Spatial Ecology of Nassau Grouper at Home Reef Sites: Using Acoustic Telemetry to Track a Large, Long-Lived Epinephelid Across Multiple Years (2005−2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combined!Effects!In!Europe's!Seas!

OCP/EEA/NSS/18/002.ETC/ICM!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!ETC/ICM!Technical!Report!4/2019! Multiple!pressures!and!their! combined!effects!in!Europe’s!seas! Prepared!by!/!compiled!by:!! Samuli!Korpinen,!Katja!Klančnik! Authors:!! Samuli Korpinen & Katja Klančnik (editors), Monika Peterlin, Marco Nurmi, Leena Laamanen, Gašper Zupančič, Ciarán Murray, Therese Harvey, Jesper H Andersen, Argyro Zenetos, Ulf Stein, Leonardo Tunesi, Katrina Abhold, GerJan Piet, Emilie Kallenbach, Sabrina Agnesi, Bas Bolman, David Vaughan, Johnny Reker & Eva Royo Gelabert ETC/ICM'Consortium'Partners:'' Helmholtz!Centre!for!Environmental!Research!(UFZ),!Fundación!AZTI,!Czech!Environmental! Information!Agency!(CENIA),!Ioannis!Zacharof&!Associates!Llp!Hydromon!Consulting! Engineers!(CoHI(Hydromon)),!Stichting!Deltares,!Ecologic!Institute,!International!Council!for! the!Exploration!of!the!Sea!(ICES),!Italian!National!Institute!for!Environmental!Protection!and! Research!(ISPRA),!Joint!Nature!Conservation!Committee!Support!Co!(JNCC),!Middle!East! Technical!University!(METU),!Norsk!Institutt!for!Vannforskning!(NIVA),!Finnish!Environment! Institute!(SYKE),!Thematic!Center!for!Water!Research,!Studies!and!Projects!development!! (TC!Vode),!Federal!Environment!Agency!(UBA),!University!Duisburg.Essen!(UDE)! ! ! ! Cover'photo! ©!Tihomir!Makovec,!Marine!biology!station!Piran,!Slovenia! ' Layout! F&U!confirm,!Leipzig! ! Legal'notice' The!contents!of!this!publication!do!not!necessarily!reflect!the!official!opinions!of!the!European!Commission!or!other!institutions! -

Multiple!Pressures!And!Their! Combined!Effects!In!Europe's!Seas!

OCP/EEA/NSS/18/002.ETC/ICM!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!ETC/ICM!Technical!Report!4/2019! Multiple!pressures!and!their! combined!effects!in!Europe’s!seas! Prepared!by!/!compiled!by:!! Samuli!Korpinen,!Katja!Klančnik! Authors:!! Monika Peterlin, Marco Nurmi, Leena Laamanen, Gašper Zupančič, Andreja Popit, Ciarán Murray, Therese Harvey, Jesper H Andersen, Argyro Zenetos, Ulf Stein, Leonardo Tunesi, Katrina Abhold, GerJan Piet, Emilie Kallenbach, Sabrina Agnesi, Bas Bolman, David Vaughan, Johnny Reker & Eva Royo Gelabert ETC/ICM'Consortium'Partners:'' Helmholtz!Centre!for!Environmental!Research!(UFZ),!Fundación!AZTI,!Czech!Environmental! Information!Agency!(CENIA),!Ioannis!Zacharof&!Associates!Llp!Hydromon!Consulting! Engineers!(CoHI(Hydromon)),!Stichting!Deltares,!Ecologic!Institute,!International!Council!for! the!Exploration!of!the!Sea!(ICES),!Italian!National!Institute!for!Environmental!Protection!and! Research!(ISPRA),!Joint!Nature!Conservation!Committee!Support!Co!(JNCC),!Middle!East! Technical!University!(METU),!Norsk!Institutt!for!Vannforskning!(NIVA),!Finnish!Environment! Institute!(SYKE),!Thematic!Center!for!Water!Research,!Studies!and!Projects!development!! (TC!Vode),!Federal!Environment!Agency!(UBA),!University!Duisburg.Essen!(UDE)! ! ! ! Cover'photo! ©!Tihomir!Makovec,!Marine!biology!station!Piran,!Slovenia! ' Layout! F&U!confirm,!Leipzig! ! Legal'notice' The!contents!of!this!publication!do!not!necessarily!reflect!the!official!opinions!of!the!European!Commission!or!other!institutions! of!the!European!Union.!Neither!the!European!Environment!Agency,!the!European!Topic!Centre!on!Inland,!Coastal!and!Marine! -

Epinephelus Drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / None

click for previous page 1340 Bony Fishes Epinephelus drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / None. FAO names: En - Speckled hind; Fr - Mérou grivelé; Sp - Mero pintaroja. Diagnostic characters: Body depth subequal to head length, 2.4 to 2.6 times in standard length (for fish 20 to 43 cm standard length). Nostrils subequal; preopercle rounded, evenly serrate. Gill rakers on first arch 9 or 10 on upper limb, 17 or 18 on lower limb, total 26 to 28. Dorsal fin with 11 spines and 15 or 16 soft rays, the membrane incised between the anterior spines; anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays; caudal fin trun- cate or slightly emarginate, the corners acute; pectoral-fin rays 18. Scales strongly ctenoid, about 125 lateral-scale series; lateral-line scales 72 to 76. Colour: adults (larger than 33 cm) dark reddish brown, densely covered with small pearly white spots; juveniles (less than 20 cm) bright yellow, covered with small bluish white spots. Size: Maximum about 110 cm; maximum weight 30 kg. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Adults inhabit offshore rocky bottoms in depths of 25 to 183 m but are most common between 60 and 120 m.Females mature at 4 or 5 years of age (total length 45 to 60 cm).Spawning oc- curs from July to September, and a large female may produce up to 2 million eggs at 1 spawning. Back-calculated total lengths for fish aged 1 to 15 years are 19, 32, 41, 48, 53, 57, 61, 65, 68, 71, 74, 77, 81, 84, and 86 cm; the maximum age attained is at least 25 years, and the largest specimen measured was 110 cm. -

Diet Composition of Juvenile Black Grouper (Mycteroperca Bonaci) from Coastal Nursery Areas of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 77(3): 441–452, 2005 NOTE DIET COMPOSITION OF JUVENILE BLACK GROUPER (MYCTEROPERCA BONACI) FROM COASTAL NURSERY AREAS OF THE YUCATÁN PENINSULA, MEXICO Thierry Brulé, Enrique Puerto-Novelo, Esperanza Pérez-Díaz, and Ximena Renán-Galindo Groupers (Epinephelinae, Epinephelini) are top-level predators that influence the trophic web of coral reef ecosystems (Parrish, 1987; Heemstra and Randall, 1993; Sluka et al., 2001). They are demersal mesocarnivores and stalk and ambush preda- tors that sit and wait for larger moving prey such as fish and mobile invertebrates (Cailliet et al., 1986). Groupers contribute to the ecological balance of complex tropi- cal hard-bottom communities (Sluka et al., 1994), and thus large changes in their populations may significantly alter other community components (Parrish, 1987). The black grouper (Mycteroperca bonaci Poey, 1860) is an important commercial and recreational fin fish resource in the western Atlantic region (Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). The southern Gulf of Mexico grouper fishery is currently considered to be deteriorated and M. bonaci, along with red grouper (Epinephelus morio Valenciennes, 1828) and gag (Mycteroperca microlepis Goode and Bean, 1880), is one of the most heavily exploited fish species in this region (Co- lás-Marrufo et al., 1998; SEMARNAP, 2000). Currently, M. bonaci is considered a threatened species (Morris et al., 2000; IUCN, 2003) and has been classified as vul- nerable in U.S. waters because male biomass in the Atlantic dropped from 20% in 1982 to 6% in 1995 (Musick et al., 2000). The black grouper is usually found on irregular bottoms such as coral reefs, drop- off walls, and rocky ledges, at depths from 10 to 100 m (Roe, 1977; Manooch and Mason, 1987; Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). -

V a Tion & Management of Reef Fish Sp a Wning Aggrega Tions

handbook CONSERVATION & MANAGEMENT OF REEF FISH SPAWNING AGGREGATIONS A Handbook for the Conservation & Management of Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations © Seapics.com Without the Land and the Sea, and their Bounties, the People and their Traditional Ways would be Poor and without Cultural Identity Fijian Proverb Why a Handbook? 1 What are Spawning Aggregations? 2 How to Identify Spawning Aggregations 2 Species that Aggregate to Spawn 2 Contents Places Where Aggregations Form 9 Concern for Spawning Aggregations 10 Importance for Fish and Fishermen 10 Trends in Exploited Aggregations 12 Managing & Conserving Spawning Aggregations 13 Research and Monitoring 13 Management Options 15 What is SCRFA? 16 How can SCRFA Help? 16 SCRFA Work to Date 17 Useful References 18 SCRFA Board of Directors 20 Since 2000, scientists, fishery managers, conservationists and politicians have become increasingly aware, not only that many commercially important coral reef fish species aggregate to spawn (reproduce) but also that these important reproductive gatherings are particularly susceptible to fishing. In extreme cases, when fishing pressure is high, aggregations can dwindle and even cease to form, sometimes within just a few years. Whether or not they will recover and what the long-term effects on the fish population(s) might be of such declines are not yet known. We do know, however, that healthy aggregations tend to be associated with healthy fisheries. It is, therefore, important to understand and better protect this critical part of the life cycle of aggregating species to ensure that they continue to yield food and support livelihoods. Why a Handbook? As fishing technology improved in the second half of the twentieth century, engines came to replace sails and oars, the cash economy developed rapidly, and human populations and demand for seafood grew, the pressures on reef fishes for food, and especially for money, increased enormously. -

Nassau Grouper

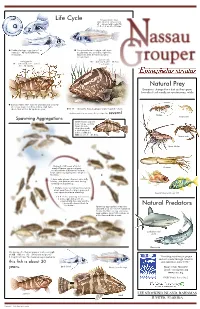

Life Cycle Pelagic juvenile stage (Late larval to early juvenile) 25 ‒ 30 mm total length (TL) (1.0 ‒ 1.2 in) 35 ‒ 50 days Fertilized pelagic eggs (up to 1 mm) Competent larvae ready to settle from hatch 23 ‒ 40 hours following the plankton are carried by night-time fertilization. flood tides from the open ocean to nursery areas. Late juvenile Early juvenile 150 ‒ 400 mm TL (5.9 ‒ 15.7 in) 30 ‒ 150 mm TL (1.9 ‒ 5.9 in) 1 ‒ 4 years 10 ‒ 12 months Natural Prey Groupers change their diet as they grow. Juveniles feed mostly on crustaceans, while Early juveniles settle from the plankton into a variety of nursery areas including inshore algal beds, where they will live for up to one year. At 10 ‒ 12 months Nassau grouper move to patch reefs in shallow-water areas where they remain for several Shrimp Spawning Aggregations Amphipods Some Nassau grouper may change sex from female to male when they reach a total length of between 300 and 800 mm (11.9 ‒ 31.5 in). Spider crab Spiny lobster During the full moon of winter months Nassau grouper migrate Octopus up to hundreds of kilometers to form large spawning aggregations at specific locations. 1. Four color phases - barred, white belly, bicolor, and dark are observed during courtship and spawning. 2. Multiple males and at least one female break away from the larger group and rush upwards prior to spawning. Several species of reef fish 3 & 4. As the spawning rush reaches a peak, eggs and sperm are released into the water and the fish rapidly descend back to the bottom. -

Azores Ecoregion Published 12 December 2019

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Azores ecoregion Published 12 December 2019 3.1 Azores ecoregion – Ecosystem overview Table of contents Ecoregion description ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Key signals within the environment and the ecosystem .............................................................................................................................. 2 Pressures ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 State of the ecosystem components ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 Sources and acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Sources and references .............................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Ecoregion description For this overview, the Azores ecoregion corresponds to the Azores Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) inside ICES Subarea 10 (Figure 1). The ecoregion lies within a much larger open ocean ecosystem, and straddles the Mid-Atlantic Ridge -

Updated Checklist of Marine Fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the Proposed Extension of the Portuguese Continental Shelf

European Journal of Taxonomy 73: 1-73 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2014.73 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2014 · Carneiro M. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:9A5F217D-8E7B-448A-9CAB-2CCC9CC6F857 Updated checklist of marine fishes (Chordata: Craniata) from Portugal and the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf Miguel CARNEIRO1,5, Rogélia MARTINS2,6, Monica LANDI*,3,7 & Filipe O. COSTA4,8 1,2 DIV-RP (Modelling and Management Fishery Resources Division), Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, Av. Brasilia 1449-006 Lisboa, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 3,4 CBMA (Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology), Department of Biology, University of Minho, Campus de Gualtar, 4710-057 Braga, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] * corresponding author: [email protected] 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:90A98A50-327E-4648-9DCE-75709C7A2472 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:1EB6DE00-9E91-407C-B7C4-34F31F29FD88 7 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:6D3AC760-77F2-4CFA-B5C7-665CB07F4CEB 8 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:48E53CF3-71C8-403C-BECD-10B20B3C15B4 Abstract. The study of the Portuguese marine ichthyofauna has a long historical tradition, rooted back in the 18th Century. Here we present an annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Portuguese waters, including the area encompassed by the proposed extension of the Portuguese continental shelf and the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ). The list is based on historical literature records and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history collections, together with new revisions and occurrences. -

NOI Nassau Grouper

Sent via electronic mail April 6, 2020 Wilbur Ross, Secretary of Commerce Chris Oliver, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Department of Commerce National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration 1401 Constitution Ave., NW 1315 East-West Highway Washington, DC 20230 Silver Spring, MD 20910 [email protected] [email protected] RE: 60-Day Notice of Intent to Sue Regarding Violations of the Endangered Species Act; Failure to Designate Critical Habitat for the Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus) Dear Mr. Ross and Mr. Oliver: This letter serves as a sixty-day notice of intent to sue the National Marine Fisheries Service (Service) over violations of Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act (Act), 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq. This notice is submitted on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, and Miami Waterkeeper. Specifically, the Service has failed to designate critical habitat for Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus). Id. §§ 1533(a)(3)(A), 1533(b)(6)(C). The Service’s failure deprives the grouper important protections and puts it at further risk of extinction. This letter is provided pursuant to the 60-day notice requirement of the citizen suit provision of the Act, to the extent that such notice is deemed necessary by a court. Id. § 1540(g). A. The ESA Requires the Service to Designate Critical Habitat for Nassau Grouper In enacting the ESA, Congress recognized that certain species “have been so depleted in numbers that they are in danger of or threatened with extinction.” Id. § 1531(a)(2). Accordingly, a primary purpose of the ESA is “to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, [and] to provide a program for the conservation of such . -

Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus Striatus) in St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands, with Evidence for a Spawning Aggregation Site Recovery

Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus) in St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands, with Evidence for a Spawning Aggregation Site Recovery ELIZABETH KADISON, RICHARD S. NEMETH, JEREMIAH BLONDEAU, TYLER SMITH, and JACQUI CALNAN Center for Marine and Environmental Studies, University of the Virgin Islands 2 John Brewers Bay, St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands ABSTRACT The exploitation by fishing of fish spawning aggregations has caused many to disappear over the last fifty years, and has been a primary cause of dramatic stock declines of several large snapper and grouper species Caribbean-wide. In the USVI and Puerto Rico, the major Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus) spawning aggregation sites were fished to extinction the 1970s, and although the species is now federally protected, most sites show no signs of recovery. In 2003, Nassau grouper were found aggregating in small numbers to spawn on an offshore reef south of St. Thomas called the Grammanik Bank. The bank was seasonally, from February to May, closed to all bottom fishing beginning in 2005 due to the aggregating of the yellowfin grouper (Mycteroperca venenosa) on the site. Since 2005, increased numbers, a significantly greater mean size, and a larger size range of Nassau grouper have been documented on the bank. The fish are spatially and temporally mixed with yellowfin grouper during courtship, and it is believed this behavior may be an artifact of decreased numbers of Nassau, now using the yellowfin as surrogate aggregation members. It is doubtful that any other large Nassau grouper spawning aggregation sites remain in the USVI, so the effectiveness of the Grammanik Bank fishing closure may play a significant role in the recovery of local stocks. -

Atlas Over Danske Saltvandsfisk Spidstandet Blankesten

Atlas over danske saltvandsfisk Spidstandet blankesten Pagellus bogaraveo (Brünnich, 1768) Af Henrik Carl Spidstandet blankesten på 32,3 cm fra fiskehandler på Sicilien, 16. juli 2016. © Henrik Carl. Projektet er finansieret af Aage V. Jensen Naturfond Alle rettigheder forbeholdes. Det er tilladt at gengive korte stykker af teksten med tydelig kildehenvisning. Teksten bedes citeret således: Carl, H. 2017. Atlas over danske saltvandsfisk – Spidstandet blankesten. Statens Naturhistoriske Museum. Online-udgivelse, november 2017. Systematik og navngivning Arten blev oprindelig beskrevet som Sparus bogaraveo Brünnich, 1768. Senere blev den flyttet til slægten Pagellus Valenciennes, 1830. Med den nuværende systematik omfatter slægten seks arter (Froese & Pauly 2015), hvoraf tre kendes fra danske farvande. Foruden spidstandet blankesten drejer det sig om rød blankesten (P. erythrinus) og akarnanisk blankesten (P. acarne). I hovedparten af litteraturen fra 1800-tallet og størstedelen af 1900-tallet optræder den spidstandede blankesten imidlertid under navnet Pagellus centrodontus Delaroche, 1809. Genetiske undersøgelser tyder på, at arten er tættest beslægtet med akarnanisk blankesten (Linde et al. 2004). Det officielle danske navn er spidstandet blankesten (Carl et al. 2004) – og det er et navn, der er blevet brugt siden første halvdel af 1800-tallet (Krøyer 1838-40). Navnet er en oversættelse af det tidligere brugte artsnavn ”centrodontus”. I lidt ældre bøger optræder den under navne som almindelig blankesten, rød havrude og spansk blankesten. Ingen af disse bør bruges, og specielt de to førstnævnte er uheldige, da de også er de officielle danske navne for henholdsvis Pagrus pagrus og Dentex gibbosus. Selve navnet blankesten er brugt om havruder helt tilbage i 1700-tallet (Brünnich 1771), og det bruges nu om arter fra fire forskellige slægter. -

Movement Patterns of Goliath Grouper Epinephelus Itajara Around Southeast Cuba: Implications for Conservation

Vol. 7: 243–247, 2009 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Printed July 2009 doi: 10.3354/esr00192 Endang Species Res Published online July 1, 2009 Contribution to the Theme Section ’Range-wide status and conservation of the goliath grouper’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Movement patterns of goliath grouper Epinephelus itajara around southeast Cuba: implications for conservation F. Pina-Amargós1,*, G. González-Sansón2 1Centro de Investigaciones de Ecosistemas Costeros, Cayo Coco, Morón, Ciego de Ávila, CP 69 400, Cuba 2Centro de Investigaciones Marinas, Calle 16 No. 118 entre 1ra y 3ra, Ciudad de la Habana, Cuba ABSTRACT: Goliath grouper Epinephelus itajara is the largest grouper in the western hemisphere. Recently, populations have experienced dramatic declines that have become a major cause of con- cern for scientists and conservationists. It is essential for conservationists and managers to under- stand the species’ movement patterns if marine protected areas are to be effectively designed. We present results of goliath grouper movements following conventional tagging within and adjacent to the Jardines de la Reina Archipelago, which includes the Caribbean’s largest marine reserve. Five individuals were tagged in 2001 and tracked until 2003, with 541 underwater resightings through summer 2002 at the tagging sites. No goliath grouper were resighted after July 2002 at Jardines de la Reina diving sites. In February 2002, 1 individual was caught 36 km northeast of the tagging site. In August 2002, a second tagged specimen was caught 77 km southeast of the tagging site, while in August 2003, 2 individuals were captured 168 km southeast of the tagging site, at a possible spawn- ing aggregation site.