Movement Patterns of Goliath Grouper Epinephelus Itajara Around Southeast Cuba: Implications for Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Book (PDF)

e · ~ e t · aI ' A Field Guide to Grouper and Snapper Fishes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Family: SERRANIDAE, Subfamily: EPINEPHELINAE and Family: LUTJANIDAE) P. T. RAJAN Andaman & Nicobar Regional Station Zoological Survey of India Haddo, Port Blair - 744102 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Rajan, P. T. 2001. Afield guide to Grouper and Snapper Fishes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. (Published - Director, Z.5.1.) Published : December, 2001 ISBN 81-85874-40-9 Front cover: Roving Coral Grouper (Plectropomus pessuliferus) Back cover : A School of Blue banded Snapper (Lutjanus lcasmira) © Government of India, 2001 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher'S consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE Indian Rs. 400.00 Foreign $ 25; £ 20 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4, AJe Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building, (13th Floor), Nizam Palace, Calcutta-700 020 after laser typesetting by Computech Graphics, Calcutta 700019 and printed at Power Printers, New Delhi - 110002. -

Epinephelus Drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / None

click for previous page 1340 Bony Fishes Epinephelus drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / None. FAO names: En - Speckled hind; Fr - Mérou grivelé; Sp - Mero pintaroja. Diagnostic characters: Body depth subequal to head length, 2.4 to 2.6 times in standard length (for fish 20 to 43 cm standard length). Nostrils subequal; preopercle rounded, evenly serrate. Gill rakers on first arch 9 or 10 on upper limb, 17 or 18 on lower limb, total 26 to 28. Dorsal fin with 11 spines and 15 or 16 soft rays, the membrane incised between the anterior spines; anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays; caudal fin trun- cate or slightly emarginate, the corners acute; pectoral-fin rays 18. Scales strongly ctenoid, about 125 lateral-scale series; lateral-line scales 72 to 76. Colour: adults (larger than 33 cm) dark reddish brown, densely covered with small pearly white spots; juveniles (less than 20 cm) bright yellow, covered with small bluish white spots. Size: Maximum about 110 cm; maximum weight 30 kg. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Adults inhabit offshore rocky bottoms in depths of 25 to 183 m but are most common between 60 and 120 m.Females mature at 4 or 5 years of age (total length 45 to 60 cm).Spawning oc- curs from July to September, and a large female may produce up to 2 million eggs at 1 spawning. Back-calculated total lengths for fish aged 1 to 15 years are 19, 32, 41, 48, 53, 57, 61, 65, 68, 71, 74, 77, 81, 84, and 86 cm; the maximum age attained is at least 25 years, and the largest specimen measured was 110 cm. -

Epinephelus Chlorostigma, Brownspotted Grouper

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T118358386A100463851 Scope: Global Language: English Epinephelus chlorostigma, Brownspotted Grouper Assessment by: Fennessy, S., Choat, J.H., Nair, R. & Robinson, J. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Fennessy, S., Choat, J.H., Nair, R. & Robinson, J. 2018. Epinephelus chlorostigma. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T118358386A100463851. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T118358386A100463851.en Copyright: © 2018 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: Arizona State University; BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information provided. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ Taxonomy Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia Chordata Actinopterygii Perciformes Epinephelidae Taxon Name: Epinephelus chlorostigma (Valenciennes, 1828) Synonym(s): • Serranus areolatus ssp. -

Diet Composition of Juvenile Black Grouper (Mycteroperca Bonaci) from Coastal Nursery Areas of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 77(3): 441–452, 2005 NOTE DIET COMPOSITION OF JUVENILE BLACK GROUPER (MYCTEROPERCA BONACI) FROM COASTAL NURSERY AREAS OF THE YUCATÁN PENINSULA, MEXICO Thierry Brulé, Enrique Puerto-Novelo, Esperanza Pérez-Díaz, and Ximena Renán-Galindo Groupers (Epinephelinae, Epinephelini) are top-level predators that influence the trophic web of coral reef ecosystems (Parrish, 1987; Heemstra and Randall, 1993; Sluka et al., 2001). They are demersal mesocarnivores and stalk and ambush preda- tors that sit and wait for larger moving prey such as fish and mobile invertebrates (Cailliet et al., 1986). Groupers contribute to the ecological balance of complex tropi- cal hard-bottom communities (Sluka et al., 1994), and thus large changes in their populations may significantly alter other community components (Parrish, 1987). The black grouper (Mycteroperca bonaci Poey, 1860) is an important commercial and recreational fin fish resource in the western Atlantic region (Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). The southern Gulf of Mexico grouper fishery is currently considered to be deteriorated and M. bonaci, along with red grouper (Epinephelus morio Valenciennes, 1828) and gag (Mycteroperca microlepis Goode and Bean, 1880), is one of the most heavily exploited fish species in this region (Co- lás-Marrufo et al., 1998; SEMARNAP, 2000). Currently, M. bonaci is considered a threatened species (Morris et al., 2000; IUCN, 2003) and has been classified as vul- nerable in U.S. waters because male biomass in the Atlantic dropped from 20% in 1982 to 6% in 1995 (Musick et al., 2000). The black grouper is usually found on irregular bottoms such as coral reefs, drop- off walls, and rocky ledges, at depths from 10 to 100 m (Roe, 1977; Manooch and Mason, 1987; Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). -

V a Tion & Management of Reef Fish Sp a Wning Aggrega Tions

handbook CONSERVATION & MANAGEMENT OF REEF FISH SPAWNING AGGREGATIONS A Handbook for the Conservation & Management of Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations © Seapics.com Without the Land and the Sea, and their Bounties, the People and their Traditional Ways would be Poor and without Cultural Identity Fijian Proverb Why a Handbook? 1 What are Spawning Aggregations? 2 How to Identify Spawning Aggregations 2 Species that Aggregate to Spawn 2 Contents Places Where Aggregations Form 9 Concern for Spawning Aggregations 10 Importance for Fish and Fishermen 10 Trends in Exploited Aggregations 12 Managing & Conserving Spawning Aggregations 13 Research and Monitoring 13 Management Options 15 What is SCRFA? 16 How can SCRFA Help? 16 SCRFA Work to Date 17 Useful References 18 SCRFA Board of Directors 20 Since 2000, scientists, fishery managers, conservationists and politicians have become increasingly aware, not only that many commercially important coral reef fish species aggregate to spawn (reproduce) but also that these important reproductive gatherings are particularly susceptible to fishing. In extreme cases, when fishing pressure is high, aggregations can dwindle and even cease to form, sometimes within just a few years. Whether or not they will recover and what the long-term effects on the fish population(s) might be of such declines are not yet known. We do know, however, that healthy aggregations tend to be associated with healthy fisheries. It is, therefore, important to understand and better protect this critical part of the life cycle of aggregating species to ensure that they continue to yield food and support livelihoods. Why a Handbook? As fishing technology improved in the second half of the twentieth century, engines came to replace sails and oars, the cash economy developed rapidly, and human populations and demand for seafood grew, the pressures on reef fishes for food, and especially for money, increased enormously. -

Nassau Grouper

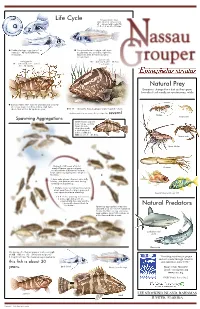

Life Cycle Pelagic juvenile stage (Late larval to early juvenile) 25 ‒ 30 mm total length (TL) (1.0 ‒ 1.2 in) 35 ‒ 50 days Fertilized pelagic eggs (up to 1 mm) Competent larvae ready to settle from hatch 23 ‒ 40 hours following the plankton are carried by night-time fertilization. flood tides from the open ocean to nursery areas. Late juvenile Early juvenile 150 ‒ 400 mm TL (5.9 ‒ 15.7 in) 30 ‒ 150 mm TL (1.9 ‒ 5.9 in) 1 ‒ 4 years 10 ‒ 12 months Natural Prey Groupers change their diet as they grow. Juveniles feed mostly on crustaceans, while Early juveniles settle from the plankton into a variety of nursery areas including inshore algal beds, where they will live for up to one year. At 10 ‒ 12 months Nassau grouper move to patch reefs in shallow-water areas where they remain for several Shrimp Spawning Aggregations Amphipods Some Nassau grouper may change sex from female to male when they reach a total length of between 300 and 800 mm (11.9 ‒ 31.5 in). Spider crab Spiny lobster During the full moon of winter months Nassau grouper migrate Octopus up to hundreds of kilometers to form large spawning aggregations at specific locations. 1. Four color phases - barred, white belly, bicolor, and dark are observed during courtship and spawning. 2. Multiple males and at least one female break away from the larger group and rush upwards prior to spawning. Several species of reef fish 3 & 4. As the spawning rush reaches a peak, eggs and sperm are released into the water and the fish rapidly descend back to the bottom. -

Academic Paper on “Restricting the Size of Groupers (Serranidae

ACADEMIC PAPER ON “RESTRICTING THE SIZE OF GROUPERS (SERRANIDAE) EXPORTED FROM INDONESIA IN THE LIVE REEF FOOD FISH TRADE” Coastal and Marine Resources Management in the Coral Triangle-Southeast Asia (TA 7813-REG) Tehcnical Report ACADEMIC PAPER ON RESTRICTING THE SIZE OFLIVE GROUPERS FOR EXPORT ACADEMIC PAPER ON “RESTRICTING THE SIZE OF GROUPERS (SERRANIDAE) EXPORTED FROM INDONESIA IN THE LIVE REEF FOOD FISH TRADE” FINAL VERSION COASTAL AND MARINE RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN THE CORAL TRIANGLE: SOUTHEAST ASIA, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, PHILIPPINES (TA 7813-REG) ACADEMIC PAPER ON RESTRICTING THE SIZE OFLIVE GROUPERS FOR EXPORT Page i FOREWORD Indonesia is the largest exporter of live groupers for the live reef fish food trade. This fisheries sub-sector plays an important role in the livelihoods of fishing communities, especially those living on small islands. As a member of the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI), in partnership with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) under RETA [7813], Indonesia (represented by a team from Hasanuddin University) has compiled this academic paper as a contribution towards sustainable management of live reef fish resources in Indonesia. Challenges faced in managing the live grouper fishery and trade in Indonesia include the ongoing activities and practices which damage grouper habitat; the lack of protection for grouper spawning sites; overfishing of groupers which have not yet reached sexual maturity/not reproduced; and the prevalence of illegal and unreported fishing for live groupers. These factors have resulted in declining wild grouper stocks. The Aquaculture sector is, at least as yet, unable to replace or enable a balanced wild caught fishery, and thus there is still a heavy reliance on wild-caught groupers. -

Fish Assemblages Associated with Red Grouper Pits at Pulley Ridge, A

419 Abstract—Red grouper (Epineph- elus morio) modify their habitat by Fish assemblages associated with red grouper excavating sediment to expose rocky pits, providing structurally complex pits at Pulley Ridge, a mesophotic reef in the habitat for many fish species. Sur- Gulf of Mexico veys conducted with remotely op- erated vehicles from 2012 through 2015 were used to characterize fish Stacey L. Harter (contact author)1 assemblages associated with grouper Heather Moe1 pits at Pulley Ridge, a mesophotic 2 coral ecosystem and habitat area John K. Reed of particular concern in the Gulf Andrew W. David1 of Mexico, and to examine whether invasive species of lionfish (Pterois Email address for contact author: [email protected] spp.) have had an effect on these as- semblages. Overall, 208 grouper pits 1 Southeast Fisheries Science Center were examined, and 66 fish species National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA were associated with them. Fish as- 3500 Delwood Beach Road semblages were compared by using Panama City, Florida 32408 several factors but were considered 2 Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute to be significantly different only on Florida Atlantic University the basis of the presence or absence 5600 U.S. 1 North of predator species in their pit (no Fort Pierce, Florida 34946 predators, lionfish only, red grou- per only, or both lionfish and red grouper). The data do not indicate a negative effect from lionfish. Abun- dances of most species were higher in grouper pits that had lionfish, and species diversity was higher in grouper pits with a predator (lion- The red grouper (Epinephelus morio) waters (>70 m) of the shelf edge and fish, red grouper, or both). -

NOI Nassau Grouper

Sent via electronic mail April 6, 2020 Wilbur Ross, Secretary of Commerce Chris Oliver, Assistant Administrator for Fisheries Department of Commerce National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration 1401 Constitution Ave., NW 1315 East-West Highway Washington, DC 20230 Silver Spring, MD 20910 [email protected] [email protected] RE: 60-Day Notice of Intent to Sue Regarding Violations of the Endangered Species Act; Failure to Designate Critical Habitat for the Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus) Dear Mr. Ross and Mr. Oliver: This letter serves as a sixty-day notice of intent to sue the National Marine Fisheries Service (Service) over violations of Section 4 of the Endangered Species Act (Act), 16 U.S.C. § 1531 et seq. This notice is submitted on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity, WildEarth Guardians, and Miami Waterkeeper. Specifically, the Service has failed to designate critical habitat for Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus). Id. §§ 1533(a)(3)(A), 1533(b)(6)(C). The Service’s failure deprives the grouper important protections and puts it at further risk of extinction. This letter is provided pursuant to the 60-day notice requirement of the citizen suit provision of the Act, to the extent that such notice is deemed necessary by a court. Id. § 1540(g). A. The ESA Requires the Service to Designate Critical Habitat for Nassau Grouper In enacting the ESA, Congress recognized that certain species “have been so depleted in numbers that they are in danger of or threatened with extinction.” Id. § 1531(a)(2). Accordingly, a primary purpose of the ESA is “to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, [and] to provide a program for the conservation of such . -

Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus Striatus) in St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands, with Evidence for a Spawning Aggregation Site Recovery

Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus) in St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands, with Evidence for a Spawning Aggregation Site Recovery ELIZABETH KADISON, RICHARD S. NEMETH, JEREMIAH BLONDEAU, TYLER SMITH, and JACQUI CALNAN Center for Marine and Environmental Studies, University of the Virgin Islands 2 John Brewers Bay, St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands ABSTRACT The exploitation by fishing of fish spawning aggregations has caused many to disappear over the last fifty years, and has been a primary cause of dramatic stock declines of several large snapper and grouper species Caribbean-wide. In the USVI and Puerto Rico, the major Nassau grouper (Epinephelus striatus) spawning aggregation sites were fished to extinction the 1970s, and although the species is now federally protected, most sites show no signs of recovery. In 2003, Nassau grouper were found aggregating in small numbers to spawn on an offshore reef south of St. Thomas called the Grammanik Bank. The bank was seasonally, from February to May, closed to all bottom fishing beginning in 2005 due to the aggregating of the yellowfin grouper (Mycteroperca venenosa) on the site. Since 2005, increased numbers, a significantly greater mean size, and a larger size range of Nassau grouper have been documented on the bank. The fish are spatially and temporally mixed with yellowfin grouper during courtship, and it is believed this behavior may be an artifact of decreased numbers of Nassau, now using the yellowfin as surrogate aggregation members. It is doubtful that any other large Nassau grouper spawning aggregation sites remain in the USVI, so the effectiveness of the Grammanik Bank fishing closure may play a significant role in the recovery of local stocks. -

Modifications to Gray Triggerfish Catch Levels

3/5/2021 Modifications to Gray Triggerfish Catch Levels Final Framework Action to the Fishery Management Plan for Reef Fish Resources of the Gulf of Mexico Including Environmental Assessment, Regulatory Impact Review, and Regulatory Flexibility Analysis March 2021 This is a publication of the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council Pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. NA20NMF4410011. This page intentionally blank ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT COVER SHEET Name of Action Framework Action to the Fishery Management Plan for Reef Fish Resources in the Gulf of Mexico: Modifications to Gray Triggerfish Catch Levels including Environmental Assessment, Regulatory Impact Review, and Regulatory Flexibility Act Analysis. Responsible Agencies and Contact Persons Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Council (Council) 813-348-1630 4107 W. Spruce Street, Suite 200 813-348-1711 (fax) Tampa, Florida 33607 [email protected] Carly Somerset ([email protected]) Gulf Council Website National Marine Fisheries Service (Lead Agency) 727-824-5305 Southeast Regional Office 727-824-5308 (fax) 263 13th Avenue South SERO Website St. Petersburg, Florida 33701 Kelli O’Donnell ([email protected]) Type of Action ( ) Administrative ( ) Legislative ( ) Draft (X) Final This Environmental Assessment is being prepared using the 2020 CEQ NEPA Regulations. The effective date of the 2020 CEQ NEPA Regulations was September 14, 2020, and reviews begun after this date are required to apply the 2020 regulations unless there is a clear and fundamental conflict with an applicable statute. 85 Fed. Reg. at 43372-73 (§§ 1506.13, 1507.3(a)). This Environmental Assessment began on January 28, 2021, and accordingly proceeds under the 2020 regulations. -

Epinephelus Lanceolatus (Bloch, 1790)

230 Capture-based aquaculture: global overview Epinephelus lanceolatus (Bloch, 1790) FIGURE 19 Giant grouper (Epinephelus lanceolatus) FAO TABLE 10 Characteristics of the giant grouper, Epinephelus lanceolatus Common names: Giant grouper, Queensland grouper Size and age: 270 cm TL; max. published weight: 455.0 kg Environment: Reef-associated; brackish; marine; depth range 1–100 m Climate: Tropical; 28°N - 39°S, 24°E - 122°W Importance: Important in subsistence fisheries, commercial aquaculture, recreational gamefish. Cultured in Taiwan PC. In live reef fish markets. Juveniles sold in ornamental trade as “bumblebee grouper”. Resilience: Very low, minimum population doubling time more than 14 years. Biology and ecology: The largest bony fish found in coral reefs. Common in shallow waters. Found in caves or wrecks; also in estuaries, from shore and in harbours. Juveniles secretive in reefs and rarely seen. Feeds on spiny lobsters, fishes, including small sharks and batoids, and juvenile sea turtles and crustaceans. Nearly wiped out in heavily fished areas. Large individuals may be ciguatoxic. Source: Modified from FishBase (Froese and Pauly, 2007). FIGURE 20 Distribution of Epinephelus lanceolatus (FishBase, 2007) Capture-based aquaculture of groupers 231 Epinephelus malabaricus (Bloch and Schneider, 1801) FIGURE 21 Malabar grouper (Epinephelus malabaricus) IRST COURTESY COURTESY OF D. F TABLE 11 Characteristics of the Malabar grouper, Epinephelus malabaricus Common names: Malabar grouper, estuary grouper, green grouper Size and age: 234 cm TL; max. published weight: 150.0 kg Environment: Reef-associated; amphidromous; brackish; marine; depth range 0–150 m Climate: Tropical; 30°N - 32°S, 29°E - 173°W Importance: High value commercial and recreational fisheries and aquaculture.