E-N Fo N a D Vii.Mmxiii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Könyv-11:Elrendezés 1.Qxd

International Yearbook of Aesthetics Volume 19, 2017 RETRACING THE PAST Historical continuity in aesthetics from a global perspective Edited by Zoltán Somhegyi International Association for Aesthetics Association Internationale d’Esthétique RETRACING THE PAST Historical continuity in aesthetics from a global perspective Edited by Zoltán Somhegyi The selection of essays in the 19th Yearbook of the International Association for Aesthetics aims to analyse the phenomenon of retracing the past, i.e. of identifying the signs, details and processes of the creative re-interpretation of long-lasting traditions both in actual works of art and in aesthetic thought, hence where the historical interconnectedness and the influence of earlier sources can appear. ISBN: 978-0-692-04826-9 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR AESTHETICS Retracing the past INTERNATIONAL YEARBOOK OF AESTHETICS Volume 19, 2017 INTERNATIONAL YEARBOOK OF AESTHETICS Volume 19, 2017 Edited by Zoltán Somhegyi RETRACING THE PAST Historical continuity in aesthetics from a global perspective International Association for Aesthetics Association Internationale d’Esthétique Copyright: the Authors and the International Association for Aesthetics Acknowledgement: The Publication Committee of the International Association for Aesthetics, Tyrus Miller, Curtis Carter and Ales Erjavec, for reviewing the essays. Every effort has been made to obtain permissions to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Cover design: Ahmad Manar Laham Editor: Zoltán Somhegyi Published by the International Association for Aesthetics http://www.iaaesthetics.org/ Santa Cruz, California, 2017 ISBN: 978-0-692-04826-9 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Zoltán Somhegyi 1. The paradox of mimesis 9 In connection with Aristotle Béla Bacsó 2. Reflections on the subject of Antiquity and the future 23 Raffaele Milani 3. -

12 - October 2009 the Note from CONE the Editor

THE CONE COLLECTOR #12 - October 2009 THE Note from CONE the editor COLLECTOR It is always a renewed pleasure to put together another issue of Th e Cone Collector. Th anks to many contributors, we have managed so far to stick to the set schedule – André’s eff orts are greatly to be Editor praised, because he really does a great graphic job from the raw ma- António Monteiro terial I send him – and, I hope, to present in each issue a wide array of articles that may interest our many readers. Remember we aim Layout to present something for everybody, from beginners in the ways of André Poremski Cone collecting to advanced collectors and even professional mala- cologists! Contributors Randy Allamand In the following pages you will fi nd the most recent news concern- Kathleen Cecala ing new publications, new taxa, rare species, interesting or outstand- Ashley Chadwick ing fi ndings, and many other articles on every aspect of the study Paul Kersten and collection of Cones (and their relationship to Mankind), as well Gavin Malcolm as the ever popular section “Who’s Who in Cones” that helps to get Baldomero Olivera Toto Olivera to know one another better! Alexander Medvedev Donald Moody You will also fi nd a number of comments, additions and corrections Philippe Quiquandon to our previous issue. Keep them coming! Th ese comments are al- Jon Singleton ways extremely useful to everybody. Don’t forget that Th e Cone Col- lector is a good place to ask any questions you may have concerning the identifi cation of any doubtful specimens in your collections, as everybody is always willing to express an opinion. -

On Adriaen Coorte, Elias Van Den Broeck, and the Je Ne Sais Quoi of Painting

Volume 8, Issue 2 (Summer 2016) Sublime Still Life: On Adriaen Coorte, Elias van den Broeck, and the Je ne sais quoi of Painting Hanneke Grootenboer [email protected] Recommended Citation: Hanneke Grootenboer, “Sublime Still Life: On Adriaen Coorte, Elias van den Broeck, and the Je ne sais quoi of Painting,” JHNA 8:2 (Summer 2016), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2016.8.2.10 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/sublime-still-life-adriaen-coorte-elias-van-den-broeck-je-ne- sais-quoi-painting/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 7:2 (Summer 2015) 1 SUBLIME STILL LIFE: ON ADRIAEN COORTE, ELIAS VAN DEN BROECK, AND THE JE NE SAIS QUOI OF PAINTING Hanneke Grootenboer This paper explores the ways in which Adriaen Coorte (1665–1707) in his still lifes presents philosophical reflections on sublimity. I argue that throughout his oeuvre Coorte, despite the unusually small size of his works (often not much larger than a postcard), can be seen searching for the limits of painting. Special attention is given to the unconven- tional way in which he animates his fruits and shells, presenting them as if they are actors in an indefinable place, and the rather extreme contradictions in dimension and scale he employs. I conclude by referring to another type of sublimity in painting in a truly genuine fusion of painting and collage in a forest piece by Elias van den Broeck. -

Cone Shell, (Conus Marmoreus) Rembrandt Van Rijn 1650, Etching, Engraving and Drypoint

CONE SHELLS Cone Shell, (Conus marmoreus) Rembrandt van Rijn 1650, Etching, engraving and drypoint. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Holland. Introduction ● Cone shell animals are a group of carnivorous marine gastropods. ● Worldwide there are about 300 species. There are about 80 species within Australian coastal waters. ● These animals can cause potentially lethal envenomation. ● They are prized by shell collectors the world over because of their intricate patterning and beauty, (see appendix 1 below). Description Their scientific taxonomy is: Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Mollusca. Class: Gastropoda. Subclass: Orthogastropoda. Superorder: Caenogastropoda. Order: Sorbeoconcha. Suborder: Hypsogastropoda. Infraorder: Neogastropoda. Superfamily: Conoidea. Family: Conidae Conus textile (photo by Bruce Livett, University of Melbourne) Habitat ● The cone shell gastropods are nocturnal feeders, rarely being seen during daylight hours. ● During the day they generally lie buried beneath the sand. ● Australian species inhabit warm tropical and subtropical coastal waters. ● They are shallow water dwellers mainly inhabiting tidal reefs. ● They are especially seen around the Great Barrier Reef. ● Colder southern waters have smaller worm eating species which are not dangerous. Classification The cone shell species as a group are readily recognized by their conic shape. They may be classified according to their prey and size. The larger species prey on fish, while the intermediate sized species prey on molluscs and the smaller species on worms. The large species may grow up to 25 cm in length. 1. Piscivorous: Fish eaters, including: ● Conus striatus ● Conus geographus ● Conus magnus ● Conus catus ● Conus tulipa 2. Molluscivorous: Mollusk eaters, including: ● Conus textile ● Conus marmoreus ● Conus pennaceus 3. Vermivorous: Worm eaters. ● There are many including: C.imperialis/ C.eburneus / C.quercinus / C.lividus / C.tessulatus / C.ventricosus / C.parvatus / C.rattus / C.flavidus / C.generalis / C.arenatus Venom All species are venomous to varying degrees. -

CHECKLIST the Thaw Collection of Master Drawings: Acquisitions

CHECKLIST The Thaw Collection of Master Drawings: Acquisitions Since 2002 January 23 through May 3, 2009 FRANCESCO DI GIORGIO MARTINI (FRANCESCO MAURIZIO DI GIORGIO DI MARTINO POLLAIUOLO) Siena 1439–1502 Siena Design of a Temple Verso: Standing Female Figure Pen and brown ink 10 15/16 x 7 1/4 inches (278 x 183 mm) FEDERICO BAROCCI Urbino 1535–1612 Urbino Head of a Bearded Man in Profile to the Right, 1588–91 Black, red, white, and brown chalk, on blue paper faded to blue-green; laid down on a Cobenzl mount 12 1/4 x 10 1/16 inches; 311 x 255 mm ALESSANDRO MAGNASCO Genoa 1667–1749 Genoa Three Male Figures Resting, One Playing a Pipe Brush and brown ink, over black chalk, heightened with white gouache; a large strip along upper left edge cut away 7 3/4 x 16 3/4 inches (197 x 440 mm) Numbered on the strip added along upper left edge, in pen and brown ink, 26. ANONYMOUS, Sixteenth century, German (probably Augsburg) Three of Seven Maidens Placing a Wreath on a Knight (Maximilian I?), ca. 1515 Pen and black ink, with some black chalk, over an unrelated sketch in black chalk, with a ruled line in black ink at left and traces of framing line along right edge 13 x 8 7/8 inches (330 x 225 mm) Inscribed on verso, in pen and brown ink, in an old hand, [F]reydal [cropped]. Watermark: Cow skull surmounted by a crosier with entwined serpent [close to Briquet 15376: Rattenburg, 1498; 15379: Nurembuerg, 1524; 15395: Munich, 1508]. -

ABSTRACTS Another Horizon Session 1 Asher E. Miller, Assistant

ABSTRACTS Another Horizon Session 1 Asher E. Miller, Assistant Curator, Department of European Paintings The Metropolitan Museum of Art Northerners in Italy: Interaction, Transmission, Collaboration The point of departure for this talk is the Metropolitan Museum’s holdings of early nineteenth-century paintings and oil sketches by northern European artists working in Rome and Naples. Featuring works by figures ranging from Eckersberg and Koch to Catel and Granet, as well as their younger contemporaries, the Met’s collection was formed in recent years through a combination of curatorial initiative and the passion of local private collectors: it is, therefore, still in its youth. This presentation addresses questions of interaction, transmission, and collaboration between northern artists stemming from the research and display of these pictures. Specific areas of focus include artists of various national origins looking closely at the same iconic motifs, artists learning from one another’s methods and works, and artistic partnerships, notably between Heinrich Reinhold and Johann Joachim Faber, who sketched together at Olevano Romano in the early 1820s. Jens Peter Munk, MA (History of Art) Copenhagen Life among foreign artists in Rome as seen from a Danish perspective In my monograph on Danish Golden Age painter Jørgen Roed (2013) I dedicated a chapter to the life of Danish artists in Rome at that time. I focused in detail on their living and working conditions and their interaction with the local artistic environment as well as with other foreign artists staying in the city for an extended period of time. In this paper I wish to touch on some aspects of this vast theme. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} So Many Olympic Exertions by Anelise Chen Shells and Skulls

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} So Many Olympic Exertions by Anelise Chen Shells and Skulls. Typical of her species, the clam deactivated all of her social-media accounts on her thirtieth birthday and headed to the sea, not wanting anyone to wish her well. She was unable to explain this urge to hide on what most considered a momentous transition—thirty!—a day that’s usually reserved for last-hurrah debauchery. Instead, she Googled cabin rentals in Sag Harbor, where she and her husband would be unlikely to run into anyone they knew. On the drive out, a misty rain cloaked the empty highway. It rained all night, so they stayed in, drank bourbon, and watched The Shining in bed. The next morning, when she went out for a jog along the shore, the liminal space between sea and sky looked fuzzy, indistinct. She searched for something to latch on to. In the city, she tended to look up, searching for scalloped edges and glimpses of figures in lit windows, but by the sea, she looked at the sand. Whatever she picked up she put back down, knowing from experience that these objects would never be as beautiful as they were at first glance, half submerged and luminous in the frayed light. She couldn’t explain it then, the urge to hide on one’s birthday, but recently she read a passage in Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost about the molting behavior of hermit crabs that explained it perfectly. Hermit crabs have soft, vulnerable bodies, so they scavenge for shells left behind by mollusks. -

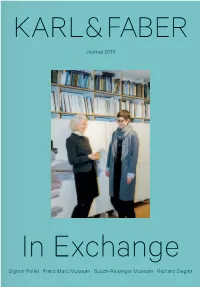

Journal 2019 Sigmar Polke · Franz Marc Museum

KARL&FABER Journal 2019 In Exchange Sigmar Polke · Franz Marc Museum · Busch-Reisinger Museum · Richard Ziegler Dear Reader, The current issue of our journal specifically examines the exchange KARL&FABER maintains with museums and institutions. Ultimately, such insti- tutions thrive because of the people who work in these places and/or those who support them. By focusing on them, it becomes clear once more that col- lectors and institutions, dealers and auction houses all have an extremely sym- biotic relationship that is not always tension-free, but for this, always remains exciting. KARL&FABER keeps close ties with the Franz Marc Museum in Kochel am See and the Busch-Reisinger Museum in Cambridge, near Boston (USA). In our title story, you will learn what strategies their two women museum directors develop in order to achieve distinction alongside the big players. Our column “From KARL&FABER to the Museum” explains to you how a painting by Hein- rich Reinhold and a photograph by Sigmar Polke from our past auctions found their ways to the museum. What is art worth? This question persists as an evergreen: An illustrious discussion round took a stand on this topic last summer in our building. You may well be surprised when you read the summary of the new and astonishing views! We feel privileged to rely on an increasing number of new customers who entrust to us their works of art. This also leads to new sales channels as well as to a further strengthening of our Contemporary Art Department, as you can gather from the various articles in our journal. -

8 List of Exhibited Works 08.05.2018

08.05.2018 LIST OF EXHIBITED WORKS Page 1 / 8 Andreas Achenbach Landscape with Runestone, 1841 (cat. 92) Oil on canvas Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Neue Pinakothek, München August Wilhelm Ahlborn Large Oak near Walkenried, 1837 (cat. 93) Oil on canvas Pommersches Landesmuseum, Greifswald Ernst Barlach Wanderer in the Wind, 1927 (cat. 124) Charcoal on paper Ernst Barlach Stiftung Güstrow Ernst Barlach Wanderer in the Wind, 1934 (cat. 125) Oak Ernst Barlach Stiftung Güstrow Ernst Barlach Resting Wanderer (Theodor Däubler), 1910 (cat. 66) Plaster, coloured Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie Ernst Barlach The Stroller, 1912 (cat. 122) Stucco, coloured Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie Press Contact Heinrich Beck Exhibition Looking into the Etsch Valley, 1839 (cat. 76) Dr. Katharina von Chlebowski Oil on wood Private ownership Carlo Paulus TEL +49 30 26 39 488 0 Wilhelm Bendz FAX +49 30 26 39 488 11 Mountain Landscape, ca. 1831 (cat. 54) [email protected] Oil on canvas www.freunde-der-nationalgalerie.de Den Hirschsprungske Samling, Kopenhagen Press Contact Karl Eduard Biermann Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Wetterhorn Peak, 1830 (cat. 18) Generaldirektion Oil on canvas Stauffenbergstraße 41 Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie 10785 Berlin Karl Eduard Biermann Mechtild Kronenberg The Finstermünz Pass in Tyrol, 1830 (cat. 17) Press, Communication, Sponsorship Oil on canvas TEL +49 30 266 42 34 01 Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie FAX +49 30 266 42 34 09 Carl Blechen [email protected] Self-Portrait, after 1825 (cat. 48) www.smb.museum/presse Oil on canvas on cardboard Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie Fiona Geuss Press officer Nationalgalerie Carl Blechen TEL +49 30 39 78 34 17 Draughtsman Sitting in the Grass (cat. -

LGT Vaduz 16 Nature As a Source of Inspiration

LGT VADU Z How art exemplifies our values 1 2 LGT VADU Z How art exemplifies our values LGT Bank Ltd., Herrengasse 12, FL-9490 Vaduz, www.lgt.li 3 Publisher LGT Bank Ltd., Herrengasse 12, FL-9490 Vaduz Concept, layout and editorial office Birgit Schmidt, Art Historian, Vienna LGT Group Marketing & Communications Translation Syntax Translations Ltd, Thalwil Print BVD Druck+Verlag AG, Schaan Lithographer Prepair Druckvorstufen AG, Schaan Picture credits LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna Paul Trummer, TravelLightart, Mauren Cover image Bauer brothers, Hortus Botanicus, detail from “Lilium candidum L.,” c. 1778 4 Contents Editorial 5 Lasting values 6 Successful art collectors and asset managers have similar qualities in common. Renaissance 8 Drawing inspiration from newly discovered artifacts and architecture from the ancient world, new ways of seeing the human form and the natural world find their way into art. Side story: Self-portrait of the artist 16 Baroque 19 Architecture, painting and sculpture are characterized by a strong sense of movement and sensuous extravagance. Side story: The dispute over the carriage 23 Classicism 34 As in the Renaissance, artists turn to the aesthetics of the ancient world for their touchstones. Elegance, grace and restraint are regarded as the ideals of the time. Side story: The Chinese pavilion 40 Biedermeier 48 The seemingly commonplace and the idyllic private sphere become the focus of attention. Artists look to nature and the wonders of reality for inspiration. Side story: Shared experiences of nature 60 5 6 Dear Client, Over the past few centuries, our family has built up a unique collection of artworks which we employ quite consciously in our marketing and communications strategy for LGT. -

Miszellaneen Miscellanea

miszellaneen MISCELLANEA c.g. boerner in collaboration with harris schrank fine prints Israhel van Meckenem ca. 1440–45 – d. Bocholt 1503 1. Die Auferstehung – The Resurrection (after the Master E.S.) ca. 1470 engraving with extensive hand-coloring in red, blue, green, reddish-brown and gold leaf; 94 x 74 mm (3 11�16 x 2 ⅞ inches) Lehrs and Hollstein 140 provenance C.G. Boerner, Leipzig, sale 153, May 3–4, 1927, lot 43 sub-no. 49 (ill. on plate 3) S.F.C. Wieder, Noordwijk, The Netherlands William H. Schab Gallery, New York, cat. 40 [1963], no. 64 (the still-intact manuscript), the Meckenem ill. on p. 69 private collection, Switzerland Sotheby’s, London, December 4, 1969, lot 18 William H. Schab Gallery, New York, cat. 52, 1972, no. 46 (ill. in color) C.G. Boerner, Düsseldorf, acquired April 25, 1972 private collection, Germany Sotheby’s, London, December 3–4, 1987, lot 579 (GBP 27,500) private collection Unikum. Very little is known about the early life of Israhel van Meckenem. His family probably came from Meckenheim near Bonn. He might have received his first artistic training with the so- called Master of the Berlin Passion who was active in the Rhine-Meuse region in 1450–70 (and whom Max Geisberg even tried to identify as Van Meckenem’s father). This is supported by 13 copies that Van Meckenem made after prints by this early “Anonymous.” However, the Master E.S. played an even more important role in the formation of the young artist. He worked in the Upper Rhine valley, most likely in Strasbourg, and his importance for the development of the relatively new medium of engraving can hardly be overestimated.