Paul Coldwell • Genji's World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Rembrandt Packet Aruni and Morgan.Indd

Rembrandt Harmenszoon Van Rijn Etchings Education Packet The Florida State University September 20- October 6 Museum of Fine Arts See website for updates of times, www.MOFA.fsu.edu hours and events. Table of Contents Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn Biography ...................................................................................................................................................2 Rembrandt’s Styles and Influences ............................................................................................................ 3 Printmaking Process ................................................................................................................................4-5 Focus on Individual Prints: Landscape with Three Trees ...................................................................................................................6-7 Hundred Guilder .....................................................................................................................................8-9 Beggar’s Family at the Door ................................................................................................................10-11 Suggested Art Activities Three Trees: Landscape Drawings .......................................................................................................12-13 Beggar’s Family at the Door: Canned Food Drive ................................................................................14-15 Hundred Guilder: Money Talks ..............................................................................................16-18 -

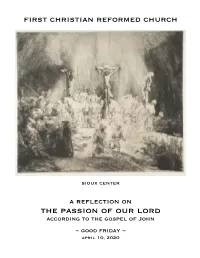

2020 Good Friday Order of Service

first christian reformed church sioux center a reflection on the passion of our lord according to the gospel of John ~ good friday ~ april 10, 2020 order of service Prelude ~ “Were you There” Linker “O Sacred Head” Burkhardt Welcome Call to Worship Today we remember Jesus was crucified. He was pierced for our transgressions. He suffered and died for our iniquities. We remember the sacrifice of our Lord with gratitude because his death gives us life and brings redemption to the world. Let us worship our Savior. Prayer of Invocation O God, who for our redemption gave your only Son to the death of the cross, and by his glorious resurrection delivered us from the power of our enemy: grant us so to die daily to sin, that we may evermore live with him in the joy of his resurrection, now and forever. Prayers of Intercession and Illumination Hymn: “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence,” verses 1-3 Hymn continued on the next page. Scripture Reading: John 18.1-14 ~ Jesus’ Arrest and Betrayal Hymn: “Meekness and Majesty” ~ Lif Up Your Hearts 157, verses 1-3 Verse 1: Verse 2: Meekness and majesty, manhood and Deity Father's pure radiance, perfect in innocence, in perfect harmony, the Man who is God. yet learns obedience to death on a cross, Lord of eternity dwells in humanity, suffering to give us life, conquering through sacrifice, kneels in humility, and washes our feet. and, as they crucify, prays, “Father forgive.” Chorus: Chorus Oh, what a mystery—meekness and majesty; bow down and worship, for this is your God. -

The Making of Paula Rego's 'The Nursery Rhymes'

The making of Paula Rego’s ‘The Nursery Rhymes’ Abstract This article looks at the series of etchings and aquatints entitled The Nursery Rhymes that Paula Rego made in 1989 in collaboration with printer Professor Paul Coldwell. Whilst she had already had some printmaking experience, The Nursery Rhymes constituted her first major engagement with printmaking. The article considers the circumstances under which the prints were made, both in terms of her personal circumstances and her professional standing, and examines their reception and continuing popularity. It also gives personal insights and commentary on the series, looking at both her iconography and her connection to a wide range of graphic work. It does so from the author’s unique perspective as the printer and collaborator in the project and offers insights into the working relationship between artist and printer. The making of Paula Rego’s ‘The Nursery Rhymes’ Paul Coldwell Paula Rego has always identified with the least, not the mighty, taken the child’s eye view, and counted herself among the commonplace and the disregarded, by the side of the beast, not the beauty… Her sympathy with naiveté, her love of its double character, its weakness and its force, has led her to Nursery Rhymes as a new source for her imagery. (Warner 1989) Paula Rego was born in Lisbon in 1935 and attended the Slade School of Art in London between 1952–56 where she met her husband, the painter Victor Willing. In 1957 she returned to live in Portugal with her three children, living between London and Portugal for a few years before finally settling in London in 1976. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

The Exploration of Light As a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 8-7-1972 The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium Mary Vasko Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Vasko, Mary, "The Exploration of Light as a Means of Expression in the Intaglio Print Medium" (1972). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EXPLORATION OF LIGHT AS A MEANS OF EXPRESSION IN THE INTAGLIO PRINT MED I UH by Sister Mary Lucia Vasko, O.S.U. Candidate for the Master of Fine Arts in the College of Fine and Applied Arts of the Rochester Institute of Technology Submitted: August 7, 1372 Chief Advisor: Mr. Lawrence Williams TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . i i i INTRODUCTION v Thesis Proposal V Introduction to Research vi PART I THESIS RESEARCH Chapter 1. HISTORICAL BEGINNINGS AND BACKGROUND OF LIGHT AS AN ARTISTIC ELEMENT THE USE OF CHIAROSCURO BY EARLY ITALIAN AND GERMAN PRINTMAKERS INFLUENCE OF CARAVAGGIO ON DRAMATIC LIGHTING TECHNIQUE 12 REMBRANDT: MASTER OF LIGHT AND SHADOW 15 Light and Shadow in Landscape , 17 Psychological Illumination of Portraiture . , The Inner Light of Spirituality in Rembrandt's Works , 20 Light: Expressed Through Intaglio . Ik GOYA 27 DAUMIER . 35 0R0ZC0 33 PICASSO kl SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION OF RESEARCH hi PART I I THESIS PROJECT Chapter Page 1. -

Stowe: a Description of the Magnificent House and Gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Grenville Nugent Temple

www.e-rara.ch Stowe: a description of the magnificent house and gardens of the Right Honourable Richard Grenville Nugent Temple ... Seeley, Robert Benton Buckingham, 1780 ETH-Bibliothek Zürich Shelf Mark: Rar 6719 Persistent Link: http://dx.doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-830 A Description of the House. www.e-rara.ch Die Plattform e-rara.ch macht die in Schweizer Bibliotheken vorhandenen Drucke online verfügbar. Das Spektrum reicht von Büchern über Karten bis zu illustrierten Materialien – von den Anfängen des Buchdrucks bis ins 20. Jahrhundert. e-rara.ch provides online access to rare books available in Swiss libraries. The holdings extend from books and maps to illustrated material – from the beginnings of printing to the 20th century. e-rara.ch met en ligne des reproductions numériques d’imprimés conservés dans les bibliothèques de Suisse. L’éventail va des livres aux documents iconographiques en passant par les cartes – des débuts de l’imprimerie jusqu’au 20e siècle. e-rara.ch mette a disposizione in rete le edizioni antiche conservate nelle biblioteche svizzere. La collezione comprende libri, carte geografiche e materiale illustrato che risalgono agli inizi della tipografia fino ad arrivare al XX secolo. Nutzungsbedingungen Dieses Digitalisat kann kostenfrei heruntergeladen werden. Die Lizenzierungsart und die Nutzungsbedingungen sind individuell zu jedem Dokument in den Titelinformationen angegeben. Für weitere Informationen siehe auch [Link] Terms of Use This digital copy can be downloaded free of charge. The type of licensing and the terms of use are indicated in the title information for each document individually. For further information please refer to the terms of use on [Link] Conditions d'utilisation Ce document numérique peut être téléchargé gratuitement. -

Setting Memory – Bettina Von Zwehl & Paul Coldwell Special Exhibition at the Sigmund Freud Museum, 7/10/2016 – 21/1/2017 Opening: 6 October 2016, 7Pm

Setting Memory – Bettina von Zwehl & Paul Coldwell Special exhibition at the Sigmund Freud Museum, 7/10/2016 – 21/1/2017 Opening: 6 October 2016, 7pm Works by London-based artists Bettina von Zwehl and Paul Coldwell kick off the discourse about “loss, memory and reorientation” at the Sigmund Freud Museum on 7 October, 2016 – notions that today define the atmosphere of the former living and working rooms of Sigmund and Anna Freud. The exhibition SETTING MEMORY at Vienna’s Berggasse corresponds with personal shows by the artists at the Freud Museum in London and thus underlines the close relationship of these two Freud institutions. Bettina von Zwehl uses the quality of photography as a tool of memory and instrument of research, following the main principles of psychoanalytic treatment methods: criteria such as “observation”, “transference” and the “principle of confidentiality” are subjected to artistic scrutiny in a series of portraits. Photographs from a series documenting Anna Freud’s personal belongings in London afford insights into past life-worlds – visual reminiscences returned to their place of origin that depict the setting of the early history of pedagogy and child analysis in “Red Vienna” of the 1920s. The multi-part installation Sospiri (Sighs) stages experiences of loss and mourning: inspired by Gerhard Richter’s work, the artist combines personal traces of life and memory in an unembellished photographic memory record. Paul Coldwell picks up from those historical events that left the house at Berggasse 19 a “vestigial memory space”. By reconstructing antiques that once populated Freud’s desk, Coldwell revives the memory of the ambience of Sigmund Freud’s workplace. -

![Francis Grose, Ed.] Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3221/francis-grose-ed-classical-dictionary-of-the-vulgar-tongue-853221.webp)

Francis Grose, Ed.] Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue

A landmark in the lexicography of slang in its first edition [Francis Grose, ed.] Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. London: S.[Samuel] Hooper, 1785. 8vo, [208] pages. Francis Grose (ca. 1730–1791) was the son of the Swiss jeweler who created the coronation crown of George II. With assistance from his father, Grose (who developed a precocious interest in antiquities) was appointed to be Richmond Herald in the College of Arms, a post he held from 1755 to 1763. After attaining the rank of captain in the military, Grose set out to research and produce drawings for his first book, The Antiquities of England and Wales (1773–87), which was commercially successful. Grose’s next work, A Guide to Health, Beauty, Riches, and Honour (1783) contained a collection of contemporary quack advertisements with a satirical preface. In the compilation of his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, Grose, accompanied by his amanuensis and fellow artist Tom Cocking, collected slang terms during late-night visits to London’s roughest neighborhoods and drinking establishments. Grose went on to author A Provincial Glossary (1787) “with a collection of local proverbs and popular superstitions,” Rules for Drawing Caricatures (1788), The Antiquities of Scotland (1789–91), and A Treatise on Ancient Armour and Weapons (1791). While traveling in Scotland making preparations for The Antiquities of Scotland, Grose made the acquaintance of poet Robert Burns and was subsequently immortalized in Burns’ “Verses on Captain Grose” and “On the late Captain Grose’s Peregrinations.” Francis Grose was a corpulent and convivial person who took great pleasure in food and drink; it is fitting that in 1791, soon after traveling to Dublin to start a book on Irish antiquities, he died at the dinner table (reputedly by choking). -

Antiquarian Prints1

Antiquarian Topographical Prints 1550-1850 (As they relate to castle studies) Bibliography Antiquarianism - General Peter N. Miller, (2017). History and Its Objects: antiquarianism and material culture since 1500. NY: Cornell Univ Press. David Gaimster, Bernard Nurse, Julia Steele (eds.), (2007), Making History: Antiquaries in Britain 1707-2007 (London, the Royal Academy of Arts & the Society of Antiquaries, Exhibition Catalogue).* Susan Pearce, (ed) (2007). Visions of Antiquity: The Society of Antiquaries of London 1707–2007. (Society of Antiquaries).* Jan Broadway (2006). "No Historie So Meete": gentry culture and the development of local history in Elizabethan and early Stuart England. Manchester: Manchester University Press. R. Sweet, (2004). Antiquaries: the discovery of the past in eighteenth-century Britain. (London: Hambledon Continuum). Daniel Woolf (2003). The Social Circulation of the Past: English historical culture 1500–1730. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Anthony Griffiths, (1998) The Print in Stuart Britain: 1603-1689,[Exhibition Cat.] British Museum Press.* Philippa Levine, (1986). The Amateur and the Professional: antiquarians, historians and archaeologists in Victorian England, 1838–1886. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press). J. Evans, (1956), A history of the Society of Antiquaries, (Oxford University Press for the Society of Antiquaries) D. J. H Clifford (2003), The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford (The History Press Ltd). Topographical Prints and Painting - General Ronald Russell, (2001), Discovering Antique Prints (Shire Books)* Julius Bryant, (1996), Painting the Nation - English Heritage properties as seen by Turner, (English Heritage, London)* Peter Humphries, (1995), On the Trail of Turner in North and South Wales, (Cadw, Cardiff). Andrew Wilton & Anne Lyles (1993), The Great Age of British Watercolours, (Prestel - Exhibition catalogue)* Lindsay Stainton, (1991) Nature into Art: English Landscape Watercolours, (British Museum Press)* Especially Section II ‘Man in the Landscape’ pp. -

Rembrandt Remembers – 80 Years of Small Town Life

Rembrandt School Song Purple and white, we’re fighting for you, We’ll fight for all things that you can do, Basketball, baseball, any old game, We’ll stand beside you just the same, And when our colors go by We’ll shout for you, Rembrandt High And we'll stand and cheer and shout We’re loyal to Rembrandt High, Rah! Rah! Rah! School colors: Purple and White Nickname: Raiders and Raiderettes Rembrandt Remembers: 80 Years of Small-Town Life Compiled and Edited by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins Des Moines, Iowa and Harrisonburg, Virginia Copyright © 2002 by Helene Ducas Viall and Betty Foval Hoskins All rights reserved. iii Table of Contents I. Introduction . v Notes on Editing . vi Acknowledgements . vi II. Graduates 1920s: Clifford Green (p. 1), Hilda Hegna Odor (p. 2), Catherine Grigsby Kestel (p. 4), Genevieve Rystad Boese (p. 5), Waldo Pingel (p. 6) 1930s: Orva Kaasa Goodman (p. 8), Alvin Mosbo (p. 9), Marjorie Whitaker Pritchard (p. 11), Nancy Bork Lind (p. 12), Rosella Kidman Avansino (p. 13), Clayton Olson (p. 14), Agnes Rystad Enderson (p. 16), Alice Haroldson Halverson (p. 16), Evelyn Junkermeier Benna (p. 18), Edith Grodahl Bates (p. 24), Agnes Lerud Peteler (p. 26), Arlene Burwell Cannoy (p. 28 ), Catherine Pingel Sokol (p. 29), Loren Green (p. 30), Phyllis Johnson Gring (p. 34), Ken Hadenfeldt (p. 35), Lloyd Pressel (p. 38), Harry Edwall (p. 40), Lois Ann Johnson Mathison (p. 42), Marv Erichsen (p. 43), Ruth Hill Shankel (p. 45), Wes Wallace (p. 46) 1940s: Clement Kevane (p. 48), Delores Lady Risvold (p. -

Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 a Dissertation Submitted in Part

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Sentiment and Laughter: Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Leigh-Michil George 2016 © Copyright by Leigh-Michil George 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Sentiment and Laughter: Caricature in the Novel, 1740-1840 by Leigh-Michil George Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Jonathan Hamilton Grossman, Co-Chair Professor Felicity A. Nussbaum, Co-Chair This dissertation examines how late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century British novelists—major authors, Laurence Sterne and Jane Austen, and lesser-known writers, Pierce Egan, Charles Jenner, and Alexander Bicknell—challenged Henry Fielding’s mid-eighteenth-century critique of caricature as unrealistic and un-novelistic. In this study, I argue that Sterne, Austen, Egan, and others translated visual tropes of caricature into literary form in order to make their comic writings appear more “realistic.” In doing so, these authors not only bridged the character-caricature divide, but a visual- verbal divide as well. As I demonstrate, the desire to connect caricature with character, and the visual with the verbal, grew out of larger ethical and aesthetic concerns regarding the relationship between laughter, sensibility, and novelistic form. ii This study begins with Fielding’s Joseph Andrews (1742) and its antagonistic stance towards caricature and the laughter it evokes, a laughter that both Fielding and William Hogarth portray as detrimental to the knowledge of character and sensibility. My second chapter looks at how, increasingly, in the late eighteenth century tears and laughter were integrated into the sentimental experience.