Review Article Management of Atrial Fibrillation in Critically Ill Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The QT Interval: How Long Is Too Long?

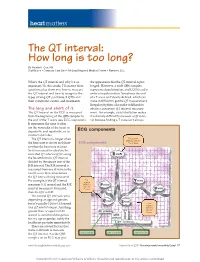

heart matters The QT interval: How long is too long? By Natalie K. Cox, RN Staff Nurse • Coronary Care Unit • McLeod Regional Medical Center • Florence, S.C. What’s the QT interval and why’s it so the appearance that the QT interval is pro- important? In this article, I’ll answer these longed. However, a wide QRS complex questions plus show you how to measure represents depolarization, and LQTS is a dis- the QT interval and how to recognize the order of repolarization. Sometimes the end types of long QT syndrome (LQTS) and of a T wave isn’t clearly defi ned, which can their symptoms, causes, and treatments. make it diffi cult to get the QT measurement. Irregular rhythms also make it diffi cult to The long and short of it obtain a consistent QT interval measure- The QT interval on the ECG is measured ment. For example, atrial fi brillation makes from the beginning of the QRS complex to it extremely diffi cult to measure a QT inter- the end of the T wave (see ECG components). val because fi nding a T wave isn’t always It represents the time it takes for the ventricles of the heart to depolarize and repolarize, or to ECG components contract and relax. The QT interval is longer when First positive deflection after the the heart rate is slower and short- ECG components P or Q wave er when the heart rate is faster. So it’s necessary to calculate the corrected QT interval (QTc) using the Bazett formula: QT interval divided by the square root of the R-R interval. -

Long QT Syndrome: from Channels to Cardiac Arrhythmias

Long QT syndrome: from channels to cardiac arrhythmias Arthur J. Moss, Robert S. Kass J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2018-2024. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI25537. Review Series Long QT syndrome, a rare genetic disorder associated with life-threatening arrhythmias, has provided a wealth of information about fundamental mechanisms underlying human cardiac electrophysiology that has come about because of truly collaborative interactions between clinical and basic scientists. Our understanding of the mechanisms that control the critical plateau and repolarization phases of the human ventricular action potential has been raised to new levels through these studies, which have clarified the manner in which both potassium and sodium channels regulate this critical period of electrical activity. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/25537/pdf Review series Long QT syndrome: from channels to cardiac arrhythmias Arthur J. Moss1 and Robert S. Kass2 1Heart Research Follow-up Program, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, New York, USA. 2Department of Pharmacology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York, USA. Long QT syndrome, a rare genetic disorder associated with life-threatening arrhythmias, has provided a wealth of information about fundamental mechanisms underlying human cardiac electrophysiology that has come about because of truly collaborative interactions between clinical and basic scientists. Our understanding of the mecha- nisms that control the critical plateau and repolarization phases of the human ventricular action potential has been raised to new levels through these studies, which have clarified the manner in which both potassium and sodium channels regulate this critical period of electrical activity. -

Anemia and the QT Interval in Hypertensive Patients

2084 International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health Anemia and the QT interval in hypertensive patients Ioana Mozos 1*, Corina Serban 2, Rodica Mihaescu 3 1 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania 2 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania 3 1st Department of Internal Medicine, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania * Corresponding Author ; Email: [email protected] Abstract Introduction: A prolonged ECG QT interval duration and an increased QT dispersion (QTd) are predictors of sudden cardiac death. Anemia is known as a marker of adverse outcome in cardiovascular disease. Objective: The aim was to assess the relationship between anemia and QT intervals in hypertensive patients. Method: A total of 72 hypertensive patients underwent standard 12-lead ECG. QT intervals and QT dispersions were manually measured. Complete blood count was also assessed. Result: Linear regression analysis revealed significant associations between prolonged QTc and increased QTd and anemia and macrocytosis, respectively. Multiple regression analysis revealed a significant association between red cell distribution width (RDW) >15% and prolonged heart rate corrected maximal QT interval duration (QTc) and QT interval in lead DII (QTIIc). The most sensitive and specific predictor of prolonged QTc and QTIIc was anisocytosis. Anemia was the most sensitive predictor of -

Young Adults. Look for ST Elevation, Tall QRS Voltage, "Fishhook" Deformity at the J Point, and Prominent T Waves

EKG Abnormalities I. Early repolarization abnormality: A. A normal variant. Early repolarization is most often seen in healthy young adults. Look for ST elevation, tall QRS voltage, "fishhook" deformity at the J point, and prominent T waves. ST segment elevation is maximal in leads with tallest R waves. Note high take off of the ST segment in leads V4-6; the ST elevation in V2-3 is generally seen in most normal ECG's; the ST elevation in V2- 6 is concave upwards, another characteristic of this normal variant. Characteristics’ of early repolarization • notching or slurring of the terminal portion of the QRS wave • symmetric concordant T waves of large amplitude • relative temporal stability • most commonly presents in the precordial leads but often associated with it is less pronounced ST segment elevation in the limb leads To differentiate from anterior MI • the initial part of the ST segment is usually flat or convex upward in AMI • reciprocal ST depression may be present in AMI but not in early repolarization • ST segments in early repolarization are usually <2 mm (but have been reported up to 4 mm) To differentiate from pericarditis • the ST changes are more widespread in pericarditis • the T wave is normal in pericarditis • the ratio of the degree of ST elevation (measured using the PR segment as the baseline) to the height of the T wave is greater than 0.25 in V6 in pericarditis. 1 II. Acute Pericarditis: Stage 1 Pericarditis Changes A. Timing 1. Onset: Day 2-3 2. Duration: Up to 2 weeks B. Findings 1. -

The Relation Between Arterial Blood Pressure Variables and Ventricular Repolarization Parameters

860 International Journal of Collaborative Research on Internal Medicine & Public Health The relation between arterial blood pressure variables and ventricular repolarization parameters Ioana Mozos 1*, Corina Serban 2, Rodica Mihaescu 3 1 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania, [email protected] 2 Department of Functional Sciences, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania 3 Department of Medical Semiology, “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara, Romania ABSTRACT Introduction: Ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death risk are associated with prolonged electrocardiographic (ECG) QT and Tpeak-Tend intervals. Objective: To evaluate the influence of blood pressure variables on ventricular repolarization parameters, especially QT and Tpeak-Tend intervals. Method: Two groups of patients were enrolled in the study. The firs group included 77 patients, with essential hypertension, aged 62±12 years, 40% males. The control group included 56 patients, age and sex matched, with optimal, normal and high normal blood pressure. They underwent 12-lead ECG and ventricular repolarization parameters were assessed. QT intervals: QTmax (maximal QT interval duration), QTc (heart rate corrected QTmax), QTm (mean QT interval duration in all leads), QTIIc (heart rate corrected QT interval duration in lead DII), and T wave variables: T0e (maximal T wave duration), Tpe (maximal Tpeak-Tend interval) and Ta (maximal T wave amplitude) were manually measured. Arterial blood pressure variables: systolic (SBP), diastolic (DBP), mean arterial (MAP) and pulse pressure (PP), were recorded. Result: SBP was 139±24 mmHg, DBP 86±13 mmHg, MAP 103±15 mmHg, PP 53±16 mmHg, QTmax 430±51 ms, QTc 474±48 ms and Tpe 100±26 ms in the hypertensive group. -

The Effect of Esmolol on Corrected-QT Interval, Corrected-QT

Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2015;65(1):34---40 REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE Official Publication of the Brazilian Society of Anesthesiology ANESTESIOLOGIA www.sba.com.br SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE The effect of esmolol on corrected-QT interval, corrected-QT interval dispersion changes seen during anesthesia induction in hypertensive patients taking an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor ∗ Zahit C¸eker, Suna Akın Takmaz , Bülent Baltaci, Hülya Bas¸ar Department of Anesthesiolgy and Reanimation, Ankara Training and Research Hospital, Ministry of Health, Ankara, Turkey Received 16 January 2014; accepted 19 March 2014 Available online 1 May 2014 KEYWORDS Abstract Esmolol; Background and objectives: The importance of minimizing the exaggerated sympatho- adrenergic responses and QT interval and QT interval dispersion changes that may develop QT interval; due to laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation during anesthesia induction in the hypertensive QT dispersion; patients is clear. Esmolol decreases the hemodynamic response to laryngoscopy and intubation. ACE inhibitor However, the effect of esmolol in decreasing the prolonged QT interval and QT interval disper- sion as induced by laryngoscopy and intubation is controversial. We investigated the effect of esmolol on the hemodynamic, and corrected-QT interval and corrected-QT interval dispersion changes seen during anesthesia induction in hypertensive patients using angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Methods: 60 ASA I---II patients, with essential hypertension using angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors were included in the study. The esmolol group received esmolol at a bolus dose of 500 mcg/kg followed by a 100 mcg/kg/min infusion which continued until the 4th min after intubation. The control group received 0.9% saline similar to the esmolol group. -

Mechanism of Drug-Induced Qt Interval Prolongation

ABSTRACT Torsades de pointes (TdP) is a polymorphic ventricular tachycardia characterized by a distinctive pattern of undulating QRS complexes that twist around the isoelectric line. TdP is usually self-terminating or can subsequently degenerate into ventricular fibrillation, syncope, and sudden death. TdP has been associated with QT interval prolongation of the electrocardiogram; therefore, the QT interval has come to be recognized as a surrogate marker for the risk of TdP. International guidelines have been developed to harmonize both the preclinical and clinical studies for the evaluation of drug-induced TdP. However, currently preclinical in vitro and in vivo methods as well as biomarkers for proarrhythmias have been imperfect in predicting drug-induced TdP in humans. It is clear that relevant biomarkers together with appropriate models are needed to assess the arrhythmic risk of new chemical entities. The goal of the present dissertation is to create rabbit with myocardial failing heart as an in vivo animal model to predict TdP in humans and to determine mechanism(s) underlying TdP in this model. Electrocardiograms were recorded from bipolar transthoracic leads in 7 conscious healthy rabbits previously trained to rest quietly in slings. The RR and QT relationship, ii QT=2.4RR0.72 (r2=0.79, p < 0.001) was obtained by slowed the heart rate with 2.0 mg/kg zatebradine, and the algorithm for removing effect of heart rate on QT is QTc = QT/(RR)0.72. QTc lengthened significantly in all conscious rabbits given intravenous cisapride, dofetilide or haloperidol (p < 0.05), and QTc did not change with DMSO (vehicle control), propranolol or enalaprilat. -

Hyperhomocysteinemia Alters Sinoatrial and Atrioventricular Nodal Function : Role of the Cardiac NMDA Receptor

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2012 Hyperhomocysteinemia alters sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodal function : role of the cardiac NMDA receptor. Chirag V. Soni University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Soni, Chirag V., "Hyperhomocysteinemia alters sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodal function : role of the cardiac NMDA receptor." (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1360. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1360 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HYPERHOMOCYSTEINEMIA ALTERS SINOATRIAL AND ATRIOVENTRICULAR NODAL FUNCTION: ROLE OF THE CARDIAC NMDA RECEPTOR By Chi rag V. Soni B.A., Northwestern University, 1999 M.S., University of Louisville, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Medicine of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physiology and Biophysics University of Louisville Louisville, KY December 2012 Copyright 2012 by Chirag V. Soni All rights reserved HYPERHOMOCYSTEINEMIA ALTERS SINOATRIAL AND ATRIOVENTRICULAR NODAL FUNCTION: ROLE OF THE CARDIAC NMDA RECEPTOR By Chirag V. Soni B.A., Northwestern University, 1999 M.S., University of Louisville, 2005 A Dissertation Approved on August 27th, 2012 By the Following Dissertation Committee: Claudio Maldonado, Ph.D., Mentor Suresh Tyagi, Ph.D. -

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

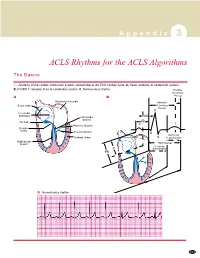

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

Dysrhythmias

CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS DYSRHYTHMIAS I. BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CARDIAC CONDUCTION DISTURBANCES A. Standard ECG and rhythm strips 1. Recordings are obtained at a paper speed of 25 mm/sec. 2. The vertical axis measures distance; the smallest divisions are 1 mm ×1 mm. 3. The horizontal axis measures time; each small division is 0.04 sec/mm. B. Normal morphology Courtesy of Dr. Michael McCrea 1. P wave = atrial depolarization a. Upright in leads I, II, III, aVL, and aVF; inverted in lead aVR b. Measures <0.10 seconds wide and <3 mm high c. Normal PR interval is 0.12–0.20 seconds. 2. QRS complex = ventricular depolarization a. Measures 0.06-0.10 seconds wide b. Q wave (1) <0.04 seconds wide and <3 mm deep (2) Abnormal if it is >3 mm deep or >1/3 of the QRS complex. c. R wave ≤7.5 mm high 3. QT interval varies with rate and sex but is usually 0.33–0.42 seconds; at normal heart rates, it is normally <1/2 the preceding RR interval. 4. T wave = ventricular repolarization a. Upright in leads I, II, V3–V6; inverted in aVR b. Slightly rounded and asymmetric in configuration c. Measures ≤5 mm high in limb leads and ≤10 mm high in the chest leads 5. U wave = a ventricular afterpotential a. Any deflection after the T wave (usually low voltage) b. Same polarity as the T wave c. Most easily detected in lead V3 d. Can be a normal component of the ECG e. Prominent U waves may indicate one of the following: (1) Hypokalemia (<3 mEq/L) (2) Hypercalcemia (3) Therapy with digitalis, phenothiazines, quinidine, epinephrine, inotropic agents, or amiodarone (4) Thyrotoxicosis f. -

Heart Rate-Corrected QT Interval Prolongation Predicts Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Black and White Middle-Aged Men and Women the ARIC Study Jacqueline M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Journal of the American College of Cardiology providedVol. by Elsevier 43, No. - 4,Publisher 2004 Connector © 2004 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation ISSN 0735-1097/04/$30.00 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2003.09.040 Risk Predictors and Coronary Disease Heart Rate-Corrected QT Interval Prolongation Predicts Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Black and White Middle-Aged Men and Women The ARIC Study Jacqueline M. Dekker, PHD,*† Richard S. Crow, MD,‡ Peter J. Hannan, MSTAT,‡ Evert G. Schouten, MD, PHD,* Aaron R. Folsom, MD, MPH‡ Wageningen and Amsterdam, the Netherlands; and Minneapolis, Minnesota OBJECTIVES We aimed to study the predictive value of heart rate-corrected QT interval (QTc) for incident coronary heart disease (CHD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality in the black and white general population, and to validate various QT measurements. BACKGROUND QTc prolongation is associated with higher risk of mortality in cardiac patients and in the general population. Little is known about the association with incident CHD. No previous studies included black populations. METHODS We studied the predictive value of QTc prolongation in a prospective population study of 14,548 black and white men and women, age 45 to 64 year. QT was determined by the NOVACODE program in the digital electrocardiogram recorded at baseline. RESULTS In quintiles of QTc, cardiovascular risk profile deteriorated with longer QTc, and risk of CHD and CVD mortality increased. The high risk in the upper quintile was mostly explained by the 10% with the longest QTc. -

Genetic and Molecular Aspects of Drug-Induced QT Interval Prolongation

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Genetic and Molecular Aspects of Drug-Induced QT Interval Prolongation Daniela Baracaldo-Santamaría 1 , Kevin Llinás-Caballero 2,3 , Julián Miguel Corso-Ramirez 1 , Carlos Martín Restrepo 2 , Camilo Alberto Dominguez-Dominguez 1 , Dora Janeth Fonseca-Mendoza 2 and Carlos Alberto Calderon-Ospina 2,* 1 School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá 111221, Colombia; [email protected] (D.B.-S.); [email protected] (J.M.C.-R.); [email protected] (C.A.D.-D.) 2 GENIUROS Research Group, Center for Research in Genetics and Genomics (CIGGUR), School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, Bogotá 111221, Colombia; [email protected] (K.L.-C.); [email protected] (C.M.R.); [email protected] (D.J.F.-M.) 3 Institute for Immunological Research, University of Cartagena, Cartagena 130014, Colombia * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +57-1-2970200 (ext. 3318) Abstract: Long QT syndromes can be either acquired or congenital. Drugs are one of the many etiologies that may induce acquired long QT syndrome. In fact, many drugs frequently used in the clinical setting are a known risk factor for a prolonged QT interval, thus increasing the chances of developing torsade de pointes. The molecular mechanisms involved in the prolongation of the QT interval are common to most medications. However, there is considerable inter-individual variability Citation: Baracaldo-Santamaría, D.; Llinás-Caballero, K.; Corso-Ramirez, in drug response, thus making the application of personalized medicine a relevant aspect in long QT J.M.; Restrepo, C.M.; syndrome, in order to evaluate the risk of every individual from a pharmacogenetic standpoint.