music @Canvas Music +2DB 1 Of 4 Prod. 10 Free Trees Music 10 Free Trees Music (Admin. by Word Music Group, 1000 lbs of People Publishing 1000 Pushups, LLC Inc obo WB Music Corp) 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers 10000 Fathers SESAC Designee 10000 MINUTES 1012 Rosedale Music 10KF Publishing 11! Music 12 Gate Recordings LLC 121 Music 121 Music 12Stone Worship 1600 Publishing 17th Avenue Music 19 Entertainment 19 Tunes 1978 Music 1978 Music 1DA Music 2 Acre Lot 2 Dada Music 2 Hour Songs 2 Letit Music 2 Right Feet 2035 Music 21 Cent Hymns 21 DAYS 21 Songs 216 Music 220 Digital Music 2218 Music 24 Fret 243 Music 247 Worship Music 24DLB Publishing 27:4 Worship Publishing 288 Music 29:11 Church Productions 29:Eleven Music 2GZ Publishing 2Klean Music 2nd Law Music 2nd Law Music 2PM Music 2Surrender 2Surrender 2Ten 3 Leaves 3 Little Bugs 360 Music Works 365 Worship Resources 3JCord Music 3RD WAVE MUSIC 4 Heartstrings Music 40 Psalms Music 442 Music 4468 Productions 45 Degrees Music 4552 Entertainment Street 48 Flex 4th Son Music 4th teepee on the right music 5 Acre Publishing 50 Miles 50 States Music 586Beats 59 Cadillac Music 603 Publishing 66 Ford Songs 68 Guns 68 Guns 6th Generation Music 716 Music Publishing 7189 Music Publishing 7Core Publishing 7FT Songs 814 Stops Today 814 Stops Today 814 Today Publishing 815 Stops Today 816 Stops Today 817 Stops Today 818 Stops Today 819 Stops Today 833 Songs 84Media 88 Key Flow Music 9t One Songs A & C Black (Publishers) Ltd A Beautiful Liturgy Music A Few Good Tunes A J Not Y Publishing A Little Good News Music A Little More Good News Music A Mighty Poythress A New Song For A New Day Music A New Test Catalog A Pirates Life For Me Music A Popular Muse A Sofa And A Chair Music A Thousand Hills Music, LLC A&A Production Studios A. -

Turismo Musical Un Análisis De La Oferta Y Demanda Local De Viajes a Festivales Internacionales De Música Electrónica

Tesis de Grado Licenciatura en Turismo Turismo Musical Un análisis de la oferta y demanda local de viajes a festivales internacionales de música electrónica. Florencia Gelosi Legajo N° 84.280/5 [email protected] Director Mg. Aníbal Cueto Co-Director Prof. Martín Coelho 29 de noviembre de 2019 La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina AGRADECIMIENTOS A mi familia, principalmente a mi papá, que sin su apoyo mi paso por la facultad hubiera sido muy diferente. A mis amigos de toda la vida, y aquellos que conocí dentro de la facultad quienes hicieron leve y hasta divertido mi tránsito por este proceso. A mi pareja, Leandro, por acompañarme y prepararme tecitos en mis momentos de estudio y redacción. A los profesores de la Licenciatura en Turismo de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la UNLP por su dedicación y capacidad de transmitir la pasión por la profesión. A la comunidad de la Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, que me ha abierto sus puertas desde el primer día, y donde siempre me siento bienvenida a participar y compartir iniciativas. A mi director de Tesis, Aníbal Cueto, por su asesoramiento y orientación en el desarrollo de mi investigación. A mi Co-director y querido amigo, Martín Coelho, para quien no existe medida de agradecimiento suficiente por la dedicación, paciencia, buena onda, predisposición, y permanente acompañamiento que tuvo para conmigo durante este proceso. Y finalmente, a aquellas personas entrevistadas en mi trabajo y a todos los amantes de la música electrónica que tan amablemente colaboraron con mi investigación. ¡A todos ellos, GRACIAS! 1 ÍNDICE RESUMEN .................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................ -

The Use of Twitter by the Main Candidates in the General Election Campaigns in Spain: 2011 and 2015

The use of Twitter by the main candidates in the general election campaigns in Spain: 2011 and 2015. Is there a digital and generational gap? El uso de Twitter por parte de los principales candidatos en las campañas electorales para las elecciones generales españolas: 2011 y 2015. ¿Brecha digital y generacional? Laura Cervi. She is Associate Professor at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in the Faculty of Communi- cation Sciences, and she also has a Doctorate in Political Science from the Universita di Pavia, Italy, based on research entitled Nazionalismo e mercato elettorale: il caso catalano (“Nationalism and the electoral market: the Catalonian case”), in the area of Political Communication. Finally, Laura Cervi earned her Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from the Universita di Pavia, Italy with work and research conducted in the United States. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-0376-0609 Núria Roca Trenchs. She is currently studying a PhD in communication and journalism at the Universitat Autò- noma de Barcelona. She has an Official Master’s Degree in Research in Communication and Journalism from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona as well. Roca holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Audiovisual Communication from the Open University of Catalonia, a Postgraduate Degree in Digital Journalism from the same University, and a Bachelor’s Degree in Philosophy from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, España [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-9389-5098