V a Tion & Management of Reef Fish Sp a Wning Aggrega Tions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BONY FISHES 602 Bony Fishes

click for previous page BONY FISHES 602 Bony Fishes GENERAL REMARKS by K.E. Carpenter, Old Dominion University, Virginia, USA ony fishes constitute the bulk, by far, of both the diversity and total landings of marine organisms encoun- Btered in fisheries of the Western Central Atlantic.They are found in all macrofaunal marine and estuarine habitats and exhibit a lavish array of adaptations to these environments. This extreme diversity of form and taxa presents an exceptional challenge for identification. There are 30 orders and 269 families of bony fishes presented in this guide, representing all families known from the area. Each order and family presents a unique suite of taxonomic problems and relevant characters. The purpose of this preliminary section on technical terms and guide to orders and families is to serve as an introduction and initial identification guide to this taxonomic diversity. It should also serve as a general reference for those features most commonly used in identification of bony fishes throughout the remaining volumes. However, I cannot begin to introduce the many facets of fish biology relevant to understanding the diversity of fishes in a few pages. For this, the reader is directed to one of the several general texts on fish biology such as the ones by Bond (1996), Moyle and Cech (1996), and Helfman et al.(1997) listed below. A general introduction to the fisheries of bony fishes in this region is given in the introduction to these volumes. Taxonomic details relevant to a specific family are explained under each of the appropriate family sections. The classification of bony fishes continues to transform as our knowledge of their evolutionary relationships improves. -

Appendix 4: Background Materials Provided to Participants Prior to the Workshop

Appendix 4: Background materials provided to participants prior to the workshop. Coral reef fin fish spawning closures f. Camouflage grouper (Epinephelus polyphekadion) Risk assessment workshop g. Flowery cod (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus) h. Greasy rockcod (Epinephelus tauvina) 12 – 13 May 2009 i. Spanish flag (stripey;Lutjanus carponotatus) 9am – 5pm Russell 1 & 2 j. Tuskfish Choerodon( spp.) Berkley’s On Ann Closures targeting coral trout afford some protection Rendezvous Hotel Brisbane to other coral reef fin fish species, although the magnitude of this effect is speculative. The imperative 255 Ann Street, Brisbane to explicitly consider other species rests on judgments concerning • the importance of each species to each sector, • the importance of each sector, and • the capacity of existing controls other than spawning closures to provide adequate protection. These judgments are a central theme of the workshop. Background An initial task for the workshop is identification of candidate alternatives. Any closure regime This workshop will explore candidate alternatives for implemented beyond 2008 needs to provide adequate spawning closures to be applied 2009 – 2013. protection for spawning coral reef fin fish species, The Fisheries (Coral Reef Fin Fish) Management Plan within a constraint that the impost on commercial 2003 introduced three nine-day spawning closures and recreational (including charter) fishing is no for coral reef fin fish on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). greater than for the period 2004 – 2008. ReefMAC The closures applied to the new moon periods in has recommended a five year package comprising two October, November and December for the years years (2009-2010) of no spawning closures followed 2004-2008. -

Target Fish Carnivores

TARGET FISH CARNIVORES WRASSES - LABRIDAE Thicklips Hemigymnus spp. Slingjaw Wrasse Epibulus insidiator Tripletail Wrasse Cheilinus trilobatus Redbreasted Wrasse Cheilinus fasciatus Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July 2016 1 Hogfish Bodianus spp. Tuskfish Choerodon spp. Moon Wrasse Thalassoma lunare Humphead Wrasse Cheilinus undulatus Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July 2016 2 GOATFISH - MULLIDAE Dash-dot Goatfish Parupeneus barberinus Doublebar Goatfish Parupeneus bifasciatus Manybar Goatfish Parupeneus multifasciatus SNAPPER - LUTJANIDAE Midnight Snapper Macolor macularis Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July 2016 3 Spanish Flag Snapper Lutjanus carponotatus Black-banded Snapper Lutjanus semicinctus Checkered Snapper Lutjanus decussatus Two-spot Snapper Lutjanus biguttatus Red Snapper Lutjanus bohar Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July 2016 4 GROUPER – SERRANIDAE Barramundi Cod Cromileptes altivelis Bluespotted Grouper Cephalopholis cyanostigma Peacock Grouper Cephalopholis argus Coral Grouper Cephalopholis miniata Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July 2016 5 Lyretails Variola albimarginata & Variola louti Honeycomb Grouper Epinephelus merra Highfin Grouper Epinephelus maculatus Flagtail Grouper Cephalopholis urodeta Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July 2016 6 Blacksaddle Coral Grouper Plectropomus laevis Large Groupers TRIGGERFISH - BALISTIDAE Titan Triggerfish Balistoides viridescens Barefoot Conservation | TARGET FISH CARNIVORES| July -

Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi

Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 (http://www.accessscience.com/) Article by: Boschung, Herbert Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Gardiner, Brian Linnean Society of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, United Kingdom. Publication year: 2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1036/1097-8542.680400) Content Morphology Euteleostei Bibliography Phylogeny Classification Additional Readings Clupeomorpha and Ostariophysi The most recent group of actinopterygians (rayfin fishes), first appearing in the Upper Triassic (Fig. 1). About 26,840 species are contained within the Teleostei, accounting for more than half of all living vertebrates and over 96% of all living fishes. Teleosts comprise 517 families, of which 69 are extinct, leaving 448 extant families; of these, about 43% have no fossil record. See also: Actinopterygii (/content/actinopterygii/009100); Osteichthyes (/content/osteichthyes/478500) Fig. 1 Cladogram showing the relationships of the extant teleosts with the other extant actinopterygians. (J. S. Nelson, Fishes of the World, 4th ed., Wiley, New York, 2006) 1 of 9 10/7/2015 1:07 PM Teleostei - AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education http://www.accessscience.com/content/teleostei/680400 Morphology Much of the evidence for teleost monophyly (evolving from a common ancestral form) and relationships comes from the caudal skeleton and concomitant acquisition of a homocercal tail (upper and lower lobes of the caudal fin are symmetrical). This type of tail primitively results from an ontogenetic fusion of centra (bodies of vertebrae) and the possession of paired bracing bones located bilaterally along the dorsal region of the caudal skeleton, derived ontogenetically from the neural arches (uroneurals) of the ural (tail) centra. -

Abstract for Submission to the 11Th International Coral Reef

Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations in Aceh, Sumatra: Local Knowledge of Occurrence and Status Authors: Campbell S.J., Mukmunin, A., Prasetia, R The Wildlife Conservation Society, Indonesian Marine Program, Jalan Pangrango 8, Bogor 16141, Indonesia Reef Fish Spawning Aggregations (FSA) are critical in the life cycle of the fishes that use this reproductive strategy as sources of larvae, but are also highly vulnerable to over exploitation. With the exception of the Komodo (Pet et al. 2005) little if any research has been focused on FSAs in Indonesia. Interview surveys were conducted among fishing communities on the island of Weh in northern Aceh in order to determine the level of awareness of FSAs among fishers; which reef fish species form FSAs; sites of aggregation formation; seasonal patterns; and to assess fishing pressure on and status of FSAs. Results show that many fishers possess reliable knowledge of spawning areas, species and times. Possible FSAs were reported from a number of areas on Weh island inside and outside protected areas. Of the 47 species of fish mentioned by respondents, we conclude that six species are very likely to form spawning aggregations in marine waters of Weh island. All six species were mentioned by more than 10 fishers, and included Bolbometopoton muricatum (Scaridae: Bumpheaded parrotfish), Cepahpholis miniata (Serranidae: Coral grouper) Variola louti (Serranidae: Yellow Edged Lyretail), Cheilinus undulatas (Labridae: Napolean wrasse), Thunnus albacares (Yellow fin tuna) and Caranx lugubris (Carangidae: Black Jack Trevally). FSAs in Aceh were areas targeted by fishers, although many were inside existing marine protected areas where prohibitions on netting from boats are in place. -

Age Estimates of Two Large Misty Grouper, Epinephelus Mystacinus

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Aquila Digital Community Gulf and Caribbean Research Volume 21 | Issue 1 2009 Age Estimates of Two Large Misty Grouper, Epinephelus mystacinus (Serranidae) from Bermuda with a Comparison of the Age of Tropical Groupers in the Western Atlantic Brian E. Luckhurst Marine Resources Division, Bermuda John M. Dean University of South Carolina DOI: 10.18785/gcr.2101.09 Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/gcr Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Luckhurst, B. E. and J. M. Dean. 2009. Age Estimates of Two Large Misty Grouper, Epinephelus mystacinus (Serranidae) from Bermuda with a Comparison of the Age of Tropical Groupers in the Western Atlantic. Gulf and Caribbean Research 21 (1): 73-77. Retrieved from http://aquila.usm.edu/gcr/vol21/iss1/9 This Short Communication is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gulf and Caribbean Research by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gulf and CaribbeanGulf Research and Caribbean Vol 21, 73-77,Research 2009 Vol 21, 73-77, 2009 Manuscript receivedManuscript January 7,received 2009; Januaryaccepted 7, February 2009; accepted 6, 2009 February 6, 2009 Gulf and Caribbean Research Vol 21, 73-77, 2009 Manuscript received January 7, 2009; accepted February 6, 2009 SHORT COMMUNICATIONSHORT COMMUNICATION SHORT COMMUNICATION AGE ESTIMATESAGE ESTIMATES OF TWO OF LARGE TWO MISTYLARGE GROUPER, MISTY GROUPER, AGE ESTIMATES OF TWO LARGE MISTY GROUPER, EPINEPHELUSEPINEPHELUS MYSTACINUS MYSTACINUS (SERRANIDAE) (SERRANIDAE) FROM BERMUDA FROM BERMUDA EPINEPHELUS MYSTACINUS (SERRANIDAE) FROM BERMUDA WITH A WITHCOMPARISON A COMPARISON OF THE OFAGE THE OF AGETROPICAL OF TROPICAL WITH A COMPARISON OF THE AGE OF TROPICAL GROUPERSGROUPERS IN THE WESTERNIN THE WESTERN ATLANTIC ATLANTIC GROUPERS IN THE WESTERN ATLANTIC Brian E. -

Download Book (PDF)

e · ~ e t · aI ' A Field Guide to Grouper and Snapper Fishes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands (Family: SERRANIDAE, Subfamily: EPINEPHELINAE and Family: LUTJANIDAE) P. T. RAJAN Andaman & Nicobar Regional Station Zoological Survey of India Haddo, Port Blair - 744102 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Rajan, P. T. 2001. Afield guide to Grouper and Snapper Fishes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. (Published - Director, Z.5.1.) Published : December, 2001 ISBN 81-85874-40-9 Front cover: Roving Coral Grouper (Plectropomus pessuliferus) Back cover : A School of Blue banded Snapper (Lutjanus lcasmira) © Government of India, 2001 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher'S consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE Indian Rs. 400.00 Foreign $ 25; £ 20 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4, AJe Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building, (13th Floor), Nizam Palace, Calcutta-700 020 after laser typesetting by Computech Graphics, Calcutta 700019 and printed at Power Printers, New Delhi - 110002. -

Epinephelus Drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent Synonyms / Misidentifications: None / None

click for previous page 1340 Bony Fishes Epinephelus drummondhayi Goode and Bean, 1878 EED Frequent synonyms / misidentifications: None / None. FAO names: En - Speckled hind; Fr - Mérou grivelé; Sp - Mero pintaroja. Diagnostic characters: Body depth subequal to head length, 2.4 to 2.6 times in standard length (for fish 20 to 43 cm standard length). Nostrils subequal; preopercle rounded, evenly serrate. Gill rakers on first arch 9 or 10 on upper limb, 17 or 18 on lower limb, total 26 to 28. Dorsal fin with 11 spines and 15 or 16 soft rays, the membrane incised between the anterior spines; anal fin with 3 spines and 9 soft rays; caudal fin trun- cate or slightly emarginate, the corners acute; pectoral-fin rays 18. Scales strongly ctenoid, about 125 lateral-scale series; lateral-line scales 72 to 76. Colour: adults (larger than 33 cm) dark reddish brown, densely covered with small pearly white spots; juveniles (less than 20 cm) bright yellow, covered with small bluish white spots. Size: Maximum about 110 cm; maximum weight 30 kg. Habitat, biology, and fisheries: Adults inhabit offshore rocky bottoms in depths of 25 to 183 m but are most common between 60 and 120 m.Females mature at 4 or 5 years of age (total length 45 to 60 cm).Spawning oc- curs from July to September, and a large female may produce up to 2 million eggs at 1 spawning. Back-calculated total lengths for fish aged 1 to 15 years are 19, 32, 41, 48, 53, 57, 61, 65, 68, 71, 74, 77, 81, 84, and 86 cm; the maximum age attained is at least 25 years, and the largest specimen measured was 110 cm. -

Diet Composition of Juvenile Black Grouper (Mycteroperca Bonaci) from Coastal Nursery Areas of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 77(3): 441–452, 2005 NOTE DIET COMPOSITION OF JUVENILE BLACK GROUPER (MYCTEROPERCA BONACI) FROM COASTAL NURSERY AREAS OF THE YUCATÁN PENINSULA, MEXICO Thierry Brulé, Enrique Puerto-Novelo, Esperanza Pérez-Díaz, and Ximena Renán-Galindo Groupers (Epinephelinae, Epinephelini) are top-level predators that influence the trophic web of coral reef ecosystems (Parrish, 1987; Heemstra and Randall, 1993; Sluka et al., 2001). They are demersal mesocarnivores and stalk and ambush preda- tors that sit and wait for larger moving prey such as fish and mobile invertebrates (Cailliet et al., 1986). Groupers contribute to the ecological balance of complex tropi- cal hard-bottom communities (Sluka et al., 1994), and thus large changes in their populations may significantly alter other community components (Parrish, 1987). The black grouper (Mycteroperca bonaci Poey, 1860) is an important commercial and recreational fin fish resource in the western Atlantic region (Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). The southern Gulf of Mexico grouper fishery is currently considered to be deteriorated and M. bonaci, along with red grouper (Epinephelus morio Valenciennes, 1828) and gag (Mycteroperca microlepis Goode and Bean, 1880), is one of the most heavily exploited fish species in this region (Co- lás-Marrufo et al., 1998; SEMARNAP, 2000). Currently, M. bonaci is considered a threatened species (Morris et al., 2000; IUCN, 2003) and has been classified as vul- nerable in U.S. waters because male biomass in the Atlantic dropped from 20% in 1982 to 6% in 1995 (Musick et al., 2000). The black grouper is usually found on irregular bottoms such as coral reefs, drop- off walls, and rocky ledges, at depths from 10 to 100 m (Roe, 1977; Manooch and Mason, 1987; Bullock and Smith, 1991; Heemstra and Randall, 1993). -

Nassau Grouper

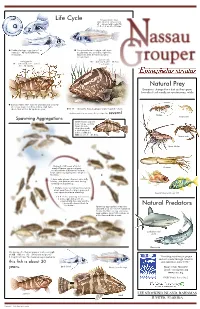

Life Cycle Pelagic juvenile stage (Late larval to early juvenile) 25 ‒ 30 mm total length (TL) (1.0 ‒ 1.2 in) 35 ‒ 50 days Fertilized pelagic eggs (up to 1 mm) Competent larvae ready to settle from hatch 23 ‒ 40 hours following the plankton are carried by night-time fertilization. flood tides from the open ocean to nursery areas. Late juvenile Early juvenile 150 ‒ 400 mm TL (5.9 ‒ 15.7 in) 30 ‒ 150 mm TL (1.9 ‒ 5.9 in) 1 ‒ 4 years 10 ‒ 12 months Natural Prey Groupers change their diet as they grow. Juveniles feed mostly on crustaceans, while Early juveniles settle from the plankton into a variety of nursery areas including inshore algal beds, where they will live for up to one year. At 10 ‒ 12 months Nassau grouper move to patch reefs in shallow-water areas where they remain for several Shrimp Spawning Aggregations Amphipods Some Nassau grouper may change sex from female to male when they reach a total length of between 300 and 800 mm (11.9 ‒ 31.5 in). Spider crab Spiny lobster During the full moon of winter months Nassau grouper migrate Octopus up to hundreds of kilometers to form large spawning aggregations at specific locations. 1. Four color phases - barred, white belly, bicolor, and dark are observed during courtship and spawning. 2. Multiple males and at least one female break away from the larger group and rush upwards prior to spawning. Several species of reef fish 3 & 4. As the spawning rush reaches a peak, eggs and sperm are released into the water and the fish rapidly descend back to the bottom. -

Academic Paper on “Restricting the Size of Groupers (Serranidae

ACADEMIC PAPER ON “RESTRICTING THE SIZE OF GROUPERS (SERRANIDAE) EXPORTED FROM INDONESIA IN THE LIVE REEF FOOD FISH TRADE” Coastal and Marine Resources Management in the Coral Triangle-Southeast Asia (TA 7813-REG) Tehcnical Report ACADEMIC PAPER ON RESTRICTING THE SIZE OFLIVE GROUPERS FOR EXPORT ACADEMIC PAPER ON “RESTRICTING THE SIZE OF GROUPERS (SERRANIDAE) EXPORTED FROM INDONESIA IN THE LIVE REEF FOOD FISH TRADE” FINAL VERSION COASTAL AND MARINE RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN THE CORAL TRIANGLE: SOUTHEAST ASIA, INDONESIA, MALAYSIA, PHILIPPINES (TA 7813-REG) ACADEMIC PAPER ON RESTRICTING THE SIZE OFLIVE GROUPERS FOR EXPORT Page i FOREWORD Indonesia is the largest exporter of live groupers for the live reef fish food trade. This fisheries sub-sector plays an important role in the livelihoods of fishing communities, especially those living on small islands. As a member of the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI), in partnership with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) under RETA [7813], Indonesia (represented by a team from Hasanuddin University) has compiled this academic paper as a contribution towards sustainable management of live reef fish resources in Indonesia. Challenges faced in managing the live grouper fishery and trade in Indonesia include the ongoing activities and practices which damage grouper habitat; the lack of protection for grouper spawning sites; overfishing of groupers which have not yet reached sexual maturity/not reproduced; and the prevalence of illegal and unreported fishing for live groupers. These factors have resulted in declining wild grouper stocks. The Aquaculture sector is, at least as yet, unable to replace or enable a balanced wild caught fishery, and thus there is still a heavy reliance on wild-caught groupers. -

Fish Assemblages Associated with Red Grouper Pits at Pulley Ridge, A

419 Abstract—Red grouper (Epineph- elus morio) modify their habitat by Fish assemblages associated with red grouper excavating sediment to expose rocky pits, providing structurally complex pits at Pulley Ridge, a mesophotic reef in the habitat for many fish species. Sur- Gulf of Mexico veys conducted with remotely op- erated vehicles from 2012 through 2015 were used to characterize fish Stacey L. Harter (contact author)1 assemblages associated with grouper Heather Moe1 pits at Pulley Ridge, a mesophotic 2 coral ecosystem and habitat area John K. Reed of particular concern in the Gulf Andrew W. David1 of Mexico, and to examine whether invasive species of lionfish (Pterois Email address for contact author: [email protected] spp.) have had an effect on these as- semblages. Overall, 208 grouper pits 1 Southeast Fisheries Science Center were examined, and 66 fish species National Marine Fisheries Service, NOAA were associated with them. Fish as- 3500 Delwood Beach Road semblages were compared by using Panama City, Florida 32408 several factors but were considered 2 Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute to be significantly different only on Florida Atlantic University the basis of the presence or absence 5600 U.S. 1 North of predator species in their pit (no Fort Pierce, Florida 34946 predators, lionfish only, red grou- per only, or both lionfish and red grouper). The data do not indicate a negative effect from lionfish. Abun- dances of most species were higher in grouper pits that had lionfish, and species diversity was higher in grouper pits with a predator (lion- The red grouper (Epinephelus morio) waters (>70 m) of the shelf edge and fish, red grouper, or both).