Japan's Underclass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study on the Construction Mechanism of Urban Public Space in Modern Shanghai and Yokohama

The 18th International Planning History Society Conference - Yokohama, July 2018 A Comparative Study on the Construction Mechanism of Urban Public Space in Modern Shanghai and Yokohama Wang Yan*, Zhou Xiangpin**, Zhou Teng*** * PhD, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tongji University, [email protected] ** Assistant Professor, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tongji University, [email protected] ***Master Student, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tongji University, [email protected] In the 19th century, after experienced the " open port " and " port opening ", Shanghai and Yokohama opened to the world, became the important ports for Europe and the United States in East Asia. In the view of different historical geography, background and management, Shanghai and Yokohama show different development processes and characteristics. On the basis of briefing the modern urban and social background of Shanghai and Yokohama, this paper analyses the similarities and differences from the aspects of urban forms, architecture scene, park space, based on these, try to conclude the reasons from the system policy, concept cognition, and the management feedback, supposes to place the studies in a broader perspective, understands the construction mechanism of the Modern East Asian cities. Keywords: Modern, Yokohama, Shanghai, Urban Public Space Introduction The book Amherst Tour 1832 is regarded to be the earliest western record of modern Shanghai. Maclellan (1899), Montalto (1909), Lanning and Couling (1921), Fredet and Jean (1929), Pott (1928), Miller (1937), Hauser (1940) and Murphey (1953) also explained the modern Shanghai in their own aspects. Since 1930, Chinese scholars began to study modern ShanghaiYazi Liu wrote the Shanghai History and the Shanghai History Series, Zhenchang Tang wrote the Shanghai History in 1988. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Culture and Tourism Bureau

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Culture and Tourism Bureau (relocating in June 2020 to 50-10 Honcho 6-chome, Naka-ku, Yokohama) TEL:(+81)- 45-671-4123 Web:www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/city-info/yokohamashi/org/bunko/ City of Yokohama Culture and Tourism Bureau E-mail:[email protected] Annual Report 2018 Cover photo: The SKY GARDEN (Observatory of the Landmark Tower Yokohama) Introduction Introduction Highlights See a city bursting with life! Introduction Taking things to the next level Dance Dance Dance @ YOKOHAMA 2018 Fiscal 2018 marked the start of Yokohama’s new Mid-term 4-Year Plan (2018-2021) and we launched of a variety of initiatives designed to Dance Dance Dance @ YOKOHAMA 2018 was held for the third time as a dance Highlights make the city more attractive in readiness for the approaching Rugby World Cup 2019TM and Tokyo 2020 Olympic and Paralympic festival that is staged in the streets of Yokohama itself. A diverse program of 260 events Games. We are also pursuing several projects from the perspective of raising a new generation of citizens and promoting social inclusion were performed, including outdoor stage performances taking full advantage of (“Creative Children” and “Creative Inclusion”) to maximize the city’s creative potential. We provided opportunities to enjoy culture and Yokohamaʼs unique cityscape, and other events that were held at open spaces such as the arts at close hand throughout the city by, for example, staging the “Dance Dance Dance @ YOKOHAMA 2018” dance festival, commercial facilities and station plazas. In particular, events hosted or co-hosted by the Yokohama Arts Festival Executive Committee attracted some 1,020,000 visitors. -

FTTP2018 the 2Nd Foreign Technical Training Programme at YNU for Anna University and Government Engineering Colleges of Tamil Nadu

FTTP2018 The 2nd Foreign Technical Training Programme at YNU for Anna University and Government Engineering Colleges of Tamil Nadu June 17 – July 3, 2018, Yokohama, Japan Science and engineering student studying at the state of Tamil Nadu in the southern part of India visit Yokohama National University and students learn about the current situation of Japanese culture, research development in university and private science and technology development by students visiting lectures, laboratory visits and companies mainly in Yokohama city for 2 weeks. Contents Preface Schedule of the Foreign Technical Training Programme(FTTP) Lectures Student Exchange Poster Session Industrial Visits and Cultural Excursions Campus information, Map, Access Appendix Emergency Contact Associate Professor Kazuho Nakamura TEL 045-339-3980 Mobile 090-4618-8858 E-mail [email protected] Preface Welcome to Yokohama National University! In 2017 the honorable chief minister of Tamil Nadu had announced under Rule 110 in connection with Foreign Technical Training Programme (FTTP) for 100 students (50 students of Anna University accompanying with staff and 50 students from Government Engineering Colleges of Tamil Nadu accompanying with staff) at an estimated expenditure of Rs. 150 Lakhs every year. The top scorer of each core branches in Anna University and Government Engineering Colleges of Tamil Nadu are eligible to participate in FTTP. Last year 15 students selected from Electronics & Communication Engineering and 9 students selected from the faculty of Technology attended the 1st FTTP at Yokohama National University (YNU). It was a great honor for us. This year we are very happy to hear the request of the 2nd FTTP at YNU. -

Japan Joint Nuclear Energy Action Plan

United States -Japan Joint Nuclear Energy Action Plan 1. Introduction 1.1 Background and Objective President Bush of the United States and Prime Minister Koizumi of Japan have both stated their strong support for the contribution of nuclear power to energy security and the global environment. Japan was the first nation to endorse President Bush's Global Nuclear Energy Partnership. During the June 29,2006 meeting between President Bush and Prime Minister Koizumi, "We discussed research and development that will help speed up fnt breeder reactors and new types of reprocessing so that we cmt help deal with the cost of globalization when it comes to energy; make ourselves more secure, economicallyIas well n make us less dependent on hycirocmbons ..... " (I) "U.S.Japanpmtnershipstamis n one of the most accomplished bilateral relationship in history. They reviewed with great sarisfaction the broadened and enhunced cooperuh'on achieved in the alliance Mder their joint steward~hip, and together heralded a new U.S.Japan Alliance of Glohal Cooperation for the 21st Cenhuy. " (2) On January 9,2007, Samuel W. Bodman, Secretary of Energy of the United States, and Akira Amari, Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan, met in Washingtun, D.C. to review their current and prospective cooperative activities in the energy field. The Secretary and the Minister agreed that both sides are committed to collaboration on the various aspects of the civilian nuclear fuel cycle. They agreed that the United States and Japan would jointly develop a civil nuclear energy action plan that would support such collaboration. Tbe plan would focus on: (a) research and development activities under the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership initiative that will build upon the significant civilian nuclear energy technical cooperation already underway; (b) collaboration on policies and programs that support the cowtrwtion of new nuclear power plants; and (c) regulatory and nonproliferation-related exchanges. -

The Trilateral Commission

THE TRILATERAL COMMISSION MARCH 2009 *Executive Committee PETER SUTHERLAND JOSEPH S. NYE, JR. YOTARO KOBAYASHI European Chairman North American Chairman Pacific Asian Chairman HERVÉ DE CARMOY ALLAN E. GOTLIEB HAN SUNG-JOO European North American Pacific Asian Deputy Chairman Deputy Chairman Deputy Chairman ANDRZEJ OLECHOWSKI LORENZO H. ZAMBRANO SHIJURO OGATA European North American Pacific Asian Deputy Chairman Deputy Chairman Deputy Chairman DAVID ROCKEFELLER Founder and Honorary Chairman GEORGES BERTHOIN PAUL A. VOLCKER OTTO GRAF LAMBSDORFF European Honorary Chairman North American Honorary Chairman European Honorary Chairman *** PAUL RÉVAY MICHAEL J. O'NEIL TADASHI YAMAMOTO European Director North American Director Pacific Asian Director EUROPEAN GROUP Urban Ahlin, Member of the Swedish Parliament and Deputy Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Stockholm *Edmond Alphandéry, Chairman, CNP Assurances, Paris; former Chairman, Electricité de France (EDF); former Minister of the Economy and Finance Jacques Andréani, Ambassadeur de France, Paris; former Ambassador to the United States Jorge Armindo, President and Chief Executive Officer, Amorim Turismo, Lisbon Jerzy Baczynski, Editor-in-Chief, Polityka, Warsaw Patricia Barbizet, Chief Executive Officer and Member of the Board of Directors, Artémis Group, Paris Estela Barbot, Director, AGA; Director, Bank Santander Negocios; Member of the General Council, AEP -- Portuguese Business Association, Porto; General Honorary Consul of Guatemala, Lisbon *Erik Belfrage, Senior Vice President, -

History of City Planning in the City of Yokohama

History of City Planning in the City of Yokohama City Planning Division, Planning Department, Housing & Architecture Bureau, City of Yokohama 1. Overview of the City of Yokohama (1) Location/geographical features Yokohama is located in eastern Kanagawa Prefecture at 139° 27’ 53” to 139° 43’ 31” East longitude and 35° 18’ 45” to 35° 35’ 34” North latitude. It faces Tokyo Bay to the east and the cities of Yamato, Fujisawa, and Machida (Tokyo) to the west. The city of Kawasaki lies to the north, and the cities of Kamakura, Zushi, and Yokosuka are to the south. Yokohama encompasses the largest area of all municipalities in the prefecture and is the prefectural capital. There are also rolling hills running north-south in the city’s center. In the north is the southernmost end of Tama Hills, and in the south is the northernmost end of Miura Hills that extends to the Miura Peninsula. A flat tableland stretches east-west in the hills, while narrow terraces are partially formed along the rivers running through the tableland and hills. Furthermore, valley plains are found in the river areas and coastal lowland on the coastal areas. Reclaimed land has been constructed along the coast so that the shoreline is almost entirely modified into manmade topography. (2) Municipal area/population trends The municipality was formed in 1889 and established the City of Yokohama. Thereafter, the municipal area was expanded, a ward system enforced, and new wards created, resulting in the current 18 wards (administrative divisions) and an area of 435.43km2. Although the population considerably declined after WWII, it increased by nearly 100,000 each year during the period of high economic growth. -

Chinatown's Annual Events 2021

26 TUNG FAT NEW PASTRY SHOP 同發新館 売店 681-8806 25 ROUROU ROUROU 650-5466 Yokohama ALL-YOU-CAN-EAT RESTAURANT E-2 C-5 TUNG FAT PASTRY SHOP 同發新売店 681-2976 RYU MAINSTREET SHOP 龍 大通り本店 227-7688 2 Chinatown’s 1 BEIJINROASTDUCK SPECIAL STORE 北京炒栲鴨店 305-6677 27 26 2 The History of Yokohama Chinatown Annual Events 2021 D-3 D-2 E-2 0 WANGFUJING HONTEN 王府井本店 641-1595 RYU DRAGON SHOP 龍 関帝廟通り青龍店 640-0788 0 2021 CHUKAGAI DAIHANTEN 中華街大飯店 227-9888 28 27 2 2 E-2 E-4 2 In 1859, after the port of Yokohama was opened to international trade, Jan. ■ 2021 Feb. Shunsetsu Mar. Toka May Jun. Jul. B-3 1 29 YOKOHAMAZAZIPAI 横浜炸鶏排 512-3263 28 RYU PHOENIX SHOP 龍 市場通り朱雀店 651-1977 1 Western merchants began to come to Yokohama. They brought with -Feb.28 (Sun.) 3 DAISOGEN 大草原 680-5558 F-5 D-3 . them Chinese assistants to act as interpreters to facilitate their B-2 . 0 Brilliant coloring through illuminations and lanterns 30 YOKOHAMAZAZIPAI ICHIBADORITEN 横濱炸鶏排 市場通り店 681-2052 29 RYUKI 龍起 663-9818 0 negotiations with the Japanese. The Chinese played the role of 4 HINCHINKAKU 品珍閣 681-7828 D-4 C-4 6 D-4 6 SEICHOEN 清朝園 651-7474 . middlemen in the tea and silk trade as interpreters, money HONG KONG RESTAURANT 香港大飯店 212-1818 30 . 0 5 B-3 0 exchangers etc.. ■ D-2 1 Spring Festival Countdown 1 In those days, the Chinese also took jobs as chefs (cooking knife), 6 HOUTENKAKU 鵬天閣 633-3598 CHINESE GROCERY・CHINESE TEA 31 SEIKA 盛華 681-6847 Feb.11(Thu.) (to be scheduled) D-3 D-3 tailors (scissors), and barbers (haircutting scissors), known to be San YOKOHAMA MASOBYO 7 KAFUKUHANTEN 華福飯店 212-1898 1 CHINESE SUPER MARKET 中国貿易公司 中華街本店 662-2899 32 SHOUHOU 照宝 681-0234 21 B-3 D-2 21 ba dao (meaning“the three knives”). -

Handout(PDF:237KB)

Innovator Japan ~~JapanJapan’s’s newnew sciencescience andand technologytechnology strategystrategy~~ IwaoIwao MatsudaMatsuda MinisterMinister ofof StateState forfor ScienceScience andand TechnologyTechnology PolicyPolicy MayMay 3,3, 2006,2006, WSPAWSPA The Basics of Japan's Science and Technology Policy The Council for Science and Technology Policy Members (Meets monthly) Name Position, title, etc. Junichiro Koizumi Prime Minister Major Events in Science and Shinzo Abe Chief Cabinet Secretary Technology Administration Minister of State for Science and Iwao Matsuda Technology Policy • 1995 Science and Minister for Internal Affairs and Cabinet Heizo Takenaka Communications Technology Basic Law Members Sadakazu Tanigaki Minister of Finance enacted Minister of Education, Culture, Kenji Kosaka Sports, Science and Technology • 1996–2000 1st Science Minister of Economy, Trade and Toshihiro Nikai Industry and Technology Basic Plan Full-time member (Professor Hiroyuki Abe • 2001 Cabinet Office and Emeritus, Tohoku University) Full-time member (Visiting Professor, Taizo Yakushiji Council for Science and Keio University) Tadamitsu Full-time member (Visiting Professor, Technology Policy Kishimoto Osaka University) inaugurated Full-time member (Former Executive Representative Director & Managing Members Ayao Tsuge • 2001–2005 2nd Science Director, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd.) and Technology Basic Plan Reiko Kuroda Professor, the University of Tokyo President, Chief Executive Officer • 2006–2010 3rd Science Etsuhiko Shoyama and Director of Hitachi, -

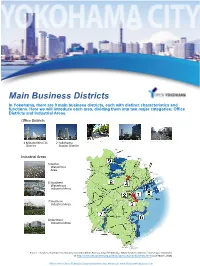

Main Business Districts in Yokohama, There Are 9 Main Business Districts, Each with Distinct Characteristics and Functions

Main Business Districts In Yokohama, there are 9 main business districts, each with distinct characteristics and functions. Here we will introduce each area, dividing them into two major categories: Office Districts and Industrial Areas. Office Districts 1 Minato Mirai 21 2 Yokohama 3 Kanna i Di stri ct 4 Shi n-Yok oh ama 9 K oh ok u Ne w District Station District Station District Town District Industrial Areas 5 Keihin Waterfront Area 6 Southern Waterfront Industrial Area 7 Southern Industrial Area 8 Northern Industrial Area Source : Business Development Division, Economic Affairs Bureau, City of Yokohama, “Main Business Districts,” Investing in Yokohama at http://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/keizai/yuchi/sinsyutu-e/districts.html (as of March, 2016) Office of the City of Yokohama Representative to the Americas | www.BusinessYokohama.com Office Districts 1. Minato Mirai 21 District • The new gateway of Yokohama, Japan's leading international city • Multiple functions, such as business, commerce, culture and entertainment are concentrated in this district • Construction of many new corporate headquarters and rental office buildings are expected Minato Mirai 21 (Future Port 21) is the name of a project launched with the intention to dramatically transform the metropolitan area of Yokohama. This project aims for the integration of the city's two major business districts (the Yokohama Station District and the Kannai District), the creation of new business and vitalization of the city. Its final goal is to create a district where 190,000 people work and 10,000 people live. This project has 3 visions: "A Round-the-Clock International Cultural City", "A 21st Century Information City", and "An Inviting City Offering an Ample Waterfront, Open Space and Heritage". -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents President’s Message .......................................................................................................................................5 JCIE Activities: April 2006–March 2008 .....................................................................................................8 Global ThinkNet Policy Research and Dialogue ................................................................................................................. 12 Asia Pacific Agenda Project The Development of Trilateral Cooperation among East Asia, North America, and Europe in Global Governance East Asia and a Rising India: Prospects for the Region 12th APAP Forum, Bali 13th APAP Forum, Singapore Dialogue and Research Monitor: Toward Community Building in East Asia ASEM’s Role in Enhancing Asia-Europe Cooperation: Ten Years of Achievements and Future Challenges East Asia Insights: Toward Community Building An Enhanced Agenda for US-Japan Partnership Human Security Approaches to HIV/AIDS in Asia and Africa Managing China-Japan-US Relations and Strengthening Trilateral Cooperation Survey of the State of US-China Policy-Oriented Intellectual Exchange and Dialogue Survey of US Congressional Approaches to East Asia After the Midterm Elections Preliminary Study on Community Perspectives on Human Security Survey of Trends in US-Japan Exchange Support and Cooperation for Research and Dialogue .......................................................................20 Trilateral Commission UK-Japan 21st Century Group Japanese-German Forum -

A Case Study of Hashima Island

University of Cape Town The ‘Social Life’ of industrial ruins: a case study of Hashima Island By Insoo Hong July 2015 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town The ‘social life’ of industrial ruins: a case study of Hashima Island Insoo Hong HNGINS002 A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in African Studies with a specialisation in Heritage and Public Culture Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2015 i DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in this dissertation from the work, or works, of other peoplepp has been attributed and has been cited and referenced. ii ABSTRATION The inscription of a strange-looking industrial site- coalmine on Hashima- on the World Heritage Site has proved to be the most publicly contested debate of heritage making work between Japan and Korea The debate about this place brings up poignant questions with regard to not only the significance of this heritage, but also the subsequent use of this island. The failure of reconciliation between countries especially, but also of reparation, restitution since the end of the Second World War and the issues of identity and memory have been brought to the fore. -

Access to Minato Mirai Hall

Access By train A 3-minute walk from Minatomirai Station (Minatomirai Line); go out of Queen's Square Yokohama Exit and take the escalator nearby. A 12-minute walk from Sakuragicho Station (JR Keihin-Tohoku Negishi Line, or Yokohama City Subway); over the moving walkway and through Landmark Plaza and Queen's Square shopping malls. By bus From Sakuragicho Station Bus Terminal Pole No.1: Boarding a bus No.57 and 145 to Queen's Square bus stop. From Yokohama Station East Exit Bus Terminal Pole No.14: Boarding a Keikyu bus to Queen's Square bus stop. By boat Boarding a "Sea Bass" boat at Yokohama Station East Exit and getting off at Pukari-Sambashi Pier. A 3-minute walk to the hall. Shuto Minatomirai Line ÒQueen's Expressway Yokohama to Yokohama to Yokohama Minatomirai SquareÓ Museum of Station Bus stop Art Rinko Park Minato Mirai 2 Artist Ramp 3 Entrance 1 Landmark QUEEN'S Queen's Yokohama Plaza EAST Tower C Minato Mirai Main Entrance 3rd Fl. [at!] 3rd Line Hall R Pacifico J Landmark to 2nd Fl. to 1st Fl. Queen Mall Yokohama Tower Pukari Sambashi Yokohama [at!] 2nd Pan Pacific oute 16 Queen's Pier R [at!] 1st Hotel Yokohama Tower A Yokohama Yokohama Grand Royal Park Hotel Intercontinental Hotel Queen's Square Ticket Center 2 To Loading Door(B1) Moving Nippon Maru Mall Entrance Walkway Memorial Park gicho to Motomachi-Chukagai Subway Station Sakura Parking Minato Mirai Public Parking (Pacifico Yokohama underground) 1200 vehicles/24hrs/260 yen per 30 min. to Kannai 1 2 Queen's Parking (Queen's Square underground) 1700 vehicles/7:00-24:00/260 yen per 30 min.