Fragmenta Hellenoslavica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith Bithos, George P. How to cite: Bithos, George P. (2001) Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4239/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 METHODIOS I PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE Churchman, Politician and Confessor for the Faith Submitted by George P. Bithos BS DDS University of Durham Department of Theology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Orthodox Theology and Byzantine History 2001 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including' Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately. -

On the Greek Original Manuscript and the Old Bulgarian Translation of a Vita Incorporated in the Codex Suprasliensis

https://doi.org/10.26262/fh.v4i0.6315 Dr. Nevena Gavazova Associate Professor University “St. St. Cyril and Methodius” of Veliko Tarnovo On the Greek Original Manuscript and the Old Bulgarian Translation of a Vita Incorporated in The Codex Suprasliensis. Preliminary Observations. The object of this research is The Vita of The Holy 42 Martyrs of Amorium known by only one South Slavic transcript1 in The Codex Suprasliensis2. There it is placed with the following incipit, dated 7th March: 1 Until now, I’m aware of only one late Russian transcript in XVIth century Codex, collection of the Meletski Monastery /folio 303/, № 117п – it is in Kiev, “V.I. Vernadskiy” National Library of Ukraine, folios 172a – 181б: Мц(сђ)а марта sђ. дЃнь м(])н¶е сЃт¥(х) ё славн¥(х) с м]Ѓнкь. »еw(д)ра константёна. »еwфёла. калёста васоÿ. ё дрYжён¥ ёхь. мЃв ё(ж) въ амореё. Beginning: На мЃ]нё]ьск¥ стр(сђ)тё ре(]ђ). любщ∙ёмь мЃ]нк¥ да прострем с. блг(д)тё въземлще wUU нё(х). новоÿвльшём с на(м) ]лЃко(м). ёдýте убо станýте дне(сђ) да смотрё(м) добраго съвъкуплен∙а. The description of the manuscript is according to the Annex in: Rediscovering: The Codex Suprasliensis – Xth century Old Bulgarian Literary Monument. BAS, Sofia, 2012, 447,450. 2 Hereinafter referred to as Supr. In the Codex, the Vita is the fourth one, placed on folios 27b to 34b, dated 7th March, anonymous. In the present study the text is given according to the critical edition Заимов, Й., М. Капалдо. -

Byzantium and Islam” 2003-2017 Rivista Online Registrata, Codice ISSN 2240-5240 Porphyra N

Anno XIII Numero XXV Dicembre 2016 “Byzantium and Islam” 2003-2017 Rivista online registrata, codice ISSN 2240-5240 Porphyra n. 25, anno XIII, ISSN 2240-5240 ______________________________________________________________________ In memory of Alessandro Angelucci 2 Porphyra n. 25, anno XIII, ISSN 2240-5240 ______________________________________________________________________ Indice articoli: 1. L’AMBASCERIA DI COSTANTE II IN CINA (641-643): UN INEDITO TENTATIVO DI ALLEANZA ANTI-ARABA? Mirko Rizzotto pp. 5-25 2. FILELLENISMO E ANTIBIZANTINISMO. LA POLITICA CULTURALE DEI PRIMI CALIFFI ABBASIDI Filippo Donvito pp. 26-42 3. PHOTIUS AND THE ABBASIDS: THE PROBLEMS OF ISLAMO-CHRISTIAN PARADIGMS Olof Heilo pp. 43-51 4. TEOFILO, NAṢR E I KHURRAMIYYA IRREDENTISMI POLITICO- MESSIANICI NEL IX SECOLO, TRA IRAN, ISLAM E BISANZIO. Andrea Piras pp. 52-67 5. THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN THE CALIPHATE AND BYZANTIUM FOR THE CITY OF AMORİUM (AMORION) Talat Koçak pp. 68-85 6. BISANZIO E GLI ARABI NEL CONTESTO DELLA VITA SANCTI MICHAELIS SYNCELLI (BHG 1296) Elena Gritti pp. 86-100 7. BISANZIO E L’ISLAM (1025-1081) Frederick Lauritzen pp. 101-112 8. DID THE CRUSADES CHANGE THE BYZANTINE PERCEPTION OF VIOLENCE? David-John Williams pp. 113-124 9. PER LO STUDIO DELLA INFLUENZA TURCA NELL’IMPERO DEI ROMANI: IL CASO DEL SIMBOLO DELL’AQUILA BICIPITE (SECC. XII-XIII) Giorgio Vespignani pp. 125-131 10. LA RISPOSTA DEL MONDO MERCANTILE ALL’AVANZATA DEI TURCHI Sandra Origone pp. 132-143 11. PETROS PELOPONNESIOS. ABOUT AUTHORSHIP IN OTTOMAN MUSIC AND THE HERITAGE OF BYZANTINE MUSIC Oliver Gerlach pp. 144-183 Indice recensioni: 12. Φ.A. ΔΗΜΗΤΡΑΚΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ, Ὁ ἀναµενόµενος: ἅγιος βασιλεὺς Ἰωάννης Βατάτζης ὁ ἐλεήµων. -

Saints Peter and Paul Byzantine Catholic Church

42 MARTYRS OF AMORIUM The Holy 42 Martyrs of Amorium (†845) — Passion-bearers Constantine, Aetius, Saints Peter & Paul Theophilus, Theodore, Melissenus, Callistus, Basoes and 35 others with them — were prominent officers and notables of the Byzantine city of Amorium, one of Byzantium's Byzantine largest and most important cities at the time, who were seized following the capture and systematic destruction of the city in 838 AD by the Abbasid caliph Al-Mu'tasim, then taken as hostages to Samarra (today in Iraq) and executed there seven years later for Catholic Church refusing to convert to Islam. Their feast day is celebrated on March 6. Amorium was an episcopal see (bishopric) as early as 431, and was fortified by the Emperor Zeno, but did not rise to prominence until the 7th century. Its strategic location 431 GEORGE STREET * BRADDOCK, PENNSYLVANIA 15104 * TELEPHONE (412) 461-1712 in central Asia Minor made the city a vital stronghold against the armies of the Arab Webpage: https://stspeterpaulbcc.com/ Caliphate following their conquest of the Levant. E-male: [email protected] The city was first attacked by the Arabs in 644, and taken in 646. Over the next two centuries, it remained a frequent target of Muslim raids (razzias) into Asia Minor, ADMINISTRATOR: FATHER VITALII STASHKEVYCH especially during the great sieges of 716 and 796. It became the capital of the theme of Anatolikon soon after. PARISH OFFICE: 4200 HOMESTEAD DUQUESNE RD, In 742-743, it was the main base of iconoclast Emperor Constantine V against the usurper Artabasdos. In 820, MUNHALL, PA, 15120 an Amorian, Michael II, ascended the Byzantine throne, establishing the Amorian dynasty. -

Byzantine Names for SCA Personae

1 A Short (and rough) Guide to Byzantine Names for SCA personae This is a listing of names that may be useful for constructing Byzantine persona. Having said that, please note that the term „Byzantine‟ is one that was not used in the time of the Empire. They referred to themselves as Romans. Please also note that this is compiled by a non-historian and non-linguist. When errors are detected, please let me know so that I can correct them. Additional material is always welcomed. It is a work in progress and will be added to as I have time to research more books. This is the second major revision and the number of errors picked up is legion. If you have an earlier copy throw it away now. Some names of barbarians who became citizens are included. Names from „client states‟ such as Serbia and Bosnia, as well as adversaries, can be found in my other article called Names for other Eastern Cultures. In itself it is not sufficient documentation for heraldic submission, but it will give you ideas and tell you where to start looking. The use of (?) means that either I have nothing that gives me an idea, or that I am not sure of what I have. If there are alternatives given of „c‟, „x‟ and „k‟ modern scholarship prefers the „k‟. „K‟ is closer to the original in both spelling and pronunciation. Baron, OP, Strategos tous notious okeanous, known to the Latins as Hrolf Current update 12/08/2011 Family Names ............................................................. 2 Male First Names ....................................................... -

In Studies in Byzantine Sigillography, I, Ed. N. Oikonomides (Washington, D.C., 1987), Pp

Notes I. SOURCES FOR EARLY MEDIEVAL BYZANTIUM 1. N. Oikonomides, 'The Lead Blanks Used for Byzantine Seals', in Studies in Byzantine Sigillography, I, ed. N. Oikonomides (Washington, D.C., 1987), pp. 97-103. 2. John Lydus, De Magistratibus, in Joannes Lydus on Powers, ed. A. C. Bandy (Philadelphia, Penn., 1983), pp. 160-3. 3. Ninth-century deed of sale (897): Actes de Lavra, 1, ed. P. Lemerle, A. Guillou and N. Svoronos (Archives de l'Athos v, Paris, 1970), pp. 85-91. 4. For example, G. Duby, La societe aux xi' et xii' sii!cles dans la region maconnaise, 2nd edn (Paris, 1971); P. Toubert, Les structures du Latium medieval, 2 vols (Rome, 1973). 5. DAI, cc. 9, 46, 52, pp. 56-63, 214-23, 256-7. 6. De Cer., pp. 651-60, 664-78, 696-9. 7. See S. D. Goitein, A Mediterranean Society, 5 vols (Berkeley, Cal., 1967- 88), I, pp. 1-28. , 8. ]. Darrouzes, Epistoliers byzantins du x' sii!cle (Archives de I' orient Chretien VI, Paris, 1960), pp. 217-48. 9. Photius, Epistulae et Amphilochia, ed. B. Laourdas and L. G. Westerink, 6 vols (Leipzig, 1983-8), pope: nrs 288, 290; III, pp. 114-20, 123-38, qaghan of Bulgaria: nrs 1, 271, 287; 1, pp. 1-39; II, pp. 220-1; III, p. 113-14; prince of princes of Armenia: nrs 284, 298; III, pp. 1-97, 167-74; katholikos of Armenia: nr. 285; III, pp. 97-112; eastern patriarchs: nrs 2, 289; 1, pp. 39-53; III, pp. 120-3; Nicholas I, patriarch of Constantinople, Letters, ed. -

BİZANS Yeni Roma Imparatorluğu

BİZANS Yeni Roma imparatorluğu CyrilM ango Oxford üniversitesi'nde Bizans ve Modem Grek Dili profe sörüdür. Exeter·College öğretim üyesi ve Bizans sanatı, arkeolojisi, tarihi ve edebiyatı üzerine birçok kitap ve makalenin yazandır. Gül Çağalı Güven Ankara Üniversitesi tletişim FakÜltesi'ni bitirdi (1982); Boğaziçi üniversitesi'nde tarih yüksek lisansı yaptı. Çeşitli dergi ve gazetelerde muhabir. Cumhuriyet'te Çeviri Servisi şefi (1993-94), Ak soy Yayıncılık'ta editör (1997-98) olarak çalıştı. Tarih, edebiyat, felsefe ve medya/iletişim gibi değişik alanlarda çeviriler yaptı. CYRIL MANGO , Bizans Yeni Roma imparatorluğu Çeviren: Gül Güven Çağalı /fıA..ArN. omo İSTANBUL Yapı Kredi Yayınları -2720 Tarih - 42 BiZANS Yeni Roma imparatorluğu I Cyril Mango Özgün adı: Byzantium-The Empire ofThe New Rome Çeviren: Gül Çağalı Güven Kitap editörü: Nuri Akbayar Düzelti: Hakan Toker Kapak tasarımı: Nahide Dikel Grafik uygulama: Gülçin Erol Baskı: üç-Er Ofset Yüzyıl Malı. Massit 3. Cad. No: 195 Bağcıları lstanbul ı. baskı: lstanbul, Haziran 2008 ISBN 978- 975-08-1410-5 ©Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık Ticaret ve Sanayi A.Ş . .2007 Sertifika No: 1206-34-003513 · Copyright © 1980 by Cyril Mango Bütün yayın hakları saklıdır. Kaynak gösterilerek tanıtım için yapılacak kısa alıntılar dışında yayıncının yazılı izni olmaksızın hiçbir yolla çoğaltılamaz. Yapı Kredi Kültür Sanat Yayıncılık Ticaret ve Sanayi A.Ş. Yapı Kredi Kültür Merkezi istiklal Caddesi No. 161 Beyoğlu 34433 lstanbul Telefon: (O 212) 252 47 00 (pbx) Faks: (O 212) 293 07 23 http://www.yapikrediyayinlari.com -

Conversion and Religious Identity in Early Islamic

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO BY THE BOOK: CONVERSION AND RELIGIOUS IDENTITY IN EARLY ISLAMIC BILĀD AL-SHĀM AND AL-JAZĪRA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY JESSICA SYLVAN MUTTER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2018 Table of Contents Chapter 1: A Review of Relevant Literature on Religious Conversion: Toward a Theory of Conversion in Early Islam………………………………………………………………………...1 Conversion and Conversion Studies: A Christian Phenomenon?.………………………...1 Conversion in the Formative Era of Religions…………………………………………....7 The Limits of Terminology………………………………………………………………15 Terminology of Conversion in the Qur’an……………………………………………….20 Ontological Conversions…………………………………………………………………22 Creative Methodologies for Studying Conversion………………………………………24 Studies of Conversion and Related Phenomena in Early and Medieval Islam..................32 Chapter 2: Historical Representations of Conversion in Early Islamic Syria and the Jazira…….41 Historical Documentation of Conversion and Related Phenomena, 640-770 CE……….45 Thomas the Presbyter.........................................................................................................49 The Maronite Chronicle.....................................................................................................49 Isho ‘Yahb III.....................................................................................................................52 Sebeos................................................................................................................................55 -

A History of Byzantium

A History of Byzantium AHOA01 1 24/11/04, 5:49 PM Blackwell History of the Ancient World This series provides a new narrative history of the ancient world, from the beginnings of civilization in the ancient Near East and Egypt to the fall of Constantinople. Written by experts in their fields, the books in the series offer authoritative accessible surveys for students and general readers alike. Published A History of Byzantium Timothy E. Gregory A History of the Ancient Near East Marc Van De Mieroop In Preparation A History of Ancient Egypt David O’Connor A History of the Persian Empire Christopher Tuplin A History of the Archaic Greek World Jonathan Hall A History of the Classical Greek World P. J. Rhodes A History of the Hellenistic World Malcolm Errington A History of the Roman Republic John Rich A History of the Roman Empire Michael Peachin A History of the Later Roman Empire, AD 284–622 Stephen Mitchell AHOA01 2 24/11/04, 5:49 PM A History of Byzantium Timothy E. Gregory AHOA01 3 24/11/04, 5:49 PM © 2005 by Timothy E. Gregory BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Timothy E. Gregory to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

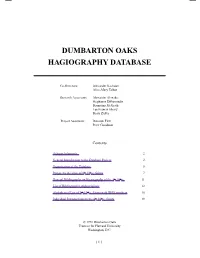

Dumbarton Oaks Hagiography Database

DUMBARTON OAKS HAGIOGRAPHY DATABASE Co-Directors: Alexander Kazhdan Alice-Mary Talbot Research Associates: Alexander Alexakis Stephanos Efthymiadis Stamatina McGrath Lee Francis Sherry Beate Zielke Project Assistants: Deborah Fitzl Peter Goodman Contents Acknowledgments 2 General Introduction to the Database Project 2 Organization of the Database 5 Preface to the vitae of 8th-10th c. Saints 7 General Bibliography on Hagiography of the 8th-10th c. 11 List of Bibliographic Abbreviations 12 Alphabetical List of 8th-10th c. Saints with BHG numbers 16 Individual Introductions to the 8th-10th c. Saints 19 © 1998 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. [ 1 ] ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The staff and directors of the Hagiography Database Project would like to express their appreciation to Dumbarton Oaks which supported the project from 1991-1998, and to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation which made a generous grant to the project for the years 1994-1997 to supplement Dumbarton Oaks funding. We also thank Owen Dall, president of Chesapeake Comput- ing Inc., for his generous forbearance in allowing Buddy Shea, Stacy Simley, and Kathy Coxe to spend extra time at Dumbarton Oaks in the development of the Hagiography database. Special mention must be made of the effort Buddy Shea put into this project with his congenial manner and strong expertise. Without Buddy the project as we now know it would not exist. GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE DATABASE PROJECT Hagiography was one of the most important genres of Byzantine literature, both in terms of quantity of written material and the wide audience that read or listened to these texts. The Dumbarton Oaks Hagiography Database Project is designed to provide Byzantinists and other medievalists with new opportunities of access to this important and underutilized corpus of Greek texts. -

Digenes Akrites

DIGENES AKRITES EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY BY JOHN MAVROGORDATO FORMERLY BYWATER AND SOTHEBY PROFESSOR OF BYZANTINE AND MODERN GREEK LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD AND FELLOW OF EXETER COLLEGE OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS Oxford University Press, Ely House, London W.I GLASGOW NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE WELLINGTON CAPE TOWN SALISBURY IBADAN NAIROBI LUSAKA ADDIS ABABA BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI LAHORE DACCA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE HONG KONG TOKYO FIRST PUBLISHED 1956 REPRINTED LITHOGRAPHICALLY AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, OXFORD FROM SHEETS OF THE FIRST EDITION 1963, 1970 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN PREFACE MANY years ago my friend Petros Petrides, himself born at Nigde in Kappadokia, used to tell me about the stories of Digenes, which were to inspire his own dramatic symphony first performed in Athens in May 1940. When at last I started to read for myself this heroic poem of Twyborn the Borderer, who guarded the marches of the Byzantine Empire in the tenth or eleventh century, I was alone in the country, and found my way through the text as best I could; if some of the notes now published sound like an ingenuous soliloquy, it is from that early period they must have survived— excusata suo tempore, lector, habe; exsul eram. Later on I was back in London, and there enjoyed the advice and encouragement of Nor- man Baynes, of F. H. Marshall, and of Romilly Jenkins; somehow or other my translation and a few lectures were on paper in 1938; and not long afterwards, thanks perhaps largely to their continued interest, I found myself living in College at Oxford and on the same staircase as my friend R. -

A Comparative Study of External Architectural Display on Middle Byzantine Structures on the Black Sea Littoral

THE OUTSIDE IMAGE: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF EXTERNAL ARCHITECTURAL DISPLAY ON MIDDLE BYZANTINE STRUCTURES ON THE BLACK SEA LITTORAL by ROGER STEPHEN SHARP A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT. This study is concerned with the manner in which Byzantium manifested itself through the exterior of its buildings. The focus is the Black Sea from the ninth century to the eleventh. Three cities are examined. Each had imperial attention: Amastris for imperial defences; Mesembria, a border city and the meeting place for diplomats: Cherson, a strategic outpost and focal point of Byzantine proselytising. There were two forms of external display; one, surface ornament and surface modelling, the other through the arrangement of masses and forms. A more nuanced division can be discerned linked with issues of purpose and audience. The impulse to display the exterior can be traced to building practice at imperial level in the capital in the early ninth century.