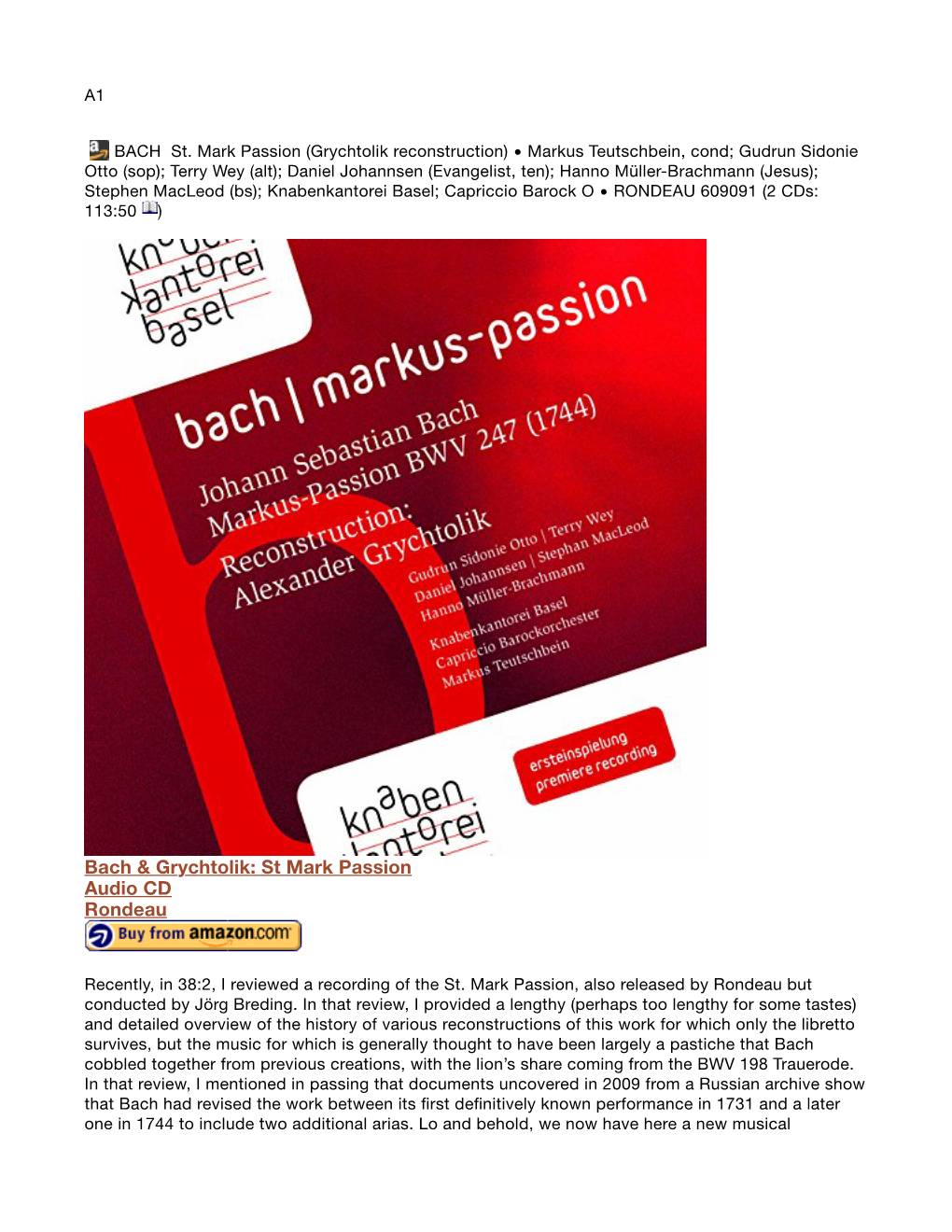

Bach & Grychtolik: St Mark Passion Audio CD Rondeau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chor an Der Saar 1/2005

0151.sabu.ztg.umbr.01.05.411 26.01.2005 15:57 Uhr Seite 1 U 217 44 F Zeitschrift 49. Jahrgang des Saar- Nr.1 Januar/Februar 2005 www.saar-saengerbund.de Sängerbundes Heftpreis: € 1,– Sonderprojekte des Saar-Sängerbundes 2005 Chorleiterinnen- und ChorleiterChor Jazzworkshop ChorleiterInnen-Ausbildung LandesChorwettbewerb Saar 0151.sabu.ztg.umbr.01.05.411 26.01.2005 15:57 Uhr Seite 2 Inhalt Neuer Redakteur Chorleiterinnen- und IHREM Engagement, IHREN Anregungen Chorleiterversammlung 2005 2 und von IHREN qualitätsvollen Beiträgen – Chorleiterinnen- und die durchaus auch kritisch sein dürfen, wenn es berechtigt erscheint. In diesem ChorleiterChor des SSB 3 Sinne hoffe ich auf eine offene und kon- Konzert zum neuen Jahr 2005 4 struktive Zusammenarbeit mit Ihnen für eine lesenswerte Zeitung „Chor an der Rückblick „Chor total“ 6 Saar“. LandesChorwettbewerb Ihr Saar 2005 7 Rainer Knauf Aus dem Chor- und Vereinsleben: Sängerkreis Homburg 7 Sängerkreis Merzig-Wadern 8 Sängerkreis Neunkirchen 9 Sängerkreis Saarbrücken 12 Sängerkreis Saarlouis 17 Sängerkreis St. Wendel 22 Chorleiterinnen- Sängerkreis St. Ingbert 27 und Chorleiterver- Zum Gedenken 31 Veranstaltungskalender 31 Verehrte Leserinnen und Leser, sammlung 2005 liebe Freunde der Chormusik, Nach der Satzung des Saar-Sängerbun- des e.V. sind seitens des Bundesmusik- mit Beginn des neuen Jahres hat mich der ausschusses jährlich die Empfehlungen Vorstand des Saar-Sängerbundes mit der der Chorleiterinnen und Chorleiter der Redaktion dieser Zeitung beauftragt – Mitgliedschöre einzuholen. Grund genug, mich Ihnen kurz vorzustel- len: Ich heiße Rainer Knauf, bin 38 Jahre Hiermit ergeht die Einladung zur und komme aus Saarbrücken. Neben mei- „Chorleiterinnen- und Chorleiterver- nen publizistischen Aktivitäten als Redak- sammlung“ 2005: teur und (Mit-)Herausgeber – derzeit z.B. -

A Critical Study of Five Reconstructions of Bach's Markuspassion BWV 247 with Particular Reference to the Parody Technique

A critical study of five reconstructions of Bach’s Markuspassion BWV 247 with particular reference to the parody technique Paula Fourie Supervisor: Professor John Hinch Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree MMus Department of Music University of Pretoria November 2010 © University of Pretoria Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their part in this dissertation: • Professor John Hinch for his guidance and supervision • Johann van der Sandt for guiding me to this topic and for providing scores and recordings of several of the reconstructions under discussion • Isobel Rycroft from the UP music library for her unwavering help in locating information sources • My parents who have shown that learning is a life-long quest • Etienne, for his patience and assistance with proofreading ©© Abstract A part of Johann Sebastian Bach’s musical duties in Leipzig was to present an annual setting of the passion for Good Friday Vespers. One such work was the Markuspassion, performed in 1731. Although the score of this companion work to the Matthäuspassion and Johannespassion has been lost, the original text of the Markuspassion is extant. Bach frequently made use of the parody technique in his compositions. This practice consisted of adapting existing music to a new text that was based on the rhyme scheme of the original one, resulting in two compositions essentially sung to the same music, barring a number of enforced changes. This particular feature of Bach’s compositional technique makes it possible that the lost music originally contained in the Markuspassion could be discovered within his oeuvre. In the late 19th century, Bach scholars began to research the possibility of reconstructing the Markuspassion, recognizing that it may have contained music parodied from other compositions basing, to a large extent, their research on textual comparison. -

LBW: Public-2

Chav compositor composicao Ano Detalhes duração Intérpretes ? Cembalo nach A. Vivaldi * Abel, Carl Fried Sonate für Viola da Gamb 1723-1 5'10 Veronika Hampe - Gambe Abel, K.F. Sonate für Viola da Gamb 1723-1 Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für Gitarren 1723-1 Moderato; 6'50 D.E. Lovell - Synth. Cantabile; Vivace Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für Gitarren 1723-1 Moderato; 6'50 D.E. Lovell - Synth. Cantabile; Vivace Adson, J. Aria für Flöte und BC 2'00 (P) 1969 Discos beverly LTDA conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Adson, J. Courtly masquino ayres 3 1590-1 5'06 (P) 1968 rozenblit conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Alain, Jehan 2 Stücke für Orgel 1911-1 Marie-Claire Alain Albéniz, I. Danzas españolas Op.37 1860-1 2-Tango; 2' Nr. ?? Tango 3-Malagueña Nr. 2: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 3: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Albéniz, I. Estudio sem luz 1860-1 3' Albéniz, I. Suite Española Op. 47 1860-1 Für Orchester 37'16 5. Asturias gesetzt von Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos 1. Granada (Serenata); 2. Cataluna (Curranda); 3. Sevilla; 4. Cádiz (Saeta); 5. Astúrias (arr. A. Segovia) (Leyenda); 6.Aragon (Fantasia); 7.Castilla (Sequidillas); 8. Cuba (Nocturno) Chav compositor composicao Ano Detalhes duração Intérpretes Orchesterzusatz: 8. Cordoba Nr. 1 Granada: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 1 Granada (5'20) : Julien Bream - Gitarre (P) 1968 DECCA Reihenfolge: 7, 5, 6, 4, 3, 1, 2, 8 New Philharmonia Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos Albicastro, H. Concerto Op. 7 Nr. 6 F-Du 1659-1 9'20 Süsdwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzheim Leitung: Paul Angerer Albinoni, T. -

Kiek 1/2002 Kopie

IINFORMATIONENNFORMATIONEN MEINUNGENMEINUNGEN TERMINETERMINE IIII // 20022002 Kirchenmusik im Erzbistum Köln Informationsdienst für KirchenmusikerInnen und Kirchenchöre Herausgeber: Referat für Kirchenmusik Abteilung Gemeindepastoral Hauptabteilung Seelsorge KiEK 2/2002 1 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Geleitwort 3 Nachklang derr Romreise der Chöre im Herbst 2001 4 Personalia 8 Aus den Dekanaten 10 Veranstaltungen 15 Fortbildung 20 Aus dem Kirchlichen Amtsblatt 25 Aktuelle Informationen 26 Berichte 29 C-Ausbildung 34 Rezensionen 35 Orgeln 37 Offene Stellen 40 Impressum 45 BEITRÄGE ZUM ABDRUCK IN DER NÄCHSTEN AUSGABE (MÄRZ 2003) ERBITTEN WIR ALS E-MAIL (ADRESSE IM IMPRESSUM) ODER PER POST AUF DISKETTE. BITTE NICHT ALS FAX. BITTE SENDEN SIE AUFGRUND DER BESSEREN VERARBEITUNG MÖG- LICHST UNFORMATIERTE DOKUMENTE EIN. AUCH FOTOS (AM BESTEN IN SCHWARZ-WEISS) WERDEN GERNE MIT EINGEARBEITET. REDAKTIONSSCHLUSS IST DER 3. FEBRUAR 2003 2 KiEK 2 / 2002 GELEITWORT Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, verfasst, der die Grundzüge dessen darstellt, was für Kirchenmusi-ker/innen aus dem Urheberrecht wich- mit dem Romnachtreffen am 23.06.2002 im tig ist zu wissen (in Musica Sacra wird der Artikel Maternushaus und dem abschließenden Evensong mit voraussichtlich im Oktober erscheinen). Wichtig ist Herrn Kardinal Meisner im Dom hat auch für uns die hier auf jeden Fall, darauf hinzuweisen, dass der Ver- Romreise endlich ein Ende. Es sind Wunden geblie- trag mit der VG-Musikedition über wissenschaftliche ben, aber es gibt auch erste zarte Pflanzen der Aussaat und nachgelassene Werke zum 31.12.2002 gekündigt von Rom, die erfreulich sind: Eine Umfrage unter den wurde und damit diese Werke nicht mehr mit einem Regionalkantoren ergab, dass die Romreise inhaltlich Pauschalvertrag abgegolten sind. Sollen also Werke nicht folgenlos geblieben ist. -

Thüringer Bachw Ochen 2015

3 Thüringer Bachwochen 2015 +49 (0) 361 . 37 42 0 TICKETS | HOTELBUCHUNG www.thueringer-bachwochen.de 1 Thüringer Bachwochen 27. MÄRZ – 19. APRIL Bach für Kinder 17. MÄRZ – 18. MÄRZ Weimarer Bachkantaten-Akademie 9. AUGUSt – 21. AUGUST Orgelwoche der Thüringer Bachwochen 26. SEPTEMBER – 12. OKTOBER Ein südkoreanischer Chor, der die westliche Kultur durch Bachs Mu- 2 3 sik erlebt, ein Akkordeonist, der sich die Goldberg-Variationen für sein Instrument zu Eigen macht, ein russischer Komponist, der im Gulag Präludien und Fugen im Gedenken an „Das Wohltemperierte Clavier“ schreibt – es sind ganz unterschiedliche Situa tionen, die Menschen mit Johann Sebastian Bach zusammenführen. Bach ist Herausforde- rung und Inspiration, seine Musik dient als Lehrstück, als Vorlage für Kommentare und als christliches Manifest; es ist ein ganzes Kaleido- skop, das man in und durch Bachs Musik entdecken kann. Dass Johann Sebastian Bach und seine Musik einzigartig sind, aber auch im Bezug zu ihrer Umwelt stehen, das möchten wir mit den Thüringer Bachwochen zeigen. Natürlich bringen wir seine Werke an den historischen Lebensorten zur Aufführung, aber wir zeigen auch seine Wirkung auf die Menschen. Bachs Musik war Anregung für Mendelssohn, Schostakowitsch und Schönberg, sie stellt einen Reiz dar für A-cappella-Ensembles wie SLIXS und einen Stargeiger wie Nigel Kennedy. Und wie sie heute dem Publikum nahe zu bringen ist, beschäftigt wohl alle gastierenden Musiker, allen voran die Solisten der Jumpstart Junior Stiftung, die sich in einer internationalen Ko- produktion mit neuen Aufführungsformen auseinandersetzen. DRESCHER & CHRISTOPH KESSEL VON SILVIUS Bach in seiner Vielfalt möchten wir zeigen, in dem wir ein Kalei- doskop von Bach-Sichten vorstellen, vom Rentsch-Portrait des jun- gen Bach 1715 bis zu den Bach-Hommagen unserer Zeit. -

Markus-Passion

Frauenkirche Dresden Carus 83.244 Johann Sebastian Bach Markus-Passion Dominique Horwitz amarcord Kölner Akademie Michael Alexander Willens Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) M arkus-Passion BW V 247 Rekonstruierte Fassung von Diethard Hellmann und Andreas Glöckner Dominique Horwitz, Sprecher amarcord Kölner Akademie · Michael Alexander Willens, Leitung Vor der Predigt / Before the Sermon 16 Rezit. (Evang., Jesus): 1:01 Und kam und fand sie schlafend 1 Chor: Geh, Jesu, geh zu deiner Pein 5:40 17 Arie (Sopran): 3:41 2 Rezit. (Evang., Chor): 1:06 Er kommt, er ist vorhanden Und nach zwei Tagen war Ostern 18 Rezit. (Evang., Judas): 0:36 3 Choral: Sie stellen uns wie Ketzern nach 0:52 Und alsbald, da er noch redete 4 Rezit. (Evang., Jesus):1:0519 Arie (Alt): 6:14 Jesus aber sprach: Lasst sie in Frieden Falsche Welt, dein schmeichelnd Küssen 5 Choral: Mir hat die Welt trüglich gericht’t 0:44 20 Rezit. (Evang., Jesus): 0:42 6 Rezit. (Evang., Jesus, Jünger):1:07Die aber legten ihre Hände an ihn Und am ersten Tage der süßen Brote 21 Choral: Jesu, ohne Missetat 1:07 7 Choral: Ich, ich und meine Sünden 0:53 22 Rezit. (Evang.): 0:23 8 Rezit. (Evang., Jesus):1:15Und die Jünger verließen ihn alle Er aber sprach zu ihnen 23 Choral: Ich will hier bei dir stehen 1:12 9 Arie (Alt): 6:32 Mein Heiland, dich vergess’ ich nicht Nach der Predigt / After the Sermon 10 Rezit. (Evang., Jesus): 0:30 Und da sie den Lobgesang gesprochen hatten 24 Arie (Tenor): 4:11 11 Choral: 1:17 Mein Tröster ist nicht mehr bei mir Wach auf, o Mensch, vom Sündenschlaf 25 Rezit. -

PH18084 Jubilaeumsbox Bookl 1C.Indd

15 CD Hans Rott Symphony No. 1 Johann von Herbeck Great Mass Francis Poulenc Stabat Mater Johann Joachim Quantz Flute Concertos Hector Berlioz Te Deum Anton Bruckner Symphony in D minor Alfred Schnittke Cello Sonatas Walter Braunfels String Quintet Franz von Suppé Requiem Hans Pfitzner Symphony op. 46 Staatskapelle Dresden, Münchner Rundfunkorchester, Philharmonie Festiva, Mozarteumorchester Salzburg Sir Colin Davis, Marcello Viotti, Helmuth Rilling, Krzysztof Penderecki, Constantin Trinks, Gerd Schaller CD 1 CD 2 Alfred Schnittke (1934 – 1998) Franz Xaver Gebel (1787 – 1843) Hoffmeister-Quartett Christoph Heidemann, Violine Cello Piano Works Double String Quintet d minor, op. 28 (1st in tracks 1-4, 3rd in tracks 5-8) for 4 Violins, 2 Violas and 4 Violoncellos 1 Epilogue from the ballet „Peer Gynt“ 1'41 Ulla Bundies, Violine for cello, piano and tape 1 Allegro 9'56 (2nd in tracks 1-4, 4th in tracks 5-8) 2 Adagio 7'23 Cello Sonata No. 2 Aino Hildebrandt, Viola 3 Scherzo: Allegro molto – Trio – 2 I Senza tempo 2'57 (1st in tracks 1-4, 2nd in tracks 5-8) 3 II Allegro 3'18 Allegro molto 5'08 4 III Largo 4'34 4 Introduction: Andante – Allegro 9'56 Martin Seemann, Violoncello st rd 5 IV Allegro 1'57 (1 in tracks 1-4, 3 in tracks 5-8) 6 V Lento 2'07 Carl Schuberth 1811 – 1863 Patrick Sepec, Violoncello nd 7 Musica nostalgica 3'16 String Octet E major, op. 23 (2 in tracks 1-4) for 4 Violins, 2 Violas and 2 Violoncellos Cello Sonata No. 1 Soloists of the Wrocław Baroque Orchestra 8 I Largo 3'22 5 Allegro moderato 10'43 Zbigniew Pilch, Violine -

26 March 2010 Page 1 of 22

Radio 3 Listings for 20 – 26 March 2010 Page 1 of 22 SATURDAY 20 MARCH 2010 Overture to Prince Igor Vancouver Symphony Orchestra, Bramwell Tovey (conductor) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00rd926) John Shea presents rarities, archive and concert recordings 05:12AM from Europe's leading broadcasters Poulenc, Francis (1899-1963) Quatre motets pour le temps de Noël 01:01AM Talinn Music High School Chamber Choir, Evi Eespere (director) Bach, Johann Sebastian (1685-1750) 05:22AM Molique, Bernhard (1802-1869) transcribed by Joseph Petric & Komm, Jesu, Komm! (BWV.229) Erica Goodman 01:11AM Six Songs without Words Fürchte dich nicht (BWV.228) Joseph Petric (accordion), Erica Goodman (harp) 01:21AM Jesu, meine Freude (BWV.227) 05:35AM 01:44AM Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1714-1788) Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied (BWV.225) Trio Sonata in A minor (Wq148) Les coucous bénévoles Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Sir John Eliot Gardiner (conductor) 05:48AM Goleminov, Marin (1908-2000) 02:03AM 5 Sketches for Strings (1952) Mendelssohn, Felix (1809-1847) Sofia Soloists Chamber Ensemble, Vassil Kazandjiev (conductor) Sonata for cello and piano No.1 in B flat major (Op.45) Diana Ozoliņa (cello), Lelde Paula (piano) 06:04AM Kraus, Joseph Martin (1756-1792) 02:26AM Sinfonie in E flat Beethoven, Ludwig van (1770-1827) Concerto Koln Symphony No.5 in C minor (Op.67) Venezuela Symphony Orchestra, Eduardo Chibás (conductor) 06:25AM Dvorak, Anton (1841-1904) 03:01AM Piano Trio No.4 in E Minor, Op.90 "Dumky" Bach, Johann Sebastian (1685-1750) Beaux Arts Trio. Brandenburg concerto No.5 (BWV.1050) in D major Per Flemstrøm (flute), Andrew Manze (violin), Andreas Staier (harpsichord), Risør Festival Strings SAT 07:00 Breakfast (b00rjxvs) Saturday - Martin Handley 03:22AM Mendelssohn, Felix (1809-1847) Breakfast on Radio 3 with Martin Handley. -

Ulrich Schiel

Base de Músicas de / Musikaufnahmen von / Recordings of ULRICH SCHIEL ([email protected]) Versão / Stand / Version: 16.10.2009 Chave compositor composição Intérpretes Rumänische Volksmusik für Panflöte ? Cembalo Abel, Carl Friedrich Sonate für Viola da Gamba Veronika Hampe - Gambe G-Dur Abel, K.F. Sonate für Viola da Gamba und BC Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für D.E. Lovell - Synth. Gitarrenduett Abel, K.F. Sonate K 176 für D.E. Lovell - Synth. Gitarrenduett Adson, J. Aria für Flöte und BC (P) 1969 Discos beverly LTDA conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Adson, J. Courtly masquino ayres 3 (P) 1968 rozenblit Tänze conjunto musikantiga de são paulo Alain, Jehan 2 Stücke für Orgel Marie-Claire Alain Albéniz, I. Estudio sem luz Alb Op.37 Albéniz, I. Danzas españolas Nr. ?? Tango Nr. 2: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Nr. 3: Pepe und Celin Romero - Gitarre Alb Op.47 Albéniz, I. Suite Española 5. Asturias Nr. 1 Granada: Pepe und Celin Romero - Git Nr. 1 Granada (5'20) : Julien Bream - Gitarre Albicastro, H. Concerto Op. 7 Nr. 6 F-Dur Süsdwestdeutsches Kammerorchester Pforzh Leitung: Paul Angerer Albinoni, T. Concerto a cinque Nr. 3 D- I Solisti Veneti Dur Albinoni, T. Concerto Grosso g-moll I Solisti Veneti Albinoni, T. Konzert für Oboe, Streicher Evald van Crift - Oboe und GB d-moll Op. 9 Nr.2 I Musici Albinoni, T. Konzert füt Trompete und Streichorchester Op. 7 Nr. 3 B-Dur Albinoni, T. Konzert füt Trompete und Wolfgang Basch - Trompete Streichorchester Op. 7 Nr. Wolfgang Rübsam - Orgel 6 AlbOp.2/3 Albinoni, T. -

![Werner-B01c[Erato-10CD]-BWV40.Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9195/werner-b01c-erato-10cd-bwv40-pdf-6939195.webp)

Werner-B01c[Erato-10CD]-BWV40.Pdf

Reinhold Barchet violin ' |acoba Muckel cello . Eva Hölderlin organ Producer: Michel Garcin . Recording engineer: Peter Willemoös Recording location: Ilsfeld, Germany, 1 96 1 Darzt ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes, BWV 40 For this there was sent us Christ the Saviour . C'est pour cela que le fik de Dieu est apparu Feria 2 Nativitatis Christi Cantata for the Second Day of Christmas . Pour le 2u'" jour de Noöl . Am 2. Weihnachtstag 07 1. [Coro]: Darzu ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes 4.40 Corni, oboi, violini, viola, basso continuo 08 2. Recitativo (Tenore): Das Wort ward Fleisch 1.28 Basso continuo 09 3. Choral (Coro): Die Sünd macht Leid 0.42 Corno, oboi, violini, viola, basso continuo 10 4. Aria (Basso): Höllische Schlange, wird dir nicht bange? 2.46 Oboi, violini, viola, basso continuo 11 5. Recitativo (Alto): Die Schlange, so im Paradies 1.08 Violini, viola, basso continuo LZ 6. Choral (Coro): Schüttle deinen Kopf und sprich 0.55 Corno, oboi, violini, viola, basso continuo 13 7 . Aria (Tenore): Christenkinder, freuet euch 4.29 Corni, oboi, basso continuo 14 8. Choral (Coro): )esu, nimm dich deiner Glieder l.l2 Corno, oboi, violini, viola, basso continuo Claudia Hellmann alto . Georg Ielden tenor . |akob Stämpfli bass Pierre Pierlot, |acques Chambon oboes . Hermann Baumann, Willy Rütten horns Iacoba Muckel cello . Eva Hölderlin organ Producer: Michel Garcin . Recording engineer: Peter Willemoäs Recording location: Heilbronn, Germany, June 1964 FritzWerner's Bach Renewed interest in Bach's cantatas and, to a lesser extent, his two great Passions and the Christmas Oratorio, was given sustained impetus in the early 1950s by the arrival of the LP. -

Hinweisdienst Musik

HINWEISDIENST MUSIK JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Hinweise für den Benutzer 1. Diese Onlinefassung ist kostenlos, jede Weiterverbreitung ist jedoch untersagt. 2. Nachgewiesen werden Tonaufnahmen, die im Deutschen Rundfunkarchiv an den Standorten Frankfurt a. M. (Ffm) oder Berlin vorhanden sind. 3. Aufnahmen einer Komposition sind durch Leerzeilen voneinander getrennt, wobei nachstehende Symbole Werk- und Aufnahmedaten differenzieren: Titel (Werktitel) einer Komposition, z.B. Oper, Sinfonie, Liederzyklus Gesamtaufnahme einer Komposition (bezugnehmend auf ), d.h. Nennung der Interpreten des mit markierten Werkes, z.B. einer Operngesamtaufnahme, vollständigen Aufnahme einer Sinfonie oder eines kompletten Liederzyklus' Teiltitel einer Komposition (Werkausschnitt), z.B. Bezeichnung einer Opernouvertüre oder einer einzelnen Arie, eines Sinfoniesatzes oder Liedes aus einem Liederzyklus Teilaufnahme eines Werkes (Aufnahme eines Ausschnitts bezugnehmend auf ), d.h. Nennung der jeweiligen Interpreten des mit markierten Werkausschnitts. 4. Aufnahmedaten, die nur annähernd ermittelt werden können, sind durch 'c' (circa), 'n' (nach) und 'v' (vor) bezeichnet (z.B. 1950c); ein der Jahreszahl hinzugefügtes 'p' weist darauf hin, daß lediglich das Veröffentlichungsdatum der Aufnahme zu ermitteln war (z.B. 1950p). Nicht ermittelbare Aufnahmedaten sind mit 'o.J.' (ohne Jahr), fehlende Zeitangaben mit 'o.A.' (ohne Angabe) gekennzeichnet. 5. Nachweise, die sich auf Bestände des ehemaligen Rundfunks der DDR am Standort Berlin des Deutschen Rundfunkarchivs beziehen (DRA Berlin), sind durch 'DRA Berlin' gekennzeichnet. Bestellungen dieser Aufnahmen richten Sie bitte an folgende Adresse: Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, Standort Berlin, Schallarchive, Rudower Chaussee 3, 12489 Berlin, Tel (030) 67764- 201, Fax: (030) 67764-200 Redaktionsschluß: 01.03.2000 Dieser Hinweisdienst wird vom Musik-Referat des Deutschen Rundfunkarchivs in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Standort Berlin zusammengestellt. Das Referat ist von Montag bis Freitag, jeweils von 8.30 bis 16.30 Uhr, zu erreichen. -

BACH CHOR.Indd

BACH DE MAINZ CORA ORAL BACH DE MAINZ Z CORAL BACH DE MA MAINZ CORAL BACH D RAL BACH DE MAINZ C BACH DE MAINZ CORA AL BACH DE MAINZ CO ADO ORQUESTRA FILA TRA FILARMÔNICA DA ICA DA RENÂNIA – PAL NIA – PALATINADO OR ÔNICA DA RENÂNIA – P OTTO RALF OTTO RAL RALF OTTO RALFRA OTTO TO RALF OTTO RALF O ALF OTTO RALF OTTO TO RALF OTTO RALF O A Telefônica aproxima você das pessoas e do melhor da cultura. Telefônica. Patrocinadora dos Concertos da Sociedade de Cultura Artística. TELEFONIA FIXA TELEFONIA CELULAR INTERNET SOLUÇÕES PARA EMPRESAS REDE DE TRANSMISSÃO INTERNACIONAL GUIA DE PRODUTOS E SERVIÇOS CONTACT CENTER PESQUISA E DESENVOLVIMENTO ENGENHARIA DE SEGURANÇA FUNDAÇÃO www.telefonica.com.br 14029_2CONCERT210X280.indd 1 3/20/06 12:19:39 PM CORAL BACH DE MAINZ ORQUESTRA FILARMÔNICA DA RENÂNIA – PALATINADO RALF OTTO REGÊNCIA HÉLÈNE GUILMETTE SOPRANO MECHTHILD GEORG MEZZO-SOPRANO DANIEL SANS TENOR KLAUS MERTENS BAIXO apoio patrocínio 14029_2CONCERT210X280.indd 1 3/20/06 12:19:39 PM CCORALORAL BBACHACH DDEE MMAINZAINZ o diversifi cado panorama da música coral da Alemanha, o Coral Bach de Mainz encontra-se há décadas entre os mais importantes ensembles vocais do país, pelo cultivo não apenas da N herança musical de Johann Sebastian Bach, como também de toda a música vocal erudita de alto nível de exigência escrita do século XVI até nossos dias. Em tempos recentes, o Coral Bach de Mainz vem registrando notável e amplo desenvolvimento, que se refl ete no crescente prestígio internacional de sua música. O Coral foi fundado em 1955 por Diethard Hellmann, discípulo de Günther Ramin, organista e regente do Coro da Igreja de São Tomás, em Leipzig.