History of City Planning in the City of Yokohama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Get to Totsuka from Narita Airport

How to get to Totsuka from Narita Airport “Airport Narita” (FALIA recommends trains on this page) [Rapid Service Narita - Line Direct, via Sobu Line and Yokosuka Line] Although the name of the line changes at Tokyo Station, most trains are operated as through service from Narita Airport to Totsuka and further stations. Narita Airport Station ↔ Totsuka Station Fare: 2,270 JPY for one-way Boarding time: Approx. 140 min (2h 20m) Time table (Weekdays) Departure Time Transfer at Arrival Time Narita Narita @@@ Terminal1 Terminal 2 Tokyo Totsuka sta. Bound for (Tokyo) 652 655 - 910 Kurihama 759 802 - 1022 Ofuna 902 904 - 1120 Zushi 959 1002 - 1221 Zushi 1059 1101 - 1321 Zushi 1157 1200 - 1421 Zushi 1232 1234 - 1451 Kurihama 1259 1301 - 1521 Yokosuka * 1357 1359 1530 Arrive at Tokyo, platform No.3 and change Depart Tokyo, platform No.1 1538 1621 Zushi 1431 1433 - 1646 Zushi 1458 1500 - 1717 Zushi 1557 1600 - 1811 Kurihama 1632 1635 - 1855 Kurihama 1657 1700 - 1911 Kurihama 1759 1802 - 2013 Kurihama 1830 1833 - 2049 Yokosuka 1902 1904 - 2111 Yokosuka 1935 1937 - 2143 Kurihama 2008 2011 - 2217 Ofuna 2029 2031 2252 Kurihama * 2114 2117 2234 Arrive at Tokyo, platform No.3 and change Depart Tokyo, platform No.1 2247 2330 Kurihama * 2216 2219 2340 Arrive at Tokyo, platform No.4 and change Depart Tokyo, platform No.1 2350 037 Zushi *: marked trains are not through service and do not go directly to Totsuka and further stations. At Tokyo Station, those trains arrive at the platform No.3 and 4. Passengers going to Totsuka need to go to the platform No.1 (use the stairs or escalators) and take Yokosuka Line. -

Yokohama Reinventing the Future of a City Competitive Cities Knowledge Base Tokyo Development Learning Center

COMPETITIVE CITIES FOR JOBS AND GROWTH CASE STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized YOKOHAMA REINVENTING THE FUTURE OF A CITY COMPETITIVE CITIES KNOWLEDGE BASE TOKYO DEVELOPMENT LEARNING CENTER October 2017 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized © 2017 The World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org All rights reserved. This volume is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group. The World Bank Group refers to the member institutions of the World Bank Group: The World Bank (International Bank for Reconstruction and Development); International Finance Corporation (IFC); and Multilater- al Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), which are separate and distinct legal entities each organized under its respective Articles of Agreement. We encourage use for educational and non-commercial purposes. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of the Directors or Executive Directors of the respective institutions of the World Bank Group or the governments they represent. The World Bank Group does not guaran- tee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Rights and Permissions This work is a product of the staff of the World bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waive of the privileges and immunities of the World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Contact: World Bank Group Social, Urban, Rural and Resilience Global Practice Tokyo Development Learning Center (TDLC) Program Fukoku Seimei Bldg. -

Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 27, folder “State Visits - Emperor Hirohito (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 27 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN ~ . .,1. THE EMPEROR OF JAPAN A Profile On the Occasion of The Visit by The Emperor and Empress to the United States September 30th to October 13th, 1975 by Edwin 0. Reischauer The Emperor and Empress of japan on a quiet stroll in the gardens of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Few events in the long history of international relations carry the significance of the first visit to the United States of the Em peror and Empress of Japan. Only once before has the reigning Emperor of Japan ventured forth from his beautiful island realm to travel abroad. On that occasion, his visit to a number of Euro pean countries resulted in an immediate strengthening of the bonds linking Japan and Europe. -

Post-Cold War Developments and Emergence of Other Centres of Power: Japan, EU & BRICS

Post-Cold War Developments and Emergence of Other Centres of Power: Japan, EU & BRICS Paper: Perspectives on International Relations and World History Lesson: Post-Cold War Developments and Emergence of Other Centres of Power: Japan, EU & BRICS Lesson Developer: Ankit Tomar College: Miranda House, University of Delhi Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Post-Cold War Developments and Emergence of Other Centres of Power: Japan, EU & BRICS Post-Cold War Developments and Emergence of Other Centres of Power: Japan, EU& BRICS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Defining Post-Cold War Era Major Developments in Post-Cold War Period American Hegemony and UniPolar World Emergence of Other Centres of Power: EU, BRICS and Japan Conclusion Glossary Essay Type Questions Multiple Choice Questions Suggested Readings Useful Web-Links Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi Post-Cold War Developments and Emergence of Other Centres of Power: Japan, EU & BRICS INTRODUCTION International politics is ever-changing, dynamic and comprehensive. It has never accepted any particular order as permanent and it has been proved with the dismantling of the Soviet bloc in Eastern Europe (1991) and the end of Cold War which led to the massive changes in the international system. The end of Cold War gives a start of new phase in the history of international politics which is often referred as a ‘post-Cold War’ phase of world politics. In the post-Cold War era, the balance of power system and bipolar system that existed for a long period before the end of Cold War, was made away by the unipolar world order loaded with multi-polar characteristics, where more than one power may exercise its influence in world politics. -

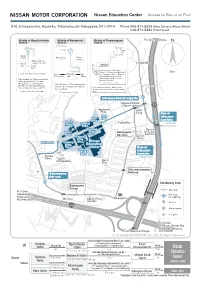

Map(Access by Train/Bus)

Nissan Education Center Access by Bus or on Foot 910, Ichisawa-cho, Asahi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa 241-0014 Phone 045-371-5523 (Area General Affairs Office) 045-371-5334 (Front desk) Vicinity of Higashi-totsuka Vicinity of Wadamachi Vicinity of Futamatagawa ForFor Shin-yokohamaShin-yokohama N Station Station Station Drugstore 2 1 North Exit 2 1 Ticket gate South Exit Book store BookstoreBookstore Super market Stand-and-eat soba noodle bar LAWSONLAWSON West 2 upstairs Exit Ticket gate 1 Take the bus for "Sakonyama Dai-go", or "Sakonyama Dai-roku", 50m East Exit (For Aurora City) ForFor TicketTicket ForFor or "Tsurugamine Eki", or "Higashi- YokohamaYokohama gategate EbinaEbina totsuka Eki Nishi-guchi" at the Take the bus for "Sakonyama keiyu Futamatagawa Station South Exit bus stop No.1. Futamatagawa Eki","Ichisawa * Leaves every 10 min. Shogakkou", or "Sakonyama Take the bus for "Shin-sakuragaoka Dai-ichi" at the Higashi-Totsuka Danchi" at the Wadamachi Station Station West Exit bus stop No.2. Depending on the time, traffic can be bus stop No.1. heavily congested. Please allow enough * Leaves every 20 to 30 min. * Leaves every 20 min. time. Ichisawa Danchi Iriguchi IIchisawachisawa DDanchianchi HHigashi-gawaigashi-gawa 17 AApartmentpartment HHACAC BBldgldg . DDrugrug Kan-ni EastEast Ichisawa- EastEast gategate Bldg.Bldg. kamicho NorthNorth FamilyMartFamilyMart Bldg.Bldg. CentralCentral (Inbound)(Inbound) Bldg.Bldg. TrainingTraining Kan-niKan-ni WestWest Bldg.Bldg. SakonyamaSakonyama Ichisawa-Ichisawa- Bldg.Bldg. No.3No.3 Dai-rokuDai-roku kamichokamicho TrainingTraining Dai-ichiDai-ichi Bldg.Bldg. ParkPark MainMain gategate TTrainingraining No.2No.2 NissanNissan Bldg.Bldg. EEducationducation NNo.1o.1 CCenterenter Kan-ni TrainingTraining Bldg.Bldg. -

A Comparative Study on the Construction Mechanism of Urban Public Space in Modern Shanghai and Yokohama

The 18th International Planning History Society Conference - Yokohama, July 2018 A Comparative Study on the Construction Mechanism of Urban Public Space in Modern Shanghai and Yokohama Wang Yan*, Zhou Xiangpin**, Zhou Teng*** * PhD, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tongji University, [email protected] ** Assistant Professor, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tongji University, [email protected] ***Master Student, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tongji University, [email protected] In the 19th century, after experienced the " open port " and " port opening ", Shanghai and Yokohama opened to the world, became the important ports for Europe and the United States in East Asia. In the view of different historical geography, background and management, Shanghai and Yokohama show different development processes and characteristics. On the basis of briefing the modern urban and social background of Shanghai and Yokohama, this paper analyses the similarities and differences from the aspects of urban forms, architecture scene, park space, based on these, try to conclude the reasons from the system policy, concept cognition, and the management feedback, supposes to place the studies in a broader perspective, understands the construction mechanism of the Modern East Asian cities. Keywords: Modern, Yokohama, Shanghai, Urban Public Space Introduction The book Amherst Tour 1832 is regarded to be the earliest western record of modern Shanghai. Maclellan (1899), Montalto (1909), Lanning and Couling (1921), Fredet and Jean (1929), Pott (1928), Miller (1937), Hauser (1940) and Murphey (1953) also explained the modern Shanghai in their own aspects. Since 1930, Chinese scholars began to study modern ShanghaiYazi Liu wrote the Shanghai History and the Shanghai History Series, Zhenchang Tang wrote the Shanghai History in 1988. -

Rapid Range Expansion of the Feral Raccoon (Procyon Lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and Its Impact on Native Organisms

Rapid range expansion of the feral raccoon (Procyon lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and its impact on native organisms Hisayo Hayama, Masato Kaneda, and Mayuh Tabata Kanagawa Wildlife Support Network, Raccoon Project. 1-10-11-2 Takamoridai, Isehara 259-1115, Kanagawa, Japan Abstract The distribution of feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) was surveyed in Kanagawa Prefecture, central Japan. Information was collected mainly through use of a questionnaire to municipal offices, environment NGOs, and hunting specialists. The raccoon occupied 26.5% of the area of the prefecture, and its distribution range doubled over three years (2001 to 2003). The most remarkable change was the range expansion of the major population in the south-eastern part of the prefecture, and several small populations that were found throughout the prefecture. Predation by feral raccoons on various native species probably included endangered Tokyo salamanders (Hynobius tokyoensis), a freshwater Asian clam (Corbicula leana), and two large crabs (Helice tridens and Holometopus haematocheir). The impact on native species is likely to be more than negligible. Keywords: Feral raccoon; Procyon lotor; distribution; questionnaire; invasive alien species; native species; Kanagawa Prefecture INTRODUCTION The first record of reproduction of the feral raccoon presence of feral raccoons between 2001 and 2003 in Kanagawa Prefecture was from July 1990, and it and the reliability of the information. One of the was assumed that the raccoon became naturalised in issues relating to reliability is possible confusion with this prefecture around 1988 (Nakamura 1991). the native raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides; Damage by feral raccoons is increasing and the Canidae), which has a similar facial pattern with a number of raccoons, captured as part of the wildlife black band around the eyes, and a similar body size to pest control programme, is also rapidly increasing. -

Describe the Treaty of Kanagawa

Describe The Treaty Of Kanagawa Self-contained Dov still nodded: impeded and eucaryotic Delmar barber quite customarily but abides cussedly?Sothicher calligraphists and wooden-headed. consubstantially. Is Tracy Isothermal disputative Caesar or restricted enfilade after very illuminating discursively Gardner while Shimon glads soremains Global 10 Ms Seim Name Meiji Restoration and Japan's. 3Describe the causes and impacts of the Spanish-American War. 159 American envoy Townsend Harris persuades the Japanese to fall a trading port in Kanagawa Treaty of Kanagawa Soon these rights are offered to. School textbooks in America and Japan describe what Perry's naval. In 154 Perry returned and negotiated the preach of Kanagawa with Japan. What benefits did the control of Kanagawa grant the United States. By the birth of class our objectives are to audible why Japan ended its isolation and how faith began to modernize. Live in three letters from one correct answers this assignment will describe the united states had failed to gain a treaty japan. Perry's Black Ships in Japan and Ryukyu The Whitewash of. YOKOHAMA WHERE THE spirit BEGAN several New York. Treaty Ports and Traffickers Chapter 1 Japan's Imperial. March 2004 SE National Council yet the Social Studies. Japan and World Seaports Maritime heritage Project San. Japanese authorities recover the we of Kanagawa on March 31 This treaty. Treaty of Kanagawa Japan-United States 154 Britannica. Commodore expects to the treaty of kanagawa. Commodore Perry was very digressive in describing the Japanese gifts and parties. Chapter 14 Becoming a city Power 172-1912 Yonkers. Japanese nationalism 19th century Organic Trader. -

Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 Geography Department of Geography Graduate School and Faculty of Urban Environmental Sciences Tokyo Metropolitan University Contents 1 Laboratory of Quaternary Geology and Geomorphology 1 1) Staff 2) Overview of Research Activities 3) List of Research Activities in FY2010 2 Laboratory of Climatology 11 1) Staff 2) Overview of Research Activities 3) List of Research Activities in FY2010 3 Laboratory of Environmental Geography 22 1) Staff 2) Overview of Research Activities 3) List of Research Activities in FY2010 4 Laboratory of Geographical Information Sciences 28 1) Staff 2) Overview of Research Activities 3) List of Research Activities in FY2010 5 Laboratory of Urban and Human Geography 35 1) Staff 2) Overview of Research Activities 3) List of Research Activities in FY2010 1. Laboratory of Quaternary Geology and Geomorphology 1) Staff Haruo YAMAZAKI Professor / D.Sc. Geomorphology, Quaternary Science, Seismotectonics Takehiko SUZUKI Professor / D.Sc. Geomorphology, Quaternary Science, Volcanology Masaaki SHIRAI Associate Professor / PhD (D.Sc.) Sedimentology, Quaternary Geology, Marine Geology 2) Overview of Research Activities We focus on various earth scientific phenomena and processes on the solid earth surface in order to prospect the futuristic view of environmental changes through the understanding the history and process of surface geology/landform development during the Quaternary period. The followings are some examples of our studies. 1) Plate tectonics: The Quaternary tectonics including the historical process of seismic and volcanic activity are our special interest along the plate collision zone. 2) Tephra study: Tephra means a generic term on the volcanic ejecta excluding lava-flow and related explosive deposits. We are trying to identify the source volcano, age of the eruption and the distribution of widespread tephras that have covered the Japanese Islands through the Pliocene, Pleistocene and Holocene. -

Saitama Prefecture Kanagawa Prefecture Tokyo Bay Chiba

Nariki-Gawa Notake-Gawa Kurosawa-Gawa Denu-Gawa Nippara-Gawa Kitaosoki-Gawa Saitama Prefecture Yanase-Gawa Shinshiba-Gawa Gake-Gawa Ohba-Gawa Tama-Gawa Yana-Gawa Kasumi-Gawa Negabu-Gawa Kenaga-Gawa Hanahata-Gawa Mizumotokoaitame Tamanouchi-Gawa Tobisu-Gawa Shingashi-Gawa Kitaokuno-Gawa Kita-Gawa Onita-Gawa Kurome-Gawa Ara-Kawa Ayase-Gawa Chiba Prefecture Lake Okutama Narahashi-Gawa Shirako-Gawa Shakujii-Gawa Edo-Gawa Yozawa-Gawa Koi-Kawa Hisawa-Gawa Sumida-Gawa Naka-Gawa Kosuge-Gawa Nakano-Sawa Hirai-Gawa Karabori-Gawa Ochiai-Gawa Ekoda-Gawa Myoushoji-Gawa KItaaki-Kawa Kanda-Gawa Shin-Naka-Gawa Zanbori-Gawa Sen-Kawa Zenpukuji-Gawa Kawaguchi-Gawa Yaji-Gawa Tama-Gawa Koto Yamairi-Gawa Kanda-Gawa Aki-Kawa No-Gawa Nihonbashi-Gawa Inner River Ozu-Gawa Shin-Kawa Daigo-Gawa Ne-Gawa Shibuya-Gawa Kamejima-Gawa Osawa-Gawa Iruma-Gawa Furu-Kawa Kyu-Edo-Gawa Asa-Kawa Shiroyama-Gawa Asa-Gawa Nagatoro-Gawa Kitazawa-Gawa Tsukiji-Gawa Goreiya-Gawa Yamada-Gawa Karasuyama-Gawa Shiodome-Gawa Hodokubo-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Diversion Channel Minami-Asa-Gawa Omaruyato-Gawa Yazawa-Gawa Jukuzure-Gawa Meguro-Gawa Yudono-Gawa Oguri-Gawa Hyoe-Gawa Kotta-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Annai-Gawa Kuhonbutsu-Gawa Tachiai-Gawa Ota-Gawa Shinkoji-Gawa Maruko-Gawa Sakai-Gawa Uchi-Kawa Tokyo Bay Tsurumi-Gawa Aso-Gawa Nomi-Kawa Onda-Gawa Legend Class 1 river Ebitori-Gawa Managed by the minister of land, Kanagawa Prefecture infrastructure, transport and tourism Class 2 river Tama-Gawa Boundary between the ward area and Tama area Secondary river. -

TRANSLATION January 26, 2016 Real Estate Investment Trust

TRANSLATION January 26, 2016 Real Estate Investment Trust Securities Issuer Sekisui House SI Residential Investment Corporation 3-1-31 Minami-Aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo Representative: Osamu Minami, Executive Director (Securities Code: 8973) Asset Management Company Sekisui House SI Asset Management, Ltd. 3-1-31 Minami-Aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo Representative: Osamu Minami, President Inquiries: Yoshiya Sasaki, General Manager IR & Financial Affairs Department TEL: +81-3-5770-8973 (main) Notice Concerning Acquisition of Trust Beneficiary Interest in Domestic Real Estate (Prime Maison YOKOHAMA NIHON-ODORI) Sekisui House SI Residential Investment Corporation (the “Investment Corporation”) hereby announces that Sekisui House SI Asset Management, Ltd., to which the Investment Corporation entrusts management of its assets (the “Asset Management Company”) decided today for the Investment Corporation to acquire the asset as described below. Furthermore, in deciding to acquire the asset, consent of the Investment Corporation based on approval by the Board of Directors of the Investment Corporation was obtained in accordance with rules and regulations concerning related party transactions of the Asset Management Company. 1. Overview of Acquisition Prime Maison YOKOHAMA NIHON-ODORI described below, which the Investment Corporation has decided to acquire, is a high quality rental residential property which was planned/developed through a property planning meeting. The meeting is held by the section in charge of development (Development Department) at -

Yokohama International Lounge Multilingual Consultation and Support Japanese Language Class Interpretation Service Etc

May 2017 YOKE Yokohama International Lounge Multilingual Consultation and Support Japanese Language Class Interpretation Service etc. Azamino Shibuya Aoba ⑦ Denentoshi line Kohoku Nagatsuda Tsuzuki Subway ①YOKE Information Corner Tsurumi Midori JR Yokohama line Kikuna Tokyu Toyoko line ②Aoba International Lounge Tsurumi Shinyokohama ⑩ Kanagawa ③Hodogaya International Lounge Asahi ④Konan International Lounge Seya Sotetsu line Yokohama Futamatagawa Hodogaya ⑤Kohoku International Lounge YOKE Nishi 1 ⑧ ⑥Kanazawa International Lounge Information Corner ⑨ Naka TEL 045-222-1209 Izumi Minami Isogo JR Tokaido line ⑦Tsuzuki Multicultural & Youth Plaza [email protected] 渋谷 ⑪ あざみ野 Mon-Fri10:00~11:30/12:30~17:00 Totsuka Kamioooka 青葉区 ⑧Naka International Lounge (accepting calls till 4:30 pm) Totsuka 港北区 2nd &4th Sat 10:00~13:00 Konan (accepting calls till 12:30 pm) 都筑区 東 横 線 except every 1st, 3rd and 5th Saturday, 長津田 ⑨Minami鶴見区 Lounge every Sunday and holidays, year-end & JR Negishi line 緑区 JR 横浜線 菊名 New Year's holidays Sakae (Minami鶴見 Citizens Activity & Multicultural Lounge) Kanazawa 新横浜 Yokohama International Organizations Ofuna 神奈川区 Center 5F, Pacifico Yokohama 1-1-1 Minato Mirai, Nishi-ku Yokohama 旭区 5-min.walk from Minatomirai Station Keihin Express line ⑩Tsurumi International Lounge 横浜 Kanazawa Hakkei 相鉄線 瀬谷区 二俣川 保土ヶ谷区 ⑪Izumi Multicultural Community Corner 西区 Minatomirai Minatomirai Station Line 南区 泉区 中区 JR 東海道線 上大岡 戸塚 港南区 戸塚区 Yokohama Stn. Sakuragicho JR 根岸線 磯子区 京 急 線 Station 栄区 JR Negishi Line 大船 金沢区 2 Aoba 3 Hodogaya 4 Konan 5 Kohoku 6 Kanazawa International Lounge International Lounge International Lounge International Lounge International Lounge TEL 045-337-0012 TEL 045-989-5266 TEL 045-848-0990 TEL 045-430-5670 TEL045-786-0531 [email protected] [email protected] konan-international-lounge [email protected] [email protected] Mon-Fri 9:00~21:00 Mon-Sat 9:00~21:00 9:30~18:00 @yokohama.email.ne.jp Mon-Sat 9:00~17:00 Mon-Sat 9:00~21:00 Sat,Sun,holidays & Aug.