Leonardo Da Vinci Society Newsletter Editor: Francis Ames-Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papers of the British School at Rome Some Drawings from the Antique

Papers of the British School at Rome http://journals.cambridge.org/ROM Additional services for Papers of the British School at Rome: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Some Drawings from the Antique attributed to Pisanello G. F. Hill Papers of the British School at Rome / Volume 3 / January 1906, pp 296 - 303 DOI: 10.1017/S0068246200005043, Published online: 09 August 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068246200005043 How to cite this article: G. F. Hill (1906). Some Drawings from the Antique attributed to Pisanello. Papers of the British School at Rome, 3, pp 296-303 doi:10.1017/S0068246200005043 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ROM, IP address: 128.233.210.97 on 12 Mar 2015 PAPERS OF THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT ROME VOL. III. No. 4 SOME DRAWINGS FROM THE ANTIQUE ATTRIBUTED TO PISANELLO BY G. F. HILL, M.A. LONDON: 1905 SOME DRAWINGS FROM THE ANTIQUE ATTRIBUTED TO PISANELLO. A CERTAIN number of the drawings ascribed to Pisanello, both in the Recueil Vallardi in the Louvre and elsewhere, are copies, more or less free, of antique originals.1 The doubts which have been expressed, by Courajod among others, as to the authenticity of some of these drawings are fully justified in the case of those which reproduce ancient coins. Thus we have, on fol. 12. no. 2266 v° of the Recueil Vallardi, a coin with the head of Augustus wearing a radiate crown, inscribed DIVVS AVGVSTVS PATER, and a head of young Heracles in a lion's skin, doubtless taken from a tetradrachm of Alexander the Great. -

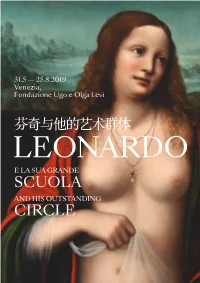

Scuola Circle 芬奇与他的艺术群体

31.5 — 25.8.2019 Venezia, Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi 芬奇与他的艺术群体 E LA SUA GRANDE SCUOLA AND HIS OUTSTANDING CIRCLE 31.5 — 25.8.2019 Venezia, Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi 芬奇与他的艺术群体 E LA SUA GRANDE SCUOLA AND HIS OUTSTANDING CIRCLE A cura di | Curator | 展览策展人 Nicola Barbatelli 尼古拉·巴尔巴泰利 Nota introduttiva di | Introduced by | 序言 Giovanna Nepi Scirè 乔凡娜·内皮·希雷 LEONARDO LEONARDO E LA SUA GRANDE SCUOLA AND HIS OUTSTANDING CIRCLE Palazzo Giustinian Lolin ospita fino al 25 agosto 2019 un importante tributo al genio Palazzo Giustinian Lolin hosts until 25 August 2019 an important tribute to the genius of di Leonardo Da Vinci, in occasione delle celebrazioni del cinquecentenario dalla Leonardo Da Vinci, on the occasion of the celebrations marking the 500th anniversary of scomparsa: la mostra “Leonardo e la sua grande scuola”, a cura di Nicola Barbatelli. Leonardo da Vinci’s death: the exhibition “Leonardo and His Outstanding Circle”, curated by Con 25 opere esposte – di cui due disegni attribuiti al genio toscano – il progetto pone Nicola Barbatelli. Proposing a collection of 25 works — among which two drawings attributed l’accento non solo sull’opera del grande Maestro, ma soprattutto sulle straordinarie to the Tuscan genius —, this project does not merely focus on the work of the great master, pitture dei suoi seguaci – tra cui Giampietrino, Marco d’Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto, but above all on the extraordinary paintings of his followers — including Giampietrino, Marco Salaì, Bernardino Luini – e il loro dialogo con la poetica artistica di Leonardo. d’Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto, Salaì, Bernardino Luini — and their dialogue with Leonardo’s artistic poetics. -

2016 Direttori Editoriali Agostino Allegri, Giovanni Renzi

IX 2016 Direttori editoriali Agostino Allegri, Giovanni Renzi Direttore responsabile Maria Villano Redazione Patrizio Aiello, Agostino Allegri, Chiara Battezzati, Serena Benelli, Giulio Dalvit, Elisa Maggio, Giovanni Renzi, Massimo Romeri Comitato scientifico Elisabetta Bianchi, Marco Mascolo, Antonio Mazzotta, Federica Nurchis, Paolo Plebani, Paolo Vanoli e-mail: [email protected] web: http://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/concorso Crediti fotografici: Worcester Art Museum: p. 28, fig. 2; Museo Diocesano, Genova: p. 29, fig. 3; Studio Perotti, Milano: p. 38, fig. 1; Confraternita del Santissimo Sacramento, Mogliano: p. 41, fig. 2; Francesco Benelli, Bologna: p. 43, fig. 3; Veronica Cassini: p. 48, fig. 1. La redazione si dichiara a disposizione degli aventi diritto per eventuali omissioni o imprecisioni nelle citazioni delle fonti fotografiche. © 2016 Lubrina Editore Srl via Cesare Correnti, 50 - 24124 Bergamo - cell. 3470139396 e-mail: [email protected] - web: www.lubrina.it ISSN: 2421-5376 ISBN: 978-88-7766-609-3 Aut. del Tribunale di Milano n° 223 del 10 luglio 2015 Questa rivista è realizzata con il finanziamento dell’Università degli Studi di Milano ai sensi della legge 3 agosto 1985, n° 429. Sommario Editoriale 5 Chiara Battezzati, Per Leonardo da Besozzo a Napoli, circa 1835 7 Claudio Gulli, La «Madonna Greca» di Pier Francesco Sacchi ad Alcamo: contesto lombardo e via ligure 29 Stefano Martinella, Appunti per l’attività marchigiana di «Petrus Francescus Renulfus Novariensis» 41 Veronica Cassini, Giuseppe Vismara a -

Altichiero in the Fifteenth Century, RIHA Journal 0073

RIHA Journal 0073 | 12 August 2013 Oblivion Deferred: Altichiero in the Fifteenth Century John Richards Editing and peer review managed by: Claudia Hopkins, Visual Arts Research Institute Edinburgh (VARIE), Edinburgh Reviewers: Flavio Boggi, Tom Tolley Abstract Altichiero was the dominant north Italian painter of the later Trecento. In Padua, in the 1370s and early 1380s, he worked for patrons close to Petrarch and his circle and perhaps in direct contact with the poet himself. By the time of the second edition of Vasari's Vite (1568) the memory of Altichiero's work had suffered significant occlusion, and Vasari's account of him is little more than an appendix to his life of Carpaccio. Only since the later nineteenth century, and particularly in the last fifty or so years, has Altichiero's reputation been restored. It is the purpose of this paper to examine aspects of that reputation throughout the century or so after the painter's death (by April 1393). Contents Introduction Marin Sanuto and Flavio Biondo Michele Savonarola Conclusion Introduction [1] The complex polarities of fame and infamy, fame and death, contemporary reputation and posthumous glory occupied a central place in early renaissance thought, above all in that of Petrarch (1304-74). Not the least of his contributions to renaissance culture was the extension of these polarities to the lives of artists. The main thrust of his piecemeal eulogy of Giotto (1266/7-1337), pronounced in various contexts, was that the painter's reputation was founded on demonstrable substance, and therefore deserved to survive. Dante (c.1265-1321) famously chose to illustrate the shifting nature of celebrity by means of Giotto's eclipse of Cimabue (c.1240-1302) but without commenting on the justice or injustice of the transference of fame involved.1 Petrarch's concerns were rather different. -

The Evolution of Landscape in Venetian Painting, 1475-1525

THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 by James Reynolds Jewitt BA in Art History, Hartwick College, 2006 BA in English, Hartwick College, 2006 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2014 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by James Reynolds Jewitt It was defended on April 7, 2014 and approved by C. Drew Armstrong, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Kirk Savage, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Ann Sutherland Harris, Professor Emerita, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by James Reynolds Jewitt 2014 iii THE EVOLUTION OF LANDSCAPE IN VENETIAN PAINTING, 1475-1525 James R. Jewitt, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2014 Landscape painting assumed a new prominence in Venetian painting between the late fifteenth to early sixteenth century: this study aims to understand why and how this happened. It begins by redefining the conception of landscape in Renaissance Italy and then examines several ambitious easel paintings produced by major Venetian painters, beginning with Giovanni Bellini’s (c.1431- 36-1516) St. Francis in the Desert (c.1475), that give landscape a far more significant role than previously seen in comparable commissions by their peers, or even in their own work. After an introductory chapter reconsidering all previous hypotheses regarding Venetian painters’ reputations as accomplished landscape painters, it is divided into four chronologically arranged case study chapters. -

Città Ideale

Città di Vigevano VERSO EXPO 2015 CITTÀ IDEALE VERSO EXPO Si la Piazza Ducale est un splendide bijou “En date du 2 février 1494 à la évocatrice du mélange de la technologie Vigevano 2015 de la Renaissance lombarde, le château Sforzesca, je dessinai les 25 escaliers, et de l’art, le génie a travaillé comme La visite de Vigevano est toujours un des Visconti et des Sforza, qui se trouve chacun de 2/3 de la brasse et de largeur ingénieur pour le Duc, Ludovic Sforza, dit moment de grande émotion. Vigevano à côté, est la forteresse qui la protège 8” brasses (Léonard de Vinci – Manuscrit le More, pendant plus de vingt ans. Les a un cœur antique qui est resté intact et l’orne. Vigevano a une tradition H, feuille 65 v.). grands témoignages sont le château et la à partir de la Renaissance jusqu’à manufacturière liée à la mode: ici fut La présence de Léonard de Vinci sur le place ducale, qui évoquent sans aucun aujourd’hui. Ce fut le Duc de Milan, inventé le talon aiguille, on peut trouver sa territoire de Vigevano est documentée doute les dessins de la “Cité idéale”, mais Ludovic Sforza à vouloir la place ducale documentation au Musée de la chaussure; par le patrimoine culturel de manière aussi la Sforzesca avec le réseau des (Piazza Ducale): les architectes de on y fabrique encore des chaussures de pertinente, dont les origines se trouvent navires, des moulins et le Colombarone, la cour milanaise contribuèrent à sa haute qualité. A quelques kilomètres, le dans la période des Sforza. -

LCI Book Ambrosiana ING 2016 LR.Pdf

LUMEN CENTER ITALIA Srl Via Donatori del Sangue n.37 20010 Santo Stefano Ticino (MI) Italia tel. +39 02 3654 4811 [email protected] ITALY OFFICE tel. +39 02 3654 4311 [email protected] EXPORT OFFICE tel. +39 02 3654 4308 [email protected] New division by LUMEN CENTER ITALIA lights up the Veneranda Biblioteca Pinacoteca Ambrosiana NOVA LUX AT AMBROSIANA PREFACE What does not do the light! It brightens LUMEN CENTER ITALIA has caught for us In this way the Pintacoteca Ambrosiana A VIBRANT the surrounding and fills it up of shapes, the light of the sun, in order to allow us to can offer to the world of art expositions ATMOSPHERE where in the indistinct dark every differ- show our masterpieces in the best possi- an example of virtuous lighting. ence is lost. Dark and panic are all one, ble conditions, in a way that a prolonged FULL OF PATHOS and not only for children! Light and joy of exposition to light could not damage the life and moving in a comfortable and good works delivered from centuries to our ad- tidy place go at the same speed. miration. The visitor is involved in the ex- posed pictorial works, has the impression The Pinacoteca Ambrosiana is living mo- to see for the first time some rooms of the ments of intense emotion caused by a Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, discovering de- new illuminating system which enhances tails and chromatic tones which, before its artistic heritages, thanks to the gener- of this intervention, were never observed. Deep study ous interest of LUMEN CENTER ITALIA. -

Pisanello Oil Paintings

Pisanello Oil Paintings Pisanello [Italian painter, 1395-1455] Portrait of a Princess of the House of Este Oil on canvas, 46947-Pisanello-Portrait of a Princess of the House of Este.jpg Oil Painting ID: 46947 | Order the painting Portrait of Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg Oil on canvas, 46948-Pisanello-Portrait of Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg.jpg Oil Painting ID: 46948 | Order the painting Portrait of Leonello d'Este Oil on canvas, 46949-Pisanello-Portrait of Leonello d'Este.jpg Oil Painting ID: 46949 | Order the painting The Virgin and Child with Saints George and Anthony Abbot Oil on canvas, 46950-Pisanello-The Virgin and Child with Saints George and Anthony Abbot.jpg Oil Painting ID: 46950 | Order the painting Vision of St Eustace Oil on canvas, 46951-Pisanello-Vision of St Eustace.jpg Oil Painting ID: 46951 | Order the painting Total 1 page, [1] Pisanello (Nationality : Italian painter, 1395-1455) Pisanello (c. 1395 - probably 1455), known professionally as Antonio di Puccio Pisano or Antonio di Puccio da Cereto, also erroneously called Vittore Pisano by Giorgio Vasari, was one of the most distinguished painters of the 1/2 early Italian Renaissance and Quattrocento. He was acclaimed by poets such as Guarino da Verona and praised by humanists of his time who compared him to such illustrious names as Cimabue, Phidias and Praxiteles. Pisanello is known for his resplendent frescoes in large murals, elegant portraits, small easel pictures, and many brilliant drawings. He is the most important commemorative portrait medallist in the first half of the 15th century. He was employed by the Doge of Venice, the Pope in the Vatican and the courts of Verona, Ferrara, Mantua, Milan, Rimini, and by the King of Naples. -

Uccello's Fluttering Monument to Hawkwood, with Schwob and Artaud

Uccello’s Fluttering Monument to Hawkwood , with Schwob and Artaud Javier Berzal De Dios diacritics, Volume 44, Number 2, 2016, pp. 86-103 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/dia.2016.0009 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/655254 Access provided by your local institution (9 Jun 2017 10:01 GMT) UCCELLO’S FLUTTERING MONUMENT TO HAWKWOOD, WITH SCHWOB AND ARTAUD JAVIER BERZAL DE DIOS Anachronism is not, in history, something that must be absolutely banished . but rather something that must be negotiated, debated, and perhaps even turned to advantage. —Georges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images At the waning of the nineteenth century, the French symbolist writer Marcel Schwob Javier Berzal de Dios is an assistant portrayed the painter Paolo Uccello (c. 1397–1475) in his Vies imaginaires (Imaginary professor at Western Washington University. He holds a PhD in art history Lives): “he could never remain in a single place; he wanted to glide, in his flight, over from the Ohio State University and an the tops of all places.”1 Schwob’s book purposefully departs from historically rigorous MA in philosophy from the City Univer- inquiries, presenting a motley collection of fictionalized biographies of real and imagi- sity of New York, Queens College. His research has been featured in Sixteenth nary characters that encompasses Lucretius, Pocahontas, William Kidd, and Sufrah, who Century Journal, SubStance, and Renais- he claims is a sorcerer in the story of Aladdin. In his chapter on Uccello (notably the sance and Reformation/Renaissance et only visual artist in the book), Schwob neglects common biographical remarks. -

Pietro Cesare Marani

▪ ▪ Pietro Cesare Marani Professore straordinario di Storia dell'arte moderna nel Politecnico di Milano. E' stato Direttore della Soprintendenza per i Beni artistici e storici di Milano, vice-direttore della Pinacoteca di Brera e condirettore del restauro del Cenacolo di Leonardo da Vinci dal 1992 al 1999. Presidente dell'Ente Raccolta Vinciana ( fondata nel 1905 ) e membro della Commissione Nazionale Vinciana per la pubblicazione dei disegni e dei manoscritti di Leonardo, Roma ( fondata nel 1903 ). Ha al suo attivo oltre duecento pubblicazioni, tradotte in otto lingue ( inglese, francese, tedesco, spagnolo, portoghese, finlandese, svedese e giapponese ), molte delle quali su Leonardo da Vinci, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Bergognone, Bernardino Luini, Bramantino e, in genere, sull'arte e l'architettura del Rinascimento italiano, la museologia e il restauro. Ha pubblicato nel 2006 ( con Rosanna Pavoni ) il volume "Musei. Trasformazioni di un'istituzione dall'età moderna al contemporaneo" per l'Editore Marsilio di Venezia. Ha collaborato alla catalogazione scientifica dei maggiori musei di Milano ( Pinacoteca di Brera, Pinacoteca del Castello Sforzesco, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, Quadreria dell'Arcivescovado )ed è stato il curatore del catalogo dei dipinti del Museo Bagatti Valsecchi. Con B.Fabjan ha curato inoltre il Catalogo generale del Museo della Certosa di Pavia. Ha pubblicato il Catalogo dei disegni di Leonardo da Vinci e della sua cerchia nelle Collezioni pubbliche in Francia ( Edito sotto l'egida della Commissione Nazionale Vinciana -

La Cultura Figurativa a Pavia Nell'età Di Leonardo E Le Raccolte Civiche

Da Foppa a Giampietrino: LEONARDESCHI dipinti dal Museo Statale Ermitage di San Pietroburgo e dai Musei Civici di Pavia Pavia, Castello Visconteo 20 marzo - 10 luglio 2011 LA CULTURA FIGURATIVA A PAVIA NELL’ETÀ DI LEONARDO E LE RACCOLTE CIVICHE di Susanna Zatti Nella primavera del 1952 il Castello visconteo di Pavia aveva ospitato la mostra Arte e ambiente pavese al tempo di Leonardo, organizzata dal Comitato nazionale di onoranze a Leonardo nel V centenario della nascita. Erano stati allora esposti vari materiali d’arte provenienti da collezioni pubbliche e private, tra cui ceramiche, sculture, manoscritti, disegni, smalti, miniature. Un particolare rilievo era destinato ai dipinti di artisti dell’età e della cerchia del sommo maestro - tavole e pale di V.Foppa, A.Bergognone, Giampietrino, B.Luini, A.Solario, B.Lanzani, B.De Conti - richiesti in prestito dalla Pinacoteca di Brera di Milano, dai Musei di Brescia, dalla Certosa e da chiese pavesi, oltre che provenienti dalle raccolte dei Musei Civici. La mostra odierna restringe il campo alla pittura e focalizza l’interesse sulle opere di quegli artisti che nelle collezioni russe dell’Ermitage sono qualifi cati come “leonardeschi” e affi anca a loro, mettendoli in confronto e a colloquio, sia tavole e tele di quei medesimi autori possedute dai Musei pavesi, sia altri dipinti pervenuti alle collezioni civiche nel corso del XIX secolo con attribuzione a Leonardo e alla sua maniera, vuoi per la cifra stilistica, vuoi per l’iconografi a: dipinti che sono stati poi confermati dagli studi più recenti quali pertinenti a quella felice e feconda temperie culturale che caratterizzò, nella seconda metà del Quattrocento e nei primi decenni del Cinquecento, il territorio del Ducato visconteo-sforzesco (e si ricordi che Pavia era il secondo centro per importanza). -

May 9 Through September 10, 2017

SUMMER EXHIBITION CELEBRATES THE LARGEST ACQUISITION IN THE FRICK COLLECTION’S HISTORY THE PURSUIT OF IMMORTALITY: MASTERPIECES FROM THE SCHER COLLECTION OF PORTRAIT MEDALS May 9 through September 10, 2017 Over the course of six decades, Stephen K. Scher—a collector, scholar, and curator—has assembled the most comprehensive and significant private collection of portrait medals in the world, part of which he and his wife, Janie Woo Scher, gave to The Frick Collection last year. To celebrate the Schers’ generous gift of what is the largest acquisition in the museum’s history, the Frick presents more than one hundred of the finest examples from their collection in The Pursuit of Immortality, on view from May 9 through September 10, 2017. The exhibition is Pierre-Jean David d’Angers (1788–1856), Josephine organized by Aimee Ng, Associate Curator, The Frick Collection, and Stephen K. Bonaparte, ca. 1832, gilt copper alloy (cast), Scher Collection, promised gift to The Frick Collection Scher. Comments Director Ian Wardropper, “Henry Clay Frick had an abiding interest in portraiture as expressed in the paintings, sculpture, enamels, and works on paper he acquired. The Scher medals will coalesce beautifully with these holdings, being understood in our galleries within the broader contexts of European art and culture. At the same time, the intimate scale of the institution will offer a superb platform for the medals to be appreciated as an independent art form, one long overdue for fresh attention and public appreciation.” The exhibition, to take place in the lower-level galleries, showcases superlative examples from Italy, Germany, France, the Netherlands, England, and other regions together with related sculptures and works on paper from the Frick’s permanent collection, helping to illuminate the place of medals Antonio di Puccio Pisano, called Pisanello (ca.