Yokohama Reinventing the Future of a City Competitive Cities Knowledge Base Tokyo Development Learning Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

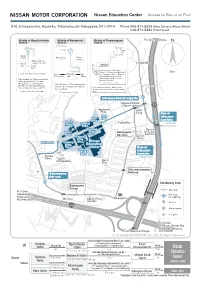

Map(Access by Train/Bus)

Nissan Education Center Access by Bus or on Foot 910, Ichisawa-cho, Asahi-ku, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa 241-0014 Phone 045-371-5523 (Area General Affairs Office) 045-371-5334 (Front desk) Vicinity of Higashi-totsuka Vicinity of Wadamachi Vicinity of Futamatagawa ForFor Shin-yokohamaShin-yokohama N Station Station Station Drugstore 2 1 North Exit 2 1 Ticket gate South Exit Book store BookstoreBookstore Super market Stand-and-eat soba noodle bar LAWSONLAWSON West 2 upstairs Exit Ticket gate 1 Take the bus for "Sakonyama Dai-go", or "Sakonyama Dai-roku", 50m East Exit (For Aurora City) ForFor TicketTicket ForFor or "Tsurugamine Eki", or "Higashi- YokohamaYokohama gategate EbinaEbina totsuka Eki Nishi-guchi" at the Take the bus for "Sakonyama keiyu Futamatagawa Station South Exit bus stop No.1. Futamatagawa Eki","Ichisawa * Leaves every 10 min. Shogakkou", or "Sakonyama Take the bus for "Shin-sakuragaoka Dai-ichi" at the Higashi-Totsuka Danchi" at the Wadamachi Station Station West Exit bus stop No.2. Depending on the time, traffic can be bus stop No.1. heavily congested. Please allow enough * Leaves every 20 to 30 min. * Leaves every 20 min. time. Ichisawa Danchi Iriguchi IIchisawachisawa DDanchianchi HHigashi-gawaigashi-gawa 17 AApartmentpartment HHACAC BBldgldg . DDrugrug Kan-ni EastEast Ichisawa- EastEast gategate Bldg.Bldg. kamicho NorthNorth FamilyMartFamilyMart Bldg.Bldg. CentralCentral (Inbound)(Inbound) Bldg.Bldg. TrainingTraining Kan-niKan-ni WestWest Bldg.Bldg. SakonyamaSakonyama Ichisawa-Ichisawa- Bldg.Bldg. No.3No.3 Dai-rokuDai-roku kamichokamicho TrainingTraining Dai-ichiDai-ichi Bldg.Bldg. ParkPark MainMain gategate TTrainingraining No.2No.2 NissanNissan Bldg.Bldg. EEducationducation NNo.1o.1 CCenterenter Kan-ni TrainingTraining Bldg.Bldg. -

Print (1.08MB)

December 3, 2018 For immediate release Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd. Mitsui Fudosan’s Outlet Park Reconstruction Business MITSUI OUTLET PARK YOKOHAMA BAYSIDE Reconstruction Plan (tentative name) Started Construction on December 3 Opening Planned for Spring 2020 Tokyo, Japan, December 3, 2018 - Mitsui Fudosan Co., Ltd., a leading global real estate company headquartered in Tokyo, announced today that it has started new construction work on the MITSUI OUTLET PARK YOKOHAMA BAYSIDE Reconstruction Plan (tentative name), located at 5-2 Shiraho, Kanazawa-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa. The facility is planned to reopen in spring 2020. This plan is located on a site with outstanding access by car or public transport, being approx. 1.5 km from Sugita IC on the Metropolitan Expressway Bayshore Route, approx. 1.5 km from the Namiki IC on Yokohama-Yokosuka Road and 5 minutes on foot from Torihama Station on the Yokohama Seaside Line. Since commencing operation in September 1998, MITSUI OUTLET PARK YOKOHAMA BAYSIDE ("Yokohama Bayside Marina Shops & Restaurants" at the time of opening), has been cherished by many visitors. The facility is temporarily closed for renovations to create facilities and functions that meet the needs of customers and the times. Exterior Image (southeast side) 1 / 5 Main Features of the Facility 1. Retail Functions Under this plan, the previous approx. 80 stores is planned to be expanded to approx. 150 stores. MITSUI OUTLET PARK YOKOHAMA BAYSIDE will strive to be a facility where a broad range of visitors of all ages—from youths and families to seniors—can enjoy a richer lineup of brands such as fashion brands from inside and outside of Japan, select refined shops, children’s goods, sports & outdoor goods, and daily use miscellany. -

10. Sources and Useful Links

10. Sources and useful links Keio and SFC ・Keio University Jyukusei website : http://www.gakuji.keio.ac.jp/index.html ・SFC- Housing Information for International Students: http://www.gakuji.keio.ac.jp/en/sfc/sl/housing.html ・Keio University International Center – Housing for International Students: http://www.ic.keio.ac.jp/en/life/housing/ryu_boshu.html Housing Information ・Housemate – Shonandai branch: http://www.housemate-navi.jp/shop/59 ・Mini Mini - Shonandai branch: http://minimini.jp/shop/10016/shonandai/index.html ・Leopalace 21: For International Students: http://en.leopalace21.com/students/ ・ABLE: For International Students: http://www.able.co.jp/international/ ・Kyoritsu Maintenance: http://www.gakuseikaikan.com/international/english/index.html http://www.kif-org.com/placehall/e04.html ・Tokyo Sharehouse: http://tokyosharehouse.com/eng ・Oakhouse: http://www.oakhouse.jp/eng/ ・Sakura House: http://www.sakura-house.com/en ・Sharetomo Program http://www.sharetomo.jp/ Visa and Administration ・Immigration Bureau of Japan: http://www.immi-moj.go.jp/newimmiact_1/en/index.html ・Fujisawa City: https://www.city.fujisawa.kanagawa.jp/jinkendanjyo/gaikokugo/english/index.html ・Yamato City: http://www.city.yamato.lg.jp.e.gg.hp.transer.com/ http://www.city.yamato.lg.jp/web/content/000143006.pdf ・Chigasaki City: http://www.city.chigasaki.kanagawa.jp.e.ox.hp.transer.com/about/1010015.html http://www.city.chigasaki.kanagawa.jp.e.ox.hp.transer.com/kankyo/ 89 ・Yokohama City: http://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/lang/en/ http://www.city.yokohama.lg.jp/lang/en/5-3-1.html -

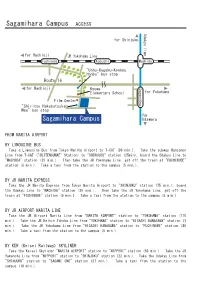

Sagamihara Campus ACCESS Odakyu Line

Sagamihara Campus ACCESS Odakyu line for Shinjuku for Hachioji JR Yokohama Line Fuchinobe Kobuchi Machida "Uchu-Kagaku-Kenkyu Honbu" bus stop Route 16 for Hachioji Kyowa SagamiOno Elementary School for Yokohama Film Center "Shiritsu Hakubutsukan Mae" bus stop for Sagamihara Campus Odawara FROM NARITA AIRPORT BY LIMOUSINE BUS Take a Limousine Bus from Tokyo Narita Airport to T-CAT (90 min.). Take the subway Hanzomon Line from T-CAT ("SUITENGUMAE" Station) to "SHINJUKU" station (25min), board the Odakyu Line to "MACHIDA" station (35 min.). Then take the JR Yokohama Line, get off the train at "FUCHINOBE" station (6 min.). Take a taxi from the station to the campus (5 min.). BY JR NARITA EXPRESS Take the JR Narita Express from Tokyo Narita Airport to "SHINJUKU" station (75 min.), board the Odakyu Line to "MACHIDA" station (35 min.). Then take the JR Yokohama Line, get off the train at "FUCHINOBE" station (6 min.). Take a taxi from the station to the campus (5 min.). BY JR AIRPORT NARITA LINE Take the JR Airport Narita Line from "NARITA AIRPORT" station to "YOKOHAMA" station (110 min.). Take the JR Keihin Tohoku Line from "YOKOHAMA" station to "HIGASHI KANAGAWA" station (3 min.). Take the JR Yokohama Line from "HIGASHI KANAGAWA" station to "FUCHINOBE" station (40 min.). Take a taxi from the station to the campus (5 min.). BY KER (Keisei Railway) SKYLINER Take the Keisei Skyliner "NARITA AIRPORT" station to "NIPPORI" station (50 min.). Take the JR Yamanote Line from "NIPPORI" station to "SHINJUKU" station (22 min.). Take the Odakyu Line from "SHINJUKU" station to "SAGAMI ONO" station (37 min.). -

YOKOHAMA TRAVEL Info SPOT LIST (As of Dec 20

YOKOHAMA TRAVEL info SPOT LIST (as of Dec 20. 2018) Welcome to Yokohama! May I help you? Yokohama Travel Info Spot offers services such as sightseein maps of Yokohama, pamphlets, and information about nearby attractions. Look for the logo right side and stop by anytime. You can also check the list below for the location nearest you. Have a nice trip!! Locations Service Available Provide Tourist Internet- Money Free No multi- sightseeing Free Public Rest Copy Nursing Facilities Maps connected Exchange Telephone Toilets Rental of Others Area lingualization information of Wi-Fi Space Service Room Available Computer ・ATM Umbrella Yokohama Sightseeing Facilities Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) 1 1 Yokohama International Center English Multilingual ● ● Minato Mirai 21 2-3-1, Shinko, Naka-ku, Yokohama Area ℡ 045-663-3251 *closed on Mondays Yokohama Cosmoworld 2 2 2-8-1, Shinko, Naka-ku, Yokohama Japanese ● ● ● ● ℡045-641-6591 *closed on Thursdays Nogeyama Zoological Gardens 63-10, Oimatsu-cho,Nishi-ku Yokohama Sakuragicho/ chargeable 3 3 ℡045-231-1307 English Japanese ● ● ● ● Noge Area call *closed on Mondays (open if holiday, except May & Oct.) Zou-no-Hana Terrace 4 4 1, Kaigan-dori, Naka-ku, Yokohama English Multilingual ● ● ● ● ℡045-661-0602 Osanbashi Yokohama International pay 5 5 Passenger Terminal English Japanese ● ● ● ● ● ● 97-4, Yamashita-cho, Naka-ku, Yokohama service Yamashita ℡045-681-5588 Park/Chinatown Area Yokohama Daisekai 6 6 1-1-4, Kaigan-dori, Naka-ku, Yokohama English, Chinese Japanese ● ● ℡045-211-2304 Yokohama -

Why Kanagawa? Business Environment & Investment Incentives

Why Kanagawa? Business Environment & Investment Incentives Investment Environment International Business Group Investment Promotion and International Business Division Industry Department Industry and Labor Bureau Kanagawa Prefectural Government Leading the way in adopting Western culture, Japan’s modernization began here. 1 Nihon-Odori, Naka-ku, Yokohama, Kanagawa Located the ideal distance from Tokyo, Kanagawa retains its own unique appeal. 231-8588 Japan Rich natural environments from the shores of Shonan to the mountains of Hakone. Rail and highway networks encompassing the Tokyo Metro Area. Tel: +81-45-210-5565 http://www.pref.kanagawa.jp/div/0612/ And now, with the new investment incentive program, “Select Kanagawa 100,” KANAGAWA will shine even brighter! June 2016 Welcome to Kanagawa Prefecture Forming a mega-market with the bordering capital city of Tokyo, Kanagawa Prefecture itself boasts a population exceeding 9.1 million. It is home to a high concentration of R&D facilities and offices of multinational corporations, as well as many small- and medium-sized businesses with exceptional technological capabilities. In addition to an expansive and well-developed highway and rail network, Kanagawa also offers extensive urban facilities and industrial infrastructure, including the international trading ports of Yokohama, Kawasaki, and Yokosuka, with Haneda International Airport located nearby. Kanagawa is also blessed with a lush natural environment of verdant mountains and picturesque coastlines, and features numerous sightseeing spots which encapsulate all of Japan’s charms. These include the international port city of Yokohama, the historic and culturally vibrant ancient samurai capital of Kamakura, and Hakone, the international tourist destination known for its hot springs and magnificent scenery of Mt. -

Shaping Smart Cities -Experience of UR, Japan

Shaping Smart Cities -Experience of UR, Japan- NAKAYAMA Yasufumi Director General of Business Strategy Office Urban Renaissance Agency (UR) History of Urban Renaissance Agency (UR) Transition of the Organization 1955 1981 1999 2004 JHC HUDC UDC Japan Housing Corporation Housing and Urban Urban Development 1975 Urban Land Development Corporation Development Corporation Renaissance Corporation Agency 1974 • Staff: 3,152 Japan Regional Development Corporation • Capital: 10 billion USD Businesses in line with Policy Purposes (as of March, 2019) Mass supply of Houses and Residential Land Improvement of Living Environment Urban and City Functions Revitalization Economic and Social Situation of Japan Rapid Economic Growth Steady Economic Growth Maturation Period Economy: from 1950s to 1970s from 1970s to 1990s from 2000 Declining Birthrate Population: Population Bonus Population Peak and Aging Population Tokyo Baby Boom Privatization of in 2010 Great Hanshin-Awaji Great East Japan Events: Olympic in 1970s Japan National Earthquake in 1995 Earthquake in 2011 In 1964 Railway in 1987 Copyright© Urban Renaissance Agency All rights reserved. 1 Business fields of UR in Japan Urban Renewal In cooperation with private businesses and local authorities. To coordinate Vision, Planning and Conditions To join the project as a partner Minato Mirai 21 (Yokohama) New Town Development Safe and comfortable life in the suburbs To advance safe, secure, and eco-friendly city building coping with aging population and lower birthrate To realize attractive suburban life or local living Tama New Town(Tokyo) Rental Housing Manages and provides rich living space. To manage rental housing through cherishing trust relationship with 720,000 units To promote to live in the urban center, to secure stable rental housing for elderly, to improve child care environment. -

Tozaisen Ichikawa Myoden-Ekimae

TOZAISEN ICHIKAWA MYODEN-EKIMAE SUPER HOTEL TOZAISEN ICHIKAWA MYODEN-EKIMAE URL : http://www.superhotel.co.jp mobile : http://www.sh-mb.com/ Free healthy breakfast August 2014 renewal opening! Within Tokyo, perfect for access to Disney Resort, Makuhari Messe, and other local attractions. Recommended for both business and tourism! Guest Rooms Single room (up to 2 guests) 12m2 Super room (up to 3 guests) 12m2 Triple room (up to 4 guests) 18m2 (May not appear exactly as shown) (May not appear exactly as shown) (May not appear exactly as shown) Wide bed (150 cm wide) Wide bed (150 cm wide) + loft bed Wide bed (150 cm wide) + loft bed + sofa bed Healthy Breakfast Free Standard Amenities and Facilities in Every Guest Room [Room Facilities] [Amenities] ● 26-inch widescreen LCD TV ● Movies on demand (VOD, 150 titles) ● Toothbrush ● Bath towel ● Complimentary high-speed Internet (LAN) ● Face towel ● Refrigerator ● Air purifier with humidifier ● Two-in-one shampoo ● Unit bathroom ● Bidet ● Hair dryer ● Body soap (May not appear exactly as shown) ● Electric kettle ● Mobile charger ● Pajamas (available on the 6th floor) Super Hotel salads are safe and healthy. [Loanable Items, Other Items] [Hotel Facilities] Made with only organic ● Choice of 7 types of pillows ● Blankets ● Thermometer ● Coin-operated laundry *Free detergent JAS vegetables. ● Light stand ● Trouser press ● Iron ● Sewing set (Clothes washer: 100 yen per use, ● Can opener ● Wine-bottle opener ● Nail clippers Clothes dryer: 100 yen per 30 minutes) We provide a nutritionally balanced and healthy ● Mobile charger ● Copy service (fees apply) ● Vending machines (soft drinks, alcoholic beverages) breakfast for all guests. -

Teamlab Future Park

Kanagawa sightseeing charm cration conference Shonan <Mag-cul・Amusement> Hiratsuka City Think with your body, Tourist Attraction No. and grow through collaborative creation. 1901 teamLab Future Park Get creative by moving around and drawing in this digital art space. Color your favorite sea creatures or buildings with crayons and see it come to life in Explanation of the aquarium or in the town. The space has nine artworks including "Sliding Tourist Attraction through the Fruit Field", "Sketch Town", and "Sketch Aquarium." teamLab has created a space for family fun in ""Lalaport Shonan Hiratsuka"" selling point alongside the commercial center's restaurants and shopping areas. This permanent teamLab space is one of only four in all of Japan. Address LaLaport SHONAN HIRATSUKA 3F 700-17 Amanuma Hiratsuka-shi Kanagawa-ken Opening Hours 10:00-18:00 (Last admission 17:30) Corresponds with the days of operation of Lalaport Shounan Hiratsuka. Availability of Parking Use Lalaport Shonan-Hiratsuka Car Park (3,000 spaces) URL https://futurepark.teamlab.art/event/lalaporthiratsuka Recommended Season All year Access Group/Individual Mark Individual ①From bus stop 5 of the north exit of Hiratsuka Station on JR Tokaido Line take a Kanagawa Target Regions Europe, North America, Oceania, Asia Chuo Bus bound for Hiratukaeki-Kitaguchi (Hira 11 Route) for about 5 minutes. Get off at the Lalaport Shonan-Hiratsuka bus stop. ②12 mins. walk from Hiratsuka Station (JR Tokaido Line) Specific Model Route Details Individual JR Tokaido Line [Yokohama Station] +++(30 -

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN

YOKOHAMA and KOBE, JAPAN Arrive Yokohama: 0800 Sunday, January 27 Onboard Yokohama: 2100 Monday, January 28 Arrive Kobe: 0800 Wednesday, January 30 Onboard Kobe: 1800 Thursday, January 31 Brief Overview: The "Land of the Rising Sun" is a country where the past meets the future. Japanese culture stretches back millennia, yet has created some of the latest modern technology and trends. Japan is a study in contrasts and contradictions; in the middle of a modern skyscraper you might discover a sliding wooden door which leads to a traditional chamber with tatami mats, calligraphy, and tea ceremony. These juxtapositions mean you may often be surprised and rarely bored by your travels in Japan. Voyagers will have the opportunity to experience Japanese hospitality first-hand by participating in a formal tea ceremony, visiting with a family in their home in Yokohama or staying overnight at a traditional ryokan. Japan has one of the world's best transport systems, which makes getting around convenient, especially by train. It should be noted, however, that travel in Japan is much more expensive when compared to other Asian countries. Japan is famous for its gardens, known for its unique aesthetics both in landscape gardens and Zen rock/sand gardens. Rock and sand gardens can typically be found in temples, specifically those of Zen Buddhism. Buddhist and Shinto sites are among the most common religious sites, sure to leave one in awe. From Yokohama: Nature lovers will bask in the splendor of Japan’s iconic Mount Fuji and the Silver Frost Festival. Kamakura and Tokyo are also nearby and offer opportunities to explore Zen temples and be led in meditation by Zen monks. -

Environmental & Social Report 2013

2013 Environmental & Social Report Introduction Feature Article HSE The Environment Society ▲ 2 Editorial Policy Initiatives at the JGC Group Aimed at Becoming the Leading Global Health, The JGC Group’s Environmental Activities as a Corporate Citizen ▲ Realizing a Sustainable Society Safety, and the Environment Contractor Technologies and Environmental 3 Message from the Chairman 41 Sustainable Development for Both ▲ Conservation Activities ▲ 15 Efforts to Promote Renewable Energy 20 JGC Aims for Zero Energy-Consuming Countries and ▲ 5 JGC Group’s CSR Policy ▲ Incidents and Injuries 30 Development of NOx Removal Catalysts Resource-Producing Countries ▲ ▲ 17 Our Efforts to Develop Relationships with Major Stakeholders ▲ for Overseas Markets 7 Smart Communities 22 Health, Safety, and Environmental 43 Personnel Development and ▲ ▲ Considerations Associated with Communication with Employees 8 Corporate Governance ▲ 31 The JGC Group’s ▲ Business Activities ▲ ▲ Environmental Management 44 Our Contributions to Society 10 Risk Management ▲ 26 Occupational Health and Safety ▲ 32 Continuous Improvement of ▲ 11 Operations of the JGC Group Management Systems 28 Safety and Environmental ▲ 13 The JGC Group’s Environmental Measures Consideration in Investment Projects and Environmental Objectives, Targets, ▲ 33 ▲ Research & Development and Achievement ▲ 35 Environmental Report on Office Activities ▲ 37 Using JGC’s Environmental Technology to Solve Difficult Issues About JGC The JGC Group Name: Employees (approx.): As an engineering contractor, the JGC Total Engineering Business (EPC Business) Group’s core business is providing planning, JGC JGC Corporation 12,000 persons (as of March 2013) design engineering, equipment procurement, JGC Plant Innovation Co., Ltd.* JGC: 2,200 persons JGC Philippines Domestic EPC Affiliates: 3,200persons construction (EPC), and commissioning JGC Gulf International and others Overseas EPC Affiliates: 4,600persons services for various industrial plants and Catalyst, Fine Chemicals and Other Businesses 2,000 persons facilities. -

History of City Planning in the City of Yokohama

History of City Planning in the City of Yokohama City Planning Division, Planning Department, Housing & Architecture Bureau, City of Yokohama 1. Overview of the City of Yokohama (1) Location/geographical features Yokohama is located in eastern Kanagawa Prefecture at 139° 27’ 53” to 139° 43’ 31” East longitude and 35° 18’ 45” to 35° 35’ 34” North latitude. It faces Tokyo Bay to the east and the cities of Yamato, Fujisawa, and Machida (Tokyo) to the west. The city of Kawasaki lies to the north, and the cities of Kamakura, Zushi, and Yokosuka are to the south. Yokohama encompasses the largest area of all municipalities in the prefecture and is the prefectural capital. There are also rolling hills running north-south in the city’s center. In the north is the southernmost end of Tama Hills, and in the south is the northernmost end of Miura Hills that extends to the Miura Peninsula. A flat tableland stretches east-west in the hills, while narrow terraces are partially formed along the rivers running through the tableland and hills. Furthermore, valley plains are found in the river areas and coastal lowland on the coastal areas. Reclaimed land has been constructed along the coast so that the shoreline is almost entirely modified into manmade topography. (2) Municipal area/population trends The municipality was formed in 1889 and established the City of Yokohama. Thereafter, the municipal area was expanded, a ward system enforced, and new wards created, resulting in the current 18 wards (administrative divisions) and an area of 435.43km2. Although the population considerably declined after WWII, it increased by nearly 100,000 each year during the period of high economic growth.