The Prolonged QT Interval- a Frequently Unrecognized Abnormality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The QT Interval: How Long Is Too Long?

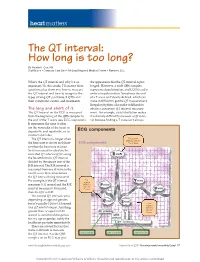

heart matters The QT interval: How long is too long? By Natalie K. Cox, RN Staff Nurse • Coronary Care Unit • McLeod Regional Medical Center • Florence, S.C. What’s the QT interval and why’s it so the appearance that the QT interval is pro- important? In this article, I’ll answer these longed. However, a wide QRS complex questions plus show you how to measure represents depolarization, and LQTS is a dis- the QT interval and how to recognize the order of repolarization. Sometimes the end types of long QT syndrome (LQTS) and of a T wave isn’t clearly defi ned, which can their symptoms, causes, and treatments. make it diffi cult to get the QT measurement. Irregular rhythms also make it diffi cult to The long and short of it obtain a consistent QT interval measure- The QT interval on the ECG is measured ment. For example, atrial fi brillation makes from the beginning of the QRS complex to it extremely diffi cult to measure a QT inter- the end of the T wave (see ECG components). val because fi nding a T wave isn’t always It represents the time it takes for the ventricles of the heart to depolarize and repolarize, or to ECG components contract and relax. The QT interval is longer when First positive deflection after the the heart rate is slower and short- ECG components P or Q wave er when the heart rate is faster. So it’s necessary to calculate the corrected QT interval (QTc) using the Bazett formula: QT interval divided by the square root of the R-R interval. -

Non Commercial Use Only

Cardiogenetics 2017; volume 7:6304 Sudden death in a young patient with atrial fibrillation Case Report Correspondence: María Angeles Espinosa Castro, Inherited Cardiovascular Disease A 22-year-old man suffered a sudden Program, Cardiology Department, Gregorio María Tamargo, cardiac arrest without previous symptoms Marañón Hospital, Dr. Esquerdo, 46, 28007, María Ángeles Espinosa, while he was at rest, waiting for a subway Madrid, Spain. Víctor Gómez-Carrillo, Miriam Juárez, train. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was Tel.: +34.91.586.82.90. immediately started using an Automated E-mail: [email protected] Francisco Fernández-Avilés, External Defibrillation that identified the Raquel Yotti Key words: KCNQ1; mutation; channelopa- presence of ventricular fibrillation and thy; sudden cardiac death; atrial fibrillation. Inherited Cardiovascular Disease delivered a shock. Return of spontaneous Program, Cardiology Department, circulation was achieved after three Contributions: MT, acquisition and interpreta- Gregorio Marañón Hospital, Madrid, attempts, being atrial fibrillation (AF) the tion of data for the work, ensuring that ques- Spain patient’s rhythm at this point (Figure 1). tions related to the accuracy or integrity of any He was admitted to our Cardiovascular part of the work is appropriately investigated Intensive Care Unit and therapeutic and resolved; MAE, conception of the work, hypothermia was performed over a period critical revision of the intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published, Abstract of 24 h. After completing hypothermia, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy rewarming, and another 24 h of controlled of any part of the work is appropriately inves- Sudden cardiac death (SCD) in young normothermia the patient awakened with no tigated and resolved; VG-C, acquisition and patients without structural heart disease is residual neurologic damage. -

Atrial Arrhythmia Triggering Electromechanical Dissociation And

EP CASE REPORT ....................................................................................................................................................... Atrial arrhythmia triggering electromechanical dissociation and ventricular fibrillation in a patient with atrial switch operation Nicolas Combes1,2,3*, Stefano Bartoletti1,2,Se´bastien Hascoet€ 3, Olivier Vahdat2, Franc¸ois Heitz2, and Victor Waldmann 4,5 1Electrophysiology Unit, Clinique Pasteur, Toulouse, France; 2Pediatric and Adult Congenital Heart Disease Department, Clinique Pasteur, 45, Avenue de Lombez, 31076 Toulouse, France; 3Pediatric and Adult Congenital Heart Disease Department, Hoˆpital Marie Lannelongue, Le Plessis-Robinson, France; 4Cardiology Department, Electrophysiology Unit, European Georges Pompidou Hospital, Paris, France; and 5Cardiology Department, Adult Congenital Heart Disease Unit, European Georges Pompidou Hospital, Paris, France * Corresponding author. Tel: 133 562213131; fax: 133 562211641. E-mail address: [email protected] A 26-year-old man with D- transposition of the great arteries (D-TGA) and pre- vious Mustard atrial switch surgery was referred for catheter ablation of a recur- rent symptomatic paroxys- mal atrial flutter. The arrhythmia was easily induci- ble (Figure 1A, cycle length 310 ms, rate 194 b.p.m.), with rapid conduction to the ventricles. While mapping flutter, simultaneous record- ing of endocardial signals and invasive blood pressure monitoring showed haemo- dynamic deterioration with intermittent electromechan- ical dissociation (Figure 1B) and then pulseless electrical activity (Figure 1C). After ini- tiation of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, several electric shocks failed to restore sinus rhythm and atrial flutter transitioned a few minutes later into ventricular tachy- cardia and then ventricular fibrillation (Figure 1D); this was ultimately terminated by defibrillation after an Figure 1 (A) Atrial flutter on 12-lead ECG induced by atrial bursts (240 ms), average ventricular response adrenaline bolus. -

Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: the Role of Multimodality Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features

diagnostics Review Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: The Role of Multimodality Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features Anna Giulia Pavon 1,2,*, Pierre Monney 1,2,3 and Juerg Schwitter 1,2,3 1 Cardiac MR Center (CRMC), Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (J.S.) 2 Cardiovascular Department, Division of Cardiology, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland 3 Faculty of Biology and Medicine, University of Lausanne (UniL), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-775-566-983 Abstract: Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) was first described in the 1960s, and it is usually a benign condition. However, a subtype of patients are known to have a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, the so called “arrhythmic MVP.” In recent years, several studies have been published to identify the most important clinical features to distinguish the benign form from the potentially lethal one in order to personalize patient’s treatment and follow-up. In this review, we specifically focused on red flags for increased arrhythmic risk to whom the cardiologist must be aware of while performing a cardiovascular imaging evaluation in patients with MVP. Keywords: mitral valve prolapse; arrhythmias; cardiovascular magnetic resonance Citation: Pavon, A.G.; Monney, P.; Schwitter, J. Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: The Role of Multimodality 1. Mitral Valve and Arrhythmias: A Long Story Short Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features. In the recent years, the scientific community has begun to pay increasing attention Diagnostics 2021, 11, 683. -

Long QT Syndrome: from Channels to Cardiac Arrhythmias

Long QT syndrome: from channels to cardiac arrhythmias Arthur J. Moss, Robert S. Kass J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2018-2024. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI25537. Review Series Long QT syndrome, a rare genetic disorder associated with life-threatening arrhythmias, has provided a wealth of information about fundamental mechanisms underlying human cardiac electrophysiology that has come about because of truly collaborative interactions between clinical and basic scientists. Our understanding of the mechanisms that control the critical plateau and repolarization phases of the human ventricular action potential has been raised to new levels through these studies, which have clarified the manner in which both potassium and sodium channels regulate this critical period of electrical activity. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/25537/pdf Review series Long QT syndrome: from channels to cardiac arrhythmias Arthur J. Moss1 and Robert S. Kass2 1Heart Research Follow-up Program, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York, USA. 2Department of Pharmacology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. Long QT syndrome, a rare genetic disorder associated with life-threatening arrhythmias, has provided a wealth of information about fundamental mechanisms underlying human cardiac electrophysiology that has come about because of truly collaborative interactions between clinical and basic scientists. Our understanding of the mecha- nisms that control the critical plateau and repolarization phases of the human ventricular action potential has been raised to new levels through these studies, which have clarified the manner in which both potassium and sodium channels regulate this critical period of electrical activity. -

Anemia and the QT Interval in Hypertensive Patients

2084 International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health Anemia and the QT interval in hypertensive patients Ioana Mozos 1*, Corina Serban 2, Rodica Mihaescu 3 1 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania 2 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania 3 1st Department of Internal Medicine, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania * Corresponding Author ; Email: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: A prolonged ECG QT interval duration and an increased QT dispersion (QTd) are predictors of sudden cardiac death. Anemia is known as a marker of adverse outcome in cardiovascular disease. Objective: The aim was to assess the relationship between anemia and QT intervals in hypertensive patients. Method: A total of 72 hypertensive patients underwent standard 12-lead ECG. QT intervals and QT dispersions were manually measured. Complete blood count was also assessed. Result: Linear regression analysis revealed significant associations between prolonged QTc and increased QTd and anemia and macrocytosis, respectively. Multiple regression analysis revealed a significant association between red cell distribution width (RDW) >15% and prolonged heart rate corrected maximal QT interval duration (QTc) and QT interval in lead DII (QTIIc). The most sensitive and specific predictor of prolonged QTc and QTIIc was anisocytosis. Anemia was the most sensitive predictor of -

Cardiac Arrest and Ventricular Fibrillation * a Method of Treatment by Electrical Shock

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.7.3.205 on 1 September 1952. Downloaded from Thorax (1952), 7, 205. CARDIAC ARREST AND VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION * A METHOD OF TREATMENT BY ELECTRICAL SHOCK BY I. K. R. MCMILLANt F. B. COCKETT, AND P. STYLES Froml the Departnment of Cardiology, tile Professorial Surgical Unit, and tile Departalzent of Phlysical Medicine, St. Thomlas's Hospital, London (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION APRIL 30, 1952) Cardiac arrest during operation is a subject of VENTRICULAR FIBRILLATION importance to all surgeons. During intra-thoracic The treatment of ventricular fibrillation bv operations cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrilla- electrical shock therapy is not new and was first tion can be differentiated by direct observation of tried experimentally in 1899 (Prevost and Battelli). the heart. In recent years this method has been extensively Ventricular fibrillation is an incoordinated type investigated in the United States and France of contraction which produces no useful beats. (Kouwenhoven and Kay, 1951; Johnson and The typical rippling movements of the ventricular Kirby, 1951 ; Santy and Marion, 1950). muscle are unmistakable when seen or felt with The treatment of ventricular fibrillation by the hand directly on the heart. The treatment of zlectrical shock gives encouraging results in the copyright. a heart that has stopped is cardiac massage and experimental animal, and may be a useful adjunct adequate oxygenation. The treatment of ventri- in the operating theatre during cardiac and general cular fibrillation which we recommend is, first, surgery. Under these conditions shock therapy massage to maintain the oxygen supply to the can be rapidly applied. Provided that adequate heart through the coronary arteries, followed oxygenation is maintained and direct cardiac mas- http://thorax.bmj.com/ rapidly by electrical shocking to restore normal sage promptly initiated and maintained, shock rhythm therapy can be applied without undue haste. -

Neurotransmitter Actions

Central University of South Bihar Panchanpur, Gaya, India E-Learning Resources Department of Biotechnology NB: These materials are taken/borrowed/modified/compiled from various resources like research articles and freely available internet websites, and are meant to be used solely for the teaching purpose in a public university, and for serving the needs of specified educational programmes. Dr. Jawaid Ahsan Assistant Professor Department of Biotechnology Central University of South Bihar (CUSB) Course Code: MSBTN2003E04 Course Name: Neuroscience Neurotransmitter Actions • Excitatory Action: – A neurotransmitter that puts a neuron closer to an action potential (facilitation) or causes an action potential • Inhibitory Action: – A neurotransmitter that moves a neuron further away from an action potential • Response of neuron: – Responds according to the sum of all the neurotransmitters received at one time Neurotransmitters • Acetylcholine • Monoamines – modified amino acids • Amino acids • Neuropeptides- short chains of amino acids • Depression: – Caused by the imbalances of neurotransmitters • Many drugs imitate neurotransmitters – Ex: Prozac, zoloft, alcohol, drugs, tobacco Release of Neurotransmitters • When an action potential reaches the end of an axon, Ca+ channels in the neuron open • Causes Ca+ to rush in – Cause the synaptic vesicles to fuse with the cell membrane – Release the neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft • After binding, neurotransmitters will either: – Be destroyed in the synaptic cleft OR – Taken back in to surrounding neurons (reuptake) Excitable cells: Definition: Refers to the ability of some cells to be electrically excited resulting in the generation of action potentials. Neurons, muscle cells (skeletal, cardiac, and smooth), and some endocrine cells (e.g., insulin- releasing pancreatic β cells) are excitable cells. -

The Refractory VF Arrest Patient: a Review of the Current Treatment

1/24/2018 The Refractory VF Arrest Patient: A Review of the Current Treatment Options Marc Conterato, MD, FACEP Office of the Medical Director North Memorial Health Ambulance Service DISCLOSURE STATEMENT • Board Member, MN Resuscitation Consortium - Images of any commercial devices or medications are for illustration purposes only. The inclusion of such images in this presentation does not imply endorsement of any specific device or company. 2 Objectives • Delineate Refractory Ventricular Fibrillation (RVF) • Recurrent VF versus Refractory VF • What is “Electrical Storm” • Current Pre-hospital treatments • Additional hospital treatments • Dual/Double Sequential Defibrillation • ECMO/ECLS-A New Hope? 3 1 1/24/2018 A Standard Scenario • 55 YOF collapses at stop light, and her car rolls into the car in front of her. Airbags do not deploy, and bystanders find her slumped over the steering wheel and pulseless. • First responder/bystanders start CPR, and deliver three AED shocks prior to EMS arrival. • On EMS arrival, a fourth shock is delivered, an IO and alternative airway placed. Automated CPR started. • Epinephrine 2 mg (total) and Amiodarone 300 mg given, and the patient remains in VF. • Patient downtime is now ~25 minutes, and repeat evaluation reveals persistent VF. 4 What are your options • Continue CPR for a total of 30 minutes with recurrent defibrillations, additional epinephrine, bicarbonate and Amiodarone? • “Load and Go” to the local hospital with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation? • “Load and Go” to the local CCL (Cardiac Cath Lab) hospital with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation, with possible PCI with ongoing CPR? • Call HEMS unit for transfer to CCL hospital, but can they continue effective CPR in the helicopter? • “Load and Go” to a ECMO/ECLS center with CPR enroute and continuing the resuscitation, on the basis they can accept the patient and continue resuscitation? 5 Defining the problem: What is recurrent versus refractory VF (RVF)? • Recurrent VF is a rhythm that terminates with cardioversion, but then recurs rapidly. -

Postural Heart Block*

Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.44.2.221 on 1 August 1980. Downloaded from Case reports Br Heart J 1980; 44: 221-3 Postural heart block* PETER E SEDA, JOHN H McANULTY, C JOE ANDERSON From the Department of Medicine, University of Oregon Health Sciences Center, Portland, Oregon, USA SUMMARY A patient presented with orthostatic dizziness and syncope caused by postural heart block. When the patient was supine, atrioventricular conduction was normal and he was asymptomatic; when he was standing he developed second degree type II block and symptoms. The left bundle-branch block on his electrocardiogram and intracardiac electrophysiological study findings suggest that this heart block occurred distal to the His bundle. Orthostatic symptoms are usually presumed to be secondary to an inappropriate distribution of intravascular volume or to autonomic nervous system abnormalities. As shown in this patient, these symptoms may be the result of orthostatic heart block. Ambulatory monitoring may be useful in patients with orthostatic neurological symptoms, particularly when conduction abnormalities are present on the electrocardiogram. Orthostatic neurological symptoms usually result minute and regular, and increased to 90 beats a from inadequate cerebral perfusion caused by minute with some irregularity when he was upright. disturbances of the autonomic nervous system,'-3 The carotid pulse was normal, and there were no ineffective or inappropriate shifts in volume carotid bruits. The cardiac impulse was normal. http://heart.bmj.com/ distribution,4 or drugs.5 We report a patient with The second heart sound was paradoxically split. orthostatic dizziness and syncope caused by inter- There was a grade 2/6 apical systolic murmur. -

Young Adults. Look for ST Elevation, Tall QRS Voltage, "Fishhook" Deformity at the J Point, and Prominent T Waves

EKG Abnormalities I. Early repolarization abnormality: A. A normal variant. Early repolarization is most often seen in healthy young adults. Look for ST elevation, tall QRS voltage, "fishhook" deformity at the J point, and prominent T waves. ST segment elevation is maximal in leads with tallest R waves. Note high take off of the ST segment in leads V4-6; the ST elevation in V2-3 is generally seen in most normal ECG's; the ST elevation in V2- 6 is concave upwards, another characteristic of this normal variant. Characteristics’ of early repolarization • notching or slurring of the terminal portion of the QRS wave • symmetric concordant T waves of large amplitude • relative temporal stability • most commonly presents in the precordial leads but often associated with it is less pronounced ST segment elevation in the limb leads To differentiate from anterior MI • the initial part of the ST segment is usually flat or convex upward in AMI • reciprocal ST depression may be present in AMI but not in early repolarization • ST segments in early repolarization are usually <2 mm (but have been reported up to 4 mm) To differentiate from pericarditis • the ST changes are more widespread in pericarditis • the T wave is normal in pericarditis • the ratio of the degree of ST elevation (measured using the PR segment as the baseline) to the height of the T wave is greater than 0.25 in V6 in pericarditis. 1 II. Acute Pericarditis: Stage 1 Pericarditis Changes A. Timing 1. Onset: Day 2-3 2. Duration: Up to 2 weeks B. Findings 1. -

The Relation Between Arterial Blood Pressure Variables and Ventricular Repolarization Parameters

860 International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health The relation between arterial blood pressure variables and ventricular repolarization parameters Ioana Mozos 1*, Corina Serban 2, Rodica Mihaescu 3 1 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania, [email protected] 2 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania 3 Department of Medical Semiology, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara, Romania ABSTRACT Introduction: Ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death risk are associated with prolonged electrocardiographic (ECG) QT and Tpeak-Tend intervals. Objective: To evaluate the influence of blood pressure variables on ventricular repolarization parameters, especially QT and Tpeak-Tend intervals. Method: Two groups of patients were enrolled in the study. The firs group included 77 patients, with essential hypertension, aged 62±12 years, 40% males. The control group included 56 patients, age and sex matched, with optimal, normal and high normal blood pressure. They underwent 12-lead ECG and ventricular repolarization parameters were assessed. QT intervals: QTmax (maximal QT interval duration), QTc (heart rate corrected QTmax), QTm (mean QT interval duration in all leads), QTIIc (heart rate corrected QT interval duration in lead DII), and T wave variables: T0e (maximal T wave duration), Tpe (maximal Tpeak-Tend interval) and Ta (maximal T wave amplitude) were manually measured. Arterial blood pressure variables: systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP), mean arterial (MAP) and pulse pressure (PP), were recorded. Result: SBP was 139±24 mmHg, DBP 86±13 mmHg, MAP 103±15 mmHg, PP 53±16 mmHg, QTmax 430±51 ms, QTc 474±48 ms and Tpe 100±26 ms in the hypertensive group.