Understanding Asset Values: Stock Prices, Exchange Rates, and the “Peso Problem”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Market Peso Exchange As a Mechanism to Place Substantial Amounts of Currency from U.S

United States Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network FinCEN Advisory Subject: This advisory is provided to alert banks and other depository institutions Colombian to a large-scale, complex money laundering system being used extensively by Black Market Colombian drug cartels to launder the proceeds of narcotics sales. This Peso Exchange system is affecting both U.S. financial depository institutions and many U.S. businesses. The information contained in this advisory is intended to help explain how this money laundering system works so that U.S. financial institutions and businesses can take steps to help law enforcement counter it. Overview Date: November Drug sales in the United States are estimated by the Office of National 1997 Drug Control Policy to generate $57.3 billion annually, and most of these transactions are in cash. Through concerted efforts by the Congress and the Executive branch, laws and regulatory actions have made the movement of this cash a significant problem for the drug cartels. America’s banks have effective systems to report large cash transactions and report suspicious or Advisory: unusual activity to appropriate authorities. As a result of these successes, the Issue 9 placement of large amounts of cash into U.S. financial institutions has created vulnerabilities for the drug organizations and cartels. Efforts to avoid report- ing requirements by structuring transactions at levels well below the $10,000 limit or camouflage the proceeds in otherwise legitimate activity are continu- ing. Drug cartels are also being forced to devise creative ways to smuggle the cash out of the country. This advisory discusses a primary money laundering system used by Colombian drug cartels. -

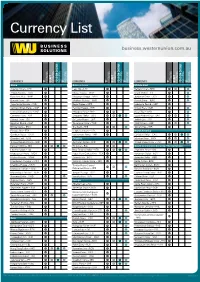

View Currency List

Currency List business.westernunion.com.au CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING CURRENCY TT OUTGOING DRAFT OUTGOING FOREIGN CHEQUE INCOMING TT INCOMING Africa Asia continued Middle East Algerian Dinar – DZD Laos Kip – LAK Bahrain Dinar – BHD Angola Kwanza – AOA Macau Pataca – MOP Israeli Shekel – ILS Botswana Pula – BWP Malaysian Ringgit – MYR Jordanian Dinar – JOD Burundi Franc – BIF Maldives Rufiyaa – MVR Kuwaiti Dinar – KWD Cape Verde Escudo – CVE Nepal Rupee – NPR Lebanese Pound – LBP Central African States – XOF Pakistan Rupee – PKR Omani Rial – OMR Central African States – XAF Philippine Peso – PHP Qatari Rial – QAR Comoros Franc – KMF Singapore Dollar – SGD Saudi Arabian Riyal – SAR Djibouti Franc – DJF Sri Lanka Rupee – LKR Turkish Lira – TRY Egyptian Pound – EGP Taiwanese Dollar – TWD UAE Dirham – AED Eritrea Nakfa – ERN Thai Baht – THB Yemeni Rial – YER Ethiopia Birr – ETB Uzbekistan Sum – UZS North America Gambian Dalasi – GMD Vietnamese Dong – VND Canadian Dollar – CAD Ghanian Cedi – GHS Oceania Mexican Peso – MXN Guinea Republic Franc – GNF Australian Dollar – AUD United States Dollar – USD Kenyan Shilling – KES Fiji Dollar – FJD South and Central America, The Caribbean Lesotho Malati – LSL New Zealand Dollar – NZD Argentine Peso – ARS Madagascar Ariary – MGA Papua New Guinea Kina – PGK Bahamian Dollar – BSD Malawi Kwacha – MWK Samoan Tala – WST Barbados Dollar – BBD Mauritanian Ouguiya – MRO Solomon Islands Dollar – -

Colombian Peso Forecast Special Edition Nov

Friday Nov. 4, 2016 Nov. 4, 2016 Mexican Peso Outlook Is Bleak With or Without Trump Buyside View By George Lei, Bloomberg First Word The peso may look historically very cheap, but weak fundamentals will probably prevent "We're increasingly much appreciation, regardless of who wins the U.S. election. concerned about the The embattled currency hit a three-week low Nov. 1 after a poll showed Republican difference between PDVSA candidate Donald Trump narrowly ahead a week before the vote. A Trump victory and Venezuela. There's a could further bruise the peso, but Hillary Clinton wouldn't do much to reverse 26 scenario where PDVSA percent undervaluation of the real effective exchange rate compared to the 20-year average. doesn't get paid as much as The combination of lower oil prices, falling domestic crude production, tepid economic Venezuela." growth and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio are key challenges Mexico must address, even if — Robert Koenigsberger, CIO at Gramercy a status quo in U.S. trade relations is preserved. Oil and related revenues contribute to Funds Management about one third of Mexico's budget and output is at a 32-year low. Economic growth is forecast at 2.07 percent in 2016 and 2.26 percent in 2017, according to a Nov. 1 central bank survey. This is lower than potential GDP growth, What to Watch generally considered at or slightly below 3 percent. To make matters worse, Central Banks Deputy Governor Manuel Sanchez said Oct. Nov. 9: Mexico's CPI 21 that the GDP outlook has downside risks and that the government must urgently Nov. -

Argentina's 2001 Economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for Europe

Argentina’s 2001 economic and Financial Crisis: Lessons for europe Former Under Secretary of Finance and Chief Advisor to the Minister of the Miguel Kiguel Economy, Argentina; Former President, Banco Hipotecario; Director, Econviews; Professor, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella he 2001 Argentine economic and financial banks and international reserves—was not enough crisis has many parallels with the problems to cover the financial liabilities of the consolidated Tthat some European countries are facing to- financial system . This was a major source of vulner- day . Prior to the crisis, Argentina was suffering a ability, especially because there is ample evidence deep recession, large levels of debt, twin deficits in that an economy without a lender of last resort is the fiscal and current accounts, and the country inherently unstable and subject to bank runs . This had an overvalued currency but devaluation was is not a pressing issue in Europe, where the Euro- not an option . pean Central Bank can provide liquidity to banks . Argentina tried in vain to restore its competitive- The trigger for the crisis in Argentina was a run on ness through domestic deflation and improving the banking system as people realized that there its solvency by increasing its fiscal accounts in were not enough dollars in the system to cover all the midst of a recession . The country also tried to the deposits . As the run intensified, the Argentine avoid a default first by resorting to a large financial government was forced to introduce a so-called package from the multilateral institutions (the so “fence” to control the outflow of deposits . -

The Cuban Convertible Peso

The Cuban Convertible Peso A Redefinitionof Dependence MARK PIPER T lie story of Cuba’s achievement of nationhood and its historical economic relationship with the United States is an instructive example of colonialism and neo-colonial dependence. From its conquest in 1511 until 1898. Cuba was a colony of the Spanish Crown, winning independence after ovo bloody insurgencies. Dtiring its rise to empire, the U.S. acquired substantial economic interest on the island and in 1898 became an active participant in the ouster of the governing Spanish colonial power. As expressed in his poem Nuesrra America,” Ctiban nationalist José Marti presciently feared that the U.S. participation w’ould lead to a new type ofcolonialism through ctiltural absorption and homogenization. Though the stated American goal of the Spanish .Arncrican Var was to gain independence for Cuba, after the Spanish stirrender in July 189$ an American military occupation of Cuba ensued. The Cuban independence of May1902 vas not a true independence, but by virtue of the Platt Amendmentw’as instead a complex paternalistic neo-eolonial program between a dominant American empire and a dependent Cuban state. An instrument ot the neo colonial program tvas the creation of a dependent Cuban economy, with the imperial metropole economically dominating its dependent nation-state in a relationship of inequality. i’o this end, on 8 December 189$, American president William McKinley isstied an executive order that mandated the usc of the U.S. dollar in Cuba and forced the withdrawing from circulation of Spanish colonial currency.’ An important hallmark for nationalist polities is the creation of currency. -

The Giant Sucking Sound: Did NAFTA Devour the Mexican Peso?

J ULY /AUGUST 1996 Christopher J. Neely is a research economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Kent A. Koch provided research assistance. This article examines the relationship The Giant between NAFTA and the peso crisis of December 1994. First, the provisions of Sucking Sound: NAFTA are reviewed, and then the links between NAFTA and the peso crisis are Did NAFTA examined. Despite a blizzard of innuendo and intimation that there was an obvious Devour the link between the passage of NAFTA and Mexican Peso? the peso devaluation, NAFTA’s critics have not been clear as to what the link actually was. Examination of their argu- Christopher J. Neely ments and economic theory suggests two possibilities: that NAFTA caused the Mex- t the end of 1993 Mexico was touted ican authorities to manipulate and prop as a model for developing countries. up the value of the peso for political rea- A Five years of prudent fiscal and mone- sons or that NAFTA’s implementation tary policy had dramatically lowered its caused capital flows that brought the budget deficit and inflation rate and the peso down. Each hypothesis is investi- government had privatized many enter- gated in turn. prises that were formerly state-owned. To culminate this progress, Mexico was preparing to enter into the North American NAFTA Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with NAFTA grew out of the U.S.–Canadian Canada and the United States. But less than Free Trade Agreement of 1988.1 It was a year later, in December 1994, investors signed by Mexico, Canada, and the United sold their peso assets, the value of the Mex- States on December 17, 1992. -

Causes and Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis

Causes and Lessons of the Mexican Peso Crisis Stephany Griffith-Jones IDS, University of Sussex May 1997 This study has been prepared within the UNU/WIDER project on Short- Term Capital Movements and Balance of Payments Crises, which is co- directed by Dr Stephany Griffith-Jones, Fellow, IDS, University of Sussex; Dr Manuel F. Montes, Senior Research Fellow, UNU/WIDER; and Dr Anwar Nasution, Consultant, Center for Policy and Implementation Studies, Indonesia. UNU/WIDER gratefully acknowledges the financial contribution to the project by the Government of Sweden (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency - Sida). CONTENTS List of tables and charts iv Acknowledgements v Abstract vi I Introduction 1 II The apparently golden years, 1988 to early 1994 6 III February - December 1994: The clouds darken 15 IV The massive financial crisis explodes 24 V Conclusions and policy implications 31 Bibliography 35 iii LIST OF TABLES AND CHARTS Table 1 Composition (%) of Mexican and other countries' capital inflows, 1990-93 8 Table 2 Mexico: Summary capital accounts, 1988-94 10 Table 3 Mexico: Non-resident investments in Mexican government securities, 1991-95 21 Table 4 Mexico: Quarterly capital account, 1993 - first quarter 1995 (in millions of US dollars) 22 Table 5 Mexican stock exchange (BMV), 1989-1995 27 Chart 1 Mexico: Real effective exchange rate (1980=100) 7 Chart 2 Current account balance (% of GDP) 11 Chart 3 Saving-investment gap and current account 12 Chart 4 Stock of net international reserves in 1994 (in millions of US dollars) 17 Chart 5 Mexico: Central bank sterilised intervention 18 Chart 6 Mexican exchange rate changes within the exchange rate band (November 1991 through mid-December 1994) 19 Chart 7 Mexican international reserves and Tesobonos outstanding 20 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank UNU/WIDER for financial support for this research which also draws on work funded by SIDA and CEPAL. -

The Chilean Peso Exchange-Rate Carry Trade and Turbulence

The Chilean peso exchange-rate carry trade and turbulence Paulo Cox and José Gabriel Carreño Abstract In this study we provide evidence regarding the relationship between the Chilean peso carry trade and currency crashes of the peso against other currencies. Using a rich dataset containing information from the local Chilean forward market, we show that speculation aimed at taking advantage of the recently large interest rate differentials between the peso and developed- country currencies has led to several episodes of abnormal turbulence, as measured by the exchange-rate distribution’s skewness coeffcient. In line with the interpretative framework linking turbulence to changes in the forward positions of speculators, we fnd that turbulence is higher in periods during which measures of global uncertainty have been particularly high. Keywords Currency carry trade, Chile, exchange rates, currency instability, foreign-exchange markets, speculation JEL classification E31, F41, G15, E24 Authors Paulo Cox is a senior economist in the Financial Policy Division of the Central Bank of Chile. [email protected]. José Gabriel Carreño is with the Financial Research Group of the Financial Policy Division of the Central Bank of Chile. [email protected] 72 CEPAL Review N° 120 • December 2016 I. Introduction Between 15 and 23 September 2011, the Chilean peso depreciated against the United States dollar by about 8.2% (see fgure 1). The magnitude of this depreciation was several times greater than the average daily volatility of the exchange rate for these currencies between 2002 and 2012.1 No events that would affect any fundamental factor that infuences the price relationship between these currencies seems to have occurred that would trigger this large and abrupt adjustment. -

Monetary and Exchange Rate Reform in Cuba: Lessons from Vietnam

Monetary and Exchange Rate Reform in Cuba: Lessons from Vietnam Pavel Vidal Alejandro Acknowledgements I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to IDE/JETRO for making possible my stay in Japan in 2011 and this research, which has been very important for my career and may contribute to the economic changes that are happening in Cuba at present. The advice of IDE researchers during my investigation process and presentations in seminars were very constructive, since they were both honest and thoughtful; I appreciate this enormously. Particular thanks are due to Mai Fujita, Nguyen Quoc Hung and all the people of the Latin American Studies Group. I express my gratitude to the staff of the VRF Program, especially Takao Tsuneishi and Kenji Marusaki. Three exceptional colleagues and friends, Kanako Yamaoka (my counterpart at IDE), Michihiro Sindo and Takashi Tanaka, as well as their family and friends, contributed not only to my research but to enriching my knowledge of the unique Japanese cultural context. Thanks to them I sometimes felt as if I were at home. I do not want to forget to mention the attentions and affection of Tomoko Murai from the IDE library. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the support of the Social Science Research Council (New York) for allowing me to visit Vietnam in 2010. Firsthand information and impressions I received from that study tour have been vital for this research. i Index of Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................... -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

Q&A on the Exchange Rate Impact

Q&A ON THE EXCHANGE RATE IMPACT: HOW MUCH, WHAT WE CAN DO, AND WHAT ’S NEXT In general, a firm currency is welcome news as it reflects positive developments in the country’s economic fundamentals, In 2007, as the Philippine economy grew at its fastest rate in 31 years, the Philippine peso emerged as one of the top performing currencies in Asia and hit a 7 ½-year high of P41/US$1 in December 2007. For Filipino consumers, a firmer peso meant lower prices in peso terms for imported goods and services. For instance, a stronger peso shielded the Philippines from the full impact of record high world oil prices. Based on our estimates, prices of oil products would have been higher by about P2.00 per liter if the peso had not appreciated against the US dollar. This would have raised transport fares and consequently food prices as well for Filipino consumers. On the other hand, for sectors whose earnings are denominated in US dollars, a firmer peso is not a positive development. This includes exporters as well as overseas Filipinos and their dependents who now receive less pesos for every dollar they exchange. Given this, discussions have been divided on whether a firm peso is ultimately a positive or a negative for our country. It is in this context that we saw the need for this series of Questions & Answers. We hope that through this, we are able to promote better understanding of issues related to exchange rate developments and the government’s policy responses to these issues. -

International Currencies and Dollarization

1 International Currencies and Dollarization Alberto Trejos∗ Introduction The dollar has become an international currency, used frequently in ordinary domestic transactions outside the US. The extent to which the smaller countries in Latin America have “dollarized” is fairly striking. For example, in Costa Rica’s banking system, 61% of the credit assets and 53% of the interest bearing liabilities are denominated in dollars. Focusing on media of exchange rather than stores of value, 26% of checking account deposits and (less precisely) 30% of cash are in dollars. These numbers are biased downward, as they do not include the fairly extensive use by local businesses and consumers of foreign banks and the off-shore subsidiaries of local banks. Many ads and contracts use dollars as the unit of account to post prices. The same phenomena occur in at least another dozen small Latin American countries. The process of dollarization has been relatively quick, and while it started under high inflation, it has continued under price stability. In some of these countries, there is a debate about the possibility of eliminating their local monies entirely, and using only the dollar as currency. In fact, just in the year 2000 two countries, El Salvador and Ecuador, formally made the decision to dollarize (joining Panama, that did it at the beginning of the century), and the discussion has been fairly intense in other places. If this trend continues, the question that this conference means to address (What is the future of Central Banking?) would be answered by a vision of many small countries that do not issue their own currency, a few mid-sized and large countries that do, and a handful of major Central Banks executing international monetary policy.