African Textiles in the V&A 1852- 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruskin and South Kensington: Contrasting Approaches to Art Education

Ruskin and South Kensington: contrasting approaches to art education Anthony Burton This article deals with Ruskin’s contribution to art education and training, as it can be defined by comparison and contrast with the government-sponsored art training supplied by (to use the handy nickname) ‘South Kensington’. It is tempting to treat this matter, and thus to dramatize it, as a personality clash between Ruskin and Henry Cole – who, ten years older than Ruskin, was the man in charge of the South Kensington system. Robert Hewison has commented that their ‘individual personalities, attitudes and ambitions are so diametrically opposed as to represent the longitude and latitude of Victorian cultural values’. He characterises Cole as ‘utilitarian’ and ‘rationalist’, as against Ruskin, who was a ‘romantic anti-capitalist’ and in favour of the ‘imaginative’.1 This article will set the personality clash in the broader context of Victorian art education.2 Ruskin and Cole develop differing approaches to art education Anyone interested in achieving artistic skill in Victorian England would probably begin by taking private lessons from a practising painter. Both Cole and Ruskin did so. Cole took drawing lessons from Charles Wild and David Cox,3 and Ruskin had art tuition from Charles Runciman and Copley Fielding, ‘the most fashionable drawing master of the day’.4 A few private art schools existed, the most prestigious being that run by Henry Sass (which is commemorated in fictional form, as ‘Gandish’s’, in Thackeray’s novel, The Newcomes).5 Sass’s school aimed to equip 1 Robert Hewison, ‘Straight lines or curved? The Victorian values of John Ruskin and Henry Cole’, in Peggy Deamer, ed, Architecture and capitalism: 1845 to the present, London: Routledge, 2013, 8, 21. -

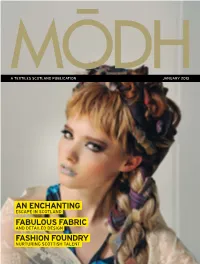

Modh-Textiles-Scotland-Issue-4.Pdf

A TEXTILES SCOTLAND PUBLICATION JANUARY 2013 AN ENCHANTING ESCAPE IN SCOTLAND FABULOUS FABRIC AND DETAILED DESIGN FASHION FOUNDRY NURTURING SCOTTISH TALENT contents Editor’s Note Setting the Scene 3 Welcome from Stewart Roxburgh 21 Make a statement in any room with inspired wallpaper Ten Must-Haves for this Season An Enchanting Escape 4 Some of the cutest products on offer this season 23 A fashionable stay in Scotland Fabulous Fabric Fashion Foundry 6 Uncovering the wealth of quality fabric in Scotland 32 Inspirational hub for a new generation Fashion with Passion Devil is in the Detail 12 Guest contributor Eric Musgrave shares his 38 Dedicated craftsmanship from start to fi nish thoughts on Scottish textiles Our World of Interiors Find us 18 Guest contributor Ronda Carman on why Scotland 44 Why not get in touch – you know you want to! has the interiors market fi rmly sewn up FRONT COVER Helena wears: Jacquard Woven Plaid with Herringbone 100% Merino Wool Fabric in Hair by Calzeat; Poppy Soft Cupsilk Bra by Iona Crawford and contributors Lucynda Lace in Ivory by MYB Textiles. Thanks to: Our fi rst ever guest contributors – Eric Musgrave and Ronda Carman. Read Eric’s thoughts on the Scottish textiles industry on page 12 and Ronda’s insights on Scottish interiors on page 18. And our main photoshoot team – photographer Anna Isola Crolla and assistant Solen; creative director/stylist Chris Hunt and assistant Emma Jackson; hair-stylist Gary Lees using tecni.art by L’Oreal Professionnel and the ‘O’ and irons by Cloud Nine, and make-up artist Ana Cruzalegui using WE ARE FAUX and Nars products. -

Spring | Sum M Er 2020 Introducing The

SUMMER 2020 SUMMER | SPRING INTRODUCING THE baekgaardUSA.com WOMEN'S COLLECTION Peer Baekgaard on his voyage from Denmark to America in 1951 THE BAEKGAARD STORY In 1951, Peer Baekgaard came to New York City from Denmark with $127 in his pocket and one big dream. He managed to sell his boats to FAO Schwarz, leading to the development of a unique giftware business. This lead to Peer launching a giftware business specializing in fine gifts and accessories. In the late 1980's, as the President of the Chicago Gift Mart, he met a woman starting a business of her own. In 1990, he and Barbara Bradley married and remained co-owners of Baekgaard Ltd. until Peer's passing in 2007. Barbara Bradley Baekgaard, co-founder of Vera Bradley, was looking for the same function and high-quality bags for the men in her life. She decided to re-launch Baekgaard USA in 2018 with a selection of travelbags, totes and accessories for both men and women who are looking for everyday essentials to take them from work and school to weekend getaways. The SPRING combination of ingenuity, functionality and can-do spirit of both Barbara and Peer | SUMMER 2020 SUMMER lives on in every piece Baekgaard creates. DANISH AMERICAN We invite you to explore our entire line of BORN BY DESIGN fine bags and accessories.Skol! TATTERSALL NEW PLAID COLBY CROSSBODY NEW The perfect sized crossbody for BROWN LEATHER STYLES all your needs: travel, shopping or evenings out. The main compartment has a zippered pocket and 3 credit BLACK card slots. -

Weaving Twill Damask Fabric Using ‘Section- Scale- Stitch’ Harnessing

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research Vol. 40, December 2015, pp. 356-362 Weaving twill damask fabric using ‘section- scale- stitch’ harnessing R G Panneerselvam 1, a, L Rathakrishnan2 & H L Vijayakumar3 1Department of Weaving, Indian Institute of Handloom Technology, Chowkaghat, Varanasi 221 002, India 2Rural Industries and Management, Gandhigram Rural Institute, Gandhigram 624 302, India 3Army Institute of Fashion and Design, Bangalore 560 016, India Received 6 June 2014; revised received and accepted 30 July 2014 The possibility of weaving figured twill damask using the combination of ‘sectional-scaled- stitched’ (SSS) harnessing systems has been explored. Setting of sectional, pressure harness systems used in jacquard have been studied. The arrangements of weave marks of twill damask using the warp face and weft face twills of 4 threads have been analyzed. The different characteristics of the weave have been identified. The methodology of setting the jacquard harness along with healds has been derived corresponding to the weave analysis. It involves in making the harness / ends in two sections; one section is to increase the figuring capacity by scaling the harness and combining it with other section of simple stitching harnessing of ends. Hence, the new harness methodology has been named as ‘section-scale-stitch’ harnessing. The advantages of new SSS harnessing to weave figured twill damask have been recorded. It is observed that the new harnessing methodology has got the advantages like increased figuring capacity with the given jacquard, less strain on the ends and versatility to produce all range of products of twill damask. It is also found that the new harnessing is suitable to weave figured double cloth using interchanging double equal plain cloth, extra warp and extra weft weaving. -

The Manufacture of Paper

/°* '^^^n^ //i,- '^r. c.^" ^'IM^"* *»^ A^ -h^" .0^ V ,<- ^.. A^^ /^-^ " THE MANUFACTURE OF PAPER BY R. W. SINDALL, F.C.S. CHEMIST CONSULTING TO THE WOOD PULP AND PAPER TRADES ; LECTURER ON PAPER-MAKING FOR THE HERTFORDSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL, THE BUCKS COUNTY COUNCIL, THE PRINTING AND STATIONERY TRADES AT EXETER HALL, 1903-4, THE INSTITUTE OF PRINTERS ; TECHNICAL ADVISER TO THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA, 1905 AUTHOR OF "paper TECHNOLOGY," " THE SAMPLING OF WOOD PULP " JOINT AUTHOR OF " THE C.B.S. UNITS, OR STANDARDS OF PAPER TESTING," " THE APPLICATIONS OF WOOD PULP," ETC. WITH ILLUSTRATIONS, AND A BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS RELATING TO CELLULOSE AND PAPER-MAKING ^^RlFFeo^ ^^ ^, 11^ OCT 3 11910 ^^f-40 ^\^c> A BU\ lo\' NEW YORK D. VAN NOSTRAND COMPANY 23 MURRAY AND 27 WARREN STREETS 1908 By trassf»r trom U. S. Tariff Boarri 1012 /(o'?'<Q / PREFACE •Papee-making, in common with many other industries, is one in which both engineering and chemistry play important parts. Unfortunately the functions of the engineer and chemist are generally regai^dedi •a&n.inelepejident of one another, so that the chemist ife^o^ify e^llfeS-iii-hy the engineer when efforts along the lines of nlecTianical improvement have failed, and vice versa. It is impossible, however, to draw a hard and fast line, and the best results in the art of paper-making are only possible when the manufacturer appreciates the fact that the skill of both is essential to progress and commercial success. In the present elementary text-book it is only proposed to give an outline of the various stages of manufacture and to indicate some of the improvements made during recent years. -

Appendix 1 Sources

APPENDIX 1 SOURCES UMIST: DEPARTMENT OF TEXTILES Most of the work described in this book comes from research in the Department of Textiles, UMIST, under the direction of Professor John Hearle. It started with the purchase of a scanning electron microscope with a grant from the Science Research Council in 1967, together with five-year funding for an experimental officer and a technician. Since 1972, the staff have been supported by general UMIST funds; a second grant from SERC enabled a replacement SEM to be bought in 1979; industrial sponsors, listed below, have contributed through membership of the Fibre Fracture Research Group; special research grants have been made by the Ministry of Defence (SCRDE, Colchester, and RAE, Farnborough) and jointly by the Wool Research Organization of New Zealand (WRONZ) and the Wool Foundation (IWS); and other research programmes and contract services have contributed indirectly to our knowledge. Pat Cross was the first SEM experimental officer and she was followed in 1969 by Brenda Lomas, who retired in 1990. Trevor Jones then took on responsibility for microscopy in the Department of Textiles in addition to photography. Over the years, many staff and students have contributed to the research. Their names are given below. Some have worked wholly on fibre fracture problems. Others have used fracture studies as an incidental element in their work. PERSONNEL The following people at UMIST have contributed to the research. Academic staff J.D. Berry Aspects of fibre breakage CP. Buckley Mechanics of tensile fracture, general direction C. Carr Fabric studies W.D. Cooke Pilling in knitwear, conservation studies G.E. -

Printing of Pigments and Special Effects

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 ISP 1017 PRINTING OF PIGMENTS AND SPECIAL EFFECTS This report is sponsored by the Importer Support Program and written to address the technical needs of product sourcers. Copyright 2007, Cotton Incorporated INTRODUCTION Of the print systems used on cotton in the textile industry, pigment printing accounts for as much as seventy percent of the total1. This system requires no pre or post treatment other than drying the fabric. The color gamut is wide, and the sharpness of prints is excellent. Pigments do not react with the cotton fiber and must be adhered to the fabric with a film forming binder, which may detract from the hand of the fabric. However, advances in binder systems have made positive contributions to print performance. Special effects are used in addition to or in combination with pigments to impart a unique look to fabrics. Some of the special effects examined in this bulletin include resist, discharge, and burnout techniques. Alternative pigment types such as thermotropic, phototropic, puff, and plastisol technologies will also be described. PIGMENT PRINTING A textile pigment print system includes the following parameters: • Pigment: A pigment colorant is a colored organic substance that is not readily soluble in most common solvents and imparts coloration to textile substrates only when incorporated with an adequate binder system. • Binder: A pigment binder is the latex polymer resin that forms a three-dimensional film on the surface of the fiber. This film contains the dispersion of textile pigment and will act to adhere the pigment to the surface of the substrate. -

Mathematics in African History and Cultures

Paulus Gerdes & Ahmed Djebbar MATHEMATICS IN AFRICAN HISTORY AND CULTURES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY African Mathematical Union Commission on the History of Mathematics in Africa (AMUCHMA) Mathematics in African History and Cultures Second edition, 2007 First edition: African Mathematical Union, Cape Town, South Africa, 2004 ISBN: 978-1-4303-1537-7 Published by Lulu. Copyright © 2007 by Paulus Gerdes & Ahmed Djebbar Authors Paulus Gerdes Research Centre for Mathematics, Culture and Education, C.P. 915, Maputo, Mozambique E-mail: [email protected] Ahmed Djebbar Département de mathématiques, Bt. M 2, Université de Lille 1, 59655 Villeneuve D’Asq Cedex, France E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Cover design inspired by a pattern on a mat woven in the 19th century by a Yombe woman from the Lower Congo area (Cf. GER-04b, p. 96). 2 Table of contents page Preface by the President of the African 7 Mathematical Union (Prof. Jan Persens) Introduction 9 Introduction to the new edition 14 Bibliography A 15 B 43 C 65 D 77 E 105 F 115 G 121 H 162 I 173 J 179 K 182 L 194 M 207 N 223 O 228 P 234 R 241 S 252 T 274 U 281 V 283 3 Mathematics in African History and Cultures page W 290 Y 296 Z 298 Appendices 1 On mathematicians of African descent / 307 Diaspora 2 Publications by Africans on the History of 313 Mathematics outside Africa (including reviews of these publications) 3 On Time-reckoning and Astronomy in 317 African History and Cultures 4 String figures in Africa 338 5 Examples of other Mathematical Books and 343 -

Low Crown Visor High Crown Visor

LOW CROWN VISOR VISOR SPECIFICATIONS • Low Crown (TV1) • Velcro Adjustable Closure Only • Pre-Curved Visor Only FABRIC OPTIONS VISOR 02 • Cotton Twill Black / Texas Orange Cotton Twill • Level Three • Army, Tiger, Snow Camo (TV103): Woven Label w/ Zig-Zag Stitch (Drop • Digital Camo (Available in 7 Colors) #TG149) + Heavy Wash Upgrade • Lightweight Cotton (Oxford or Solid) • Active Heather • Performance Mesh • Performance Wick • ProHex • ProMax • Nylon VISOR 01 VISOR 03 • UV Lite Vegas UV Lite / Black / White Perforated UV Lite Cut & Sew • Level One Red / Navy / White Performance Mesh • Level (TV101): Raised & Flat Embroidery (Drop #TG098) + Double Visor Cut One (TV101): Raised & Flat Embroidery (Drop • Perforated UV Lite & Sew Upgrade (VCS009) #TG112) + Double Panel Cut & Sews Upgrade • Mossy Oak Break-Up Country® (FCS002/FCS003) + Visor Sandwich Upgrade • Mossy Oak Shadow Grass Blades® EMBELLISHMENT LEVELS • Specialty Fabrics (See Page 36) LEVEL ONE (TV101) LEVEL TWO (TV102) • Sport Mesh (Back Panels Only) 1 Front Embroidery Option 1 Front Embroidery Option • Trucker Mesh (Back Panels Only) + 1 Additional Graphic Location LEVEL THREE (TV103) LEVEL FOUR (TV104) ADDITIONAL OPTIONS 1 Front Custom Applique 1 Front Custom Applique • Custom Add-Ons + 1 Additional Graphic Location HIGH CROWN VISOR VISOR SPECIFICATIONS • High Crown (TV3) • Metal Slider Adjustable Closure Only • Pre-Curved Visor Only • Terry Cloth Headband VISOR 05 FABRIC OPTIONS Maroon Performance Mesh • Level One (TV301): Raised Embroidery (Font: Ballpark • Cotton Twill Weiner) -

Final Changes CFS LABEX

Project ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums : a transnational comparison’ Hervé Inglebert, University of Paris Ouest Nanterre La Défense ("The Past in the Present") Sandra Kemp, Victoria and Albert Museum ("Care For Future") 1-Topic and relevance to the Care for the Future and Labex Programmes Since the late eighteenth century, alongside Enlightenment’s philosophy on human rights, Western scholars have conceptualised human universality in universal histories and universal museums. In its investigation of the evolution of museum collections, the ‘Universal Histories and Universal Museums’ project has a clear correlation with the third objective of the ‘The Past in the Present’ and the ‘Care for the Future’ programmes: the mediation, and of the cultural and social appropriation of the past. Looking at the history of museum collections is one of the ways in which we can examine how history is made, displayed and disseminated through the uses, legacies and representations of the past. Our research will highlight the constituent features of encyclopaedic knowledge about Western universalities from the nineteenth century to the present day. It will also examine the assumptions and limitations of such understanding. In particular, the project seeks to address questions regarding the representation of the diversity of cultures that define human universality, the articulation of historical and anthropological approaches to the description of humanity and the influence of social knowledge practices on the structuring of universal knowledge. The project also considers how ways thinking about the past may help us to prepare for a global future that incorporates more diverse universalities. The first phase of the project will combine critical investigation through four workshops and two historical case studies, based in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro. -

Coats® Tre Cerchi Vero™ Coats Tre Cerchi Vero Is a 100% Cotton Thread Made from Premium Quality, Sustainable Raw Materials

tre cerchi vero 100% COTTON Coats® Tre Cerchi Vero™ Coats Tre Cerchi Vero is a 100% cotton thread made from premium quality, sustainable raw materials. Our raw materials are sourced with care for an eco- friendly sewing thread that adds beautiful, lustrous seams to a wide range of products. Developed with long-staple fibres, Tre Cerchi Vero combines the natural look of cotton with high-performance thread. WHY CHOOSE TRE CERCHI VERO? MAIN USES: Tre Cerchi Vero is a top-of-class mercerised cotton sewing thread • Denim available in a selected range of colours for general sewing and • T-shirts available as unbleached for garment dye end-use. • Natural look of cotton thread • Post dye garments • Öko-Tex Standard 100, class I certified • Workwear • Meets Coats restricted substance list • Embroidery and decorative top stitching • Globally available • High quality leather jackets and other • Suitable for vegan requirements products made from leather www.coats.com tre cerchi vero Coats Tre Cerchi Vero PRODUCT RANGE CHEMICAL PROPERTIES Strength Elongation % Art / Tkt Tex Ticket Length Ply Acids: Sensitive to mineral acids especially if halogenated cN Min - Max 770C 008 270 8 1500m 9 5640 4 - 15 Alkalis: Swells in caustic mercerising but is not damaged 770C 018 105 18 5000m 3 3050 6 - 11 Generally unaffected by most organic solvents. Generally unaffected by sodium hypochlorite, sodium perborate 770C 024 80 24 5000m 3 1900 4 - 10 Organic solvents: and peroxide bleaches under controlled conditions. There 100% 770C 030 60 30 5000m 3 1800 4 - 12 is -

A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War M

Bold Impressions: A Comparative Analysis of Artist Prints and Print Collecting at the Imperial War Museum and Australian War Memorial Alexandra Fae Walton A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University, June 2017. © Copyright by Alexandra Fae Walton, 2017 DECLARATION PAGE I declare that this thesis has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been submitted, in whole or in part, in any previous application for a degree. Except where stated otherwise by reference or acknowledgement, the work presented is entirely my own. Acknowledgements I was inspired to write about the two print collections while working in the Art Section at the Australian War Memorial. The many striking and varied prints in that collection made me wonder about their place in that museum – it being such a special yet conservative institution in the minds of many Australians. The prints themselves always sustained my interest in the topic, but I was also fortunate to have guidance and assistance from a number of people during my research, and to make new friends. Firstly, I would like to say thank you to my supervisors: Dr Peter Londey who gave such helpful advice on all my chapters, and who saw me through the final year of the PhD; Dr Kylie Message who guided and supported me for the bulk of the project; Dr Caroline Turner who gave excellent feedback on chapters and my final oral presentation; and also Dr Sarah Scott and Roger Butler who gave good advice from a prints perspective. Thank you to Professor Joan Beaumont, Professor Helen Ennis and Professor Diane Davis from the Australian National University (ANU) for making the time to discuss my thesis with me, and for their advice.