Jessica Lee Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Middle Ages of the City

Chapter 5 Merchants and Bowmen: Middle Ages of the City Once past, dreams and memories are the same thing. U. piersanti, L’uomo delle Cesane (1994) It’s a beautiful day in May. We find ourselves in Assisi, the city of saints Francis and Clare. The “Nobilissima parte de sopra” and the “Magnifica parte de sotto” (the Most Noble Upper Part and the Magnificent Lower Part), which represent the districts of the city’s theoretical medieval subdivision, challenge each oth- er to a series of competitions: solemn processions, feats of dexterity, songs, challenges launched in rhyme, stage shows. In this way, it renews the medieval tradition of canti del maggio (May songs), performed in the piazzas and under girls’ balconies by bands of youths wandering the city. A young woman is elect- ed Madonna Primavera (Lady Spring). We celebrate the end of winter, the return of the sun, flowers, and love. This medieval festival, resplendent with parades, flag bearers, ladies, knights, bowmen, and citizen magistrates, re- sounding with songs, tambourines, and trumpets, lasts three days and involves the entire population of Assisi, which finds itself, together with tourists and visitors, immersed in the atmosphere of a time that was. At night, when the fires and darkness move the shadows and the natural odors are strongest, the magic of the illusion of the past reaches its highest pitch: Three nights of May leave their mark on our hearts Fantasy blends with truth among sweet songs And ancient history returns to life once again The mad, ecstatic magic of our feast.1 Attested in the Middle Ages, the Assisan Calendimaggio (First of May) reap- peared in 1927 and was interrupted by the Second World War, only to resume in 1947. -

Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews

"Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews, (1882-1965)" By Maddalena Marinari University of Kansas, 2009 B.A. Istituto Universitario Orientale Submitted to the Department of History and the Faculty of The Graduate School of the University Of Kansas in partial fulfillment of The requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________________ Dr. Jeffrey Moran, Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Gabaccia __________________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani __________________________________________ Dr. Roberta Pergher __________________________________________ Dr. Ruben Flores Date Defended: 14 December 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Maddalena Marinari certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "Liberty, Restriction, and the Remaking of Italians and Eastern European Jews, (1882-1965)" Committee: __________________________________________ Dr. Jeffrey Moran, Chair __________________________________________ Dr. Donna Gabaccia __________________________________________ Dr. Sheyda Jahanbani __________________________________________ Dr. Roberta Pergher __________________________________________ Dr. Ruben Flores Date Approved: 14 December 2009 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………….3 Chapter 1: From Unwanted to Restricted (1890-1921) ………………………………………...17 Chapter 2: "The doors of America are worse than shut when they are half-way open:" The Fight against the Johnson-Reed Immigration -

QUALESTORIA. Rivista Di Storia Contemporanea. L'italia E La

«Qualestoria» n.1, giugno 2021, pp. 163-186 DOI: 10.13137/0393-6082/32191 https://www.openstarts.units.it/handle/10077/21200 163 Culture, arts, politics. Italy in Ivan Meštrović’s and Bogdan Radica’s discourses between the two World Wars di Maciej Czerwiński In this article the activity and discourses of two Dalmatian public figures are taken into consideration: the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and the journalist Bogdan Radica. They both had an enormous influence on how the image of Italy was created and disseminated in Yugoslavia, in particular in the 1920s and 1930s. The analysis of their discourses is interpreted in terms of the concept of Dalmatia within a wider Mediterranean basin which also refers to two diverse conceptualizations of Yugoslavism, cultural and politi- cal. Meštrović’s vision of Dalmatia/Croatia/Yugoslavia was based on his rural hinterland idiom enabling him to embrace racial and cultural Yugoslavism. In contrast, Radica, in spite of having a pro-Yugoslav orientation during the same period, did not believe in race, so for him the idea of Croat-Serb unity was more a political issue (to a lesser extent a cultural one). Keywords: Dalmatia, Yugoslav-Italian relationships, Croatianness, Yugoslavism, Bor- derlands Parole chiave: Dalmazia, Relazioni Jugoslavia-Italia, Croaticità, Jugoslavismo, Aree di confine Introduction This article takes into consideration the activity and discourses of the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and the journalist Bogdan Radica1. The choice of these two figures from Dalmatia, though very different in terms of their profession and political status in the interwar Yugoslav state (1918-41), has an important justification. Not only they both were influenced by Italian culture and heritage (displaying the typical Dalmatian ambivalence towards politics), but they also evaluated Italian heritage and politics in the Croatian/Yugoslav public sphere. -

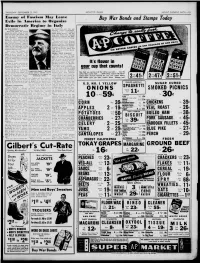

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Film Film Film Film

Annette Michelson’s contribution to art and film criticism over the last three decades has been un- paralleled. This volume honors Michelson’s unique C AMERA OBSCURA, CAMERA LUCIDA ALLEN AND TURVEY [EDS.] LUCIDA CAMERA OBSCURA, AMERA legacy with original essays by some of the many film FILM FILM scholars influenced by her work. Some continue her efforts to develop historical and theoretical frame- CULTURE CULTURE works for understanding modernist art, while others IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION practice her form of interdisciplinary scholarship in relation to avant-garde and modernist film. The intro- duction investigates and evaluates Michelson’s work itself. All in some way pay homage to her extraordi- nary contribution and demonstrate its continued cen- trality to the field of art and film criticism. Richard Allen is Associ- ate Professor of Cinema Studies at New York Uni- versity. Malcolm Turvey teaches Film History at Sarah Lawrence College. They recently collaborated in editing Wittgenstein, Theory and the Arts (Lon- don: Routledge, 2001). CAMERA OBSCURA CAMERA LUCIDA ISBN 90-5356-494-2 Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson EDITED BY RICHARD ALLEN 9 789053 564943 MALCOLM TURVEY Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida Camera Obscura, Camera Lucida: Essays in Honor of Annette Michelson Edited by Richard Allen and Malcolm Turvey Amsterdam University Press Front cover illustration: 2001: A Space Odyssey. Courtesy of Photofest Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 494 2 (paperback) nur 652 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2003 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

The Chronicle of Dino Compagni / Translated by Else C. M. Benecke

#m hbl.stx DG 737.2.C613 le i?mnP/!f? of Dino Compagni / 3 1153 0DSMS117 t, % n WRITTEN •T$' FIRST PRINTED • IN • 1726- PLEASE NOTE It has been necessary to replace some of the original pages in this book with photocopy reproductions because of damage or mistreatment by a previous user. Replacement of damaged materials is both expensive and time-consuming. Please handle this volume with care so that information will not be lost to future readers. Thank you for helping to preserve the University's research collections. THE TEMPLE CLASSICS THE CHRONICLE OF DINO COMPAGNI Digitized'by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/chronicleofdinocOOcomp mmyi CHRPNICE 92DINO COMPAGNI TRANSITED ^ELSE CM. BENECKE S§ FERRERS HOWELL MDCCCCVI PUBL15H6D- BY-^M D6NT- •AMP-CO : ALDlNe-HOUSe-LOMDON-W-O PRELIMINARY NOTE vii PRELIMINARY NOTE Though Dino Compagni calls his work a Chronicle, it is not (like Giovanni Villani's, for example) a Chronicle in the sense in which the term is now used to express a particular kind of narration dis- " tinguished from a history ; the terms " chronicle and "history" being in Dino's time interchange- able. Dino's book is in form the history of a particular fact, namely, the division of the Guelf party in Florence into the White and the Black Guelfs, with its attendant circumstances, its causes, and its results : but under this form is unfolded at the same time the history of the steps by which the wealthy traders of Florence (jfropolani, popolani grassi, and collectively popolo grasso) organised in the greater guilds (see Appendix II.) acquired and retained the control of the machinery of govern- ment in the city and its outlying territory (contado), excluding (practically) from all participation therein on the one hand the Magnates (i.e. -

Sicily and the Surrender of Italy

United States Army in World War II Mediterranean Theater of Operations Sicily and the Surrender of Italy by Albert N. Garland and Howard McGaw Smyth Assisted by Martin Blumenson CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY UNITED STATES ARMY WASHINGTON, D.C., 1993 Chapter XIV The Climax Sardinia Versus the Mainland The successful invasion of Sicily clarified strategic problems and enabled the Allies to turn from debate to decision. The Combined Chiefs of Staff at the TRIDENT Conference in May had directed General Eisenhower to knock Italy out of the war and contain the maximum number of German forces, but they had not told him how. Preparing to launch operations beyond the Sicilian Campaign, AFHQ had developed several outline plans: BUTTRESS, invasion of the Italian toe by the British 10 Corps; GOBLET, a thrust at the ball of the Italian foot by the British 5 Corps; BRIMSTONE, invasion of Sardinia; and FIREBRAND, invasion of Corsica. But a firm decision on the specific course of action to be taken was still lacking.1 The four plans, Eisenhower had explained to Churchill during the Algiers meetings in June, pointed to two broad alternative courses. If the Axis resisted vigorously in Sicily, thereby forecasting high Italian morale and a bitter and protracted struggle for the Allies, then BRIMSTONE and FIREBRAND, insular operations, were preferable. Otherwise, operations on the Italian mainland were more promising. Despite Churchill's articulate enthusiasm for the latter course, Eisenhower had made no commitment. He awaited the factual evidence to be furnished in Sicily. Meanwhile, the Americans and British continued to argue over strategy. -

Italian/Americans and the American Racial System: Contadini to Settler Colonists?

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Italian/Americans and the American Racial System: Contadini to Settler Colonists? Stephen J. Cerulli The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3178 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ITALIAN/AMERICANS AND THE AMERICAN RACIAL SYSTEM: CONTADINI TO SETTLER COLONISTS? by Stephen J. Cerulli A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2019 i Italian/Americans and the American Racial System: Contadini to Settler Colonists? by Stephen J. Cerulli This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Date George Fragopoulos Thesis Advisor Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK ii ABSTRACT Italian/Americans and the American Racial System: Contadini to Settler Colonists? by Stephen J. Cerulli Advisor: George Fragopoulos This thesis explores the relationship between ethnicity and race, “whiteness,” in the American racial system through the lens of Italian/Americans. Firstly, it overviews the current scholarship on Italian/Americans and whiteness. Secondly, it analyzes methodologies that are useful for understanding race in an American context.