A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

Feminist Periodicals

The Un vers ty of W scons n System Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents WOMEN'S STUDIES Volume 26, Number 4, Winter 2007 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard LIBRARIAN Women's Studies Librarian Feminist Periodicals A current listing of contents Volume 26, Number 4 (Winter 2007) Periodical literature is the cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing of Contents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminist Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table of contents pages from current issues ofmajorfeministjournalsare reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the follOWing information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of pUblication. 3. Subscription prices (print only; for online prices, consult publisher). 4. Subscription address. -

Troops Meet No Fight in Taking IRA Enelaves

Mancheater-— A City of Village Charm MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JULY 3X, 1972 Barriers Troops Meet No Fight Collapse By ED BL.ANGHE LONDONERRY, Northern Ireland (AP) — The first sol In Taking IRA Enelaves diers sllpx>ed silently into the Creggan district of Londonder ry, their blackened faces LONDONDERRY North- extent of what has happened kept up barrages of obscenities, down their roadblocks as soon streaked by rain. ern Ireland (A P )—__ British sunk in and they have had Outside a church, a crowd of as the troops appeared. Troops flitted through «>e - ' ' . A fIvMA fn fnllr If- women who had attended Mass The army’s main target was drizzle to take cover in dark- army spokesman said the shouted at a convoy roaring "Free Derry ’ the Bogside and ened doorways. Suburban lawns ^ troops suffered no casualties past; "W e’ll rise again and Creggan districts of Londonder- became a quagmire. the Irish Republi^n Arniy shot four gunmen during you'll know about it.” ry» ringed by concrete and iron At 4 a.m. a heavy force of in Londonderry, Belfast the night. The bodies of two "They'll be back,” women barricades, where the IRA has armored cars and armored per- and other areas before men were brought to a London- supporters of the IRA shouted, held unchallenged military sohnel carriers loaded with dawn today and encounter- derry hospital. ’The troops also flooded into sway for more than a year, troops nosed toward the barri- g(J almost no rsistance. It was the biggest military of- IRA havens in Armagh and At 4 a.m. -

At the Western Front 1918 - 2018

SALIENT CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AT THE WESTERN FRONT 1918 - 2018 100 years on Polygon Wood 2 SALIENT CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS AT THE WESTERN FRONT New England Regional Art Museum (NERAM), Armidale 23 March – 3 June 2018 www.neram.com.au Bathurst Regional Art Gallery 10 August – 7 October 2018 www.bathurstart.com.au Anzac Memorial, Sydney October 2018 – 17 February 2019 www.anzacmemorial.nsw.gov.au Bank Art Museum Moree 5 March – 29 April 2019 DEIRDRE BEAN www.bamm.org.au HARRIE FASHER PAUL FERMAN Muswellbrook Regional Arts Centre MICHELLE HISCOCK 11 May – 30 June 2019 ROSS LAURIE www.muswellbrookartscentre.com.au STEVE LOPES EUAN MACLEOD Tweed Regional Gallery 21 November 2019 – 16 February 2020 IAN MARR artgallery.tweed.nsw.gov.au IDRIS MURPHY AMANDA PENROSE HART LUKE SCIBERRAS Opposite page: (Front row, left to right) Wendy Sharpe, Harrie Fasher, Euan Macleod, Steve Lopes, Amanda Penrose Hart George Coates, Australian official war artist’s 1916-18, 1920, oil on canvas (Middle row, left to right) Ian Marr, Deirdre Bean, Ross Laurie, Michelle Hiscock, Luke Sciberras Australian War Memorial collection WENDY SHARPE (Back row, left to right) Paul Ferman, Idris Murphy 4 Salient 5 Crosses sitting on a pillbox, Polygon Wood Pillbox, Polygon Wood 6 Salient 7 The Hon. Don Harwin Minister for the Arts, NSW Parliament Standing on top of the hill outside the village of Mont St Quentin, which Australian troops took in a decisive battle, it is impossible not to be captivated From a population of fewer than 5 million, almost 417,000 Australian men by the beauty of the landscape, but also haunted by the suffering of those enlisted to fight in the Great War, with 60,000 killed and 156,000 wounded, who experienced this bloody turning point in the war. -

Becky Beasley

BECKY BEASLEY FRANCESCA MININI VIA MASSIMIANO, 25 20134 MILANO T +39 02 26924671 [email protected] WWW.FRANCESCAMININI.IT BECKY BEASLEY b. Portsmouth, United Kingdom 1975 Lives and works in St. Leonards on Sea (UK) Becky Beasley (b.1975, UK) graduated from Goldsmiths College, London in 1999 and from The Royal College of Art in 2002, lives and works in St. Leonards on sea. Forthcoming exhibitions include Art Now at Tate Britain, Spike Island, Bristol and a solo exhibition at Laura Bartlett Gallery, London. Beasley has recently curated the group exhibition Voyage around my room at Norma Mangione Gallery, Turin. Recent exhibitions include, 8TH MAY 1904 at Stanley Picker Gallery, London, P.A.N.O.R.A.M.A at Office Baroque, Antwerp and 13 Pieces17 Feet at Serpentine Pavillion Live Event. Among her most important group exhibitions: Trasparent Things, CCA Goldsmiths, London (2020), La carte d’après nature NMNM, Villa Paloma, Monaco (2010), The Malady of Writing, MACBA Barcelona, (2009), FANTASMATA, Arge Kunst, Bozen (2008), and Word Event, Kunsthalle Basel, Basel (2008). Gallery exhibitions BECKY BEASLEY Late Winter Light Opening 23 January 2018 Until 10 March 2018 Late Winter Light is an exhibition of works which This work, The Bedstead, shows the hotel room The show embraces all the media used by the reveals Beasley’s ongoing exploration of where Ravilious found himself confined by bad artist – photography, sculpture, and, most emotion and ambiguity in relation to everyday weather when he came to Le Havre in the spring recently, video– and touches on many of the life and the human condition. -

Magazine of the Families and Friends of the First AIF Inc

DIGGER “Dedicated to Digger Heritage” Above: The band of the 1st Australian Light Horse Regiment, taken just before embarkation in 1914. Those men marked with an ‘X’ were killed and those marked ‘O’ were wounded in the war. Photo courtesy of Roy Greatorex, the son of Trooper James Greatorex (later lieutenant, 1st LH Bde MG Squadron), second from right, back row. September 2018 No. 64 Magazine of the Families and Friends of the First AIF Inc Edited by Graeme Hosken ISSN 1834-8963 Families and Friends of the First AIF Inc Patron-in-Chief: His Excellency General the Honourable Sir Peter Cosgrove AK MC (Retd) Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia Founder and Patron-in-Memoriam: John Laffin Patrons-in-Memoriam: General Sir John Monash GCMG KCB VD and General Sir Harry Chauvel CGMG KCB President: Jim Munro ABN 67 473 829 552 Secretary: Graeme Hosken Trench talk Graeme Hosken. This issue A touching part of the FFFAIF tours of the Western Front is when Matt Smith leads a visit to High Tree Cemetery at Montbrehain, where some of the Diggers killed in the last battle fought by the AIF in the war are buried. In this issue, Evan Evans tells the story of this last action and considers whether it was necessary for the exhausted men of the AIF to take part. Andrew Pittaway describes how three soldiers had their burial places identified in Birr Cross Roads Cemetery, while Greg O’Reilly profiles a brave machine-gun officer. Just three of many interesting articles in our 64th edition of DIGGER. -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents 1970s: Out of Sculpture, Elena Crippa 1970s: Out of Sculpture Elena Crippa Abstract In the 1970s, the mobility of ideas, artists, and their work intensified. -

EWVA 4Th Full Proofxx.Pdf (9.446Mb)

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of Art, Design and Architecture 2019-04 Ewva European Women's Video Art in The 70sand 80s http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/16391 JOHN LIBBEY PUBLISHING All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. EWVA EuropeanPROOF Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s do not distribute PROOF do not distribute Cover image: Lydia Schouten, The lone ranger, lost in the jungle of erotic desire, 1981, still from video. Courtesy of the artist. EWVA European Women’s PROOF Video Art in the 70s and 80s Edited by do Laura Leuzzi, Elaine Shemiltnot and Stephen Partridge Proofreading and copyediting by Laura Leuzzi and Alexandra Ross Photo editing by Laura Leuzzi anddistribute Adam Lockhart EWVA | European Women's Video Art in the 70s and 80s iv British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data EWVA European Women’s Video Art in the 70s and 80s A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 9780 86196 734 6 (Hardback) PROOF do not distribute Published by John Libbey Publishing Ltd, 205 Crescent Road, East Barnet, Herts EN4 8SB, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected]; web site: www.johnlibbey.com Distributed worldwide by Indiana University Press, Herman B Wells Library – 350, 1320 E. -

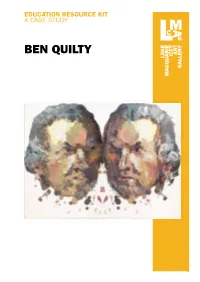

Ben Quilty: a Case Study(PDF, 558KB)

EDUCATION RESOURCE KIT A CASE STUDY BEN QUILTY 1 INTRODUCTION Written by Kate Caddey and published by Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery (LMCAG), this education kit is designed to assist senior secondary Visual Arts teachers and students in the preparation, appreciation and understanding of the case study component of the HSC syllabus. LMCAG is proud to support educators and students in the community with an ongoing series of case studies as they relate to the gallery’s exhibition program. This education kit is available in hard copy directly from the gallery or online at www.artgallery.lakemac.com.au/learn/schools. A CASE STUDY A series of case studies (a minimum of FIVE) should be undertaken with students in the Higher School Certificate (HSC) course. The selection of content for the case study should relate to various aspects of critical and historical investigations, taking into account practice, the conceptual framework and the frames. Emphasis may be given to a particular aspect of content although all should remain in play. Case studies should be 4–10 hours in duration in the HSC course. Cover: Ben Quilty Cook Rorschach 2009 NSW Board of Studies, Visual Arts Stage 6 Syllabus, 2012 oil on linen 140 x 190cm © the artist CONTENTS THE ARTIST 5 PRACTICE 7 Conceptual Practice 7 Explorations of masculinity and mortality 7 Humanitarianism and social issues 14 Australian identity and history 15 Material Practice 16 THE FRAMES 18 Artwork Analysis Using the Frames 18 Structural frame 18 Cultural frame 20 Subjective frame 21 Postmodern frame 23 THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 24 Artist 25 Audience 24 Artwork 24 World 24 PREVIOUS HSC EXAMINATION QUESTIONS RELEVANT TO THIS CASE STUDY 26 GLOSSARY 27 REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING 28 Websites 28 Videos 29 Articles and catalogues 30 A CASE STUDY BEN QUILTY 3 A CASE STUDY BEN QUILTY 4 THE ARTIST Ben Quilty in front ‘I am an Artist. -

Afternoon Art Club at Home Ben Quilty

Goulburn Regional Art Gallery Afternoon Art Club at Home Ben Quilty Goulburn Regional Art Gallery is supported by the NSW government through Create NSW About Afternoon Art Club at Home The Afternoon Art Club at Home has been developed to support all of our art club- bers during the COVID-19 closures. It is prepared by Janet Gordon, Outreach Of- ficer. Gordon has a Bachelor of Teaching (birth to 5yrs) and a Diploma in Children’s Services (Centre based care), with 20 years experience in early childhood educa- tion. Gordon has several years experience in relief-teaching the afternoon art club at Goulburn Regional Art Gallery. This Afternoon Art Club at Home explores Ben Quilty. I find Quilty’s work fascinating. I like the way the paint looks like it’s just waiting to drip and has me staring at it in anticipation. Who was Ben Quilty? Ben Quilty was born in Sydney in 1973 and now resides in Robertson, just up the highway. After finishing high school, Quilty graduated from Sydney College of Arts at the Uni- versity of Sydney with a Bachelor of Visual Arts in Painting. He didn’t finish his studies there. He went on to study at Western Sydney University graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 2002. In 2011 Quilty was stationed in Afghanistan with soldiers from the Australian Defence force. He was employed as an official war artist and quickly sketched and painted the daily lives and struggles of the soldiers. Art- works from this time are part of the Australian War Memorial’s National Collection. -

Disseminating Design: the Post-War Regional Impact of the Victoria & Albert Museum’S Circulation Department

DISSEMINATING DESIGN: THE POST-WAR REGIONAL IMPACT OF THE VICTORIA & ALBERT MUSEUM’S CIRCULATION DEPARTMENT JOANNA STACEY WEDDELL A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton in collaboration with the Victoria & Albert Museum for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2018 BLANK 2 Disseminating Design: The Post-war Regional Impact of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Circulation Department This material is unavailable due to copyright restrictions. Figure 1: Bill Lee and Arthur Blackburn, Circulation Department Manual Attendants, possibly late 1950s, MA/15/37, No. V143, V&A Archive, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Joanna Weddell University of Brighton with the Victoria and Albert Museum AHRC Part-time Collaborative Doctoral Award AH/I021450/1 3 BLANK 4 Thesis Abstract This thesis establishes the post-war regional impact of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Circulation Department (Circ) which sent touring exhibitions to museums and art schools around the UK in the period 1947-1977, an area previously unexplored to any substantial depth. A simplistic stereotypical dyad of metropolitan authority and provincial deference is examined and evidence given for a more complex flow between Museum and regions. The Introduction outlines the thesis aims and the Department’s role in the dissemination of art and design. The thesis is structured around questions examining the historical significance of Circ, the display and installation of Circ’s regional exhibitions, and the flow of influence between regions and museum. Context establishes Circ not as a straightforward continuation of Cole’s Victorian mission but as historically embedded in the post-war period. -

African Textiles in the V&A 1852- 2000

Title Producing and Collecting for Empire: African Textiles in the V&A 1852- 2000 Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/6141/ Date 2012 Citation Stylianou, Nicola Stella (2012) Producing and Collecting for Empire: African Textiles in the V&A 1852-2000. PhD thesis, University of the Arts London and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Creators Stylianou, Nicola Stella Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Producing and Collecting for Empire: African Textiles in the V&A 1852-2000 Nicola Stella Stylianou Submitted to University of the Arts London for PhD Examination October 2012 This is an AHRC funded Collaborative PhD between Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) at UAL and the Victoria and Albert Museum. Volume 1 Abstract Producing and collecting for Empire: African textiles in the V&A 1850-2000 The aim of this project is to examine the African textiles in the Victoria and Albert Museum and how they reflect the historical and cultural relationship between Britain and Africa. As recently as 2009 the V&A’s collecting policy stated ‘Objects are collected from all major artistic traditions … The Museum does not collect historic material from Oceania and Africa south of the Sahara’ (V&A 2012 Appendix 1). Despite this a significant number of Sub-Saharan African textiles have come into the V&A during the museum’s history. The V&A also has a large number of textiles from North Africa, both aspects of the collection are examined.