“. . . Not So Bad As Some Say”: Ney at Quatre Bras

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter VI the Strategic Stalemate from End of August to Mid-October 1812

Chapter VI The Strategic Stalemate from End of August to mid-October 1812 “The Daily Life” ollowing wounds received on For his part, Wittgenstein was August 17th, Oudinot was also forced to inaction because of the F evacuated to Vilna and it was weakness of its Corps. It can be Gouvion St. Cyr who took command estimated that the Russian general the next day and won the battle. For had under his command, on the his victory on the 18th, he was evening of August 18, barely 12,000 appointed Marshal of the Empire by infantrymen, 2,200 horsemen and decree of August 27th, 1812. General 1,400 artillerymen. Because of the Maison, will be appointed general de weakness of his battalions, he will division on August 21st and will take have to reorganize them. For example, the head of the 8th infantry division. on August 25th, the six depot After the relatively shallow battalions of Grenadiers were merged attempt to pursue the Russians and into three battalions (Leib and the fighting of August 23rd, where the Arakseiev together, St Petersburg and Bavarian general Siebein was mortally Tauride, Pavlov and Ekaterinoslav). wounded, St. Cyr will remain quite The forces of Wittgenstein will inactive, concentrating his two corps increase quite regularly until the of army on Polotsk and its vicinity. His beginning of October: thanks to the forces declining steadily, he will return of the wounded, first; the strengthen (but with delay) his arrival of men from the depot of the positions by building some redoubts, regiments belonging to the 1st Corps, trying to form a sort of entrenched afterwards; and also because of the camp in front of the walls of Polotsk. -

Wellingtons Peninsular War Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WELLINGTONS PENINSULAR WAR PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julian Paget | 288 pages | 01 Jan 2006 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9781844152902 | English | Barnsley, United Kingdom Wellingtons Peninsular War PDF Book In spite of the reverse suffered at Corunna, the British government undertakes a new campaign in Portugal. Review: France '40 Gold 16 Jan 4. Reding was killed and his army lost 3, men for French losses of 1, Napoleon now had all the pretext that he needed, while his force, the First Corps of Observation of the Gironde with divisional general Jean-Andoche Junot in command, was prepared to march on Lisbon. VI, p. At the last moment Sir John had to turn at bay at Corunna, where Soult was decisively beaten off, and the embarkation was effected. In all, the episode remains as the bloodiest event in Spain's modern history, doubling in relative terms the Spanish Civil War ; it is open to debate among historians whether a transition from absolutism to liberalism in Spain at that moment would have been possible in the absence of war. On 5 May, Suchet besieged the vital city of Tarragona , which functioned as a port, a fortress, and a resource base that sustained the Spanish field forces in Catalonia. The move was entirely successful. Corunna While the French were victorious in battle, they were eventually defeated, as their communications and supplies were severely tested and their units were frequently isolated, harassed or overwhelmed by partisans fighting an intense guerrilla war of raids and ambushes. Further information: Lines of Torres Vedras. The war on the peninsula lasted until the Sixth Coalition defeated Napoleon in , and it is regarded as one of the first wars of national liberation and is significant for the emergence of large-scale guerrilla warfare. -

The Age of Napoleon & the Triumph of Romanticism Chapter 20

The Age of Napoleon & the Triumph of Romanticism Chapter 20 The Rise of Napoleon - Chief danger to the Directory came from royalists o Émigrés returned to France o Spring 1797 – royalists won elections o To preserve the Republic . Directory staged a coup d’etat (Sept. 4, 1797) Placed their supporters back in power - Napoleon o Born 1769 on the island of Corsica . Went to French schools . Pursued military career 1785 – artillery officer . favored the revolution was a fiery Jacobin . 1793- General - Early military victories o Crushed Austria and Sardinia in Italy . Made Treaty of Camp Formino in Oct 1797 on his own accord Returned to France a hero - Britain . Only remaining enemy Too risky to cross channel o Chose to attack in Egypt . Wanted to cut off English trade and communication with India Failure - Russia Alarmed . 2nd coalition formed in 1799 Russia, Ottomans, Austria, Britain o Beat French in Italy and Switzerland 1 Constitution Year VII - Economic troubles and international situation o Directory lost support o Abbe Sieyes, proposed a new constitution . Wanted a strong executive Would require another coup d’etat o October 1799 . Napoleon left army in Egypt November 10, 1799 o Successful coup Napoleon issued the Constitution in December (Year VIII) o First Consul The Consulate in France (1799-1804) - Closed the French Revolution - Achieved wealth and property opportunities o Napoleon’s constitution was voted in overwhelmingly - Napoleon made peace with French enemies o 1801 Treaty of Luneville – took Austria out of war o 1802 Treaty of Amiens – peace with Britain o Peace at home . Employed all political factions (if they were loyal) . -

Pierre Riel, the Marquis De Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte's Spanish Policy, 1802-05 Michael W

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Fear and Domination: Pierre Riel, the Marquis de Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte's Spanish Policy, 1802-05 Michael W. Jones Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Fear and Domination: Pierre Riel, the Marquis de Beurnonville at the Spanish Court and Napoleon Bonaparte’s Spanish Policy, 1802-05 By Michael W. Jones A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester 2005 Copyright 2004 Michael W. Jones All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approved the dissertation of Michael W. Jones defended on 28 April 2004. ________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Outside Committee Member Patrick O’Sullivan ________________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ________________________________ James Jones Committee Member ________________________________ Paul Halpern Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my father Leonard William Jones and my mother Vianne Ruffino Jones. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Earning a Ph.D. has been the most difficult task of my life. It is an endeavor, which involved numerous professors, students, colleagues, friends and family. When I started at Florida State University in August 1994, I had no comprehension of how difficult it would be for everyone involved. Because of the help and kindness of these dear friends and family, I have finally accomplished my dream. -

Marshal Louis Nicolas Devout in the Historiography of the Battle of Borodino

SHS Web of Conferences 106, 04006 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/202110604006 MTDE 2021 Marshal louis Nicolas devout in the historiography of the battle of Borodino Francesco Rubini* Academy of Engineering, Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia, School of Historical Studies, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, Russian Federation Abstract. This article is dedicated to the study and analysis of the historiography about the participation of Marshal Davout during the Battle of Borodino of 1812. The article analyzes a number of sources of both personal and non-personal nature and the effect of the event on art. In the work are offered by the author professional translations of several extracts of historiography which have never been translated from Russian, and which are therefore still mostly unknown to the international scientific community. In addition, the article provides some statistical data on the opinion of contemporaries on the results of the Patriotic War of 1812. 1 Introduction «Скажи-ка, дядя, ведь не даром «Hey tell, old man, had we a cause Москва, спаленная пожаром, When Moscow, razed by fire, once was Французу отдана? Given up to Frenchman's blow? Ведь были ж схватки боевые, Old-timers talk about some frays, Да, говорят, еще какие! And they remember well those days! Недаром помнит вся Россия With cause all Russia fashions lays Про день Бородина!» About Borodino!». The battle of Borodino, which took place during the Russian Campaign of 1812, is without any doubt one of the most important and crucial events of Russian history. Fought on the 7th of September, it was a huge large-scale military confrontation between the armed forces of the First French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon Bonaparte himself, and the Russian Army, commanded by General Mikhail Kutuzov, and is still studied as one of the bloodiest and most ferocious battles of the Napoleonic Wars. -

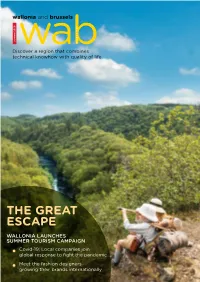

Wabmagazine Discover a Region That Combines Technical Knowhow with Quality of Life

wallonia and brussels summer 2020 wabmagazine Discover a region that combines technical knowhow with quality of life THE GREAT ESCAPE WALLONIA LAUNCHES SUMMER TOURISM CAMPAIGN Covid-19: Local companies join global response to fight the pandemic Meet the fashion designers growing their brands internationally .CONTENTS 6 Editorial The unprecedented challenge of Covid-19 drew a sharp Wallonia and Brussels - Contact response from key sectors across Wallonia. As companies as well as individuals took action to confront the crisis, www.wallonia.be their actions were pivotal for their economic survival as www.wbi.be well as the safety of their employees. For audio-visual en- terprise KeyWall, the combination of high-tech expertise and creativity proved critical. Managing director Thibault Baras (pictured, above) tells us how, with global activities curtailed, new opportunities emerged to ensure the com- pany continues to thrive. Investment, innovation and job creation have been crucial in the mobilisation of the region’s biotech, pharmaceutical and medical fields. Our focus article on page 14 outlines their pursuit of urgent research and development projects, from diagnosis and vaccine research to personal protec- tion equipment and data science. Experts from a variety of fields are united in meeting the challenge. Underpinned by financial and technical support from public authori- ties, local companies are joining the international fight to Editor Sarah Crew better understand and address the global pandemic. We Deputy editor Sally Tipper look forward to following their ground-breaking journey Reporters Andy Furniere, Tomáš Miklica, Saffina Rana, Sarah Schug towards safeguarding public health. Art director Liesbet Jacobs Managing director Hans De Loore Don’t forget to download the WAB AWEX/WBI and Ackroyd Publications magazine app, available for Android Pascale Delcomminette – AWEX/WBI and iOS. -

La Bataille De Ligny

La Bataille de Ligny Règlements Exclusif Pour le Règlement de l’An XXX et Le Règlement des Marie-Louise 2 La Bataille de Ligny Copyright © 2013 Clash of Arms. December 30, 2013 • Général de brigade Colbert – 1re Brigade/5e Division de Cavalerie Légère All rules herein take precedence over any rules in the series rules, • Général de brigade Merlin – 2e Brigade/5e Division de which they may contradict. Cavalerie Légère • Général de brigade Vallin – 1re Brigade/6e Division de 1 Rules marked with an eagle or are shaded with a gray Cavalerie background apply only to players using the Règlements de • Général de brigade Berruyer – 2e Brigade/6e Division de l’An XXX. Cavalerie 3.1.3 Prussian Counter Additions NOTE: All references to Artillery Ammunition Wagons (AAWs,) 3.1.3.1 The 8. Uhlanen Regiment of the Prussian III Armeekorps was ammunition, ricochet fire, howitzers, grand charges and cavalry neither equipped with nor trained to use the lance prior to the advent skirmishers apply only to players using the Règlements de l’An XXX. of hostilities in June 1815. Therefore, remove this unit’s lance bonus and replace it with a skirmish value of (4). 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3.1.3.2 Leaders: Add the following leaders: • General der Infanterie Prinz Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich La Bataille de Ligny is a simulation of one of the opening battles of August von Preussen – Armee Generalstab the Waterloo campaign of 1815 fought between the Emperor • Oberstleutnant von Sohr – II. Armee-Corps, 2. Kavallerie- Napoléon and the bulk of the French L’Armée du Nord and Field Brigade Marshal Blücher, commander of the Prussian Army of the Lower • Oberst von der Schulenburg – II. -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

Failure in 1813: the Decline of French Light Infantry and Its Effect on Napoleon’S German Campaign

United States Military Academy USMA Digital Commons Cadet Senior Theses in History Department of History Spring 4-14-2018 Failure in 1813: The eclineD of French Light Infantry and its effect on Napoleon's German Campaign Gustave Doll United States Military Academy, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/history_cadet_etd Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Doll, Gustave, "Failure in 1813: The eD cline of French Light Infantry and its effect on Napoleon's German Campaign" (2018). Cadet Senior Theses in History. 1. https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/history_cadet_etd/1 This Bachelor's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at USMA Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cadet Senior Theses in History by an authorized administrator of USMA Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. United States Military Academy USMA Digital Commons Cadet Senior Theses in History Department of History Spring 4-14-2018 Failure in 1813: The eclineD of French Light Infantry and its effect on Napoleon's German Campaign Gustave Doll Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usmalibrary.org/history_cadet_etd UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY FAILURE IN 1813: THE DECLINE OF FRENCH LIGHT INFANTRY AND ITS EFFECT ON NAPOLEON’S GERMAN CAMPAIGN HI499: SENIOR THESIS SECTION S26 CPT VILLANUEVA BY CADET GUSTAVE A DOLL, ’18 CO F3 WEST POINT, NEW YORK 19 APRIL 2018 ___ MY DOCUMENTATION IDENTIFIES ALL SOURCES USED AND ASSISTANCE RECEIVED IN COMPLETING THIS ASSIGNMENT. ___ NO SOURCES WERE USED OR ASSISTANCE RECEIVED IN COMPLETING THIS ASSIGNMENT. -

Polish Battles and Campaigns in 13Th–19Th Centuries

POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 POLISH BATTLES AND CAMPAIGNS IN 13TH–19TH CENTURIES WOJSKOWE CENTRUM EDUKACJI OBYWATELSKIEJ IM. PŁK. DYPL. MARIANA PORWITA 2016 Scientific editors: Ph. D. Grzegorz Jasiński, Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Reviewers: Ph. D. hab. Marek Dutkiewicz, Ph. D. hab. Halina Łach Scientific Council: Prof. Piotr Matusak – chairman Prof. Tadeusz Panecki – vice-chairman Prof. Adam Dobroński Ph. D. Janusz Gmitruk Prof. Danuta Kisielewicz Prof. Antoni Komorowski Col. Prof. Dariusz S. Kozerawski Prof. Mirosław Nagielski Prof. Zbigniew Pilarczyk Ph. D. hab. Dariusz Radziwiłłowicz Prof. Waldemar Rezmer Ph. D. hab. Aleksandra Skrabacz Prof. Wojciech Włodarkiewicz Prof. Lech Wyszczelski Sketch maps: Jan Rutkowski Design and layout: Janusz Świnarski Front cover: Battle against Theutonic Knights, XVI century drawing from Marcin Bielski’s Kronika Polski Translation: Summalinguæ © Copyright by Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita, 2016 © Copyright by Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości, 2016 ISBN 978-83-65409-12-6 Publisher: Wojskowe Centrum Edukacji Obywatelskiej im. płk. dypl. Mariana Porwita Stowarzyszenie Historyków Wojskowości Contents 7 Introduction Karol Olejnik 9 The Mongol Invasion of Poland in 1241 and the battle of Legnica Karol Olejnik 17 ‘The Great War’ of 1409–1410 and the Battle of Grunwald Zbigniew Grabowski 29 The Battle of Ukmergė, the 1st of September 1435 Marek Plewczyński 41 The -

Prussian Forces, Battle of Ligny, 16 June 1815

Prussian Forces Battle of Ligny l6 June l8l5 Commanding Officer: Feldmarschal Blucher I Corps: Generallieutenant von Ziethen (Main body posted before St. Amand & Ligny. The advanced troops were posted between Lambusart & Heppignies) lst Brigade: Generalmajor von Steinmetz l2th Infantry Regiment (3) 24th Infantry Regiment (3) lst Westphalian Landwehr (3) (& jagers) 3/Silesian Schutzen Company 4/Silesian Schutzen Company 4th (lst Silesian) Hussars (4)(& jagers) 6pdr Foot Battery No. 7 6pdr Horse Battery No. 7 2nd Brigade: Generalmajor von Pirch II 6th Infantry Regiment (3) (& jagers) 28th Infantry Regiment (3) (& jagers) 2nd Westphalian Landwehr (3) (& jagers) lst Westphalian Landwehr Cavalry (4)(& Jagers) 6pdr Foot Battery No. 3 3rd Brigade: Generalmajor von Jagow 7th Infantry Regiment (3)(& jagers) 29th Infantry Regiment (3)(& jagers) 3rd Westphalian Landwehr (3)(& jagers) l/Silesian Schutzen 2/Silesian Schutzen 6pdr Foot Battery No. 8 4th Brigade: Generalmajor von Henckel l3th Infantry Regiment (3) l9th Infantry Regiment (3) 4th Westphalian Landwehr (3)(& jagers) 6pdr Foot Battery No. l5 Corps Cavalry: Generalmajor von Roder lst Brigade: Generalmajor von Treckow 5th (Brandenburg) Dragoon Regiment (4) 2nd (lst West Prussian) Dragoon Regiment(4) 3rd (Brandenburg) Uhlan Regiment (4) 6pdr Horse Battery No. 7 2nd Brigade: Oberstlieutenant von Lutzow 6th (2nd West Prussian) Uhlan Regiment (4) lst Kurmark Landwehr Cavalry (4) 2nd Kurmark Landwehr Cavalry (4) Artillery: Generalmajor von Holzendorff l2pdr Foot Battery No. 2 l2pdr Foot Battery No. 6 l2pdr Foot Battery No. 9 6pdr Foot Battery No. l 6pdr Horse Battery No. l0 Howitzer Battery No. l lst Field Pioneer Company 2nd Field Pioneer Company 1 II Corps: Generallieutenant von Pirch I (Corps posted by Sombreuf & Mazy) 5th Brigade: Generalmajor von Tippelskirch 2nd Infantry Regiment (3) (& jagers) 25th Infantry Regiment (3)(& jagers) 5th Westphalian Landwehr (3)(& jagers) Field Jager Company 6pdr Foot Battery No. -

Wellington's Two-Front War: the Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Wellington's Two-Front War: The Peninsular Campaigns, 1808-1814 Joshua L. Moon Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WELLINGTON’S TWO-FRONT WAR: THE PENINSULAR CAMPAIGNS, 1808 - 1814 By JOSHUA L. MOON A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History In partial fulfillment of the Requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Joshua L. Moon defended on 7 April 2005. __________________________________ Donald D. Horward Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________ Patrick O’Sullivan Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Jonathan Grant Committee Member ______________________________ Edward Wynot Committee Member ______________________________ Joe M. Richardson Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named Committee members ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS No one can write a dissertation alone and I would like to thank a great many people who have made this possible. Foremost, I would like to acknowledge Dr. Donald D. Horward. Not only has he tirelessly directed my studies, but also throughout this process he has inculcated a love for Napoleonic History in me that will last a lifetime. A consummate scholar and teacher, his presence dominates the field. I am immensely proud to have his name on this work and I owe an immeasurable amount of gratitude to him and the Institute of Napoleon and French Revolution at Florida State University.