Multiculturalism in the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morning Conditions Report Assiniboine River

Hydrologic Forecasting and Water Management July 22, 2020 Morning Conditions Report PROVISIONAL DATA http://www.gov.mb.ca/mit/floodinfo Assiniboine River - Tributaries Map Today's Conditions Change Today's Conditions Change ID LOCATION (Imperial) from (Metric) from Jul 21 Jul 21 FLOW LEVEL FLOW LEVEL (m) (cfs) (ft) (ft) (cms) (m) 1 Conjuring Creek near Russell 3 1,813.79 +0.03 0.1 552.84 +0.01 2 Smith Creek near Marchwell 0 1.22 -0.03 0.0 0.37 -0.01 3 Silver Creek near Binscarth 4 Cutarm Creek near Spy Hill 5 3.98 -0.01 0.1 1.21 0.00 5 Scissor Creek near Mcauley 2 2.96 +0.01 0.1 0.90 0.00 6 Birdtail Creek near Birtle 46 1,588.85 +0.22 1.3 484.28 +0.07 7 Arrow River near Arrow River 11 331.58 -0.03 0.3 101.07 -0.01 8 Gopher Creek near Virden 1 2.10 +0.06 0.0 0.64 +0.02 9 Oak River near Rivers 136 3.53 -0.05 3.8 1.08 -0.01 10 Baileys Creek near Oak Lake 0 337.50 -0.07 0.0 102.87 -0.02 11 Rolling River near Erickson 263 1,993.57 -0.11 7.4 607.64 -0.03 12 Little Saskatchewan River near Horod 102 26.76 -0.03 2.9 8.16 -0.01 13 Little Saskatchewan River near Minnedosa 512 1,715.84 -0.18 14.5 522.99 -0.05 14 Minnedosa Lake 1,682.47 +0.08 512.82 +0.02 15 Little Saskatchewan River above Rapid City Dam** 16 Rivers Reservoir* 1,538.18 -0.14 468.84 -0.04 17 Little Saskatchewan River near Rivers 1,819 1,484.00 -0.17 51.5 452.32 -0.05 18 Little Souris River near Brandon 19 4.96 -0.03 0.5 1.51 -0.01 19 Epinette Creek near Carberry 13 1.41 -0.01 0.4 0.43 0.00 20 Cypress River near Bruxelles 50 329.85 +0.64 1.4 100.54 +0.19 21 Sturgeon Creek at St. -

Geomorphic and Sedimentological History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin

Electronic Capture, 2008 The PDF file from which this document was printed was generated by scanning an original copy of the publication. Because the capture method used was 'Searchable Image (Exact)', it was not possible to proofread the resulting file to remove errors resulting from the capture process. Users should therefore verify critical information in an original copy of the publication. Recommended citation: J.T. Teller, L.H. Thorleifson, G. Matile and W.C. Brisbin, 1996. Sedimentology, Geomorphology and History of the Central Lake Agassiz Basin Field Trip Guidebook B2; Geological Association of CanadalMineralogical Association of Canada Annual Meeting, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 27-29, 1996. © 1996: This book, orportions ofit, may not be reproduced in any form without written permission ofthe Geological Association ofCanada, Winnipeg Section. Additional copies can be purchased from the Geological Association of Canada, Winnipeg Section. Details are given on the back cover. SEDIMENTOLOGY, GEOMORPHOLOGY, AND HISTORY OF THE CENTRAL LAKE AGASSIZ BASIN TABLE OF CONTENTS The Winnipeg Area 1 General Introduction to Lake Agassiz 4 DAY 1: Winnipeg to Delta Marsh Field Station 6 STOP 1: Delta Marsh Field Station. ...................... .. 10 DAY2: Delta Marsh Field Station to Brandon to Bruxelles, Return En Route to Next Stop 14 STOP 2: Campbell Beach Ridge at Arden 14 En Route to Next Stop 18 STOP 3: Distal Sediments of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 18 En Route to Next Stop 19 STOP 4: Flood Gravels at Head of Assiniboine Fan-Delta 24 En Route to Next Stop 24 STOP 5: Stott Buffalo Jump and Assiniboine Spillway - LUNCH 28 En Route to Next Stop 28 STOP 6: Spruce Woods 29 En Route to Next Stop 31 STOP 7: Bruxelles Glaciotectonic Cut 34 STOP 8: Pembina Spillway View 34 DAY 3: Delta Marsh Field Station to Latimer Gully to Winnipeg En Route to Next Stop 36 STOP 9: Distal Fan Sediment , 36 STOP 10: Valley Fill Sediments (Latimer Gully) 36 STOP 11: Deep Basin Landforms of Lake Agassiz 42 References Cited 49 Appendix "Review of Lake Agassiz history" (L.H. -

Water Quality Report

Central Assiniboine Watershed Integrated Watershed Management Plan - Water Quality Report October 2010 Central Assiniboine Watershed – Water Quality Report Water Quality Investigations and Routine Monitoring: This report provides an overview of the studies and routine monitoring which have been undertaken by Manitoba Water Stewardship’s Water Quality Management Section within the Central Assiniboine watershed. There are six long term water quality monitoring stations (1965 – 2009) within the Central Assiniboine Watershed. These include the Assiniboine, Souris and Cypress Rivers. There are also ten stations not part of the long term water quality monitoring program in which some data are available for alternate locations on the Assiniboine, Souris, and Little Saskatchewan Rivers. The Central Assiniboine River watershed area is characterized primarily by agricultural crop land, industry, urban and rural centres. All these land uses have the potential to negatively impact water quality, if not managed appropriately. Cropland can present water quality concerns in terms of fertilizer and pesticide runoff entering surface water. There are a number of large industrial operations in the Central Assiniboine Watershed, these present water quality concerns in terms of wastewater effluent and industrial runoff. Large centers and rural municipalities present water quality concerns in terms of wastewater treatment and effluent. The tributary of most concern in the Central Assiniboine watershed is the Assiniboine River, as it is the largest river in the watershed. The area surrounding the Assiniboine River is primarily agricultural production yielding a high potential for nutrient and bacteria loading. The Assiniboine River serves as the main drinking water source for many residents in this watershed. In addition, the Assiniboine River drains into Lake Winnipeg, and as such has been listed as a vulnerable water body in the Nutrient Management Regulation under the Water Protection Act. -

Manitoba's Flood of 2011

Manitoba’s Flood of 2011 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Steve Topping, P. Eng Executive Director, Regulatory and Operational Services Manitoba Water Stewardship September 13 , 2011 why was there so much water this year? why this flood was so different than 1997? was this a record-breaking year? Why was there so much water? • Antecedent Soil Moisture – April-October 2010 • Snow Moisture, Density and Depth •2010 was the 5th wettest September through February on record following the first wettest on record (2009) and 3rd wettest (2010). October 26-28th 2010 Why was there so much water? • Antecedent Soil Moisture – April-October 2010 • Snow Moisture, Density and Depth • Geography Snow Pack 2011 •Snowfall totals 75 to 90 inches, nearly double the climatological average. Newdale: 6-7 ft snow depth Why was there so much water? • Antecedent Soil Moisture – April-October 2010 • Snow Moisture, Density and Depth • Geography • Precipitation this Spring Why was there so much water? • Antecedent Soil Moisture – April-October 2010 • Snow Moisture, Density and Depth • Geography • Precipitation this Spring • Storm events at the wrong time •15th year of current wet cycle, resulting in very little storage in the soils Why was there so much water? • Antecedent Soil Moisture – April-October 2010 • Snow Moisture, Density and Depth • Geography • Precipitation this Spring • Storm events at the wrong time • Many watersheds flooding simultaneously May Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Pre-Flood Preparation • Supplies and Equipment • 3 amphibex icebreakers • 7 ice cutting machines • 3 amphibious ATVs • 3 million sandbags • 30,000 super sandbags • 3 sandbagging units (total of 6) • 24 heavy duty steamers (total of 61) • 43 km of cage barriers • 21 mobile pumps (total of 26) • 72 km of water filled barriers • and much more... -

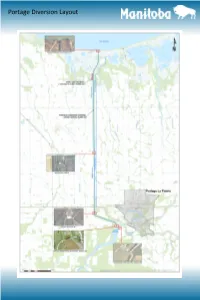

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects

Portage Diversion Layout Recent and Future Projects Assiniboine River Control Structure Public and worker safety improvements Completed in 2015 Works include fencing, signage, and safety boom Electrical and mechanical upgrades Ongoing Works include upgrades to 600V electrical distribution system, replacement of gate control system and mo- tor control center, new bulkhead gate hoist, new stand-by diesel generator fuel/piping system and new ex- terior diesel generator Portage Diversion East Outside Drain Reconstruction of 18 km of drain Completed in 2013 Replacement of culverts beneath three (3) railway crossings Completed in 2018 Recent and Future Projects Portage Diversion Outlet Structure Construction of temporary rock apron to stabilize outlet structure Completed in 2018 Conceptual Design for options to repair or replace structure Completed in 2018 Outlet structure major repair or replacement prioritized over next few years Portage Diversion Channel Removal of sedimentation within channel Completed in 2017 Groundwater/soil salinity study for the Portage Diversion Ongoing—commenced in 2016 Enhancement of East Dike north of PR 227 to address freeboard is- sues at design capacity of 25,000 cfs Proposed to commence in 2018 Multi-phase over the next couple of years Failsafe assessment and potential enhancement of West Dike to han- dle design capacity of 25,000 cfs Prioritized for future years—yet to be approved Historical Operating Guidelines Portage Diversion Operating Guidelines 1984 Red River Floodway Program of Operation Operation Objectives The Portage Diversion will be operated to meet these objectives: 1. To provide maximum benefits to the City of Winnipeg and areas along the Assiniboine River downstream of Portage la Prairie. -

Recent Developments Along the Assiniboine Corridor in Brandon

Prairie Perspectives 199 Down by the riverside: recent developments along the Assiniboine Corridor in Brandon G. Lee Repko and John Everitt Brandon University Abstract: In the past few years, the previously neglected Assiniboine River corridor within the city of Brandon has shown signs of significant change and development. These changes have largely been the result of a realization, by both city officials and community members, that an important local recreational resource has been neglected or ignored by the majority of Brandon’s inhabitants for many years. A series of public meetings sponsored by the city led to the acceptance of a plan for the riverbank and the formation of a not-for-profit group to bring planned changes into reality. In the past three years, pre-existing developments have been brought under the auspices of Riverbank Inc. and a series of new initiatives have been started. This paper briefly describes the past and contemporary development of Brandon’s Assiniboine river corridor. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to outline and report upon the development of the Assiniboine River Corridor by “Riverbank Inc.” Riverbank Inc. is a non-profit “arms length” organisation incorporated by the Province of Manitoba in 1994. The aim of the organisation is to develop the tract of land along the banks of the Assiniboine River within the city of Brandon as a recreational area for the city and its region, and as a possible ecological focal point for tourist activity within southwest Manitoba (Figure 1). The ongoing transformation of the river valley has the potential to be one of the major changes to the face of Brandon since its incorporation in 1882. -

Souris River Basin

The report of the International Garrison Diversion Study Board is bound in six volumes as follows: REPORT APPENDIX A - WATER QUALITY APPENDIX B - WATER QUANTITY APPENDIX C - BIOLOGY APPENDIX D - USES APPENDIX E - ENGINEERING APPENDIX D USES INTERNATIONAL JOINTCOMMISSION December 3, 1976 December 3, 1976 International Garrison Diversion StudyBoard Ottawa, Ontario, Canada Billings, Montana,United States Gentlemen: The Uses Committee is pleasedto submit herewith its final reportin accordance with the terms ofreference given to it by the International Garrison Diversione& Study Board. H.G. Mills, CanadianCo-chairman ,,I r " i / .I ,' . -,/'+.f?&&/p&<f T .A. Sandercock, Canafim Member United States Member & yjj 9-42. D.M. Tate, Cazadian Member E.W. Stevke,United States Member (ii) SUMMARY The Uses Committeehas analyzed the impacts of GDU onmajor water uses in the Red, Assiniboine and Souris river basins andon Lakes Winnipegand Manitoba. Water Uses includedin the analysis are: munici- pal,industrial, agricultural, rural domestic, recreational, fish and wildlife, andother. The analysisof GDU impacts is confined to usesin Canada.The effects upon theseimpacts of variousalternatives andmodi- ficationsto the authorized GDU project were alsoanalysed. The following sections summarize theresults of the Uses Committee'sanalysis. (a)Municipal Use (1) Increasedcosts of municipal water supplytreatment: Deteriorated water quality will require, as a minimum measure,that currentlyinstalled or planned water treatmentplants be operated at peakefficiency, producing the best quality of water ofwhich they are capable.This measure represents an increased cost of $59,000 annually. Constituentssuch as nitrates, sulfates andsodium would remain at post- GDU levels since reduction of theseparameters is beyond the capability ofcurrent treatment facilities. -

Present and Future Water Demand in the Qu'appelle River Basin

Present and Future Water Demand in the Qu’Appelle River Basin Suren Kulshreshtha Cecil Nagy Ana Bogdan With the Assistance of Albert Ugochukwu & Edward Knopf Department of Bioresource Policy, Business and Economics University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan A report prepared for SOUTH-CENTRAL ENTERPRISE REGION & SASKATCHEWAN WATERSHED AUTHORITY MOOSE JAW MAY 2012 Present and Future Water Demand in the Qu’Appelle River Basin Suren Kulshreshtha Professor Cecil Nagy Research Associate With the Assistance of Ana Bogdan Albert Ugochukwu Research Assistant & Edward Knopf Principal, Northern Bounty Trading, Regina Department of Bioresource Policy, Business and Economics University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan A report prepared for SOUTH-CENTRAL ENTERPRISE REGION (SCER) & SASKATCHEWAN WATERSHED AUTHORITY MOOSE JAW MAY 2012 Present and Future Water Use in the Qu’Appelle River Basin Kulshreshtha, Nagy & Bogdan May 2012 Page ii Present and Future Water Use in the Qu’Appelle River Basin Kulshreshtha, Nagy & Bogdan May 2012 Page ii Present and Future Water Use in the Qu’Appelle River Basin Kulshreshtha, Nagy & Bogdan Executive Summary Since water is a necessity for ecological functions, as well as for social and economic activities, its status as valuable commodity is an increasingly urgent concern for provincial planners. In the Qu’Appelle River Basin, the present water supplies are limited, and further expansion of water availability may be a costly measure. As the future economy in the basin increases, leading to population growth, competition for water could become even fiercer. Climate change may pose another threat to the region, partly due to reduced water supplies and increased demand for it. Development of sounder water management strategies may become a necessity. -

2.0 Native Land Use - Historical Period

2.0 NATIVE LAND USE - HISTORICAL PERIOD The first French explorers arrived in the Red River valley during the early 1730s. Their travels and encounters with the aboriginal populations were recorded in diaries and plotted on maps, and with that, recorded history began for the region known now as the Lake Winnipeg and Red River basins. Native Movements Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye records that there were three distinct groups present in this region during the 1730s and 1740s: the Cree, the Assiniboine, and the Sioux. The Cree were largely occupying the boreal forest areas of what is now northern and central Manitoba. The Assiniboine were living and hunting along the parkland transitional zone, particularly the ‘lower’ Red River and Assiniboine River valleys. The Sioux lived on the open plains in the region of the upper Red River valley, and west of the Red River in upper reaches of the Mississippi water system. Approximately 75 years later, when the first contingent of Selkirk Settlers arrived in 1812, the Assiniboine had completely vacated eastern Manitoba and moved off to the west and southwest, allowing the Ojibwa, or Saulteaux, to move in from the Lake of the Woods and Lake Superior regions. Farther to the south in the United States, the Ojibwa or Chippewa also had migrated westward, and had settled in the Red Lake region of what is now north central Minnesota. By this time some of the Sioux had given up the wooded eastern portions of their territory and dwelt exclusively on the open prairie west of the Red and south of the Pembina River. -

05260 Sask Watershed Report.Qxd:State of The

Saskatchewan Watershed Authority STATE OF THE WATERSHED REPORTING FRAMEWORK Monitoring and Assessment Branch Stewardship Division January 2006 Suite 420-2365 Albert Street Regina, Saskatchewan S4P 4K1 www.swa.ca Cover photos courtesy of (top-bottom): Saskatoon Tourism; Nature Saskatchewan; Saskatchewan Watershed Authority; Saskatchewan Watershed Authority; Wawryk Associates Ltd.; Ducks Unlimited Canada; Saskatchewan Watershed Authority; Nature Saskatchewan; and Saskatchewan Industry and Resources. Minister’s Message From the grasslands in the southwest to the Taiga Shield lakes of the north, we in Saskatchewan are blessed with richly diverse ecosystems. Over the past few decades, we have come to understand more about the nature of these ecosystems, and how we rely on them to support our economy and our overall quality of life. We have also increased our understanding of the responsibility we bear to assess, protect and improve our province’s environmental health, in balance with our social and economic priorities, for the good of present and future generations. We face a number of challenges regarding our water’s quality and availability. It is up to Saskatchewan people to determine how we will meet these challenges. The Saskatchewan government has taken a leadership role in assessing, protecting and managing our source waters by addressing them at the watershed level. The State of the Watershed Reporting Framework represents a critical step in understanding our relationship with Saskatchewan’s watersheds, as well as our role as stewards of our environment. For the first time in Saskatchewan, this framework will integrate the information collected by numerous provincial and federal agencies and present it in an easily understandable, technically sound report- card format. -

The Role of the Assiniboine River in the 1826 and 1852 Red River Floods

58 Prairie Perspectives The role of the Assiniboine River in the 1826 and 1852 Red River floods William F. Rannie, University of Winnipeg Abstract: Hydrologic conditions in the Assiniboine River basin during the extreme Red River floods of 1826 and 1852 are evaluated from historical sources. In both years, commentaries suggest that extreme floods also occurred in the Assiniboine, with the dominant source of water being the Souris River; in 1852 (and possibly 1826), the Qu’Appelle River discharge was also very high. It is concluded that the Assiniboine made large contributions to each of the epic historic floods, in contrast to its minor contribution to ‘natural’ flow in 1997. If reasonable allowance is made for the Assiniboine’s contribution to the estimated total historical flows of the Red, it is likely that the 1997 discharge of the Red alone (upstream of The Forks) was larger than in 1852, but still much smaller than in 1826. Key words: Assiniboine River, Red River, flood history, return period, 1826, 1852 Introduction The historic floods of 1826 and 1852 which devastated the Red River Settlement are the benchmarks against which modern floods in Winnipeg are judged. Until 1997, these floods had discharges far beyond any in the period of gauge records (Table 1), and even the third largest historic flood (in 1861) paled in comparison. The 1997 ‘natural’ (i.e., uncontrolled) discharge in Winnipeg almost equalled the normally-accepted value for the 1852 flood and precipitated planning to increase the level of Winnipeg’s protection to encompass a recurrence of 1826-magnitude or even larger floods. -

The Souris River Study Unit

The Souris River Study Unit.................................................................................11.1 Description of the Souris River Study Unit ......................................................11.1 Physiography ................................................................................................ 11.6 Drainage ....................................................................................................... 11.6 Climate.......................................................................................................... 11.7 Landforms and Soils..................................................................................... 11.8 Floodplains ............................................................................................... 11.8 Terraces .................................................................................................... 11.9 Valley Walls.............................................................................................. 11.9 Alluvial Fans........................................................................................... 11.10 Upland Plains ......................................................................................... 11.10 Flora and Fauna ......................................................................................... 11.10 Other Natural Resource Potential............................................................... 11.11 Overview of Previous Archeological Work .....................................................11.12 Inventory